Damselfly

Damselflies are insects of the suborder Zygoptera in the order Odonata. They are similar to dragonflies, which constitute the other odonatan suborder, Anisoptera, but are smaller, have slimmer bodies, and most species fold the wings along the body when at rest, unlike dragonflies which hold the wings flat and away from the body. An ancient group, damselflies have existed since at least the Lower Permian, and are found on every continent except Antarctica.

| Damselfly | |

|---|---|

_male_3.jpg) | |

| Male beautiful demoiselle (Calopteryx virgo) | |

| |

| Female bluetail damselfly (Ischnura heterosticta) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Suborder: | Zygoptera Selys, 1854[1] |

| Families | |

| |

All damselflies are predatory; both nymphs and adults eat other insects. The nymphs are aquatic, with different species living in a variety of freshwater habitats including acid bogs, ponds, lakes and rivers. The nymphs moult repeatedly, at the last moult climbing out of the water to undergo metamorphosis. The skin splits down the back, they emerge and inflate their wings and abdomen to gain their adult form. Their presence on a body of water indicates that it is relatively unpolluted, but their dependence on freshwater makes them vulnerable to damage to their wetland habitats.

Some species of damselfly have elaborate courtship behaviours. Many species are sexually dimorphic, the males often being more brightly coloured than the females. Like dragonflies, they reproduce using indirect insemination and delayed fertilisation. A mating pair form a shape known as a "heart" or "wheel", the male clasping the female at the back of the head, the female curling her abdomen down to pick up sperm from secondary genitalia at the base of the male's abdomen. The pair often remain together with the male still clasping the female while she lays eggs within the tissue of plants in or near water using a robust ovipositor.

Fishing flies that mimic damselfly nymphs are used in wet-fly fishing. Damselflies sometimes provide the subject for personal jewellery such as brooches.

Classification

The Zygoptera are an ancient group, with fossils known from the lower Permian, at least 250 million years ago. All the fossils of that age are of adults, similar in structure to modern damselflies, so it is not known whether their larvae were aquatic at that time. The earliest larval odonate fossils are from the Mesozoic.[2] Fossils of damselfly-like Protozygoptera date back further to 311–30 Mya.[3] Well-preserved Eocene damselfly larvae and exuviae are known from fossils preserved in amber in the Baltic region.[4]

Molecular analysis in 2013 confirms that most of the traditional families are monophyletic, but shows that the Amphipterygidae, Megapodagrionidae and Protoneuridae are paraphyletic and will need to be reorganised. The Protoneuridae in particular is shown to be composed of six clades from five families. The result so far is 27 damselfly families, with 7 more likely to be created. The discovered clades did not agree well with traditional characteristics used to classify living and fossil Zygoptera such as wing venation, so fossil taxa will need to be revisited. The 18 extant traditional families are provisionally rearranged as follows (the 3 paraphyletic families disappearing, and many details not resolved):[5]

| Zygoptera |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dashed lines indicate unresolved relationships.

General description

The general body plan of a damselfly is similar to that of a dragonfly. The compound eyes are large but are more widely separated and relatively smaller than those of a dragonfly. Above the eyes is the frons or forehead, below this the clypeus, and on the upper lip the labrum, an extensible organ used in the capture of prey. The top of the head bears three simple eyes (ocelli), which may measure light intensity, and a tiny pair of antennae that serve no olfactory function but may measure air speed.[6] Many species are sexually dimorphic; the males are often brightly coloured and distinctive, while the females are plainer, cryptically coloured, and harder to identify to species. For example, in Coenagrion, the Eurasian bluets, the males are bright blue with black markings, while the females are usually predominantly green or brown with black.[7] A few dimorphic species show female-limited polymorphism, the females being in two forms, one form distinct and the other with the patterning as in males. The ones that look like males, andromorphs, are usually under a third of the female population but the proportion can rise significantly and a theory that explains this response suggests that it helps overcome harassment by males.[8] Some Coenagrionid damselflies show male-limited polymorphism, an even less understood phenomenon.[9]

In general, damselflies are smaller than dragonflies, the smallest being members of the genus Agriocnemis (wisps).[10] However, members of the Pseudostigmatidae (helicopter damselflies or forest giants) are exceptionally large for the group, with wingspans as much as 19 cm (7.5 in) in Megaloprepus[11] and body length up to 13 cm (5.1 in) in Pseudostigma aberrans.[12]

