Armenian alphabet

The Armenian alphabet (Armenian: Հայոց գրեր, Hayots' grer or Հայոց այբուբեն, Hayots' aybuben; Eastern Armenian: [haˈjotsʰ ajbuˈbɛn]; Western Armenian: [haˈjotsʰ ajpʰuˈpʰɛn]) is an alphabetic writing system used to write Armenian. It was developed around 405 AD by Mesrop Mashtots, an Armenian linguist and ecclesiastical leader. The system originally had 36 letters; eventually, three more were adopted. The alphabet was also in wide use in the Ottoman Empire around the 18th and 19th centuries.

| Armenian alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Armenian |

| Creator | Mesrop Mashtots |

Time period | 405 to present[1] |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Caucasian Albanian[3] |

Sister systems | Latin Coptic Georgian Cyrillic |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Armn, 230 |

Unicode alias | Armenian |

Unicode range |

|

The Armenian word for "alphabet" is այբուբեն (aybuben), named after the first two letters of the Armenian alphabet: ⟨Ա⟩ Armenian: այբ ayb and ⟨Բ⟩ Armenian: բեն ben. Armenian is written horizontally, left-to-right.[4]

Alphabet

Alphabet

| Forms | Name | Letter | Numerical value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Reformed | Pronunciation | Pronunciation | Transliteration | |||||||

| Classical | Eastern | Western | Classical | Eastern | Western | Classical | ISO 9985 | ||||

| Ա • ա | այբ ayb | /ɑjb/ | /ɑjpʰ/ | /ɑ/ | a | 1 | |||||

| Բ • բ | բեն ben | /bɛn/ | /pʰɛn/ | /b/ | /pʰ/ | b | 2 | ||||

| Գ • գ | գիմ gim | /ɡim/ | /kʰim/ | /ɡ/ | /kʰ/ | g | 3 | ||||

| Դ • դ | դա da | /dɑ/ | /tʰɑ/ | /d/ | /tʰ/ | d | 4 | ||||

| Ե • ե | եչ yeč | /jɛtʃʰ/ | /ɛ/, word-initially /jɛ/6 | e | 5 | ||||||

| Զ • զ | զա za | /zɑ/ | /z/ | z | 6 | ||||||

| Է • է | է ē1 | /ɛː/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛː/ | /ɛ/ | ē | 7 | ||||

| Ը • ը7 | ըթ ët' | /ətʰ/ | /ə/ | ə | ë | 8 | |||||

| Թ • թ | թօ t'ò[5] | թո t'o | /tʰo/ | /tʰ/ | tʿ | t’ | 9 | ||||

| Ժ • ժ | ժէ žē | ժե že | /ʒɛː/ | /ʒɛ/ | /ʒ/ | ž | 10 | ||||

| Ի • ի | ինի ini | /ini/ | /i/ | i | 20 | ||||||

| Լ • լ | լիւն liwn | լյուն lyown | /lʏn/ | /ljun/ | /lʏn/ | /l/ | l | 30 | |||

| Խ • խ | խէ xē | խե xe | /χɛː/ | /χɛ/ | /χ/ | x | 40 | ||||

| Ծ • ծ | ծա ça | /tsɑ/ | /dzɑ/ | /ts/ | /dz/ | c | ç | 50 | |||

| Կ • կ | կեն ken | /kɛn/ | /ɡɛn/ | /k/ | /ɡ/ | k | 60 | ||||

| Հ • հ | հօ hò[5] | հո ho | /ho/ | /h/ | h | 70 | |||||

| Ձ • ձ | ձա ja | /dzɑ/ | /tsʰɑ/ | /dz/ | /tsʰ/ | j | 80 | ||||

| Ղ • ղ | ղատ ġat | /ɫɑt/ | /ʁɑt/ | /ʁɑd/ | /ɫ/ | /ʁ/ | ł | ġ | 90 | ||

| Ճ • ճ | ճէ č̣ē | ճե č̣e | /tʃɛː/ | /tʃɛ/ | /dʒɛ/ | /tʃ/ | /dʒ/ | č | č̣ | 100 | |

