Grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are used to convert grass and other forage into meat, milk, wool and other products, often on land unsuitable for arable farming.

Farmers may employ many different strategies of grazing for optimum production: grazing may be continuous, seasonal, or rotational within a grazing period. Longer rotations are found in ley farming, alternating arable and fodder crops; in rest rotation, deferred rotation, and mob grazing, giving grasses a longer time to recover or leaving land fallow. Patch-burn sets up a rotation of fresh grass after burning with two years of rest. Conservation grazing deliberately uses grazing animals to improve the biodiversity of a site.

Grazing has existed since the birth of agriculture; sheep and goats were domesticated by nomads before the first settlements were created around 7000 BC, enabling cattle and pigs to be kept.

Grazing's ecological effects can be positive and include redistributing nutrients, keeping grasslands open or favouring a particular species over another. There can also be negative effects to the environment.

History

Sheep, goats cattle, and pigs were domesticated early in the history of agriculture. Sheep were domesticated first, soon followed by goats; both species were suitable for nomadic peoples. Cattle and pigs were domesticated somewhat later, around 7000 BC, once people started to live in fixed settlements.[1]

In America, livestock were grazed on public land from the Civil War. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 was enacted after the Great Depression to regulate the use of public land for grazing purposes.[2]

Production

Grazing by livestock is a means of deriving food and income from lands which are generally unsuitable for arable farming: for example in the United States, some 85% of grazing land is not suitable for crops.[3]

According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization, about 60% of the world's grassland (just less than half of the world's usable surface) is covered by grazing systems. It states that "Grazing systems supply about 9 percent of the world's production of beef and about 30 percent of the world's production of sheep and goat meat. For an estimated 100 million people in arid areas, and probably a similar number in other zones, grazing livestock is the only possible source of livelihood."[4]

Management

Grazing management has two overall goals, each of which is multifaceted:

- Protecting the quality of the pasturage against deterioration by overgrazing

- In other words, maintain the sustainability of the pasturage

- Protecting the health of the animals against acute threats, such as:

- Grass tetany and nitrate poisoning

- Trace element overdose, such as molybdenum and selenium poisoning

- Grass sickness and laminitis in horses

- Milk sickness in calves

A proper land use and grazing management technique balances maintaining forage and livestock production, while still maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services.[5][6] It does this by allowing sufficient recovery periods for regrowth. Producers can keep a low density on a pasture, so as not to overgraze. Controlled burning of the land can help in the regrowth of plants.[7] Although grazing can be problematic for the ecosystem, well-managed grazing techniques can reverse damage and improve the land.

On commons in England and Wales, rights of pasture (grassland grazing) and pannage (forest grazing) for each commoner are tightly defined by number and type of animal, and by the time of year when certain rights could be exercised. For example, the occupier of a particular cottage might be allowed to graze fifteen cattle, four horses, ponies or donkeys, and fifty geese, while the numbers allowed for their neighbours would probably be different. On some commons (such as the New Forest and adjoining commons), the rights are not limited by numbers, and instead a 'marking fee' is paid each year for each animal 'turned out'.[8] However, if excessive use was made of the common, for example, in overgrazing, a common would be 'stinted', that is, a limit would be put on the number of animals each commoner was allowed to graze. These regulations were responsive to demographic and economic pressure. Thus, rather than let a common become degraded, access was restricted even further.[9]

Systems

Ranchers and range science researchers have developed grazing systems to improve sustainable forage production for livestock. These can be contrasted with intensive animal farming on feedlots.

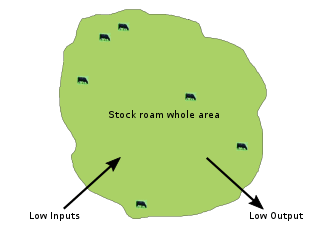

Continuous

With continuous grazing, livestock is allowed access to the same grazing area throughout the year.[10]

Seasonal

Seasonal grazing incorporates "grazing animals on a particular area for only part of the year". This allows the land that is not being grazed to rest and allow for new forage to grow.[11]

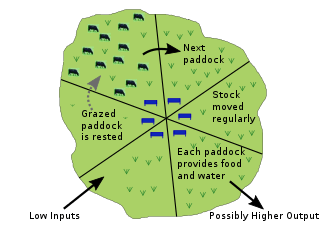

Rotational

Rotational grazing "involves dividing the range into several pastures and then grazing each in sequence throughout the grazing period". Utilizing rotational grazing can improve livestock distribution while incorporating rest period for new forage.[11]