The first thoracic segment is the prothorax, bearing the front pair of legs. The joint between head and prothorax is slender and flexible, which enables the damselfly to swivel its head and to manoeuvre more freely when flying. The remaining thoracic segments are the fused mesothorax and metathorax (together termed the synthorax), each with a pair of wings and a pair of legs. A dark stripe known as the humeral stripe runs from the base of the front wings to the second pair of legs, and just in front of this is the pale-coloured, antehumeral stripe.[6]

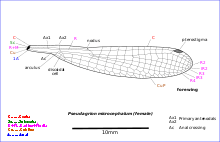

The forewings and hindwings are similar in appearance and are membranous, being strengthened and supported by longitudinal veins that are linked by many cross-veins and that are filled with haemolymph.[13] Species markers include quadrangular markings on the wings known as the pterostigma or stigma, and in almost all species, there is a nodus near the leading edge. The thorax houses the flight muscles.[6] Many damselflies (e.g. Lestidae, Platycnemidae, Coenagrionidae) have clear wings, but some (Calopterygidae, Euphaeidae) have coloured wings, whether uniformly suffused with colour or boldly marked with a coloured patch. In species such as the banded demoiselle, Calopteryx splendens the males have both a darker green body and large dark violet-blue patches on all four wings, which flicker conspicuously in their aerial courtship dances; the females have pale translucent greenish wings.[14]

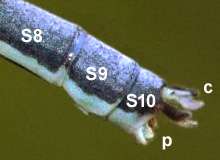

The abdomen is long and slender and consists of ten segments. The secondary genitalia in males are on the undersides of segments two and three and are conspicuous, making it easy to tell the sex of the damselfly when viewed from the side. The female genital opening is on the underside between segments eight and nine. It may be covered by a subgenital plate, or extended into a complex ovipositor that helps them lay eggs within plant tissue. The tenth segment in both sexes bears cerci and in males, its underside bears a pair of paraprocts.[6]

Damselflies (except spreadwings, Lestidae) rest their wings together, above their bodies, whereas dragonflies rest with their wings spread diametrically apart; the spreadwings rest with their wings slightly apart. Damselflies have slenderer bodies than dragonflies, and their eyes do not overlap. Damselfly nymphs differ from dragonflies nymphs in that they possess caudal gills (on the abdomen) whereas dragonflies breathe through the rectum. Damselfly nymphs swim by fish-like undulations, the gills functioning like a tail. Dragonfly nymphs can forcibly expel water in their rectum for rapid escape.[15]

Distribution and diversity

Odonates are found on all the continents except Antarctica.[16] Although some species of dragonfly have wide distributions, damselflies tend to have smaller ranges. Most odonates breed in fresh-water; a few damselflies in the family Caenagrionidae breed in brackish water (and a single dragonfly species breeds in seawater).[17][18] Dragonflies are more affected by pollution than are damselflies. The presence of odonates indicates that an ecosystem is of good quality. The most species-rich environments have a range of suitable microhabitats, providing suitable water bodies for breeding.[19][20]

Although most damselflies live out their lives within a short distance of where they were hatched, some species, and some individuals within species, disperse more widely. Forktails in the family Coenagrionidae seem particularly prone to do this, large male boreal bluets (Enallagma boreale) in British Columbia often migrating, while smaller ones do not.[21] These are known to leave their waterside habitats, flying upwards till lost from view, and presumably being dispersed to far off places by the stronger winds found at high altitudes.[21] In this way they may appear in a locality where no damselflies were to be seen the day before. Rambur's forktail (Ischnura ramburii) has been found, for example, on oil rigs far out in the Gulf of Mexico.[6]

