Politics of Indonesia

The politics of Indonesia take place in the framework of a presidential representative democratic republic whereby the President of Indonesia is both head of state and head of government and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the two People's Representative Councils. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.[1]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Indonesia |

|

|

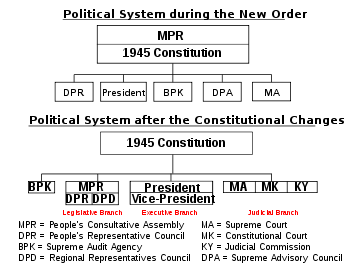

The 1945 constitution provided for a limited separation of executive, legislative and judicial power. The governmental system has been described as "presidential with parliamentary characteristics".[1] Following the Indonesian riots of May 1998 and the resignation of President Suharto, several political reforms were set in motion via amendments to the Constitution of Indonesia, which resulted in changes to all branches of government.

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Indonesia a "flawed democracy" in 2019.[2]

History

Liberal Democracy and Guided Democracy

An era of Liberal Democracy (Indonesian: Demokrasi Liberal) in Indonesia began on 17 August 1950 following the dissolution of the federal United States of Indonesia less than a year after its formation, and ended with the imposition of martial law and President Sukarno's 1959 Decree regarding the introduction of Guided Democracy (Indonesian: Demokrasi Terpimpin) on 5 July. It saw a number of important events, including the 1955 Bandung Conference, Indonesia's first general and Constitutional Assembly elections, and an extended period of political instability, with no cabinet lasting as long as two years.

From 1957, Guided Democracy was the political system in place until the New Order began in 1966. It was the brainchild of President Sukarno, and was an attempt to bring about political stability. He believed that Western-style democracy was inappropriate for Indonesia's situation. Instead, he sought a system based on the traditional village system of discussion and consensus, which occurred under the guidance of village elders.

Transition to the New Order

The transition to the "New Order" in the mid-1960s, ousted Sukarno after 22 years in the position. One of the most tumultuous periods in the country's modern history, it was the commencement of Suharto's three-decade presidency. Described as the great dhalang ("puppet master"), Sukarno drew power from balancing the opposing and increasingly antagonistic forces of the army and the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI).

By 1965, the PKI extensively penetrated all levels of government and gained influence at the expense of the army.[3] On 30 September 1965, six of the military's most senior officers were killed in an action (generally labelled an "attempted coup") by the so-called 30 September Movement, a group from within the armed forces. Within a few hours, Major General Suharto mobilised forces under his command and took control of Jakarta. Anti-communists, initially following the army's lead, went on a violent purge of communists throughout the country, killing an estimated half million people and destroying the PKI, which was officially blamed for the crisis.[4][5]

The politically weakened Sukarno was forced to transfer key political and military powers to General Suharto, who had become head of the armed forces. In March 1967, the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly (MPRS) named General Suharto acting president. He was formally appointed president one year later. Sukarno lived under virtual house arrest until his death in 1970. In contrast to the stormy nationalism, revolutionary rhetoric, and economic failure that characterised the early 1960s under the left-leaning Sukarno, Suharto's pro-Western "New Order" stabilised the economy but continued with the official state philosophy of Pancasila.

New Order

The New Order (Indonesian: Orde Baru) is the term coined by President Suharto to characterise his regime as he came to power in 1966. He used this term to contrast his rule with that of his predecessor, Sukarno (dubbed the "Old Order," or Orde Lama). The term "New Order" in more recent times has become synonymous with the Suharto years (1966–1998).

Immediately following the attempted coup in 1965, the political situation was uncertain, but the New Order found much popular support from groups wanting a separation from Indonesia's problems since its independence. The 'generation of 66' (Angkatan 66) epitomised talk of a new group of young leaders and new intellectual thought. Following communal and political conflicts, and economic collapse and social breakdown of the late 1950s through to the mid-1960s, the New Order was committed to achieving and maintaining political order, economic development, and the removal of mass participation in the political process. The features of the New Order established from the late 1960s were thus a strong political role for the military, the bureaucratisation and corporatisation of political and societal organisations, and selective but effective repression of opponents. Strident anti-communism remained a hallmark of the regime for its subsequent 32 years.