Ley farming

In ley farming, pastures are not permanently planted, but alternated between fodder crops and/or arable crops.[12]

Rest rotation

Rest rotation grazing "divides the range into at least four pastures. One pasture remains rested throughout the year and grazing is rotated amongst the residual pastures." This grazing system can be especially beneficial when using sensitive grass that requires time for rest and regrowth.[11]

Deferred rotation

Deferred rotation "involves at least two pastures with one not grazed until after seed-set". By using deferred rotation, grasses can achieve maximum growth during the period when no grazing occurs.[11]

Patch-burn

Patch-burn grazing burns a third of a pasture each year, no matter the size of the pasture. This burned patch attracts grazers (cattle or bison) that graze the area heavily because of the fresh grasses that grow as a result. The other patches receive little to no grazing. During the next two years the next two patches are burned consecutively, then the cycle begins anew. In this way, patches receive two years of rest and recovery from the heavy grazing. This technique results in a diversity of habitats that different prairie plants and birds can utilize—mimicking the effects of the pre-historical bison/fire relationship, whereby bison heavily graze one area and other areas have opportunity to rest.[7] The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in northeastern Oklahoma has been patch-burn grazed with bison herds for over ten years. These efforts have effectively restored the bison/fire relationship on a large landscape scale of 30,000 acres (12,000 ha).[13] In the grazed heathland of Devon the periodic burning is known as swailing.[14]

Riparian area management

Riparian area grazing is geared more towards improving wildlife and their habitats. It uses fencing to keep livestock off ranges near streams or water areas until after wildlife or waterfowl periods, or to limit the amount of grazing to a short period of time.[11]

Conservation grazing

Conservation grazing is the use of grazing animals to help improve the biodiversity of a site. Due to their hardy nature, rare and native breeds are often used in conservation grazing.[15] In some cases, to re-establish traditional hay meadows, cattle such as the English Longhorn and Highland are used to provide grazing.[16]

Cell grazing

A form of rotational grazing using as many small paddocks as fencing allows, said to be more sustainable.[17]

Environmental considerations

Ecology

A number of ecological effects derive from grazing, and these may be either positive or negative. Negative effects of grazing may include overgrazing, increased soil erosion, compaction and degradation, deforestation, biodiversity loss,[4] and adverse water quality impacts from run-off.[19][20] Sometimes grazers can have beneficial environmental effects such as improving the soil with nutrient redistribution and aerating the soil by trampling, and by controlling fire and increasing biodiversity by removing biomass, controlling shrub growth and dispersing seeds.[4] In some habitats, appropriate levels of grazing may be effective in restoring or maintaining native grass and herb diversity in rangeland that has been disturbed by overgrazing, lack of grazing (such as by the removal of wild grazing animals), or by other human disturbance.[21][22] Conservation grazing is the use of grazers to manage such habitats, often to replicate the ecological effects of the wild relatives of domestic livestock, or those of other species now absent or extinct.[23]

Grazer urine and faeces "recycle nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and other plant nutrients and return them to the soil".[24] Grazing can reduce the accumulation of litter (organic matter) in some seasons and areas,[25] but can also increase it, which may help to combat soil erosion.[26] This acts as nutrition for insects and organisms found within the soil. These organisms "aid in carbon sequestration and water filtration".[24]

When grass is grazed, dead grass and litter are reduced which is advantageous for birds such as waterfowl. Grazing can increase biodiversity. Without grazing, many of the same grasses grow, for example brome and bluegrass, consequently creating a monoculture.[25] The ecosystems of North American tallgrass prairies are controlled to a large extent by nitrogen availability, which is itself controlled by interactions between fires and grazing by large herbivores. Fires in Spring enhance growth of certain grasses, and herbivores preferentially graze these grasses, creating a system of checks and balances, and allowing higher plant biodiversity.[27] In Europe heathland is a cultural landscape which requires grazing by cattle, sheep or other grazers to be maintained.[28]

Conservation

An author of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report Livestock's Long Shadow,[29] stated in an interview:[30]

Grazing occupies 26 percent of the Earth's terrestrial surface ... feed crop production requires about a third of all arable land ... Expansion of grazing land for livestock is also a leading cause of deforestation, especially in Latin America... In the Amazon basin alone, about 70 percent of previously forested land is used as pasture, while feed crops cover a large part of the remainder.