The distribution and diversity of damselfly species in the biogeographical regions is summarized here. (There are no damselflies in the Antarctic.) Note that some species are widespread and occur in multiple regions.[20]

| Family | Oriental | Neotropical | Australasian | Afrotropical | Palaearctic | Nearctic | Pacific | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiphlebiidae | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Lestidae | 40 | 42 | 29 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 3 | 151 |

| Perilestidae | 19 | 19 | ||||||

| Synlestidae | 18 | 1 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 39 | ||

| Platystictidae | 136 | 43 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 224 | ||

| Amphipterygidae | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Argiolestidae | 10 | 73 | 19 | 6 | 108 | |||

| Calopterygidae | 66 | 68 | 5 | 20 | 37 | 8 | 185 | |

| Chlorocyphidae | 86 | 17 | 42 | 3 | 144 | |||

| Devadattidae | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Dicteriadidae | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Euphaeidae | 65 | 1 | 11 | 68 | ||||

| Heteragrionidae | 51 | 51 | ||||||

| Hypolestidae | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Lestoideidae | 9 | 9 | ||||||

| Megapodagrionidae | 29 | 29 | ||||||

| Pentaphlebiidae | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Philogangidae | 4 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Philogeniidae | 39 | 39 | ||||||

| Philosinidae | 12 | 12 | ||||||

| Polythoridae | 59 | 59 | ||||||

| Pseudolestidae | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Rimanellidae | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Thaumatoneuridae | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Incertae sedis | 25 | 11 | 19 | 9 | 61 | |||

| Coenagrionidae | 193 | 554 | 152 | 202 | 96 | 103 | 91 | 1266 |

| Isostictidae | 41 | 46 | ||||||

| Platycnemididae | 199 | 122 | 70 | 22 | 404 | |||

Overall, there are about 2942 extant species of damselflies placed in 309 genera.[20]

Biology

Adult damselflies catch and eat flies, mosquitoes, and other small insects. Often they hover among grasses and low vegetation, picking prey off stems and leaves with their spiny legs.[21] Although predominantly using vision to locate their prey, adults may also make use of olfactory cues.[22] No species are known to hunt at night, but some are crepuscular, perhaps taking advantage of newly hatched flies and other aquatic insects at a time when larger dragonflies are roosting.[23] In tropical South America, helicopter damselflies (Pseudostigmatidae) feed on spiders, hovering near an orb web and plucking the spider, or its entangled prey, from the web.[24] There are few pools and lakes in these habitats, and these damselflies breed in temporary water bodies in holes in trees, the rosettes of bromeliads and even the hollow stems of bamboos.[25]

The nymphs of damselflies have been less researched than their dragonfly counterparts, and many have not even been identified. They choose their prey according to size and seem less able to overpower larger prey than can dragonfly nymphs. The major part of the diet of most species appears to be crustaceans such as water fleas.[23]

Ecology

Damselflies exist in a range of habitats in and around the wetlands needed for their larval development; these include open spaces for finding mates, suitable perches, open aspect, roosting sites, suitable plant species for ovipositing and suitable water quality, and odontates have been used for bio-indication purposes regarding the quality of the ecosystem. Different species have different requirements for their larvae with regard to water depth, water movement and pH.[26] The European common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum) for example can occur at high densities in acid waters where fish are absent, such as in bog pools.[27] The scarce blue-tailed damselfly (Ischnura pumilio) in contrast requires base-rich habitats and water with a slow flow-rate. It is found in ditches, quarries, seeps, flushes, marshes and pools. It tolerates high levels of zinc and copper in the sediment but requires suitable emergent plants for egg-laying without the water being choked by plants.[26] Damselflies' dependence on freshwater habitats makes them very vulnerable to damage to wetlands through drainage for agriculture or urban growth.[28]

In the tropics, the helicopter damselfly Mecistogaster modesta (Pseudostigmatidae) breeds in phytotelmata, the small bodies of water trapped by bromeliads, epiphytic plants of the rainforest of northwest Costa Rica, at the high density of some 6000 larvae per hectare in patches of secondary forest.[29] Another tropical species, the cascade damselfly Thaumatoneura inopinata (Megapodagrionidae), inhabits waterfalls in Costa Rica and Panama.[30][31]

Damselflies, both nymphs and adults, are eaten by a range of predators including birds, fish, frogs, dragonflies, other damselflies, water spiders, water beetles, backswimmers and giant water bugs.[21]