| Մ • մ | մեն men | /mɛn/ | /m/ | m | 200 | ||||||

| Յ • յ | յի yi | հի hi | /ji/ | /hi/ | /j/ | /h/1, /j/ | y | 300 | |||

| Ն • ն | նու now | /nu/ | /n/, /ŋ/ | n | 400 | ||||||

| Շ • շ | շա ša | /ʃɑ/ | /ʃ/ | š | 500 | ||||||

| Ո • ո | ո vo | /ɔ/ | /ʋɔ/ | /ɔ/, word-initially /ʋɔ/2 | o | 600 | |||||

| Չ • չ | չա ča | /tʃʰɑ/ | /tʃʰ/ | čʿ | č | 700 | |||||

| Պ • պ | պէ pē | պե pe | /pɛː/ | /pɛ/ | /bɛ/ | /p/ | /b/ | p | 800 | ||

| Ջ • ջ | ջէ ǰē | ջե ǰe | /dʒɛː/ | /dʒɛ/ | /tʃʰɛ/ | /dʒ/ | /tʃʰ/ | ǰ | 900 | ||

| Ռ • ռ | ռա ṙa | /rɑ/ | /ɾɑ/ | /r/ | /ɾ/ | ṙ | 1000 | ||||

| Ս • ս | սէ sē | սե se | /sɛː/ | /sɛ/ | /s/ | s | 2000 | ||||

| Վ • վ | վեւ vew | վեվ vev | /vɛv/ | /v/ | v | 3000 | |||||

| Տ • տ | տիւն tiwn | տյուն tyown | /tʏn/ | /tjun/ | /dʏn/ | /t/ | /d/ | t | 4000 | ||

| Ր • ր | րէ rē | րե re | /ɹɛː/ | /ɾɛ/3 | /ɹ/ | /ɾ/3 | r | 5000 | |||

| Ց • ց | ցօ c'ò[5] | ցո c'o | /tsʰo/ | /tsʰ/ | cʿ | c’ | 6000 | ||||

| Ւ • ւ | հիւն hiwn | վյուն vyun5 | /hʏn/ | /w/ | /v/5 | w | 7000 | ||||

| Փ • փ | փիւր p'iwr | փյուր p'yowr | /pʰʏɹ/ | /pʰjuɾ/ | /pʰʏɾ/ | /pʰ/ | pʿ | p’ | 8000 | ||

| Ք • ք | քէ k'ē | քե k'e | /kʰɛː/ | /kʰɛ/ | /kʰ/ | kʿ | k’ | 9000 | |||

| Օ • օ | օ ò1 | — | /o/ | — | /o/ | ō | ò | — | |||

| Ֆ • ֆ | ֆէ fē | ֆե fe | — | /fɛ/ | — | /f/ | f | — | |||

| ու | ու4 ow | — | /u/ | — | /u/ | u | — | ||||

| և | և48 jew | — | /jɛv/ | — | /ɛv/, word-initially /jɛv/ | ew | — | ||||

- Listen to the pronunciation of the letters in

Notes:

- ^ Primarily used in classical orthography; after the reform used word-initially and in some compound words.

- ^ Except in ով /ov/ "who" and ովքեր /ovkʰer/ "those (people)" in Eastern Armenian.

- ^ Iranian Armenians (who speak a subbranch of Eastern Armenian) pronounce this letter as [ɹ], like in Classical Armenian.

- ^ In classical orthography, ու and և are considered a digraph (ո + ւ) and a ligature (ե + ւ), respectively. In reformed orthography, they are separate letters of the alphabet.

- ^ In reformed orthography, the letter ւ appears only as a component of ու. In classical orthography, the letter usually represents /v/, except in the digraph իւ /ju/. The spelling reform in Soviet Armenia replaced իւ with the trigraph յու.

- ^ Except in the present tense of "to be": եմ /em/ "I am", ես /es/ "you are (sing.)", ենք /enkʰ/ "we are", եք /ekʰ/ "you are (pl.)", են /en/ "they are".

- ^ The letter ը is generally used only at the start or end of a word, and so the sound /ə/ is unwritten between consonants.

- ^ The ligature և has no majuscule form; when capitalized it is written as two letters Եւ (classical) or Եվ (reformed).

Ligatures

Ancient Armenian manuscripts used many ligatures. Some of the commonly used ligatures are: ﬓ (մ+ն), ﬔ (մ+ե), ﬕ (մ+ի), ﬖ (վ+ն), ﬗ (մ+խ), և (ե+ւ), etc. Armenian print typefaces also include many ligatures. In the new orthography, the character և is no longer a typographical ligature, but a distinct letter, placed in the new alphabetic sequence, before "o".