Within a few years, however, many of its original allies had become indifferent or averse to the New Order, which comprised a military faction supported by a narrow civilian group. Among much of the pro-democracy movement which forced Suharto to resign in 1998 and then gained power, the term "New Order" has come to be used pejoratively. It is frequently employed to describe figures who were either tied to the New Order, or who upheld the practises of his authoritarian regime, such as corruption, collusion and nepotism (widely known by the acronym KKN: korupsi, kolusi, nepotisme).[6]

Reform era

The Post-Suharto era began with the fall of Suharto in 1998 during which Indonesia has been in a period of transition, an era known as Reformasi (English: Reform[7][8][9]). This period has seen a more open and liberal political-social environment.

A process of constitutional reform lasted from 1999 to 2002, with four amendments producing major changes.[10] Among these are term limits of up to 2 five-year terms for the President and Vice-President, and measures to institute checks and balances. The highest state institution is the People's Consultative Assembly (Indonesian: Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR), whose functions previously included electing the president and vice-president (since 2004 the president has been elected directly by the people), establishing broad guidelines of state policy, and amending the constitution. The 695-member MPR includes all 550 members of the People's Representative Council (Indonesian: Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR) plus 130 members of Regional Representative Council (Indonesian: Dewan Perwakilan Daerah, DPD) elected by the 26 provincial parliaments and 65 appointed members from societal groups.[11]

The DPR, which is the premier legislative institution, originally included 462 members elected through a mixed proportional/district representational system and thirty-eight appointed members of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) and police (POLRI). TNI/POLRI representation in the DPR and MPR ended in 2004. Societal group representation in the MPR was eliminated in 2004 through further constitutional change.[12][13] Having served as rubberstamp bodies in the past, the DPR and MPR have gained considerable power and are increasingly assertive in oversight of the executive branch. Under constitutional changes in 2004, the MPR became a bicameral legislature, with the creation of the DPD, in which each province is represented by four members, although its legislative powers are more limited than those of the DPR. Through his/her appointed cabinet, the president retains the authority to conduct the administration of the government.[14]

A general election in June 1999 produced the first freely elected national, provincial and regional parliaments in over 40 years. In October 1999, the MPR elected a compromise candidate, Abdurrahman Wahid, as the country's fourth president, and Megawati Sukarnoputri—a daughter of Sukarno—as the vice-president. Megawati's PDI-P party had won the largest share of the vote (34%) in the general election, while Golkar, the dominant party during the New Order, came in second (22%). Several other, mostly Islamic parties won shares large enough to be seated in the DPR. Further democratic elections took place in 2004, 2009 and 2014.

Executive branch

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Joko Widodo | Indonesian Democratic Party-Struggle | 20 October 2014 |

| Vice-President | Ma'ruf Amin | No Party | 20 October 2019 |

The executive branch of Indonesia is headed by a president, who is head of government and head of state. The president is elected by general election and can serve up to two five-year terms if reelected.[15] The executive branch also includes a vice-president and a cabinet. All bills need joint approval between the executive and the legislature to become law, meaning the president has veto power over all legislation.[16] The president also has the power to issue presidential decrees that have policy effects, and they are also in charge of Indonesia's international relationships, although they require legislative approval for treaties.[15] Prior to 2004, the president was chosen by the MPR, but the president is currently selected through national election.[17] The last election was held in April 2019, and incumbent Joko Widodo emerged as the winner.[18]