Damselflies have a variety of internal and external parasites. Particularly prevalent are the gregarine protozoans found in the gut. In a study of the European common blue damselfly, every adult insect was infected at the height of the flying season. When present in large numbers, these parasites can cause death by blocking the gut.[21] Bright red water mites Hydracarina are often seen on the outside of both nymphs and adults, and can move from one to the other at metamorphosis.[21] They suck the body fluids and may actually kill young nymphs, but adults are relatively unaffected, it being necessary for the completion of the mite's life cycle that it returns to water, a feat accomplished when the adult damselfly breeds.[32]

Behaviour

_(14681891387).jpg)

Many damselflies have elaborate courtship behaviours. These are designed to show off the male's distinctive characteristics, bright colouring or flying abilities, thus demonstrating his fitness. Calopteryx males will hover in front of a female with alternating fast and slow wingbeats; if she is receptive she will remain perched, otherwise she will fly off. The male river jewelwing (Calopteryx aequabilis) performs display flights in front of the female, fluttering his forewings while keeping his hindwings still, and raising his abdomen to reveal the white spots on his wings.[33] Platycypha males will hover in front of a female, thrusting their bright white legs forward in front of their heads. Rhinocypha will bob up and down, often low over fast-flowing streams, displaying their bright-coloured bodies and wings. Male members of the family Protoneuridae with vividly coloured wings display these to visiting females.[34] Swift forktail (Ischnura erratica) males display to each other with their blue-tipped abdomens raised.[35]

Other behaviours observed in damselflies include wing-warning, wing-clapping, flights of attrition and abdominal bobbing. Wing-warning is a rapid opening and closing of the wings and is aggressive, while wing-clapping involves a slower opening of the wings followed by a rapid closure, up to eight times in quick succession, and often follows flight; it may serve a thermo-regulatory function.[36] Flights of attrition are engaged in by the ebony jewelwing (Calopteryx maculata) and involve males bouncing around each other while flying laterally and continuing to do so, sometimes over a considerable distance, until one insect is presumably exhausted and gives up.[37]

At night, damselflies usually roost in dense vegetation, perching with the abdomen alongside a stem. If disturbed they will move around to the other side of the stem but will not fly off. Spreadwings fully fold their wings when roosting.[6] The desert shadowdamsel (Palaemnema domina) aggregates to roost in thick places near streams in the heat of the day. While there it engages in wing-clapping, the exact function of which is unknown.[38] Some species such as the rubyspot damselfly, Hetairina americana, form night roosting aggregations, with a preponderance of males; this may have an anti-predator function or may be simply the outcome of choosing safe roosting sites.[39]

Reproduction

Mating in damselflies, as in dragonflies, is a complex, precisely choreographed process involving both indirect insemination and delayed fertilisation.[40][41] The male first has to attract a female to his territory, continually driving off rival males. When he is ready to mate, he transfers a packet of sperm from his primary genital opening on segment 9, near the end of his abdomen, to his secondary genitalia on segments 2–3, near the base of his abdomen. The male then grasps the female by the head with the claspers at the end of his abdomen; the structure of the claspers varies between species, and may help to prevent interspecific mating.[41][42] The pair fly in tandem with the male in front, typically perching on a twig or plant stem. The female then curls her abdomen downwards and forwards under her body to pick up the sperm from the male's secondary genitalia, while the male uses his "tail" claspers to grip the female behind the head: this distinctive posture is called the "heart" or "wheel";[40][43] the pair may also be described as being "in cop".[44] Males may transfer the sperm to their secondary genitalia either before a female is held, in the early stage when the female is held by the legs or after the female is held between the terminal claspers. This can lead to variations in the tandem postures.[45] The spermatophore may also have nutrition in addition to sperms as a "nuptial gift".[46] Some cases of sexual cannibalism exist where females (of Ischnura graellsii) eat males while in copula.[47]

Parthenogenesis (reproduction from unfertilised eggs) is exceptional, and has only been recorded in nature in female Ischnura hastata on the Azores Islands.[20][48]

Egg-laying (ovipositing) involves not only the female darting over floating or waterside vegetation to deposit eggs on a suitable substrate, but the male hovering above her, mate-guarding, or in some species continuing to clasp her and flying in tandem. The male attempts to prevent rivals from removing his sperm and inserting their own,[49] a form of sperm competition (the sperms of the last mated male have the greatest chance of fertilizing the eggs, also known as sperm precedence[50]) made possible by delayed fertilisation[40][43] and driven by sexual selection.[41][42] If successful, a rival male uses his penis to compress or scrape out the sperm inserted previously; this activity takes up much of the time that a copulating pair remain in the heart posture.[44] Flying in tandem has the advantage that less effort is needed by the female for flight and more can be expended on egg-laying, and when the female submerges to deposit eggs, the male may help to pull her out of the water.[49]