Punctuation

Armenian punctuation marks include:

- [ « » ] The čakertner are used as ordinary quotation marks and they are placed like French guillemets: just above the baseline (preferably vertically centered in the middle of the x-height of Armenian lowercase letters. The computer-induced use of English-style single or double quotes (vertical, diagonal or curly forms, placed above the baseline near the M-height of uppercase or tall lowercase letters and at the same level as accents) is strongly discouraged in Armenian as they look too much like other – unrelated – Armenian punctuations.

- [ , ] The storaket is used as a comma, and placed as in English.

- [ ՝ ] The boot' (which looks like a comma-shaped reversed apostrophe) is used as a short stop, and placed in the same manner as the semicolon, to indicate a pause that is longer than that of a comma, but shorter than that of a colon; in many texts it is replaced by the single opening single quote (a 6-shaped, or mirrored 9-shaped, or descending-wedge-shaped elevated comma), or by a spacing grave accent.

- [ ․ ] The mijaket (whose single dot on the baseline looks like a Latin full stop) is used like an ordinary colon, mainly to separate two closely related (but still independent) clauses, or when a long list of items follows.

- [ ։ ] The verjaket (whose vertically stacked two dots look like a Latin colon) is used as the ordinary full stop, and placed at the end of the sentence (many texts in Armenian replace the verjaket by the Latin colon as the difference is almost invisible at low resolution for normal texts, but the difference may be visible in headings and titles as the dots are often thicker to match the same optical weight as vertical strokes of letters, the dots filling the common x-height of Armenian letters).

Armenian punctuation marks used inside a word:

- [ ֊ ] The yent'amna is used as the ordinary Armenian hyphen.

- [ ՟ ] The pativ was used as an Armenian abbreviation mark, and was placed on top of an abbreviated word to indicate that it was abbreviated. It is now obsolete.

- [ ՚ ] The apat'arts is used as a spacing apostrophe (which looks either like a vertical stick or wedge pointing down, or as an elevated 9-shaped comma, or as a small superscript left-to-right closing parenthesis or half ring), only in Western Armenian, to indicate elision of a vowel, usually /ə/.

The following Armenian punctuation marks placed above and slightly to the right of the vowel whose tone is modified, in order to reflect intonation:

- [ ՜ ] The yerkaratsman nshan (which looks like a diagonally rising tilde) is used as an exclamation mark.

- [ ՛ ] The shesht (which looks like a non-spacing acute accent) is used as an emphasis mark.

- [ ՞ ] The hartsakan nshan is used as a question mark.

Transliteration

ISO 9985 (1996) transliterates the Armenian alphabet for modern Armenian as follows:

| ա | բ | գ | դ | ե | զ | է | ը | թ | ժ | ի | լ | խ | ծ | կ | հ | ձ | ղ | ճ | մ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | g | d | je/e | z | e | ë | t’ | ž | i | l | x | ts | k | h | dz | ṙ | tš | m |

| յ | ն | շ | ո | չ | պ | ջ | ռ | ս | վ | տ | ր | ց | ւ | փ | ք | օ | ֆ | ու | և |

| j | n | š | vo/o | tš’ | p | dž | r | s | v | t | r’ | ts’ | w | p’ | k’ | o | f | u | yew/ew |

In the linguistic literature on Classical Armenian, slightly different systems are in use (in particular note that č has a different meaning).

| ա | բ | գ | դ | ե | զ | է | ը | թ | ժ | ի | լ | խ | ծ | կ | հ | ձ | ղ | ճ | մ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | g | d | e | z | ê | ə | t‛ | ž | i | l | x | c | k | h | j | ł | č | m |

| յ | ն | շ | ո | չ | պ | ջ | ռ | ս | վ | տ | ր | ց | ւ | փ | ք | օ | եւ | ու | ֆ |

| y | n | š | o | č‛ | p | ǰ | r̄ | s | v | t | r | c‛ | w | p‛ | k‛ | ô | ev | u | f |

History and development

|

| History of the Armenian language |

|---|

|

|

Armenian alphabet Romanization of Armenian |

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

Hangul 1443 Thaana 18 c. CE (derived from Brahmi numerals) |

Possible antecedents

One of the classical accounts about the existence of an Armenian alphabet before Mashtots comes from Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE – 50 CE), who in his writings notes that the work of the Greek philosopher and historian Metrodorus of Scepsis (ca. 145 BCE – 70 BCE), On Animals, was translated into Armenian. Metrodorus was a close friend and a court historian of the Armenian emperor Tigranes the Great and also wrote his biography. A third century Roman theologian, Hippolytus of Rome (170–235 CE), in his Chronicle, while writing about his contemporary, Emperor Severus Alexander (reigned 208–235 CE), mentions that the Armenians are amongst those nations who have their own distinct alphabet.