Much grazing land has resulted from a process of clearance or drainage of other habitats such as woodland or wetland.[31]

According to the opinion of the Center for Biological Diversity, extensive grazing of livestock in the arid lands of the southwestern USA has many negative impacts on the local biodiversity there.[32]

Cattle destroy native vegetation, damage soils and stream banks, and contaminate waterways with fecal waste. After decades of livestock grazing, once-lush streams and riparian forests have been reduced to flat, dry wastelands; once-rich topsoil has been turned to dust, causing soil erosion, stream sedimentation and wholesale elimination of some aquatic habitats

In arid climates such as the Southwestern United States, livestock grazing has severely degraded riparian areas, the wetland environment adjacent to rivers or streams. The Environmental Protection Agency states that agriculture has a greater impact on stream and river contamination than any other nonpoint source. Improper grazing of riparian areas can contribute to nonpoint source pollution of riparian areas.[33] Riparian zones in arid and semiarid environments have been called biodiversity hotspots.[34] The water, higher biomass, favorable microclimate and periodic flood events together create higher biological diversity than in the surrounding uplands.[35] In 1990, "according to the Arizona state park department, over 90% of the original riparian zones of Arizona and New Mexico are gone". A 1988 report of the Government Accountability Office estimated that 90% of the 5,300 miles of riparian habitat managed by the Bureau of Land Management in Colorado was in unsatisfactory condition, as was 80% of Idaho's riparian zones, concluding that "poorly managed livestock grazing is the major cause of degraded riparian habitat on federal rangelands."[36]

A 2013 FAO report estimated livestock were responsible for 14.5% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.[37][38] Grazing is common in New Zealand; in 2004 methane and nitrous oxide from agriculture made up a bit less than half of New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions, of which most is attributable to livestock.[39] A 2008 United States Environmental Protection Agency report on emissions found agriculture was responsible for 6% of total United States greenhouse gas emissions in 2006. This included rice production, enteric fermentation in domestic livestock, livestock manure management, and agricultural soil management, but omitted some things which might be attributable to agriculture.[40] Studies comparing the methane emissions from grazing and feedlot cattle concluded that grass-fed cattle produce much more methane than grain-fed cattle.[41][42][43] One study in the Journal of Animal Science found four times as much, and stated: "these measurements clearly document higher CH4 production for cattle receiving low-quality, high-fiber diets than for cattle fed high-grain diets."[41]

See also

References

- Gascoigne, Bamber. "HISTORY OF THE DOMESTICATION OF ANIMALS". History World. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "History of Public Land Livestock Grazing". Retrieved 1 Dec 2008 Archived 2008-11-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fact Sheet: The Environment and Cattle Production" (PDF). Cattlemen's Beefboard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 8 Dec 2008.

- de Haan, Cees; Steinfeld, Henning; Blackburn, Harvey (1997). "Chapter 2: Livestock grazing systems & the environment". Livestock & the Environment: Finding a Balance. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities (under auspices of the Food and Agriculture Organization).

- James M. Bullock, Richard G. Jefferson, Tim H. Blackstock, Robin J. Pakeman, Bridget A. Emmett, Richard J. Pywell, J. Philip Grime and Jonathan Silvertown (June 2011). "Chapter 6 - Semi-natural Grasslands". UK National Ecosystem Assessment: Technical Report (Report). UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. pp. 162–187. Retrieved 17 October 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Mountains, Moorlands and Heaths; National Ecosystem Assessment".

- Fuhlendorf, S. D.; Engle, D. M. (2004). "Application of the fire–grazing interaction to restore a shifting mosaic on tallgrass prairie". Journal of Applied Ecology. 41 (4): 604–614. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00937.x.

- Forest rights.

- Susan Jane Buck Cox (1985). "No tragedy on the Commons" (PDF). Environmental Ethics. 7: 49–62. doi:10.5840/enviroethics1985716.