All damselflies lay their eggs inside plant tissues; those that lay eggs underwater may submerge themselves for 30 minutes at a time, climbing along the stems of aquatic plants and laying eggs at intervals.[51] For example, the red-eyed damselfly Erythromma najas lays eggs, in tandem, into leaves or stems of floating or sometimes emergent plants; in contrast, the scarce bluetail Ischnura pumilio oviposits alone, the female choosing mostly emergent grasses and rushes, and laying her eggs in their stems either above or just below the waterline.[52] The willow emerald Chalcolestes viridis (a spreadwing) is unusual in laying eggs only in woody plant tissue, choosing thin twigs of trees that hang over water, and scarring the bark in the process.[53] A possible exception is an apparent instance of ovo-viviparity, in which Heliocypha perforata was filmed in western China depositing young larvae (presumably hatched from eggs inside the female's body) onto a partly submerged branch of a tree.[54]

Many damselflies are able to produce more than one brood per year (voltinism); this is negatively correlated with latitude, becoming more common towards the equator, except in the Lestidae.[55]

Life cycle

Damselflies are hemimetabolous insects that have no pupal stage in their development.[56] The female inserts the eggs by means of her ovipositor into slits made in water plants or other underwater substrates and the larvae, known as naiads or nymphs, are almost all completely aquatic.[6] Exceptions include the Hawaiian Mealagrion oahuense and an unidentified Megapodagrionid from New Caledonia,[57] which are terrestrial in their early stages.[49] The spreadwings lay eggs above the waterline late in the year and the eggs overwinter, often covered by snow. In spring they hatch out in the meltwater pools and the nymphs complete their development before these temporary pools dry up.[21]

_nymph.jpg)

The nymphs are voracious predators and feed by means of a flat labium (a toothed mouthpart on the lower jaw) that forms the so-called mask; it is rapidly extended to seize and pierce the Daphnia (water fleas), mosquito larvae, and other small aquatic organisms on which damselfly nymphs feed. They breathe by means of three large external, fin-like gills on the tip of the abdomen, and these may also serve for locomotion in the same manner as a fish's tail.[6] Compared to dragonfly larvae, the nymphs show little variation in form. They tend to be slender and elongate, many having morphological adaptations for holding their position in fast flowing water. They are more sensitive than dragonfly nymphs to oxygen levels and suspended fine particulate matter, and do not bury themselves in the mud.[23]

The nymphs proceed through about a dozen moults as they grow. In the later stages, the wing pads become visible. When fully developed, the nymphs climb out of the water and take up a firm stance, the skin on the thorax splits and the adult form wriggles out. This has a soft body at first and hangs or stands on its empty larval case. It pumps haemolymph into its small limp wings, which expand to their full extent. The haemolymph is then pumped back into the abdomen, which also expands fully. The exoskeleton hardens and the colours become more vivid over the course of the next few days. Most damselflies emerge in daytime and in cool conditions the process takes several hours. On a hot day, the cuticle hardens rapidly and the adult can be flying away within half an hour.[6]

Conservation

Conservation of Odonata has usually concentrated on the more iconic suborder Anisoptera, the dragonflies. However, the two suborders largely have the same needs, and what is good for dragonflies is also good for damselflies. The main threats experienced by odonates are the clearance of forests, the pollution of waterways, the lowering of groundwater levels, the damming of rivers for hydroelectric schemes and the general degradation of wetlands and marshes.[58] The clearance of tropical rainforests is of importance because the rate of erosion increases, streams and pools dry up and waterways become clogged with silt. The presence of alien species can also have unintended consequences.[58] In Hawaii, the introduction of the mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) was effective in controlling mosquitoes but nearly exterminated the island's endemic damselflies.[59] The ancient greenling Hemiphlebia mirabilis has been an important flagship species for conservation action in preserving its habitat in Australia.[60]