Philostratus the Athenian, a sophist of the second and third centuries CE, wrote:

And they say that a leopardess was once caught in Pamphylia which was wearing a chain round its neck, and the chain was of gold, and on it was inscribed in Armenian lettering: "The king Arsaces to the Nysian god".[6]

According to the fifth century Armenian historian Movses of Khoren, Bardesanes of Edessa (154–222 CE), who founded the Gnostic current of the Bardaisanites, went to the Armenian castle of Ani and there read the work of a pre-Christian Armenian priest named Voghyump, written in the Mithraic (Mehean or Mihrean lit. of Mihr or of Mithra – the Armenian national God of Light, Truth and the Sun) script of the Armenian temples in which, amongst other histories, an episode was noted of the Armenian King Tigranes VII (reigned from 144–161, and again 164–186 CE) erecting a monument on the tomb of his brother, the Mithraic High Priest of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia, Mazhan. Movses of Khoren notes that Bardesanes translated this Armenian book into Syriac (Aramaic), and later also into Greek. Another important evidence for the existence of a pre-Mashtotsian alphabet is the fact that the Armenian heathen pantheon included Tir, who was the Patron God of Writing and Science.

A 13th century Armenian historian, Vardan Areveltsi, in his History, notes that during the reign of the Armenian King Leo the Magnificent (reigned 1187–1219), artifacts were found bearing "Armenian inscriptions of the heathen kings of the ancient times". The evidence that the Armenian scholars of the Middle Ages knew about the existence of a pre-Mashtotsian alphabet can also be found in other medieval works, including the first book composed in Mashtotsian alphabet by the pupil of Mashtots, Koriwn, in the first half of the fifth century. Koriwn notes that Mashtots was told of the existence of ancient Armenian letters which he was initially trying to integrate into his own alphabet.[7]

Creation by Mashtots

The Armenian alphabet was introduced by Mesrop Mashtots and Isaac of Armenia (Sahak Partev) in 405 CE. Medieval Armenian sources also claim that Mashtots invented the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets around the same time. However, most scholars link the creation of the Georgian script to the process of Christianization of Iberia, a core Georgian kingdom of Kartli.[8] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,[9] contemporaneously with the Armenian alphabet.[10] Traditionally, the following phrase translated from Solomon's Book of Proverbs is said to be the first sentence to be written down in Armenian by Mashtots:

Ճանաչել զիմաստութիւն եւ զխրատ, իմանալ զբանս հանճարոյ:

Čanačʿel zimastutʿiun yev zxrat, imanal zbans hančaroy.

To know wisdom and instruction; to perceive the words of understanding.— Book of Proverbs, 1:2.

Various scripts have been credited with being the prototype for the Armenian alphabet. Pahlavi was the priestly script in Armenia before the introduction of Christianity, and Syriac, along with Greek, was one of the alphabets of Christian scripture. Armenian shows some similarities to both. However, the general consensus is that Armenian is modeled after the Greek alphabet, supplemented with letters from a different source or sources for Armenian sounds not found in Greek. The evidence for this is: the Greek order of the Armenian alphabet; the ow ligature for the vowel /u/, as in Greek; the letter "ҕ" (tr. I) similar in shape and sound value to cyrillic Ии and (Modern) Greek Ηη; and the shapes of some letters which "seem derived from a variety of cursive Greek".[2] It has been speculated by some scholars in African studies, following Dimitri Olderogge, that the Ge'ez script had an influence on certain letter shapes,[11] but this has not been supported by any experts in Armenian studies.

.jpg)

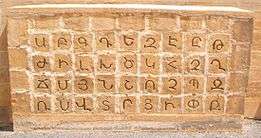

There are four principal calligraphic hands of the script. Erkatagir, or "ironclad letters", seen as Mesrop's original, was used in manuscripts from the 5th to 13th century and is still preferred for epigraphic inscriptions. Bolorgir, or "cursive", was invented in the 10th century and became popular in the 13th. It has been the standard printed form since the 16th century. Notrgir, or "minuscule", invented initially for speed, was extensively used in the Armenian diaspora in the 16th to 18th centuries, and later became popular in printing. Sheghagir, or "slanted writing", is now the most common form.

The earliest known example of the script's usage was a dedicatory inscription over the west door of the church of Saint Sarkis in Tekor. Based on the known individuals mentioned in the inscription, it has been dated to the 480s.[12] The earliest known surviving example of usage outside of Armenia is a mid-6th century mosaic inscription in the chapel of St Polyeuctos in Jerusalem.[13] A papyrus discovered in 1892 at Fayyum and containing Greek words written in Armenian script has been dated on historical grounds to before the Arab conquest of Egypt, i.e. before 640, and on paleographic grounds to the 6th century and perhaps even the late 5th century. It is now in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.[14] The earliest surviving manuscripts written in Armenian using Armenian script date from the 7th–8th century.

Certain shifts in the language were at first not reflected in the orthography. The digraph աւ (au) followed by a consonant used to be pronounced [au] (as in luau) in Classical Armenian, but due to a sound shift it came to be pronounced [o], and has since the 13th century been written օ (ō). For example, classical աւր (awr, [auɹ], "day") became pronounced [oɹ], and is now written օր (ōr). (One word has kept aw, now pronounced /av/: աղաւնի "pigeon", and there are a few proper names still having aw before a consonant: Տաւրոս Taurus, Փաւստոս Faustus, etc.) For this reason, today there are native Armenian words beginning with the letter օ (ō) although this letter was taken from the Greek alphabet to write foreign words beginning with o [o].

The number and order of the letters have changed over time. In the Middle Ages, two new letters (օ [o], ֆ [f]) were introduced in order to better represent foreign sounds; this increased the number of letters from 36 to 38. From 1922 to 1924, Soviet Armenia adopted a reformed spelling of the Armenian language. The reform changed the digraph ու and the ligature և into two new letters, but it generally did not change the pronunciation of individual letters. Those outside of the Soviet sphere (including all Western Armenians as well as Eastern Armenians in Iran) have rejected the reformed spellings, and continue to use the traditional Armenian orthography. They criticize some aspects of the reforms (see the footnotes of the chart) and allege political motives behind them.

Use for other languages

For about 250 years, from the early 18th century until around 1950, more than 2,000 books in the Turkish language were printed using the Armenian alphabet. Not only did Armenians read this Turkish in Armenian script, so did the non-Armenian (including the Ottoman Turkish) elite. An American correspondent in Marash in 1864 calls the alphabet "Armeno-Turkish", describing it as consisting of 31 Armenian letters and "infinitely superior" to the Arabic or Greek alphabets for rendering Turkish.[15] This Armenian script was used alongside the Arabic script on official documents of the Ottoman Empire written in Ottoman Turkish. For instance, the first novel to be written in Turkish in the Ottoman Empire was Vartan Pasha's 1851 Akabi Hikayesi, written in the Armenian script. When the Armenian Duzian family managed the Ottoman mint during the reign of Abdülmecid I, they kept records in Armenian script but in the Turkish language. From the middle of the 19th century, the Armenian alphabet was also used for books written in the Kurdish language in the Ottoman Empire.

The Armenian script was also used by Turkish-speaking assimilated Armenians between the 1840s and 1890s. Constantinople was the main center of Armenian-scripted Turkish press. This portion of the Armenian press declined in the early twentieth century but continued until the Armenian Genocide of 1915.[16]

In areas inhabited by both Armenians and Assyrians, Syriac texts were occasionally written in the Armenian script, although the opposite phenomenon, Armenian texts written in Serto, the Western Syriac script, is more common.[17]

The Kipchak-speaking Armenian Christians of Podolia and Galicia used an Armenian alphabet to produce an extensive amount of literature between 1524 and 1669.[18]

The Armenian script, along with the Georgian, was used by the poet Sayat-Nova in his Armenian poems.[19]

An Armenian alphabet was an official script for the Kurdish language in 1921–1928 in Soviet Armenia.[20]

Character encodings

The Armenian alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in version 1.0, in October 1991. It is assigned the range U+0530–058F. Five Armenian ligatures are encoded in the "Alphabetic presentation forms" block (code point range U+FB13–FB17).

