Battle of the Falkland Islands

The Battle of the Falkland Islands was a First World War naval action between the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy on 8 December 1914 in the South Atlantic. The British, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, sent a large force to track down and destroy the German cruiser squadron. The battle is commemorated every year on 8 December in the Falkland Islands as a public holiday.

| Battle of the Falkland Islands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First World War | |||||||

.jpg) Battle of the Falkland Islands, William Lionel Wyllie | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 battlecruisers 3 armoured cruisers 2 light cruisers |

2 armoured cruisers 3 light cruisers 3 transport ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10 killed 19 wounded |

1,871 killed 215 captured 2 armoured cruisers sunk 2 light cruisers sunk 2 transports scuttled | ||||||

Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee—commanding the German squadron of two armoured cruisers, SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the light cruisers SMS Nürnberg, Dresden and Leipzig, and the colliers SS Baden, SS Santa Isabel, and SS Seydlitz[4][5]—attempted to raid the British supply base at Stanley in the Falkland Islands. The British squadron—consisting of the battlecruisers HMS Invincible and Inflexible, the armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon, Cornwall and Kent, the armed merchant cruiser HMS Macedonia and the light cruisers HMS Bristol and Glasgow—had arrived in the port the day before.

Visibility was at its maximum; the sea was placid with a gentle breeze, and the day was bright and sunny. The vanguard cruisers of the German squadron were detected early. By nine o'clock that morning, the British battlecruisers and cruisers were in hot pursuit of the German vessels. All except Dresden and Seydlitz were hunted down and sunk.

Background

The British battlecruisers each mounted eight 12 in (305 mm) guns, whereas Spee's best ships (Scharnhorst and Gneisenau) were equipped with eight 210 mm (8.3 in) pieces. Additionally, the battlecruisers could make 25.5 knots (47.2 km/h; 29.3 mph) against Spee's 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph); thus, the British battlecruisers not only significantly outgunned their opponents, but could outrun them too. The obsolete pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus had been grounded at Stanley to act as a makeshift defence battery for the area.

Spee's squadron

At the outbreak of hostilities, the German East Asia Squadron commanded by Spee was outclassed and outgunned by the Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy. Spee and the High Command did not believe Germany's Asian possessions could be defended and doubted the squadron could even survive in that theatre. Spee wanted to get his ships home and began by heading southeast across the Pacific, although he was pessimistic about their chances.

Spee's fleet won the Battle of Coronel off the coast of Coronel, Chile, on 1 November 1914, where his ships sank the cruisers HMS Good Hope (Admiral Cradock's flagship) and Monmouth. After the battle, on 3 November, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg entered Valparaíso harbour and were welcomed as heroes by the German population. Von Spee declined to join in the celebrations; when presented with a bouquet of flowers, he refused them, commenting that "these will do nicely for my grave".[6] As required under international law for belligerent ships in neutral countries, the ships left within 24 hours, moving to Mas Afuera, 400 mi (350 nmi; 640 km) off the Chilean coast. There they received news of the loss of the cruiser SMS Emden, which had previously detached from the squadron and had been raiding in the Indian Ocean. They also learned of the fall of the German colony at Tsingtao in China, which had been their home port. On 15 November, the squadron moved to Bahia San Quintin on the Chilean coast, where a ceremony was held to award 300 Iron Crosses, second class, to crew members, and an Iron Cross first class to Admiral Spee.[7]

Spee's officers counseled a return to Germany. The squadron had used half its ammunition at Coronel; the supply could not be replenished, and it was difficult even to obtain coal. Intelligence reports suggested that the British ships HMS Defence, Cornwall and Carnarvon were stationed in the River Plate, and that there had been no British warships at Stanley when recently visited by a steamer. Spee had been concerned about reports of a British battleship, Canopus, but its location was unknown. On 26 November, the squadron set sail for Cape Horn, which they reached on 1 December, then anchored at Picton Island, where they stayed for three days distributing coal from a captured British collier, the Drummuir, and hunting. On 6 December, the British vessel was scuttled and its crew transferred to the auxiliary Seydlitz. The same day Spee proposed to raid the Falkland Islands before setting course for Germany. The raid was unnecessary because the squadron now had as much coal as it could carry. Most of Spee's captains opposed the raid, but he nevertheless decided to proceed.[8]

British preparations

On 30 October, retired Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher was reappointed First Sea Lord to replace Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg, who had been forced to resign because of public outcry against a perceived German prince running the British navy, though Louis had been British and in the Royal Navy since the age of 14. On 3 November, Fisher was advised that Spee had been sighted off Valparaíso and acted to reinforce Cradock by ordering Defence, already sent to patrol the eastern coast of South America, to reinforce his squadron. On 4 November, news of the defeat at Coronel arrived. The blow to British naval prestige was palpable, and the British public was rather shocked. As a result, the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible were ordered to leave the Grand Fleet and sail to Plymouth for overhaul and preparation for service abroad. Chief of Staff at the Admiralty was Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee. Fisher had a long-standing disagreement with Sturdee, who had been one of those calling for his earlier dismissal as First Sea Lord in 1911, so he took the opportunity to appoint Sturdee Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic and Pacific, to command the new squadron from Invincible.[9]

On 11 November, Invincible and Inflexible left Devonport, although repairs to Invincible were incomplete and she sailed with workmen still aboard. Despite the urgency of the situation and their maximum speed of around 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph), the ships were forced to cruise at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) to conserve coal in order to complete the long journey south across the Atlantic. The two ships were also heavily loaded with supplies. Although secrecy of the mission was considered important so as to surprise Spee, Lieutenant Hirst from Glasgow heard locals discussing the forthcoming arrival of the ships while ashore at Cape Verde on 17 November; however the news did not reach Spee. Sturdee arrived at the Abrolhos Rocks on the 26 November, where Rear Admiral Stoddart awaited him with the remainder of the squadron.[10]

Sturdee announced his intention to depart for the Falkland Islands on 29 November. From there, the fast light cruisers Glasgow and Bristol would patrol seeking Spee, summoning reinforcements if they found him. Captain Luce of Glasgow, who had been at the battle of Coronel, objected that there was no need to wait so long and persuaded Sturdee to depart a day early. The squadron was delayed during the journey for 12 hours when a cable towing targets for practice-firing became wrapped around one of Invincible's propellers, but the ships arrived on the morning of 7 December. The two light cruisers moored in the inner part of Stanley Harbour, while the larger ships remained in the deeper outer harbour of Port William. Divers set about removing the offending cable from Invincible; Cornwall's boiler fires were extinguished to make repairs, and Bristol had one of her engines dismantled. The famous ship SS Great Britain—reduced to a coal bunker—supplied coal to Invincible and Inflexible. The armed merchant cruiser Macedonia was ordered to patrol the harbour, while Kent maintained steam in her boilers, ready to replace Macedonia the next day, 8 December; Spee's fleet arrived in the morning of the same day.[11]

An unlikely source of intelligence on the movement of the German ships was from Mrs Muriel Felton, wife of the manager of a sheep station at Fitzroy, and her maids Christina Goss and Marian Macleod. They were alone when Felton received a telephone call from Port Stanley advising that German ships were approaching the islands. The maids took turns riding to the top of a nearby hill to record the movements of the ships, which Felton relayed to Port Stanley by telephone. Her reports allowed Bristol and Macedonia to take up the best positions to intercept. The Admiralty later presented the women with silver plates and Felton received an OBE for her actions.[12][13][14][15]

Battle

Opening moves

Spee's cruisers—Gneisenau and Nürnberg—approached Stanley first. At the time, the entire British fleet was coaling. Some believe that, had Spee pressed the attack, Sturdee's ships would have been easy targets,[16] although this is a subject of conjecture and some controversy. Any British ship that tried to leave would have faced the full firepower of the German ships; having a vessel sunk might also have blocked the rest of the British squadron inside the harbour. However, the Germans were surprised by gunfire from an unexpected source: HMS Canopus, which had been grounded as a guardship and was behind a hill. This was enough to check the Germans' advance. The sight of the distinctive tripod masts of the British battlecruisers confirmed that they were facing a better-equipped enemy. HMS Kent was already making her way out of the harbour and had been ordered to pursue Spee's ships.

Made aware of the German ships, Sturdee had ordered the crews to breakfast, knowing that Canopus had bought them time while steam was raised.

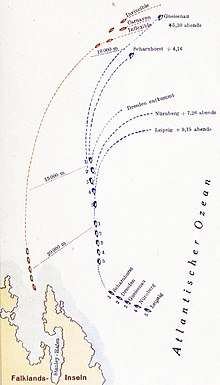

To Spee, with his crew battle-weary and his ships outgunned, the outcome seemed inevitable. Realising his danger too late, and having lost any chance to attack the British ships while they were at anchor, Spee and his squadron dashed for the open sea. The British left port around 10:00. Spee was ahead by 15 mi (13 nmi; 24 km), with the German ships in line abreast heading southeast, but there was plenty of daylight left for the faster battlecruisers to catch up.

Contact

It was 13:00 when the British battlecruisers opened fire, but it took them half an hour to get the range of SMS Leipzig. Realising that he could not outrun the British ships, Spee decided to engage them with his armoured cruisers alone, to give the light cruisers a chance to escape. He turned to fight just after 13:20. The German armoured cruisers had the advantage of a freshening north-west breeze, which caused the funnel smoke of the British ships to obscure their target practically throughout the action. Gneisenau's second-in-command Hans Pochhammer indicated that there was a long respite for the Germans during the early stages of the battle, as the British attempted unsuccessfully to force Admiral Spee away from his advantageous position.

Despite initial success by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in striking Invincible, the British capital ships suffered little damage. Spee then turned to escape, but the battlecruisers came within extreme firing range 40 minutes later.

HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible engaged Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, while Sturdee detached his cruisers to chase SMS Leipzig and SMS Nürnberg.

HMS Inflexible and HMS Invincible turned to fire broadsides at the armoured cruisers and Spee responded by trying to close the range. His flagship SMS Scharnhorst took extensive damage with funnels flattened, fires and a list. The list became worse at 16:04, and she sank by 16:17, taking von Spee and the entire crew with her. SMS Gneisenau continued to fire and evade until 17:15, by which time her ammunition had been exhausted, and her crew allowed her to sink at 18:02.[17] During her death throes, Admiral Sturdee continued to engage SMS Gneisenau with his two battlecruisers and the cruiser HMS Carnarvon, rather than detaching one of the battlecruisers to hunt down the escaping Dresden. 190 of SMS Gneisenau's crew were rescued from the water. Both of the British battlecruisers had received about 40 hits between them from the German ships, with one crewman killed and four injured.

Meanwhile, SMS Nürnberg and SMS Leipzig had run from the British cruisers. SMS Nürnberg was running at full speed but in need of maintenance, while the crew of the pursuing HMS Kent were pushing her boilers and engines to the limit. SMS Nürnberg finally turned for battle at 17:30. HMS Kent had the advantage in shell weight and armour. SMS Nürnberg suffered two boiler explosions around 18:30, giving the advantage in speed and manoeuvrability to HMS Kent. The German ship then rolled over and sank at 19:27 after a long chase. The cruisers HMS Glasgow and HMS Cornwall had chased down SMS Leipzig; HMS Glasgow closed to finish SMS Leipzig, which had run out of ammunition but was still flying her battle ensign. SMS Leipzig fired two flares, so HMS Glasgow ceased fire. At 21:23, more than 80 mi (70 nmi; 130 km) southeast of the Falklands, she also rolled over and sank, leaving only 18 survivors.

During the course of the main battles, Sturdee had despatched Captain Fanshawe on HMS Bristol, together with HMS Macedonia, to destroy the colliers.[5] Baden and Santa Isabel were chased, stopped, and (after removing the crews) sunk by HMS Bristol and HMS Macedonia at 19:00. Seydlitz had taken a separate course and escaped.[4][5]

Outcome

Casualties and damage were extremely disproportionate; the British suffered only very lightly. Admiral Spee and his two sons were among the German dead. Rescued German survivors, 215 total, became prisoners on the British ships. Most were from the Gneisenau, nine were from Nürnberg and 18 were from Leipzig. Scharnhorst was lost with all hands. One of Gneisenau's officers who lived had been the sole survivor on three different guns on the battered cruiser. He was pulled from the water saying he was a first cousin of the British commander (Stoddart).[18]

Of the known German force of eight ships, two escaped: the auxiliary Seydlitz and the light cruiser Dresden, which roamed at large for a further three months before her captain was cornered by a British squadron (Kent, Glasgow and Orama) off the Juan Fernández Islands on 14 March 1915. After fighting a short battle, Dresden's captain evacuated his ship and scuttled her by detonating the main ammunition magazine.

As a consequence of the battle, the German East Asia Squadron, Germany's only permanent overseas naval formation, effectively ceased to exist. Commerce raiding on the high seas by regular warships of the Kaiserliche Marine was brought to an end. However, Germany put several armed merchant vessels into service as commerce raiders until the end of the war (for example, see Felix von Luckner).

British Intelligence during the battle

After the battle, German naval experts were baffled at why Admiral Spee attacked the base and how the two squadrons could have met so coincidentally in so many thousands miles of open waters. Kaiser William II's handwritten note on the official report of the battle reads: "It remains a mystery what made Spee attack the Falkland Islands. See 'Mahan's Naval Strategy'."[19]

It was generally believed Spee was misled by the German admiralty into attacking the Falklands, a Royal Naval fuelling base, after receiving intelligence from the German wireless station at Valparaiso which reported the port free of Royal Navy warships. Despite the objection of three of his ships' captains, Spee proceeded to attack.[20][21]

However, in 1925 a German naval officer, Franz von Rintelen, interviewed Admiral William Reginald Hall, Director of the Admiraltry's Naval Intelligence Division (NID), and was informed that Spee's squadron had been lured towards the British battlecruisers by means of a fake signal sent in a German naval code broken by British cryptographers.[19] (Similarly, on 14 March 1915, SMS Dresden was intercepted by British ships while taking on coal at sea in a location identified by NID codebreakers).[22]

Scharnhorst wreck

The wreck of Scharnhorst was discovered on 4 December 2019, approximately 98 nautical miles (181 km; 113 mi) southeast of Stanley at a depth of 1,610 m (5,280 ft).[23]

Notes

- Jaques. Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. p. 346.

- Scott & Robertson. Many Were Held by the Sea: The Tragic Sinking of HMS Otranto. p. 16.

- "December 08: The Battle of the Falkland Islands". History.com This Day in History. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Battle of the Falkland Islands -names the three German auxiliary ships and states that Bristol and Macedonia sank the colliers Baden and Santa Isabel, while 'the other collier', Seydlitz, escaped.- www.worldwar1.co.uk, accessed 7 December 2019

- Battle of the Falkland Islands -SS Seydlitz listed as a 'hospital ship'- www.britishbattles.com, accessed 7 December 2019

- Massie, 2004, p. 237, citing Pitt pp. 66–67.

- Massie, 2004, pp. 251–52

- Massie, 2004, pp. 253–56

- Massie, 2004, p. 248

- Massie, 2004, p. 249

- Massie, 2004, pp. 249–51

- "United Empire". 14. 1923: 687. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ian J. Strange (1983). The Falkland Islands. David & Charles. p. 100. ISBN 0715385313.

- Paul G. Halpern (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Naval Institute Press. p. 99. ISBN 1557503524.

- "No. 30576". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 March 1918. p. 3287.

- "...the prospects should the Germans press home an attack without delay were far from pleasant." Corbett, J.S. British Official History – Naval Operations. (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1921) vol. I, chapter XXIX, cited in Baldwin, Hanson W. World War I: An Outline History. (New York: Grove Press, 1962) p. 46

- Regan, Geoffrey. Military Anecdotes (1992) p. 13 Guinness Publishing ISBN 0-85112-519-0

- Regan p. 14

- Franz von Rintelen (in English). The Dark Invader: Wartime Reminiscences of a German Naval Intelligence Officer (1998 ed.). Routledge. pp. 326. ISBN 0714647926.

- Halpern, p. 97

- Massie, 2004, p. 255

- Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0241108640.

- "German WWI wreck Scharnhorst discovered off Falklands". BBC News. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

References

- Bennett, Geoffrey (1962). Coronel and the Falklands. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335389.

- Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Irving, John (1927). Coronel and the Falklands. London: A. M. Philpot, ltd.

- Halpern, Paul (1994). A Naval History of World War I. United States: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-85728-295-7.

- Michael McNally (2012). Coronel and Falklands 1914; Duel in the South Atlantic. Osprey Campaign Series #248. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849086745

- Scott, R Neil (2012). Many Were Held by the Sea: The Tragic Sinking of HMS Otranto. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442213425.

- von Ritelen, Franz (1933). The Dark Invader. London: The Bodley Head/Penguin Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Falkland Islands. |

- Description of the battle from the diary of Captain JD Allen RN (HMS Kent)

- Battle of the Falkland Islands

- Battles of Coronel and the Falklands – a Pictorial Look

- Sailing vessel Fairport and her appearance during the battle

- Discovery of WW1 German Battlecruiser SMS Scharnhorst in Falklands waters