In culture

Damselfly is a 2005 short film directed by Ben O'Connor.[61] Damselfly is also the title of a 2012 novel in the Faeble series by S. L. Naeole,[62] and of a 1994 poem by August Kleinzahler, which contains the lines "And that blue there, cobalt / a moment, then iridescent, / fragile as a lady's pin / hovering above the nasturtium?"[63] The poet John Engels published Damselfly, Trout, Heron in his 1983 collection Weather-Fear: New and Selected Poems.[64]

Fishing flies that mimic damselfly nymphs are sometimes used in wet-fly fishing, where the hook and line are allowed to sink below the surface.[65]

Damselflies have formed subjects for personal jewellery such as brooches since at least 1880.[66]

References

- Selys-Longchamps, E. (1854). Monographie des caloptérygines (in French). Brussels and Leipzig: C. Muquardt. pp. 1–291 [2]. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60461. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107312183.

- Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 174, 178. ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0.

- Jarzembowski, E. A.; A. Nel (2002). "The earliest damselfly like insect and the origin of modern dragonflies (Insecta: Odonatoptera: Protozygoptera)". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 113 (2): 165–169. doi:10.1016/s0016-7878(02)80018-9.

- Bechly, Günter; Wichard, Wilfried (30 December 2008). "Damselfly and dragonfly nymphs in Eocene Baltic amber (Insecta: Odonata), with aspects of their palaeobiology" (PDF). Palaeodiversity. 1: 37–73.

- Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe B.; Kalkman, Vincent J.; Dow, Rory A.; Stokvis, Frank R.; van Tol, Jan (2013). "Redefining the damselfly families: a comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Zygoptera (Odonata)". Systematic Entomology. 39 (1): 68–96. doi:10.1111/syen.12035.

- Paulson, Dennis (2011). Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton University Press. pp. 10–32. ISBN 978-1-4008-3966-7.

- Dijkstra 2006, pp. 20, 104.

- Gossum, Hans Van; Sherratt, Thomas N. (2008). "A dynamical model of sexual harassment in damselflies and its implications for female-limited polymorphism". Ecological Modelling. 210 (1–2): 212–220. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.07.023.

- Gossum, Hans Van; Sherratt, Tom N.; Cordero-Rivera, Adolfo (2008). "The evolution of sex-limited colour polymorphism". In Cordoba-Aguilar, Alex (ed.). Dragonflies and Damselflies. Model organisms for ecological and evolutionary research. Oxford University Press. pp. 219–229. ISBN 9780199230693.

- Kipping, Jens; Martens, Andreas; Suhling, Frank (2012). "Africa's smallest damselfly – a new Agriocnemis from Namibia". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 12 (3): 301–306. doi:10.1007/s13127-012-0084-4.

- Groenevelda, Linn F.; Viola Clausnitzerb; Heike Hadrysa (2007). "Convergent Evolution of Gigantism in Damselflies of Africa and South America? Evidence from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Sequence Data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 42 (2): 339–46. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.040. PMID 16945555.

- Hedström, Ingemar; Göran Sahlén (2001). "A key to the adult Costa Rican "helicopter" damselflies (Odonata: Pseudostigmatidae) with notes on their phenology and life zone preferences". Rev. Biol. Trop. 49 (3–4): 1037–1056. PMID 12189786.

- Silsby, Jill (2001). Dragonflies of the World. Csiro Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-643-10249-1.

- Dijkstra 2006, pp. 23, 65–67.

- Borror, Donald J.; Triplehorn, Charles A.; Triplehorn, Norman F. Study of Insects (6 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 187–201.

- Nilsson, Anders (1997). Aquatic insects of North Europe: A taxonomic handbook. Apollo Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-87-88757-07-1.

- Osburn, Raymond C. (1906). "Observations and Experiments on Dragon-Flies in Brackish Water". The American Naturalist. 40 (474): 395–399. doi:10.1086/278632.

- Dunson, William A. (1980). "Adaptations of Nymphs of a Marine Dragonfly, Erythrodiplax berenice, to Wide Variations in Salinity". Physiological Zoology. 53 (4): 445–452. doi:10.1086/physzool.53.4.30157882.

- "Introduction to the Odonata". UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Suhling, F.; Sahlén, G.; Gorb, S.; Kalkman, V.J.; Dijkstra, K-D.B.; van Tol, J. (2015). "Order Odonata". In Thorp, James; D. Christopher Rogers (eds.). Ecology and general biology. Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates (4 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 893–932. ISBN 978-0-12-385026-3.