On 15 June 2011, the Unicode Technical Committee (UTC) accepted the Armenian dram sign for inclusion in the future versions of the Unicode Standard and assigned a code for the sign – U+058F (֏). In 2012 the sign was finally adopted in the Armenian block of ISO and Unicode international standards.[21]

The Armenian eternity sign, since 2013, a designated point in Unicode U+058D (֍ – RIGHT-FACING ARMENIAN ETERNITY SIGN) and another for its left-facing variant: U+058E (֎ – LEFT-FACING ARMENIAN ETERNITY SIGN).[22]

| Armenian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+053x | Ա | Բ | Գ | Դ | Ե | Զ | Է | Ը | Թ | Ժ | Ի | Լ | Խ | Ծ | Կ | |

| U+054x | Հ | Ձ | Ղ | Ճ | Մ | Յ | Ն | Շ | Ո | Չ | Պ | Ջ | Ռ | Ս | Վ | Տ |

| U+055x | Ր | Ց | Ւ | Փ | Ք | Օ | Ֆ | ՙ | ՚ | ՛ | ՜ | ՝ | ՞ | ՟ | ||

| U+056x | ՠ | ա | բ | գ | դ | ե | զ | է | ը | թ | ժ | ի | լ | խ | ծ | կ |

| U+057x | հ | ձ | ղ | ճ | մ | յ | ն | շ | ո | չ | պ | ջ | ռ | ս | վ | տ |

| U+058x | ր | ց | ւ | փ | ք | օ | ֆ | և | ֈ | ։ | ֊ | ֍ | ֎ | ֏ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Armenian subset of Alphabetic Presentation Forms[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+FB1x | ﬓ | ﬔ | ﬕ | ﬖ | ﬗ | (U+FB00–FB12, U+FB18–FB4F omitted) | ||||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Legacy

ArmSCII

ArmSCII is a character encoding developed between 1991 and 1999. ArmSCII was popular on the Windows 9x operating systems. With the development of the Unicode standard and its availability on modern operating systems, it has been rendered obsolete.

Arasan-compatible

Arasan-compatible fonts are based on the encoding of the original Arasan font by Hrant Papazian (he started encoding in use since 1986), which simply replaces the Latin characters (among others) of the ASCII encoding with Armenian ones. For example, the ASCII code for the Latin character ⟨A⟩ (65) represents the Armenian character ⟨Ա⟩.

While Arasan-compatible fonts were popular among many users on Windows 9x, the encoding has been deprecated by the Unicode standard.

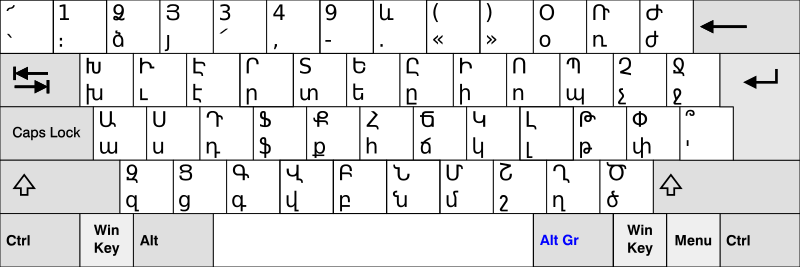

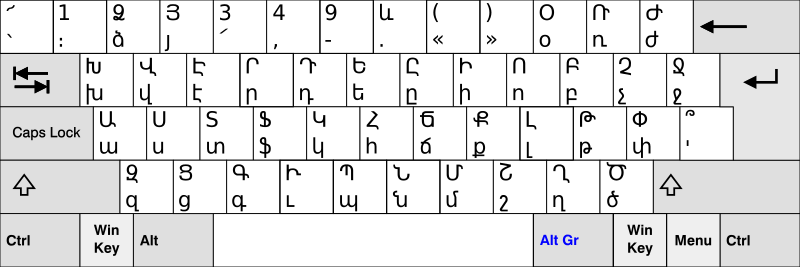

Keyboard layouts

The standard Eastern and Western Armenian keyboards are based on the layout of the font Arasan. These keyboard layouts are mostly phonetic, and allow direct access to every character in the alphabet. Because there are more characters in the Armenian alphabet (39) than in Latin (26), some Armenian characters appear on non-alphabetic keys on a conventional QWERTY keyboard (for example, շ maps to ,).

