Prospecting

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (second – exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals or mineral specimens, and is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting relied on direct observation of mineralization in rock outcrops or in sediments. Modern prospecting also includes the use of geologic, geophysical, and geochemical tools to search for anomalies which can narrow the search area. Once an anomaly has been identified and interpreted to be a potential prospect direct observation can then be focused on this area.[1]

In some areas a prospector must also make claims, meaning they must erect posts with the appropriate placards on all four corners of a desired land they wish to prospect and register this claim before they may take samples. In other areas publicly held lands are open to prospecting without staking a mining claim.

Historical methods

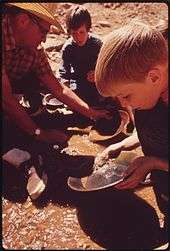

The traditional methods of prospecting involved combing through the countryside, often through creek beds and along ridgelines and hilltops, often on hands and knees looking for signs of mineralisation in the outcrop. In the case of gold, all streams in an area would be panned at the appropriate trap sites looking for a show of 'colour' or gold in the river trail.

Once a small occurrence or show was found, it was then necessary to intensively work the area with pick and shovel, and often via the addition of some simple machinery such as a sluice box, races and winnows, to work the loose soil and rock looking for the appropriate materials (in this case, gold). For most base metal shows, the rock would have been mined by hand and crushed on site, the ore separated from the gangue by hand.

Often, these shows were short-lived, exhausted and abandoned quite soon, requiring the prospector to move onwards to the next and hopefully bigger and better show. Occasionally, though, the prospector would strike it rich and be joined by other prospectors and larger-scale mining would take place. Although these are thought of as "old" prospecting methods, these techniques are still used today but usually coupled with more advanced techniques such as geophysical magnetic or gravity surveys.

In most countries in the 19th and early 20th century, it was very unlikely that a prospector would retire rich even if he was the one who found the greatest of lodes. For instance Patrick (Paddy) Hannan, who discovered the Golden Mile, Kalgoorlie, died without receiving anywhere near a fraction of the value of the gold contained in the lodes. The same story repeated at Bendigo, Ballarat, Klondike and California.

The gold rushes

In the United States and Canada prospectors were lured by the promise of gold, silver, and other precious metals. They traveled across the mountains of the American West, carrying picks, shovels and gold pans. The majority of early prospectors had no training and relied mainly on luck to discover deposits.

Other gold rushes occurred in Papua New Guinea, Australia at least four times, and in South Africa and South America. In all cases, the gold rush was sparked by idle prospecting for gold and minerals which, when the prospector was successful, generated 'gold fever' and saw a wave of prospectors comb the countryside.

Modern Prospecting

Modern prospectors today rely on training, the study of geology, and prospecting technology.

Knowledge of previous prospecting in an area helps in determining location of new prospective areas. Prospecting includes geological mapping, rock assay analysis, and sometimes the intuition of the prospector.

Metal detecting

Metal detectors are invaluable for gold prospectors, as they are quite effective at detecting gold nuggets within the soil down to around 1 metre (3 feet), depending on the acuity of the operator's hearing and skill.

Magnetic separators may be useful in separating the magnetic fraction of a heavy mineral sand from the nonmagnetic fraction, which may assist in the panning or sieving of gold from the soil or stream.

Prospecting pickaxe

Prospecting pickaxes are used to scrape at rocks and minerals, obtaining small samples that can be tested for trace amounts of ore. Modern prospecting pickaxes are also sometimes equipped with magnets, to aid in the gathering of ferromagnetic ores. Prospecting pickaxes are usually equipped with a triangular head, with a very sharp point.

Electromagnetic Prospecting

The introduction of modern gravity and magnetic surveying methods has greatly facilitated the prospecting process. Airborne gravimeters and magnetometers can collect data from vast areas and highlight anomalous geologic features.[2] Three-dimensional inversions of audio-magnetotellurics (AMT) is used to find conductive materials up to a few kilometres into the Earth, which has been helpful to locate kimberlite pipes, as well as tungsten and copper.[3][4]

Another relatively new prospecting technique is using low frequency electromagnetic (EM) waves for 'sounding' into the Earth's crust. These low frequency waves will respond differently based on the material they pass through, allowing for analysts to create three-dimensional images of potential ore bodies or volcanic intrusions. This technique is used for a variety of prospecting, but can mainly be for finding conductive materials.[5] So far these low frequency EM techniques have been proven for geothermal exploration as well as for coal bed methane analysis.[6][7]

Geochemical Prospecting

Geochemical prospecting involves analyzing the chemical properties of rock samples, drainage sediments, soils, surface and ground waters, mineral separates, atmospheric gases and particulates, and even plants and animals. Properties such as trace element abundances are analyzed systematically to locate anomalies.[8]

See also

- Bioprospecting

- Geobotanical prospecting

- Gold prospecting

- Gold Prospectors Association of America

- Gold rush

- Mineral exploration

- Mining

- Oil exploration

- United States Geological Survey

- Metal Detector

References

- "Mining - Prospecting and exploration". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- Dobrin, Milton B. (1960). Introduction to Geophysical Prospecting.

- Farquharson, Colin; Craven, James (August 2009). "Three-dimensional inversion of magnetotelluric data for mineral exploration: An example from the McArthur River uranium deposit, Saskatchewan, Canada". Journal of Applied Geophysics. 68 (4): 450–458. Bibcode:2009JAG....68..450F. doi:10.1016/j.jappgeo.2008.02.002.

- Shi, Yuan (January 2020). "Three-dimensional audio-frequency magnetotelluric imaging of Zhuxi copper-tungsten polymetallic deposits, South China". Journal of Applied Geophysics. 172: 103910. Bibcode:2020JAG...17203910S. doi:10.1016/j.jappgeo.2019.103910.

- Singh, Anand; Sharma, S.P. (2015). "Fast imaging of subsurface conductors using very low-frequency electromagnetic data". Geophysical Prospecting. 63 (6).

- Wang, Nan (2017). "Passive super-low frequency electromagnetic prospecting technique". Frontiers of Earth Science. 11: 248–267.

- Van Der Kruk, J (2002). "An apparent-resistivity concept for low-frequency electromagnetic sounding techniques". Geophysical Prospecting. 48 (6).

- Fletcher, W.K. Analytical Methods in Geochemical Prospecting.