- Acorn, John (2004). Damselflies of Alberta: Flying Neon Toothpicks in the Grass. University of Alberta. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-0-88864-419-0.

- Piersanti, Silvana; Frati, Francesca; Conti, Eric; Gaino, Elda; Rebora, Manuela; Salerno, Gianandrea (2014). "First evidence of the use of olfaction in Odonata behaviour". Journal of Insect Physiology. 62: 26–31. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.01.006. PMID 24486162.

- Heckman, Charles W. (2008). Encyclopedia of South American Aquatic Insects: Odonata - Zygoptera: Illustrated Keys to Known Families, Genera, and Species in South America. Springer. pp. 17, 31–33. ISBN 978-1-4020-8176-7.

- Ingley, Spencer J.; Bybee, Seth M.; Tennessen, Kenneth J.; Whiting, Michael F.; Branham, Marc A. (2012). "Life on the fly: phylogenetics and evolution of the helicopter damselflies (Odonata, Pseudostigmatidae)". Zoologica Scripta. 41 (6): 637–650. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00555.x.

- Fincke, Ola M. (2006). "Use of Forest and Tree Species, and Dispersal by Giant Damselflies (Pseudostigmatidae): Their Prospects in Fragmented Forests" (PDF). In Adolfo Cordero Rivera (ed.). Fourth WDA International Symposium of Odonatology, Pontevedra (Spain), July 2005. Sofia—Moscow: Pensoft Publishers. pp. 103–125. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-28.

- Allen, Katherine (2009). The ecology and conservation of threatened damselflies. The Environment Agency. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-1-84911-093-8.

- Dijkstra 2006, p. 102.

- Corbet, P. S. (1980). "Biology of Odonata". Annual Review of Entomology. 25: 189–217. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.001201.

- Srivastava, Diane S.; Melnychuk, Michael C.; Ngai, Jacqueline T. (2005). "Landscape variation in the larval density of a bromeliad-dwelling zygopteran, Mecistogaster modesta (Odonata: Pseudostigmatidae)". International Journal of Odonatology. 8 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1080/13887890.2005.9748244. S2CID 53603745.

- Calvert, Philip P. (1914). "Studies on Costa Rican Odonata. V. The waterfall-dwellers: Thaumatoneura imagos and possible male dimorphism". Entomological News and Proceedings of the Entomological Section. 25 (8): 337–348.

- "Thaumatoneura inopinata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Proctor, Heather (2004). Aquatic Mites from Genes to Communities: From Genes to Communities. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-1-4020-2703-1.

- Paulson 2009, p. 42.

- Silsby, Jill (2001). Dragonflies of the World. Csiro Publishing. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-643-10249-1.

- Paulson 2009, p. 108.

- Bick, George H.; Bick, Juanda C. (1961). "Demography and Behavior of the Damselfly, Argia Apicalis (Say), (Odonata: Coenagriidae)". Ecology. 46 (4): 461–472. doi:10.2307/1934877. JSTOR 1934877.

- Paulson 2009, p. 44.

- Paulson 2009, p. 185.

- Switzer, Paul V.; Grether, Gregory F. (2000). "Characteristics and Possible Functions of Traditional Night Roosting Aggregations in Rubyspot Damselflies" (PDF). Behaviour. 137 (4): 401–416. doi:10.1163/156853900502141.

- Dijkstra 2006, pp. 8–9.

- Battin, Tom (1993). "The odonate mating system, communication, and sexual selection: A review". Bolletino di Zoologia. 60 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1080/11250009309355839.

- Cordero-Rivera, Adolfo; Cordoba-Aguilar, Alex (2010). "Selective Forces Propelling Genitalic Evolution in Odonata" (PDF). In Leonard, Janet; Alex Córdoba-Aguilar (eds.). The Evolution of Primary Sexual Characters in Animals. Oxford University Press. p. 343.

- Trueman & Rowe 2009, p. Life Cycle and Behavior.

- Berger 2004, p. 39.