Legislative branch

The MPR is the legislative branch of Indonesia's political system. The MPR is composed of two houses: the DPR, which is commonly called the People's Representative Council, and the DPD, which is called the Regional Representative Council. The 575 DPR parliamentarians are elected through multi-member electoral districts, whereas 4 DPD parliamentarians are elected in each of Indonesia's 34 provinces. The DPR holds most of the legislative power because it has the sole power to pass laws. The DPD acts as a supplementary body to the DPR; it can propose bills, offer its opinion and participate in discussions, but it has no legal power. The MPR itself has power outside of those given to the individual houses. It can amend the constitution, inaugurate the president and conduct impeachment procudures. When the MPR acts in this function, it does so by simply combining the members of the two houses.[16][17]

Political parties and elections

The General Elections Commission (Indonesian: Komisi Pemilihan Umum, KPU) is the body that is responsible for running both parliamentary and presidential elections. Article 22E(5) of the Constitution rules that the KPU is national, permanent, and independent. Prior to the 2004 elections, the KPU was made up of members who were also members of political parties. However, members of KPU must now be non-partisan.

| Candidate | Running mate | Parties | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joko Widodo | Ma'ruf Amin | Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan) | 85,607,362 | 55.50 | |

| Prabowo Subianto | Sandiaga Uno | Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya) | 68,650,239 | 44.50 | |

| Total | 154,257,601 | 100.00 | |||

| Valid votes | 154,257,601 | 97.62 | |||

| Spoilt and null votes | 3,754,905 | 2.38 | |||

| Turnout | 158,012,506 | 81.93 | |||

| Abstentions | 34,853,748 | 18.07 | |||

| Registered voters | 192,866,254 | ||||

| Source: KPU | |||||

| Parties | Votes | Seats | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | Swing | Total | +/- | % | ||

| Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, PDI–P) | 27,053,961 | 19.33 | 128 | 22.26 | |||

| Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, Gerindra) | 17,594,839 | 12.57 | 78 | 13.57 | |||

| Golkar (Partai Golongan Karya) | 17,229,789 | 12.31 | 85 | 14.78 | |||

| National Awakening Party (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa, PKB) | 13,570,097 | 9.69 | 58 | 10.09 | |||

| Nasdem Party (Partai Nasdem, Nasdem) | 12,661,792 | 9.05 | 59 | 10.26 | |||

| Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, PKS) | 11,493,663 | 8.21 | 50 | 8.70 | |||

| Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD) | 10,876,507 | 7.77 | 54 | 9.39 | |||

| National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN) | 9,572,623 | 6.84 | 44 | 7.65 | |||

| United Development Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan, PPP) | 6,323,147 | 4.52 | 19 | 3.30 | |||

| Perindo Party (Partai Perindo, Perindo) | 3,738,320 | 2.67 | New | 0 | New | 0.00 | |

| Berkarya Party (Partai Berkarya, Berkarya) | 2,929,495 | 2.09 | New | 0 | New | 0.00 | |

| Indonesian Solidarity Party (Partai Solidaritas Indonesia, PSI) | 2,650,361 | 1.89 | New | 0 | New | 0.00 | |

| People's Conscience Party (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat, Hanura) | 2,161,507 | 1.54 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang, PBB) | 1,099,848 | 0.79 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Garuda Party (Partai Garuda, Garuda) | 702,536 | 0.50 | New | 0 | New | 0.00 | |

| Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia, PKPI) | 312,775 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Total | 139,971,260 | 100.00 | 575 | 100.00 | |||

| Spoilt and null votes | 17,503,953 | 11.12 | |||||

| Voter turnout | 157,475,213 | 83.86 | |||||

| Electorate | 187,781,884 | ||||||

| Source: KPU, Jakarta Globe 21 May 2019 Medcom.id 1 October 2019 | |||||||

Judicial branch

Both The Supreme Court of Indonesia (Indonesian: Mahkamah Agung) and The Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) are the highest level of the judicial branch. The Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) listens to disputes concerning legality of law, general elections, dissolution of political parties, and the scope of authority of state institution. It has 9 judges and its judges are appointed by the DPR, the President and the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court of Indonesia hears final cessation appeals and conducts case reviews. It has 51 judges divided into 8 chambers. Its judges are nominated by the Judicial Commission of Indonesia and appointed by the President. Most civil disputes appear before the State Court (Pengadilan Negeri); appeals are heard before the High Court (Pengadilan Tinggi). Other courts include the Commercial Court, which handles bankruptcy and insolvency; the State Administrative Court (Pengadilan Tata Usaha Negara) to hear administrative law cases against the government; and the Religious Court (Pengadilan Agama) to deal with codified Islamic Law (sharia) cases.[20] Additionally, the Judicial Commission (Komisi Yudisial) monitors the performance of judges.

