Arthropods in film

Arthropods, mainly insects and arachnids, are used in film either to create fear and disgust in horror and thriller movies, or they are anthropomorphized and used as sympathetic characters in animated children's movies. There are over 1,000,000 species of arthropods, including such familiar animals as ants, spiders, shrimps, crabs and butterflies.

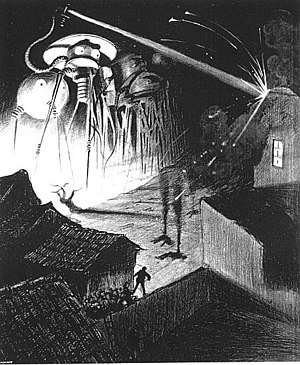

Early 20th century films had difficulty featuring small insects due to technical difficulties in film-stock exposure and the quality of lenses available.[1] Horror movies involving arthropods include the pioneering 1954 Them!, featuring giant ants mutated by radiation, and the 1957 The Deadly Mantis. Films based on oversized arthropods are sometimes described as big bug movies.[2][3][4][5]

Arthropods used in films may be animated, sculpted, or otherwise synthesized; however, in many cases these films use actual creatures. As these creatures are not easily tamed or directed, a specialist known as a "Bug Wrangler" may be hired to control and direct these creatures. Some bug wranglers have become famous as a result of their expertise, such as Norman Gary, a champion bee-wrangler who is also a college professor, and Steven R. Kutcher, who wrangles a multitude of different types of bugs and who is the subject of over 100 print articles.[1]

Horror

Arthropods are effective tools to instill horror, because fear of arthropods may be conditioned into people's minds. Indeed, Jamie Whitten quoted in his book That We May Live, (talking about insects):

The enemy is already here-in the skies, in the fields, and waterways. It is dug into every square foot of our earth; it has invaded homes, schoolhouses, public buildings; it has poisoned food and water; it brings sickness and death by germ warfare to countless millions of people every year.... The enemy within-these walking, crawling, jumping, flying pests-destroy more crops than drought and floods. They destroy more buildings than fire. They are responsible for many of the most dreaded diseases of man and his domestic animals.... Some of them eat or attack everything man owns or produces-including man himself.[6]

Thus, insects and other arthropods are dangerous to humans in both obvious and less obvious ways. Undoubtedly, arthropods are dangerous for their potential to carry disease. Somewhat less apparently, arthropods cause damage to buildings, crops, and animals. Since arthropods can be harmful in so many ways, using insects and other arthropods to frighten people in movies was a logical step.

Aside from a natural fear or aversion to arthropods, reasons for using such creatures in movies could be metaphorical. Many of the most famous "Big Bug Movies" were made in the 1950s in the aftermath of World War II, when the world was introduced to the cataclysmic destruction inflicted by nuclear bombs. The bomb was unapproachable, remote, and terrifying; spiders and ants mutated by nuclear radiation to become huge were terrifying, but thanks to the competent government officials, soldiers, policemen, and detectives, the bugs were stopped and safety was restored. Nuclear terror was conquered without expressly facing a nuclear bomb. In this way, big bug movies could be cathartic and liberating to the general public.[7]

Big bug films may symbolize sexual desire. Margaret Tarrat says in her article "Monsters of the id" that "[Big bug movies] arrive at social comment through a dramatization of the individual's anxiety about his or her own repressed sexual desires, which are incompatible with the morals of civilized life."[8] By this theory, gigantic swarming insects could represent the huge, torrential—but repressed due to the demands of society—sexual desires possessed by the creator and viewer of the Big Bug movie.

On gigantic arthropods, Charles Q. Choi stated that, if the atmosphere had a higher percentage of oxygen, arthropods would be able to grow quite a bit larger before their trachea became too large and could not grow any more. In fact, in the early years of the earth, when the atmosphere was more oxygen-rich, dragonflies the size of crows were not an uncommon sight.[9]

Animation

Winsor McCay, one of the founders of animation, made the first animated film about insects in 1912, titled How a Mosquito Operates. In the early 20th century, it was technically easier to include insects in animated films, which are drawn, over live-action films which would require more advanced techniques to film insects, due to their small size, necessitating better lenses and exposure techniques than those available at the time. One filmmaker, Władysław Starewicz, found that when filming live stag beetles, they tended to stop moving under the hot lights. To solve this problem, he killed his film subjects and attached wires to their bodies in order to puppeteer them. His films were successful, and he eventually abandoned real insects in favor of puppets of his own creation. One of the best-known animated insects is Jiminy Cricket, whose initial design was more realistic and insect-like, but eventually evolved into an elf-like creature. Computer-animated films have proven particularly suited for depicting insects, beginning with Pixar's 1984 short film The Adventures of André and Wally B. Early computer animation was successful at depicting rod-like appendages and shiny metallic surfaces, lending itself to the depiction of insects. By 1996, films like Joe’s Apartment achieved rendering hundreds of photorealistic insects. Other animated films continued to depict more anthropomorphized characters, such as A Bug's Life and Antz, both of which came out in 1998, and the 2007 Bee Movie.[1][10]

One reason insects are used successfully in such animations could be that an insect or other arthropod's small size makes it seem heroic and sympathetic when faced against the big, big world. Another reason is counterpoint to the reason for using arthropods in horror films: whereas horror movies play upon the instinctive negative reaction humans have towards insects and arachnids, these animation films make something that is different and strange seem real, approachable, and sympathetic, thus making it comforting.[11]

References

- Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (2009), Encyclopedia of Insects, Academic Press, pp. 668–674, ISBN 978-0-080-92090-0

- Tsutsui, William M. (April 2007). "Looking Straight at "Them!" Understanding the Big Bug Movies of the 1950s". Environmental History. 12 (2): 237–253. JSTOR 25473065.

- Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-137-49639-3.

- Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4766-2505-8.

- Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen. ECW Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-55490-330-6.

- Belveal, Dee, Today's Health, Feb. 1996. Quoted in Whitten, Jamie L. That We May Live," D. Van Norstrand Company 1996. Print.

- Tsutsui, William M. (2007). "Looking Straight at Them! Understanding the Big Bug Movies of the 1950s". Environmental History. 12 (2): 237–253. doi:10.1093/envhis/12.2.237.

- Margaret Tarratt, "Monsters from the Id" (1970), in Film Genre Reader, ed. Barry Keith Grant (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 259.

- Choi, Charles Q., LiveScience, 11 Oct. 2006, "Giant Insects", 8 Dec. 2010.

- Scott, A. O. (2 November 2007). "A Drone No More: No Hive for Him!". The New York Times.

- Leskosky, R.J. and M.R. Berenbaum. "Insects in Animated Films: Not All 'Bugs' are Bunnies." Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America. 1988. 34: pp.55-63.

Further reading

- Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (2009). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 668—674. ISBN 9780080920900.

- Berenbaum, May R. (2010). Bugs in the System: Insects and Their Impact on Human Affairs. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781459608108.