- Bick, G. H.; Bick, J. C. (1965). "Sperm Transfer in Damselflies (Odonata: Zygoptera)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 58 (4): 592. doi:10.1093/aesa/58.4.592. PMID 5834678.

- Cordero Rivera, A; Cordoba-Aguilar, A (2010). "Selective forces propelling genitalic evolution in Odonata". In Leonard J; Cordoba-Aguilar, A (eds.). The evolution of primary characters in animals. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 332–352.

- Cordero, Adolfo (1992). "Sexual Cannibalism in the Damselfly Species Ischnura graellsii (Odonata: Coenagrionidae)" (PDF). Entomologia Generalis. 17 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1127/entom.gen/17/1992/17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- Lorenzo-Carballa, M. O.; Cordero-Rivera, A. (2009). "Thelytokous parthenogenesis in the damselfly Ischnura hastata (Odonata, Coenagrionidae): genetic mechanisms and lack of bacterial infection". Heredity. 103 (5): 377–384. doi:10.1038/hdy.2009.65. PMID 19513091.

- Cardé, Ring T.; Resh, Vincent H. (2012). A World of Insects: The Harvard University Press Reader. Harvard University Press. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-674-04619-1.

- Tennessen, K.J. (2009). "Odonata (Dragonflies, Damselflies)". In Resh, Vincent H.; Ring T. Cardé (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects (2 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 721–729.

- Lawlor, Elizabeth P. (1999). Discover Nature in Water & Wetlands: Things to Know and Things to Do. Stackpole Books. pp. 88, 94–96. ISBN 978-0-8117-2731-0.

- Smallshire, Dave; Swash, Andy (2014). Britain's Dragonflies: A Field Guide to the Damselflies and Dragonflies of Britain and Ireland: A Field Guide to the Damselflies and Dragonflies of Britain and Ireland. Princeton University Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1-4008-5186-7.

- Dijkstra 2006, p. 84.

- Salindra, H. G.; Dayananda, K.; Kitching, Roger L. (2014). "Ovo-viviparity in the Odonata? The case of Heliocypha perforata (Zygoptera: Chlorocyphidae)". International Journal of Odonatology. 17 (4): 181–185. doi:10.1080/13887890.2014.959076.

- Corbet, Philip S.; Suhling, Frank; Soendgerath, Dagmar (2006). "Voltinism of Odonata: a review". International Journal of Odonatology. 9 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1080/13887890.2006.9748261.

- A Dictionary of Entomology. CABI. 2011. p. 679. ISBN 978-1-84593-542-9.

- Willey, Ruth Lippitt (1955). "A terrestrial damselfly nymph (Medapodarionidae) from New Caledonia" (PDF). Psyche. 62 (4): 137–144. doi:10.1155/1955/39831.

- Moore, N.W. (1997). "Dragonflies: status survey and conservation action plan" (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Gagné, W.C. (1981). "Status of Hawaii endangered species: insects and land snails". 'Elepaio. 42: 31–36.

- New, Timothy Richard. "The Hemiphlebia damselfly Hemiphlebia mirabilis Selys (Odonata, Zygoptera) as a flagship species for aquatic insect conservation in south-eastern Australia". The Victorian Naturalist. 124 (4): 269–272.

- "Ben O'Connor". British Council. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Naeole, S. L. (2012). Damselfly. Crystal Quill.

- Kleinzahler, August (August 1994). "The Damselfly". Poetry Magazine. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Engels, John (1983). Damselfly, Trout, Heron. Weather-Fear: New and Selected Poems. University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Wada, Wes (2012). "Fishing Tips for the Juicebug Damsel Nymph". Fly foundry. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Antique "Damselfly" Brooch in Silver-topped Gold with Ruby Eyes". Macklowe Gallery. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zygoptera. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Zygoptera |

- Berger, Cynthia (2004). Dragonflies. Stackpole Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8117-2971-0.

- Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe B. (2006). Field Guide to the Dragonflies of Britain and Europe. British Wildlife Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9531399-4-1.

- Paulson, Dennis (2009). Dragonflies and Damselflies of the West. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3294-1.

- Trueman, John W. H.; Rowe, Richard J. (2009). "Odonata". Tree of Life. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

External links

| Look up damselfly in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Tree of Life: Odonata

- Dragonflies and damselflies on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Minnesota Dragonfly Society: Biology and Ecology