Clarified butter

Clarified butter is milk fat rendered from butter to separate the milk solids and water from the butterfat.[1] Typically, it is produced by melting butter and allowing the components to separate by density. The water evaporates, some solids float to the surface and are skimmed off, and the remainder of the milk solids sink to the bottom and are left behind when the butterfat (which would then be on top) is poured off or separated with a separatory funnel or a gravy fat separator. This butterfat is the clarified butter.

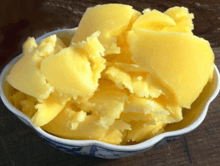

Freshly made clarified butter, still liquid | |

| Alternative names | Ghee; Samneh |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | worldwide distribution |

| Main ingredients | butter, sorghum flour, wood from grapevine (for added smoked flavor) |

Commercial methods of production also include direct evaporation, but may also be accomplished by decantation and centrifugation followed by vacuum drying; or direct from cream by breaking the emulsion followed by centrifugation.[2]

Properties

Clarified butter has a higher smoke point (252 °C or 486 °F) than regular butter (163–190 °C or 325–374 °F),[3] and is therefore preferred in some cooking applications, such as sautéing. Clarified butter also has a much longer shelf life than fresh butter. It has negligible amounts of lactose and casein and is, therefore, acceptable to most who have a lactose intolerance or milk allergy.

Regional variations

In South Asian cuisine ghee is made by cooking clarified butter longer during the separation process in order to caramelize the milk solids, resulting in a nutty flavor when they are filtered out.[4][5][6][7]

See also

- Ghee, a class of clarified butter that originated from the Indian subcontinent

- Manteiga-da-terra, a Brazilian clarified butter product

- Niter kibbeh, a seasoned, clarified butter used in Ethiopian cuisine

- Smen, a salted, fermented clarified butter, widely used in North African and Middle Eastern cuisines

- Schmaltz, clarified animal fat

- Dairy product

References

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- "Clarified butter – Glossary – How to cook". BBC Good Food. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- Walstra, P. Wouters, J. Geurts, T. (2006). Dairy Science and Technology, CRC Press – Taylor and Francis Group

- Amy Brown, Understanding Food: Principles and Preparation, 5th ed., 2014, ISBN 1133607152, p. 468

- Iyer, Raghavan (2008). 660 Curries, p. 21. New York: Workman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7611-3787-0.

- Jaffrey, Madhur (1982). Madhur Jaffrey’s Indian Cooking, p. 211. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-8120-6548-4.

- Sahni, Julie (1998). Julie Sahni’s Introduction to Indian Cooking, p. 217 under “usli ghee.” Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-976-8.

- Landis, Denise (2003). All About Ghee The New York Times – Food Chain