Scylla

In Greek mythology, Scylla[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈsɪlə/ SIL-ə; Greek: Σκύλλα, pronounced [skýl̚la], Skylla) is a legendary monster who lives on one side of a narrow channel of water, opposite her counterpart Charybdis. The two sides of the strait are within an arrow's range of each other—so close that sailors attempting to avoid Charybdis would pass dangerously close to Scylla and vice versa.

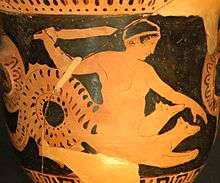

Scylla is first attested in Homer's Odyssey, where Odysseus and his crew encounter her and Charybdis on their travels. Later myth provides an origin story as a beautiful nymph who gets turned into a monster.[2]

The strait where Scylla dwells has been associated with the Strait of Messina between Calabria, a region of Southern Italy, and Sicily, for example, as in Book Three of Virgil's Aeneid.[3] The coastal town of Scilla in Calabria takes its name from the mythological figure of Scylla and it is said to be the home of the nymph.

The idiom "between Scylla and Charybdis" has come to mean being forced to choose between two similarly dangerous situations.

Parentage

The parentage of Scylla varies according to author.[lower-alpha 2] Homer, Ovid, Apollodorus, Servius, and a scholiast on Plato, all name Crataeis as the mother of Scylla.[4] Neither Homer nor Ovid mentions a father, but Apollodorus says that the father was either Trienus (Triton?) or Phorcus (a variant of Phorkys).[5] Similarly, the Plato scholiast, perhaps following Apollodorus, gives the father as Tyrrhenus or Phorcus,[6] while Eustathius on Homer, Odyssey 12.85, gives the father as Triton.

Other authors have Hecate as Scylla's mother. The Hesiodic Megalai Ehoiai gives Hecate and Phorbas as the parents of Scylla,[7] while Acusilaus says that Scylla's parents were Hecate and Phorkys (so also schol. Odyssey 12.85).[8]

Perhaps trying to reconcile these conflicting accounts, Apollonius of Rhodes says that Crataeis was another name for Hecate, and that she and Phorcys were the parents of Scylla.[9] Likewise, Semos of Delos[10] says that Crataeis was the daughter of Hecate and Triton, and mother of Scylla by Deimos. Stesichorus (alone) names Lamia as the mother of Scylla, possibly the Lamia who was the daughter of Poseidon,[11] while according to Gaius Julius Hyginus, Scylla was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna.[12]

Narratives

According to John Tzetzes[13] and Servius' commentary on the Aeneid,[14] Scylla was a beautiful naiad who was claimed by Poseidon, but the jealous Nereid Amphitrite turned her into a terrible monster by poisoning the water of the spring where Scylla would bathe.

A similar story is found in Hyginus,[15] according to whom Scylla was loved by Glaucus, but Glaucus himself was also loved by the goddess sorceress Circe. While Scylla was bathing in the sea, the jealous Circe poured a baleful potion into the sea water which caused Scylla to transform into a frightful monster with four eyes and six long snaky necks equipped with grisly heads, each of which contained three rows of sharp shark's teeth. Her body consisted of 12 tentacle-like legs and a cat's tail, while six dog's heads ringed her waist. In this form, she attacked the ships of passing sailors, seizing one of the crew with each of her heads.

In a late Greek myth, recorded in Eustathius' commentary on Homer and John Tzetzes,[16] Heracles encountered Scylla during a journey to Sicily and slew her. Her father, the sea-god Phorcys, then applied flaming torches to her body and restored her to life.

Homer's Odyssey

In Homer's Odyssey XII, Odysseus is advised by Circe to sail closer to Scylla, for Charybdis could drown his whole ship: "Hug Scylla's crag—sail on past her—top speed! Better by far to lose six men and keep your ship than lose your entire crew."[17] She also tells Odysseus to ask Scylla's mother, the river nymph Crataeis, to prevent Scylla from pouncing more than once. Odysseus successfully navigates the strait, but when he and his crew are momentarily distracted by Charybdis, Scylla snatches six sailors off the deck and devours them alive.

|

Ovid's Metamorphoses

According to Ovid,[19] the fisherman-turned-sea god Glaucus falls in love with the beautiful Scylla, but she is repulsed by his piscine form and flees to a promontory where he cannot follow. When Glaucus goes to Circe to request a love potion that will win Scylla's affections, the enchantress herself becomes enamored with him. Meeting with no success, Circe becomes hatefully jealous of her rival and therefore prepares a vial of poison and pours it into the sea pool where Scylla regularly bathed, transforming her into a thing of terror even to herself.

|

The story was later adapted into a five-act tragic opera, Scylla et Glaucus (1746), by the French composer Jean-Marie Leclair.

Keats' Endymion

In John Keats' loose retelling of Ovid's version of the myth of Scylla and Glaucus in Book 3 of Endymion (1818), the evil Circe does not transform Scylla into a monster but merely murders the beautiful nymph. Glaucus then takes her corpse to a crystal palace at the bottom of the ocean where lie the bodies of all lovers who have died at sea. After a thousand years, she is resurrected by Endymion and reunited with Glaucus.[21]

Paintings

At the Carolingian abbey of Corvey in Westphalia, a unique ninth-century wall painting depicts, among other things, Odysseus' fight with Scylla.[lower-alpha 3] an illustration not noted elsewhere in medieval arts.[22]

In the Renaissance and after, it was the story of Glaucus and Scylla that caught the imagination of painters across Europe. In Agostino Carracci's 1597 fresco cycle of The Loves of the Gods in the Farnese Gallery, the two are shown embracing, a conjunction that is not sanctioned by the myth.[lower-alpha 4] More orthodox versions show the maiden scrambling away from the amorous arms of the god, as in the oil on copper painting of Fillipo Lauri[lower-alpha 5] and the oil on canvas by Salvator Rosa in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen.[lower-alpha 6]

Other painters picture them divided by their respective elements of land and water, as in the paintings of the Flemish Bartholomäus Spranger (1587), now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.[lower-alpha 7] Some add the detail of Cupid aiming at the sea-god with his bow, as in the painting of Laurent de la Hyre (1640/4) in the J. Paul Getty Museum[lower-alpha 8] and that of Jacques Dumont le Romain (1726) at the Musée des beaux-arts de Troyes.[24] Two cupids can also be seen fluttering around the fleeing Scylla in the late painting of the scene by J. M. W. Turner (1841), now in the Kimbell Art Museum.[lower-alpha 9]

Peter Paul Rubens shows the moment when the horrified Scylla first begins to change, under the gaze of Glaucus (c.1636),[25] while Eglon van der Neer's 1695 painting in the Rijksmuseum shows Circe poisoning the water as Scylla prepares to bathe.[lower-alpha 10] There are also two Pre-Raphaelite treatments of the latter scene by John Melhuish Strudwick (1886)[26] and John William Waterhouse (Circe Invidiosa, 1892).[27]

Notes

- The Middle English Scylle (/ˈsɪliː/, reflecting Greek: Σκύλλη), is obsolete.

- For discussions of the parentage of Scylla, see Fowler, p. 32, Ogden, pp. 134-135 ; Gantz, pp. 731–732; and Frazer's note to Apollodorus, E7.20

- via Wikimedia

- at Wikimedia

- Magnoliabox Archived 2014-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- View on the Reproarte site; a preliminary drawing in MFA Boston is dated 1661

- Available in at Wikimedia

- View on the museum website[23]

- There is a more conventional print from around 1810/15 in the Tate Gallery

- View on Flickr

References

- Ogden (2013), p. 132.

- Ogden (2013), pp. 130–131.

- Virgil (2007). Aeneid. Translated by Ahl, Frederick. Oxford University Press. pp. 67.

- Homer, Odyssey 12.124–125; Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.749; Apollodorus, E7.20; Servius on Virgil Aeneid 3.420; schol. on Plato, Republic 9.588c.

- Ogden, p. 135; Gantz, p. 731.

- Fowler, p. 32

- Hesiod fr. 200 Most [= fr. 262 MW] (Most, pp. 310, 311).

- Acusilaus. fr. 42 Fowler (Fowler, p. 32).

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4. 828–829 (pp. 350–351).

- FGrHist 396 F 22

- Stesichorus, F220 PMG (Campbell, pp. 132–133).

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 151.

- John Tzetzes, On Lycophron 45

- Servius on Aeneid III. 420.

- Hyginus, Fabulae, 199

- On Lycophron 45

- Robert Fagles, The Odyssey 1996, XII.119ff.

- Fagles 1996 XII.275–79.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses xiii. 732ff., 905; xiv. 40ff.; translation by Nicholas Rowe and Samuel Garth is in GoogleBooks

- Ovid, Metamorphoses xiv.51–2

- Endymion Book III, line 401ff – via Project Gutenberg

- UNESCO: Corvey Abbey and Castle

- Glaucus and Scylla

- View on Flickr

- Musée Bonat, available in at Wikimedia

- View on Wikimedia

- Available on the website devoted to the artist

Bibliography

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius Rhodius, The Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton (trans 1912 ed.), W. Heinemann – via Internet Archive

- Campbell, David A., Greek Lyric III: Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, and Others, Harvard University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0674995253.

- Fowler, R. L., Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Hanfmann, George M. A., "The Scylla of Corvey and Her Ancestors" Dumbarton Oaks Papers 41 "Studies on Art and Archeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday" (1987), pp. 249–260.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Most, G.W., Hesiod: The Shield, Catalogue, Other Fragments, Loeb Classical Library, No. 503, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2007, 2018. ISBN 978-0-674-99721-9. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199557325.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stesichorus, in Greek Lyric, Volume III: Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, and Others. Edited and translated by David A. Campbell. Loeb Classical Library 476. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Virgil, Aeneid. Translated by Frederick Ahl: Oxford University Press, 2007.

External links

| Look up scylla in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scylla. |

- Theoi Project, Skylla – references in classical literature and ancient art.

- Images of Scylla on Classical artefacts (Archive.org link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 519.