See also

- Armenian braille

- Armenian calendar

- Armenian numerals

- ArmSCII (single-byte encodings of the Armenian alphabet, also discusses ISO 10585 and the mapping to Unicode)

- Classical Armenian orthography

- Reformed Armenian orthography

- Romanization of Armenian (includes ISO 9985)

References

- Theo Maarten van Lint. From Reciting to Writing and Interpretation: Tendencies, Themes, and Demarcations of Armenian Historical Writing // The Oxford History of Historical Writing: 400–1400 / Edited by Sarah Foot and Chase F. Robinson. — Oxford University Press, 2012. — Vol. 2. — P. 180

- Avedis Sanjian, "The Armenian Alphabet". In Daniels & Bright, The World's Writing Systems, 1996:356–357

- Special internet edition of the article «The script of the Caucasian Albanians in the light of the Sinai palimpsests» by Jost Gippert (2011) // Original edition in Die Entstehung der kaukasischen Alphabete als kulturhistorisches Phänomen / The Creation of the Caucasian Alphabets as Phenomenon of Cultural History. Referate des Internationalen Symposiums (Wien, 1.-4. Dezember 2005), ed. by Werner Seibt and Johannes Preiser-Kapeller. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 2011

- Simon Ager (2010). "Armenian alphabet". Omniglot: writing systems & languages of the world. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- Melkonian, Zareh (1990). Գործնական Քերականութիւն — Արդի Հայերէն Լեզուի (Միջին եւ Բարձրագոյն Դասընթացք) (in Armenian) (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles. p. 6.

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Book II, Chapter II, pp. 120–121, tr. by F. C. Conybeare, 1912

- "ԳԻՐՔ". Scribd.

- B. G. Hewitt (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Hewitt, p. 4

- Barbara A. West; Oceania. Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia. p. 230. ISBN 9781438119137.

Archaeological work in the last decade has confirmed that a Georgian alphabet did exist very early in Georgia's history, with the first examples being dated from the fifth century C.E.

- Richard Pankhurst. 1998. The Ethiopians: A History. p25

- Donabedian, Patrick; Thierry, Jean-Michel. "Armenian Art", page584. New York, 1989: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0810906259.

- Nersessian, Vreg. "Treasure From the Ark", p36-37. London, 2001: The British Library.

- Dickran Kouymjian, "Unique Armenian Papyrus", in "Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Armenian Linguistics", 1996, p381-386.

- Andrew T. Pratt, "On the Armeno-Turkish Alphabet", in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 8 (1866), pp. 374–376.

- Kharatian, A. A. (1995). "Հայատառ թուրքերեն մամուլը (1840—1890–ական թթ.) [Armenian periodicals in Turkish letters (1840-1890s)]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (2): 72–85.

- Ester Petrosian, Manuscript Cairo Syriac 11, Matenadaran Bulletin, vol 24, p70.

- (in Russian) Qypchaq languages. Unesco.kz

- Charles Dowsett, E. Peters. Sayat'-Nova. An 18th-century Troubadour: a Biographical and Literary Study. Peeters Publishers, 1997 ISBN 90-6831-795-4; p. xv

- Курдский язык (in Russian). Krugosvet.

...в Армении на основе русского алфавита с 1946 (с 1921 на основе армянской графики, с 1929 на основе латиницы).

- "Unicode 6.1 Versioned Charts Index". unicode.org.

- "ISO/IEC 10646:2012/Amd.1: 2013 (E)" (PDF).

External links

- armenian-alphabet.com - animated interactive handwritten Armenian alphabet.

- Armenotype – site about Armenian typeface design and typography.

- Armenian Apostolic (Orthodox) Church Library Online (in English, Armenian, and Russian)

Information on Armenian character set encoding.

Armenian Phonetic Keyboard Layout

Armenian Transliteration

- English / French script to Armenian Transliteration Hayadar.com – Online, Latin to Armenian transliteration engine.

- Latin-Armenian Transliteration Converts Latin letters into Armenian and vice versa. Supports multiple transliteration tables and spell checking.

- Transliteration schemes for the Armenian alphabet (transliteration.eki.ee)

Armenian Orthography converters

- Nayiri.com (integrated orthography converter: reformed to classical)