Foreign relations

During the regime of president Suharto, Indonesia built strong relations with the United States and had difficult relations with the People's Republic of China owing to Indonesia's anti-communist policies and domestic tensions with the Chinese community. It received international denunciation for its annexation of East Timor in 1978. Indonesia is a founding member of the Association of South East Asian Nations, and thereby a member of both ASEAN+3 and the East Asia Summit.

Since the 1980s, Indonesia has worked to develop close political and economic ties between Southeast Asian countries, and is also influential in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Indonesia was heavily criticised between 1975 and 1999 for allegedly suppressing human rights in East Timor, and for supporting violence against the East Timorese following the latter's secession and independence in 1999. Since 2001, the government of Indonesia has co-operated with the US in cracking down on Islamic fundamentalism and terrorist groups.

See also

- Constitution of Indonesia

- Administrative divisions of Indonesia

- List of presidents of Indonesia

- List of Vice-Presidents of Indonesia

- Foreign relations of Indonesia

- Corruption in Indonesia

References

- King, Blair. A Inside Indonesia:Constitutional tinkering: The search for consensus is taking time Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine access date 23 May 2009

- The Economist Intelligence Unit (8 January 2019). "Democracy Index 2019". Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Ricklefs (1991), pp. 271-283

- Chris Hilton (writer and director) (2001). Shadowplay (Television documentary). Vagabond Films and Hilton Cordell Productions.; Ricklefs (1991), pages 280–283, 284, 287–290

- Robert Cribb (2002). "Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966". Asian Survey. 42 (4): 550–563. doi:10.1525/as.2002.42.4.550.; Friend (2003), page 107-109, 113.

- Stop talk of KKN Archived 26 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Jakarta Post (24 August 2001).

- US Indonesia Diplomatic and Political Cooperation Handbook, Int'l Business Publications, 2007, ISBN 1433053306, page CRS-5

- Robin Bush, Nahdlatul Ulama and the Struggle for Power Within Islam and Politics in Indonesia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009, ISBN 9812308768, page 111

- Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Lonely Planet Indonesia, 2010, ISBN 1741048303, page 49

- Indrayana 2008, pp. 360-361.

- Indrayana 2008, pp. 361-362.

- Indrayana 2008, pp. 293-296.

- "Indonesia's military: Business as usual". 16 August 2002.

- Indrayana 2008, pp. 265,361,441.

- Laiman, Alamo; Reni, Dewi; Lengkong, Ronald; Ardiyanto, Sigit (2015). "UPDATE: The Indonesian Legal System and Legal Research". Hauser Global Law School Program. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Aspinall; Mietzner (2011). "People's Forum or Chamber of Cronies". Problems of Democratisation of Indonesia.

- Indrayana 2008.

- "Indonesia election: Joko Widodo re-elected as president". 21 May 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Ghina Ghaliya (21 May 2019). "KPU names Jokowi winner of election". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Cammack, Mark E.; Feener, R. Michael (January 2012). "The Islamic Legal System in Indonesia" (PDF). Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

Further reading

- Indrayana, Denny (2008). Indonesian Constitutional Reform 1999-2002: An Evaluation of Constitution-Making in Transition. Jakarta: Kompas Book Publishing. ISBN 978-979-709-394-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Rourke, Kevin (2002). Reformasi: the struggle for power in post-Soeharto Indonesia. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-754-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwarz, Adam (2000). A nation in waiting: Indonesia's search for stability. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3650-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)