- D. D. Briske, J. D. Derner, J. R. Brown, S. D. Fuhlendorf, W. R. Teague, K. M. Havstad, R. L. Gillen, A. J. Ash, W. D. Willms, (2008) Rotational Grazing on Rangelands: Reconciliation of Perception and Experimental Evidence Archived 2015-09-26 at the Wayback Machine. Rangeland Ecology & Management: January 2008, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 3-17

- "Grazing Systems". Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia. Retrieved 1 Dec 2008 Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Ikande, Mary (2018). "Ley farming advantages and disadvantages". Ask Legit. Legit (Nigeria). Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "The Nature Conservancy in Oklahoma". www.nature.org. Archived from the original on 2011-02-23. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- "Dartmoor fire 'largest in years'". BBC. 7 April 2013.

- "Conservation grazing". Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Archived from the original on 2016-04-29. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- "Shapwick Moor Nature Reserve". Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "Grazing strategies". Meat & Livestock Australia. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Salatin, Joel. "Tall grass mob stocking" (PDF). Acres USA May 2008 vol 8 no 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Schindler, David W., Vallentyne, John R. (2008). The Algal Bowl: Overfertilization of the World's Freshwaters and Estuaries, University of Alberta Press, ISBN 0-88864-484-1.

- Nemecek, T.; Poore, J. (2018-06-01). "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers". Science. 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29853680.

- Launchbaugh, Karen (2006). Targeted Grazing: A natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement. National Sheep Industry Improvement Center in Cooperation with the American Sheep Industry Association.

- History distribution and challenges to bison recovery in the northern Chihuahuan desert Rurik, L., G. Ceballos, C. Curtin, P. J. P. Gogan, J. Pacheco, and J. Truett. Conservation Biology, 2007, 21(6): 1487–1494.

- What is Conservation Grazing? Grazing Advice Partnership, UK, 2009.

- "Benefits of Grazing Cattle on the Prairie". Native Habitat Organization. Retrieved 1 Dec 2008 Archived 2007-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "Waterfowl area grazing benefits birds, cattle - The Fergus Falls Daily Journal". 21 February 2008.

- Dalrymple, R.L.. "Fringe Benefits of Rotational Stocking". Intensive Grazing Benefits. Noble Foundation. Retrieved 1 Dec 2008 Archived 2008-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bison Grazing Increases Biodiversity". news.bio-medicine.org.

- Rackham, Oliver (1997). The History of the Countryside. Phoenix. p. 282.

- Henning Steinfeld, Pierre Gerber, Tom Wassenaar, Vincent Castel, Mauricio Rosales, Cees de Haan (2006). Livestock's long shadow (PDF) (Report). Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 280. ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. Retrieved 27 September 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Harmful Environmental Effects Of Livestock Production On The Planet 'Increasingly Serious,' Says Panel". ScienceDaily. Stanford University. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- A. Crofts and R.G. Jefferson eds. "Lowland Grassland Management Handbook".CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Center for Biological Diversity|source=Grazing

- Hoorman, James; McCutcheon, Jeff. "Negative Effects of Livestock Grazing Riparian Areas". ohioline.osu.edu. Ohio State University School of Environment and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Luoma, Jon (September 1986). "Discouraging Words". Audubon. 88 (92).

- Kauffman, J. Boone. "Lifeblood of the West". Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- Wuerthner, George (September–October 1990). "The Price is Wrong". Sierra.

- "Tackling climate change through livestock // FAO's Animal Production and Health Division". Fao.org. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities (PDF) (Report). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). pp. 1–139. ISBN 978-92-5-107921-8. Retrieved 3 October 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry – Voluntary Greenhouse Gas Reporting Feasibility Study – Summary". Maf.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 2010-05-26. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Reports Archived 2011-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Harper LA; Denmead OT; Freney JR; Byers FM (Jun 1999). "Direct measurements of methane emissions from grazing and feedlot cattle". J Anim Sci. 77 (6): 1392–401. doi:10.2527/1999.7761392x. PMID 10375217. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Capper, JL (Apr 10, 2012). "Is the Grass Always Greener? Comparing the Environmental Impact of Conventional, Natural and Grass-Fed Beef Production Systems". Animals. 2 (2): 127–43. doi:10.3390/ani2020127. PMC 4494320. PMID 26486913.

- Pelletier N; Pirogb R; Rasmussen R (Jul 2010). "Comparative life cycle environmental impacts of three beef production strategies in the Upper Midwestern United States". Agricultural Systems. 103 (6): 380–389. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2010.03.009.

External links

![]()

| Look up grazing or grazer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |