West Virginia

West Virginia (/vərˈdʒɪniə/ (![]()

West Virginia | |

|---|---|

| State of West Virginia | |

| Nickname(s): Mountain State | |

| Motto(s): Montani semper liberi (English: Mountaineers Are Always Free) | |

| Anthem: 4 songs | |

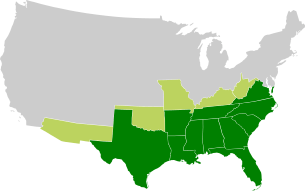

Map of the United States with West Virginia highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Part of Virginia |

| Admitted to the Union | June 20, 1863 (35th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Charleston |

| Largest metro | Huntington-Ashland Tri-State Area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jim Justice (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Mitch Carmichael (R) |

| Legislature | West Virginia Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Delegates |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia |

| U.S. senators | Joe Manchin (D) Shelley Moore Capito (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 1: David McKinley (R) 2: Alex Mooney (R) 3: Carol Miller (R) (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 24,230 sq mi (62,755 km2) |

| • Land | 24,078 sq mi (62,361 km2) |

| • Water | 152 sq mi (394 km2) 0.6% |

| Area rank | 41st |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 240 mi (385 km) |

| • Width | 130 mi (210 km) |

| Elevation | 1,513 ft (461 m) |

| Highest elevation | 4,863 ft (1,482 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 240 ft (73 m) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 1,792,147 |

| • Rank | 38th |

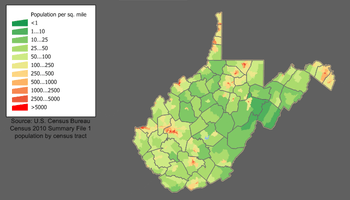

| • Density | 77.1/sq mi (29.8/km2) |

| • Density rank | 29th |

| • Median household income | $43,469[4] |

| • Income rank | 50th |

| Demonym(s) | West Virginian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | De jure: English[5] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | WV |

| ISO 3166 code | US-WV |

| Trad. abbreviation | W.Va. |

| Latitude | 37°12′ N to 40°39′ N |

| Longitude | 77°43′ W to 82°39′ W |

| Website | wv |

| West Virginia state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) |

| Butterfly | Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) |

| Fish | Brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) |

| Flower | Rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum) |

| Insect | Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) |

| Mammal | Black bear (Ursus americanus) |

| Reptile | Timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) |

| Tree | Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Colors | Old gold and blue |

| Food | Golden Delicious apple (Malus domestica) |

| Fossil | Jefferson's ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii) |

| Gemstone | Silicified Mississippian fossil coral (Lithostrotionella) |

| Rock | Coal |

| Slogan | "Wild and Wonderful" "Open for Business" (former) "Almost Heaven" (former) |

| Soil | Monongahela Silt Loam |

| Tartan | West Virginia Shawl |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2005 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

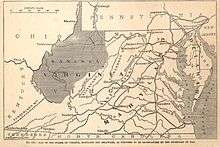

West Virginia became a state following the Wheeling Conventions of 1861, at the start of the American Civil War. Delegates from the Unionist counties of northwestern Virginia decided to break away from Virginia, which also included secessionist counties in the new state.[6] West Virginia was admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863, and was a key border state during the war. It was the only state to form by separating from a Confederate state, the first to separate from any state since Maine separated from Massachusetts, and was one of two states (along with Nevada) admitted to the Union during the American Civil War. While a portion of its residents held slaves, most of the residents were yeoman farmers, and the delegates provided for gradual abolition of slavery in the new state Constitution and the state's legislature completely abolished slavery before the end of the war.

The northern panhandle extends adjacent to Pennsylvania and Ohio, with the West Virginia cities of Wheeling and Weirton just across the border from the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, while Bluefield is less than 70 miles (110 km) from North Carolina. Huntington in the southwest is close to the states of Ohio and Kentucky, while Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry in the Eastern Panhandle region are considered part of the Washington metropolitan area, in between the states of Maryland and Virginia. The unique position of West Virginia means it is often included in several U.S. geographical regions, including the Mid-Atlantic, the Upland South, and the Southeastern United States. It is the only state that is entirely within the area served by the Appalachian Regional Commission; the area is commonly defined as "Appalachia".[7]

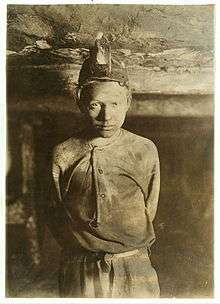

The state is noted for its mountains and rolling hills, its historically significant logging and coal mining industries, and its political and labor history. It is also known for a wide range of outdoor recreational opportunities, including skiing, whitewater rafting, fishing, hiking, backpacking, mountain biking, rock climbing, and hunting.

History

Many ancient man-made earthen mounds from various prehistoric mound builder cultures survive, especially in the areas of present-day Moundsville, South Charleston, and Romney. The artifacts uncovered in these give evidence of village societies. They had a tribal trade system culture that crafted cold-worked copper pieces.

In the 1670s during the Beaver Wars, the powerful Iroquois, five allied nations based in present-day New York and Pennsylvania, drove out other American Indian tribes from the region in order to reserve the upper Ohio Valley as a hunting ground. Siouan language tribes, such as the Moneton, had previously been recorded in the area.

A century later, the area now identified as West Virginia was contested territory among Anglo-Americans as well, with the colonies of Pennsylvania and Virginia claiming territorial rights under their colonial charters to this area before the American Revolutionary War. Some speculative land companies, such as the Vandalia Company,[8] and later the Ohio Company and Indiana Company, tried to legitimize their claims to land in parts of West Virginia and present day Kentucky, but failed. This rivalry resulted in some settlers petitioning the Continental Congress to create a new territory called Westsylvania. With the federal settlement of the Pennsylvania and Virginia border dispute, creating Kentucky County, Virginia, Kentuckians "were satisfied [...] and the inhabitants of a large part of West Virginia were grateful."[9]

The Crown considered the area of West Virginia to be part of the British Virginia Colony from 1607 to 1776. The United States considered this area to be the western part of the state of Virginia (which was commonly referred as Trans-Allegheny Virginia) from 1776 to 1863, before the formation of West Virginia. Its residents were discontented for years with their position in Virginia, as the government was dominated by the planter elite of the Tidewater and Piedmont areas. The legislature had electoral malapportionment, based on the counting of slaves toward regional populations, and the western white residents were underrepresented in the state legislature. More subsistence and yeoman farmers lived in the west and they were generally less supportive of slavery, although many counties were divided on their support. The residents of this area became more sharply divided after the planter elite of eastern Virginia voted to secede from the Union during the Civil War.

Residents of the western and northern counties set up a separate government under Francis Pierpont in 1861, which they called the Restored Government. Most voted to separate from Virginia, and the new state was admitted to the Union in 1863. In 1864 a state constitutional convention drafted a constitution, which was ratified by the legislature without putting it to popular vote. West Virginia abolished slavery by a gradual process and temporarily disenfranchised men who had held Confederate office or fought for the Confederacy.

West Virginia's history has been profoundly affected by its mountainous terrain, numerous and vast river valleys, and rich natural resources. These were all factors driving its economy and the lifestyles of its residents, who tended to live in many small, relatively isolated communities in the mountain valleys.

Prehistory

A 2010 analysis of a local stalagmite revealed that Native Americans were burning forests to clear land as early as 100 BCE.[10] Some regional late-prehistoric Eastern Woodland tribes were more involved in hunting and fishing, practicing the Eastern Agricultural Complex gardening method which used fire to clear out underbrush from certain areas. Another group progressed to the more time-consuming, advanced companion crop fields method of gardening. Also continuing from ancient indigenous people of the state, they cultivated tobacco through to early historic times. It was used in numerous social and religious rituals.

"Maize (corn) did not make a substantial contribution to the diet until after 1150 BP", to quote Mills (OSU 2003). Eventually, tribal villages began depending on corn to feed their turkey flocks, as Kanawha Fort Ancients practiced bird husbandry. The local Indians made corn bread and a flat rye bread called "bannock" as they emerged from the protohistoric era. A horizon extending from a little before the early 18th century is sometimes called the acculturating Fireside Cabin culture. Trading posts were established by European traders along the Potomac and James rivers.

Tribes that inhabited West Virginia as of 1600 were the Siouan Monongahela Culture to the north, the Fort Ancient culture along the Ohio River from the Monongahela to Kentucky and extending an unknown distance inland,[11] and the Eastern Siouan Tutelo and Moneton tribes in the southeast. There was also the Iroquoian Susquehannock in the region approximately east of the Monongahela River and north of the Monongahela National Forest, a possible tribe called the Senandoa, or Shenandoah, in the Shenandoah Valley and the easternmost tip of the state may have been home to the Manahoac people. The Monongahela may have been the same as a people known as the Calicua, or Cali.[12] The following may have also all been the same tribe—Moneton, Moheton, Senandoa, Tomahitan.

During the Beaver Wars, other tribes moved into the region. There was the Iroquoian Tiontatecaga (also Little Mingo, Guyandotte),[13] who seem to have split off from the Petun after they were defeated by the Iroquois. They eventually settled somewhere between the Kanawha and Little Kanawha Rivers. During the 1750s, when the Mingo Seneca seceded from the Iroquois and returned to the Ohio River Valley, they contend that this tribe merged with them. The Shawnee arrived as well, but were primarily stationed within former Monongahela territory approximately until 1750, however they did extend their influence throughout the Ohio River region. They were the last Native tribe of West Virginia and were driven out by the United States during the Shawnee Wars (1811–1813). The Erie, who were chased out of Ohio around 1655, are now believed to be the same as the Westo, who invaded as far as South Carolina before being destroyed in the 1680s. If so, their path would have brought them through West Virginia. The historical movement of the Tutelo,[14] as well as Carbon dating for the Fort Ancients seem to correspond with the given period of 1655–1670 as the time of their removal.[11] The Susquehannocks were original participants of the Beaver Wars, but were cut off from the Ohio River by the Iroquois around 1630 and found themselves in dire straits. From disease, constant warfare and an inability to provide for themselves financially, they began to collapse and moved further and further east, to the Susquehanna River of Eastern Pennsylvania.[15] The Manahoac were probably forced out in the 1680s, when the Iroquois began to invade Virginia.[16] The Siouan tribes there moved into North Carolina and later returned as one tribe, known as the Eastern Blackfoot, or Christannas.[17]

The Westo did not secure the territory they conquered. Before they were even gone, displaced natives from the south flooded into freshly conquered regions and took them over.[18] These became known as the Shattaras, or West Virginia Cherokees. They took in and merged with the Monetons, who began to refer to themselves as the Mohetons. The Calicua also began to refer to themselves as Cherokees soon after, showing an apparent further merger. These Shattaras were closely related to the tribes which formed to the south in the aftermath of the Westo—the Yuchi and Cherokee. From 1715–1717, the Yamasee War sprang up. The Senandoa allegedly sided with the Yuchi and were destroyed by Yamasee allies.[19] Therefore, if the Senandoa were the same tribe as the Moneton, this would mean the collapse of Shattara-Moneton culture. Another tribe who appeared in the region were the Canaragay, or Kanawha.[20] They later migrated to Maryland and merged into colonial culture.

European exploration and settlement

In 1671, General Abraham Wood, at the direction of Royal Governor William Berkeley of the Virginia Colony, sent a party from Fort Henry led by Thomas Batts and Robert Fallam to survey this territory. They were the first Europeans recorded as discovering Kanawha Falls. Some sources state that Governor Alexander Spotswood's 1716 Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition (for which the state's Golden Horseshoe Competition for 8th graders was named) had penetrated as far as Pendleton County; however, modern historians interpret the original accounts of the excursion as suggesting that none of the expedition's horsemen ventured much farther west of the Blue Ridge Mountains than Harrisonburg, Virginia. John Van Metre, an Indian trader, penetrated into the northern portion in 1725. The same year, German settlers from Pennsylvania founded New Mecklenburg, the present Shepherdstown, on the Potomac River, and others followed.[21]

King Charles II of England, in 1661, granted to a company of gentlemen the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, known as the Northern Neck. Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron ultimately took possession of this grant, and in 1746, a stone was erected at the source of the North Branch Potomac River to mark the western limit of his grant. A considerable part of this land was surveyed by the young George Washington between 1748 and 1751. The diary kept by Washington recorded that there were already many squatters, largely of German origin, along the South Branch Potomac River.[22]

Christopher Gist, a surveyor in the employ of the first Ohio Company, which was composed chiefly of Virginians, explored the country along the Ohio River north of the mouth of the Kanawha River between 1751 and 1752. The company sought to have a fourteenth colony established with the name "Vandalia". Many settlers crossed the mountains after 1750, though they were hindered by Native American resistance. Few Native Americans lived permanently within the present limits of the state, but the region was a common hunting ground, crossed by many trails. During the French and Indian War (the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe), Indian allies of the French nearly destroyed the scattered British settlements.[23]

Shortly before the American Revolutionary War, in 1774 the Crown Governor of Virginia John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, led a force over the mountains. A body of militia under then-Colonel Andrew Lewis dealt the Shawnee Indians, under Hokoleskwa (or "Cornstalk"), a crushing blow during the Battle of Point Pleasant at the junction of the Kanawha and the Ohio rivers.[23] At the Treaty of Camp Charlotte concluding Dunmore's War, Cornstalk agreed to recognize the Ohio River as the new boundary with the "Long Knives". By 1776, however, the Shawnee had returned to war, joining the Chickamauga, a band of Cherokee known for the area where they lived. Native American attacks on settlers continued until after the American Revolutionary War. During the war, the settlers in western Virginia were generally active Whigs and many served in the Continental Army.[23] However, Claypool's Rebellion of 1780–1781, in which a group of men refused to pay taxes imposed by the Continental Army, showed war-weariness in what became West Virginia.

Trans-Allegheny Virginia

Social conditions in western Virginia were entirely unlike those in the eastern portion of the state. The population was not homogeneous, as a considerable part of the immigration came by way of Pennsylvania and included Germans, Protestant Scotch-Irish, and settlers from the states farther north. Counties in the east and south were settled mostly by eastern Virginians. During the American Revolution, the movement to create a state beyond the Alleghenies was revived and a petition for the establishment of "Westsylvania" was presented to Congress, on the grounds that the mountains presented an almost impassable barrier to the east. The rugged nature of the country made slavery unprofitable, and time only increased the social, political, economic, and cultural differences (see Tuckahoe-Cohee) between the two sections of Virginia.[23]

In 1829, a constitutional convention met in Richmond to consider reforms to Virginia's outdated constitution. Philip Doddridge of Brooke County championed the cause of western Virginians who sought a more democratic frame of government.[24] However, western reforms were rejected by leaders from east of the Alleghenies who "clung to political power in an effort to preserve their plantation lifestyles dependent on enslaving blacks".[25] Virginia leaders maintained a property qualification for suffrage effectively disenfranchising poorer farmers in the west whose families did much of the farm-work themselves. In addition, the 1829–1830 convention gave the slave-holding counties the benefit of three-fifths of their slave population in apportioning the state's representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. As a result, every county west of the Alleghenies except one voted to reject the constitution, which nevertheless passed because of eastern support.[23] Failure of the eastern planter elite to make constitutional reforms exacerbated existing east–west sectionalism in Virginia and contributed to Virginia's later division.[26]

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850–51, the Reform Convention, addressed a number of issues important to western Virginians. It extended the vote to all white males 21 years or older. The governor, lieutenant governor, the judiciary, sheriffs, and other county officers were to be elected by public vote. The composition of the General Assembly was changed. Representation in the house of delegates was apportioned on the basis of the census of 1850, counting whites only. The Senate representation was arbitrarily fixed at 50 seats, with the west receiving twenty, and the east thirty senators. This was made acceptable to the west by a provision that required the General Assembly to reapportion representation on the basis of white population in 1865, or else put the matter to a public referendum. But the east also gave itself a tax advantage in requiring a property tax at true and actual value, except for slaves. Slaves under the age of 12 years were not taxed and slaves over that age were taxed at only $300, a fraction of their true value. Small farmers, however, had all their assets, animals, and land taxed at full value. Despite this tax and the lack of internal improvements in the west, the vote was 75,748 for and 11,063 against the new Constitution. Most of the opposition came from delegates from eastern counties, who did not like the compromises made for the west.[27]

Given these differences, many in the west had long contemplated a separate state. In particular, men such as lawyer Francis H. Pierpont from Fairmont, had long chafed under the political domination of the Tidewater and Piedmont slave-holders. In addition to differences over the abolition of slavery, he and allies felt the Virginia government ignored and refused to spend funds on needed internal improvements in the west, such as turnpikes and railroads.[28]

Separation from Virginia

West Virginia was the only state in the Union to separate from a Confederate state (Virginia) during the American Civil War.[30] In Richmond on April 17, 1861, the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 voted to secede from the Union, but of the 49 delegates from the northwestern corner (which ultimately became West Virginia) only 17 voted in favor of the Ordinance of Secession, while 30 voted against[31] (with two abstentions).[32] Almost immediately after that vote, a mass meeting at Clarksburg recommended that each county in northwestern Virginia send delegates to a convention to meet in Wheeling on May 13, 1861. When this First Wheeling Convention met, 425 delegates from 25 counties were present, though more than one-third of the delegates were from the northern panhandle area.[33] Soon, there was a division of sentiment.[23]

Some delegates led by John S. Carlile favored the immediate formation of a new state, while others led by Waitman Willey argued that, as Virginia's secession had not yet been passed by the required referendum (as happened on May 23), such action would constitute revolution against the United States.[34] The convention decided that if Virginians adopted the secession ordinance (of which there was little doubt), another convention including the members-elect of the legislature would meet in Wheeling in June 1861. On May 23, 1861, secession was ratified by a large majority in Virginia as a whole, but in the western counties 34,677 voted against and 19,121 voted for the Ordinance.[35]

The Second Wheeling Convention met as agreed on June 11 and declared that, since the Secession Convention had been called without popular consent, all its acts were void and that all who adhered to it had vacated their offices.[23] The Wheeling Conventions, and the delegates themselves, were never actually elected by public ballot to act on behalf of western Virginia.[36] Of its 103 members, 33 had been elected to the Virginia General Assembly[37] on May 23. This included some hold-over state senators whose four-year terms had begun in 1859, and some who vacated their offices to convene in Wheeling. Other members "were chosen even more irregularly—some in mass meetings, others by county committee, and still others were seemingly self-appointed".[38] An act for the reorganization of the government was passed on June 19. The next day convention delegates chose Francis H. Pierpont as governor of Virginia, and elected other officers to a rival state government and two U.S. senators (Willey and Carlile) to replace secessionists before adjourning. The federal government in Washington, D.C. promptly recognized the new government and seated the two new senators. Thus, there were two state governments in Virginia: one pledging allegiance to the United States and one to the Confederacy.[23]

The second Wheeling Convention had recessed until August 6, then reassembled on August 20 and called for a popular vote on the formation of a new state and for a convention to frame a constitution if the vote should be favorable. At the October 24, 1861 election, 18,408 votes were cast for the new state and only 781 against.[23] The election results were questioned, since the Union army then occupied the area and Union troops were stationed at many of the polls to prevent Confederate sympathizers from voting.[39] This was also election day for local offices, and elections were also held in camps of Confederate soldiers, who elected rival state officials, such as Robert E. Cowan. Most pro-statehood votes came from 16 counties around the Northern panhandle.[40] Over 50,000 votes had been cast on the Ordinance of Secession, yet the vote on statehood garnered little more than 19,000.[41] In Ohio County, home to Wheeling, only about a fourth of the registered voters cast votes.[42] In most of what would become West Virginia, there was no vote at all, as two-thirds of the territory of West Virginia had voted for secession and county officers remained loyal to Richmond. Votes recorded from pro-secession counties were mostly cast elsewhere by Unionist refugees from these counties.[43]

Despite that controversy, delegates (including many Methodist ministers) met to write a new Constitution for the new state, beginning on November 26, 1861. During that constitutional convention, a Mr. Lamb of Ohio County and a Mr. Carskadon claimed that in Hampshire County, out of 195 votes only 39 were cast by citizens of the state; the rest were cast illegally by Union soldiers.[44] One of the key figures was Rev. Gordon Battelle, who also represented Ohio County, and who proposed resolutions to establish public schools, as well as to limit movement of slaves into the new state, and to gradually abolish slavery. The education proposal succeeded, but the convention tabled the slavery proposals before finishing its work on February 18, 1862. The new constitution was more closely modeled on that of Ohio than of Virginia, adopting a township model of government rather than the "courthouse cliques" of Virginia which Carlile criticized, and a compromise demanded by the Kanawha region (Charleston lawyers Benjamin Smith and Brown) allowed counties and municipalities to vote subsidies for railroads or other improvement organizations.[45] The resulting instrument was ratified (18,162 for and 514 against) on April 11, 1862.

On May 13, 1862 the state legislature of the reorganized government approved the formation of the new state. An application for admission to the Union was made to Congress, introduced by Senator Waitman Willey of the Restored Government of Virginia. However, Sen. Carlile sought to sabotage the bill, first trying to expand the new state's boundaries to include the Shenandoah Valley, and then to defeat the Willey amendment at home.[46] On December 31, 1862, an enabling act was approved by President Abraham Lincoln admitting West Virginia, on the condition that a provision for the gradual abolition of slavery be inserted in its constitution[23] (as Rev. Battelle had urged in the Wheeling Intelligencer and also written to Lincoln). While many felt West Virginia's admission as a state was both illegal and unconstitutional, Lincoln issued his Opinion on the Admission of West Virginia finding that "the body which consents to the admission of West Virginia is the Legislature of Virginia", and that its admission was therefore both constitutional and expedient.[47]

The convention was reconvened on February 12, 1863, and the abolition demand of the federal enabling act was met. The revised constitution was adopted on March 26, 1863 and on April 20, 1863, President Lincoln issued a proclamation admitting the state 60 days later on June 20, 1863. Meanwhile, officers for the new state were chosen, while Gov. Pierpont moved his pro-Union Virginia capital to Union-occupied Alexandria, where he asserted and exercised jurisdiction over all the remaining Virginia counties within the federal lines.[23]

The question of the constitutionality of the formation of the new state was later brought before the Supreme Court of the United States in Virginia v. West Virginia. Berkeley and Jefferson counties lying on the Potomac east of the mountains, in 1863, with the consent of the reorganized government of Virginia voted in favor of annexation to West Virginia.[23]

Many voters of the strongly pro-secessionist counties were absent in the Confederate Army when the vote was taken and refused to acknowledge the transfer when they returned. The Virginia General Assembly repealed the act of secession and, in 1866, brought suit against West Virginia asking the court to declare the counties a part of Virginia, which would have declared West Virginia's admission as a state unconstitutional. Meanwhile, on March 10, 1866, Congress passed a joint resolution recognizing the transfer.[23] The Supreme Court decided in favor of West Virginia in 1870.[48]

During the Civil War, Union General George B. McClellan's forces gained possession of the greater part of the territory in the summer of 1861, culminating at the Battle of Rich Mountain, and Union control was never again seriously threatened. In 1863, General John D. Imboden, with 5,000 Confederates, raided a considerable portion of the state and burned Pierpont's library, although Senator Willey escaped their grasp. Bands of guerrillas burned and plundered in some sections, and were not entirely suppressed until after the war ended.[23] The Eastern Panhandle counties were more affected by the war, with military control of the area repeatedly changing hands.

The area that became West Virginia actually furnished about an equal number of soldiers to the federal and Confederate armies,[49] approximately 22,000–25,000 each. In 1865, the Wheeling government found it necessary to strip voting rights from returning Confederates in order to retain control. James Ferguson, who proposed the law, said if it was not enacted he would lose election by 500 votes.[50] The property of Confederates might also be confiscated, and in 1866 a constitutional amendment disfranchising all who had given aid and comfort to the Confederacy was adopted. The addition of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution caused a reaction. The Democratic party secured control in 1870, and in 1871, the constitutional amendment of 1866 was abrogated. The first steps toward this change had been taken, however, by the Republicans in 1870. On August 22, 1872, an entirely new constitution was adopted.[23]

Beginning in Reconstruction, and for several decades thereafter, the two states disputed the new state's share of the pre-war Virginia government's debts, which had mostly been incurred to finance public infrastructure improvements, such as canals, roads, and railroads under the Virginia Board of Public Works. Virginians—led by former Confederate general William Mahone—formed a political coalition based upon this: the Readjuster Party. Although West Virginia's first constitution provided for the assumption of a part of the Virginia debt, negotiations opened by Virginia in 1870 were fruitless, and in 1871, Virginia funded two-thirds of the debt and arbitrarily assigned the remainder to West Virginia.[51] The issue was finally settled in 1915, when the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that West Virginia owed Virginia $12,393,929.50.[52] The final instalment of this sum was paid in 1939.

Development of natural resources

After Reconstruction, the new 35th state benefited from the development of its mineral resources more than any other single economic activity.

Saltpeter caves had been employed throughout Appalachia for munitions; the border between West Virginia and Virginia includes the "Saltpeter Trail", a string of limestone caverns containing rich deposits of calcium nitrate which were rendered and sold to the government. The trail stretched from Pendleton County to the western terminus of the route in the town of Union, Monroe County. Nearly half of these caves are on the West Virginia side, including Organ Cave and Haynes Cave. In the late 18th-century, saltpeter miners in Haynes Cave found large animal bones in the deposits. These were sent by a local historian and frontier soldier Colonel John Stuart to Thomas Jefferson. The bones were named Megalonyx jeffersonii, or great-claw, and became known as Jefferson's three-toed sloth. It was declared the official state fossil of West Virginia in 2008. The West Virginia official state rock is bituminous coal,[53] and the official state gemstone is silicified Mississippian fossil Lithostrotionella coral.[54]

The limestone also produced a useful quarry industry, usually small, and softer, high-calcium seams were burned to produce industrial lime. This lime was used for agricultural and construction purposes; for many years a specific portion of the C & O Railroad carried limestone rock to Clifton Forge, Virginia as an industrial flux.

Salt mining had been underway since the 18th century, though it had largely played out by the time of the American Civil War, when the red salt of Kanawha County was a valued commodity of first Confederate, and later Union, forces. In years following, more sophisticated mining methods would restore West Virginia's role as a major producer of salt.

However, in the second half of the 19th century, there was an even greater treasure not yet developed: bituminous coal. It would fuel much of the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. and the steamships of many of the world's navies.

The residents (both Native Americans and early European settlers) had long known of the underlying coal, and that it could be used for heating and fuel. However, for a long time, "personal" or artisanal mining was the only practical development. After the War, with the new railroads came a practical method to transport large quantities of coal to expanding U.S. and export markets. As the anthracite mines of northwestern New Jersey and Pennsylvania began to play out during this same time period, investors and industrialists focused new interest in West Virginia. Geologists such as Dr. David T. Ansted surveyed potential coal fields and invested in land and early mining projects.

The completion of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) across the state to the new city of Huntington on the Ohio River in 1872 opened access to the New River Coal Field. Soon, the C&O was building its huge coal pier at Newport News, Virginia on the large harbor of Hampton Roads. In 1881, the new Philadelphia-based owners of the former Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad (AM&O), which stretched across Virginia's southern tier from Norfolk, had sights clearly set on the Mountain State, where the owners had large land holdings. Their railroad was renamed Norfolk and Western (N&W), and a new railroad city was developed at Roanoke to handle planned expansion. After its new president Frederick J. Kimball and a small party journeyed by horseback and saw firsthand the rich bituminous coal seam, which Kimball's wife named Pocahontas, the N&W redirected its planned westward expansion to reach it. Soon, the N&W was also shipping from new coal piers at Hampton Roads.

In 1889, in the southern part of the state, along the Norfolk and Western rail lines, the important coal center of Bluefield, West Virginia was founded. The "capital" of the Pocahontas coalfield, this city would remain the largest city in the southern portion of the state for several decades. It shares a sister city with the same name, Bluefield, in Virginia.

In the northern portion of the state and elsewhere, the older Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) and other lines also expanded to take advantage of coal opportunities. The B&O developed coal piers in Baltimore and at several points on the Great Lakes. Other significant rail carriers of coal were the Western Maryland Railway (WM), Southern Railway (SOU), and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N).

Particularly notable was a latecomer, the Virginian Railway (VGN). By 1900 only the most rugged terrain of southern West Virginia was any distance from the existing railroads and mining activity. Within this area west of the New River Coalfield in Raleigh and Wyoming counties lay the Winding Gulf Coalfield, later promoted as the "Billion Dollar Coalfield".

A protégé of Dr. Ansted was William Nelson Page (1854–1932), a civil engineer and mining manager in Fayette County. Former West Virginia governor William A. MacCorkle described him as a man who knew the land "as a farmer knows a field". Beginning in 1898, Page teamed with northern and European-based investors to take advantage of the undeveloped area. They acquired large tracts of land in the area, and Page began the Deepwater Railway, a short-line railroad chartered to stretch between the C&O at its line along the Kanawha River and the N&W at Matoaka—a distance of about 80 miles (130 km).

Although the Deepwater plan should have provided a competitive shipping market via either railroad, leaders of the two large railroads did not appreciate the scheme. In secret collusion, each declined to negotiate favorable rates with Page, nor did they offer to purchase his railroad, as they had many other short-lines. However, if the C&O and N&W presidents thought they could thus kill the Page project, they were to be proved mistaken. One of the silent partner investors Page had enlisted was millionaire industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers, a principal in John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Trust and an old hand at developing natural resources and transportation. A master at competitive "warfare", Henry Rogers did not like to lose in his endeavors and also had "deep pockets".

Instead of giving up, Page (and Rogers) quietly planned and then built their tracks all the way east across Virginia, using Rogers' private fortune to finance the $40 million cost. When the renamed Virginian Railway (VGN) was completed in 1909, no fewer than three railroads were shipping ever-increasing volumes of coal to export from Hampton Roads. West Virginia coal was also under high demand at Great Lakes ports. The VGN and the N&W ultimately became parts of the modern Norfolk Southern system, and the VGN's well-engineered 21st-century tracks continue to offer a favorable gradient to Hampton Roads.

As coal mining and related work became major employment activities in the state, there was considerable labor strife as working conditions, safety issues and economic concerns arose. Even in the 21st century, mining safety and ecological concerns is still challenging to the state whose coal continues to power electrical generating plants in many other states.

Coal is not the only valuable mineral found in West Virginia, as the state was the site of the 1928 discovery of the 34.48 carat (6.896 g) Jones Diamond.

Geography

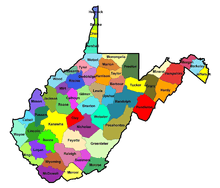

Located in the Appalachian Mountain range, West Virginia covers an area of 24,229.76 square miles (62,754.8 km2), with 24,077.73 square miles (62,361.0 km2) of land and 152.03 square miles (393.8 km2) of water, making it the 41st-largest state in the United States.[55] West Virginia borders Pennsylvania and Maryland in the northeast, Virginia in the southeast, Ohio in the northwest, and Kentucky in the southwest. Its longest border is with Virginia at 381 miles (613 km), followed by Ohio at 243 miles (391 km), Maryland at 174 miles (280 km), Pennsylvania at 118 miles (190 km), and Kentucky at 79 miles (127 km).[56]

Geology and terrain

West Virginia is located entirely within the Appalachian Region, and the state is almost entirely mountainous, giving reason to the nickname The Mountain State and the motto Montani Semper Liberi ("Mountaineers are always free"). The elevations and ruggedness drop near large rivers like the Ohio River or Shenandoah River. About 75% of the state is within the Cumberland Plateau and Allegheny Plateau regions. Though the relief is not high, the plateau region is extremely rugged in most areas. The average elevation of West Virginia is approximately 1,500 feet (460 m) above sea level, which is the highest of any U.S. state east of the Mississippi River.

On the eastern state line with Virginia, high peaks in the Monongahela National Forest region give rise to an island of colder climate and ecosystems similar to those of northern New England and eastern Canada. The highest point in the state is atop Spruce Knob, at 4,863 feet (1,482 m),[57] and is covered in a boreal forest of dense spruce trees at altitudes above 4,000 feet (1,200 m). Spruce Knob lies within the Monongahela National Forest and is a part of the Spruce Knob-Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area.[58] A total of six wilderness areas can also be found within the forest. Outside the forest to the south, the New River Gorge is a canyon 1,000 feet (300 m) deep, carved by the New River. The National Park Service manages a portion of the gorge and river that has been designated as the New River Gorge National River, one of only fifteen rivers in the U.S. with this level of protection.

Other areas under protection and management include:

|

|

Most of West Virginia lies within the Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests ecoregion, while the higher elevations along the eastern border and in the panhandle lie within the Appalachian-Blue Ridge forests. The native vegetation for most of the state was originally mixed hardwood forest of oak, chestnut, maple, beech, and white pine, with willow and American sycamore along the state's waterways. Many of the areas are rich in biodiversity and scenic beauty, a fact appreciated by native West Virginians, who refer to their home as Almost Heaven (from the song, "Take Me Home, Country Roads" by John Denver). Before the song, it was known as "The Cog State" (Coal, Oil, and Gas) or "The Mountain State".

The underlying rock strata are sandstone, shale, bituminous coal beds, and limestone laid down in a near-shore environment from sediments derived from mountains to the east, in a shallow inland sea on the west. Some beds illustrate a coastal swamp environment, some river delta, some shallow water. Sea level rose and fell many times during the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian eras, giving a variety of rock strata. The Appalachian Mountains are some of the oldest on earth, having formed more than three hundred million years ago.[59]

Climate

| West Virginia state-wide averages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

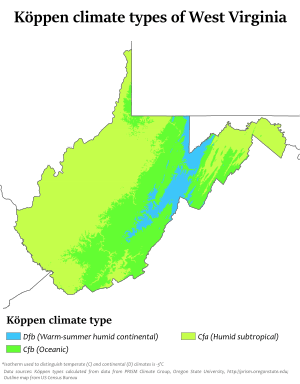

The climate of West Virginia is generally a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa, except Dfb at the higher elevations) with warm to hot, humid summers and chilly winters, increasing in severity with elevation. Some southern highland areas also have a mountain temperate climate (Köppen Cfb) where winter temperatures are more moderate and summer temperatures are somewhat cooler. However, the weather is subject in all parts of the state to change. The hardiness zones range from zone 5b in the central Appalachian mountains to zone 7a in the warmest parts of the lowest elevations.[60]

In the Eastern Panhandle and the Ohio River Valley, temperatures are warm enough to see and grow subtropical plants such as southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), crepe myrtle, Albizia julibrissin, American sweetgum and even the occasional needle palm and sabal minor. These plants do not thrive as well in other parts of the state. The eastern prickly pear grows well in many portions of the state.

Average January temperatures range from around 26 °F (−4 °C) near the Cheat River to 41 °F (5 °C) along sections of the border with Kentucky. July averages range from 67 °F (19 °C) along the North Branch Potomac River to 76 °F (24 °C) in the western part of the state. It is cooler in the mountains than in the lower sections of the state.[61] The highest recorded temperature in the state is 112 °F (44 °C) at Martinsburg on July 10, 1936 and the lowest recorded temperature in the state is −37 °F (−38 °C) at Lewisburg on December 30, 1917.

Annual precipitation ranges from less than 32 inches (810 mm) in the lower eastern section to more than 56 inches (1,400 mm) in higher parts of the Allegheny Front. Valleys in the east have lower rainfall because the Allegheny mountain ridges to the west create a partial rain shadow. Slightly more than half the rainfall occurs from April to September. Dense fogs are common in many valleys of the Kanawha section, especially the Tygart Valley. West Virginia is also one of the cloudiest states in the nation, with the cities of Elkins and Beckley ranking 9th and 10th in the U.S. respectively for the number of cloudy days per year (over 210). In addition to persistent cloudy skies caused by the damming of moisture by the Alleghenies, West Virginia also experiences some of the most frequent precipitation in the nation, with Snowshoe averaging nearly 200 days a year with either rain or snow. Snow usually lasts only a few days in the lower sections but may persist for weeks in the higher mountain areas. An average of 34 inches (860 mm) of snow falls annually in Charleston, although during the winter of 1995–1996 more than three times that amount fell as several cities in the state established new records for snowfall. Average snowfall in the Allegheny Highlands can range up to 180 inches (4,600 mm) per year. Severe weather is somewhat less prevalent in West Virginia than in most other eastern states, and it ranks among the least tornado-prone states east of the Rockies.

Adjacent states

- Pennsylvania (North)

- Maryland (Northeast)

- Kentucky (Southwest)

- Virginia (East)

- Ohio (West)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 55,873 | — | |

| 1800 | 78,592 | 40.7% | |

| 1810 | 105,469 | 34.2% | |

| 1820 | 136,808 | 29.7% | |

| 1830 | 176,924 | 29.3% | |

| 1840 | 224,537 | 26.9% | |

| 1850 | 302,313 | 34.6% | |

| 1860 | 376,688 | 24.6% | |

| 1870 | 442,014 | 17.3% | |

| 1880 | 618,457 | 39.9% | |

| 1890 | 762,794 | 23.3% | |

| 1900 | 958,800 | 25.7% | |

| 1910 | 1,221,119 | 27.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,463,701 | 19.9% | |

| 1930 | 1,729,205 | 18.1% | |

| 1940 | 1,901,974 | 10.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,005,552 | 5.4% | |

| 1960 | 1,860,421 | −7.2% | |

| 1970 | 1,744,237 | −6.2% | |

| 1980 | 1,949,644 | 11.8% | |

| 1990 | 1,793,477 | −8.0% | |

| 2000 | 1,808,344 | 0.8% | |

| 2010 | 1,852,994 | 2.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 1,792,147 | −3.3% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[62] 2019 Estimate[63] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of West Virginia was 1,792,147 on July 1, 2018, a 3.28% decrease since the 2010 United States Census.[63] The center of population of West Virginia is located in Braxton County, in the town of Gassaway.[64]

At the 2010 Census, the racial composition of the state's population was:

- 93.2% of the population was non-Hispanic White

- 3.4% non-Hispanic Black or African American

- 0.2% non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native

- 0.7% non-Hispanic Asian American

- 0.1% from some other race (non-Hispanic)

- 1.3% Multiracial American (non-Hispanic).

In the same year, 1.2% of West Virginia's population was of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (they may be of any race).

| Racial composition | 1990[65] | 2000[66] | 2010[67] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 96.2% | 95.0% | 93.9% |

| Black | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.4% |

| Asian | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.7% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | – |

| Other race | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Two or more races | – | 0.9% | 1.5% |

As of 2018, West Virginia has an estimated population of 1,805,832, which is a decrease of 10,025 (0.55%) from the prior year and a decrease of 47,162 (2.55%) since the previous census. This includes a natural decrease of 3,296 (108,292 births minus 111,588 deaths) and an increase from net migration of 14,209 into the state. West Virginia is the least populous southeastern state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 3,691, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 10,518.

Only 1.1% of the state's residents were foreign-born, placing West Virginia last among the 50 states in that statistic. It also has the lowest percentage of residents who speak a language other than English in the home (2.7%).

The five largest ancestry groups in West Virginia are: German (18.9%), Irish (15.1%) American (12.9%), English (11.8%) and Italian (4.7%)[68][69] In the 2000 Census People who identified their ethnicity as simply American made up 18.7% of the population.[70]

Large numbers of people of German ancestry are present in the northeastern counties of the state. People of English ancestry are present throughout the entire state. Many West Virginians who self-identify as Irish are actually Scots-Irish Protestants.

2010 census data show that 16 percent of West Virginia's residents are 65 or older (exceeded only by Florida's 17 percent).[71]

| State | % of population |

|---|---|

| Florida | 17.3 |

| West Virginia | 16.0 |

| Maine | 15.9 |

| Pennsylvania | 15.4 |

| Iowa | 14.9 |

| Montana | 14.8 |

| Vermont | 14.6 |

| North Dakota | 14.5 |

| Rhode Island | 14.4 |

| Arkansas | 14.4 |

There were 20,928 births in 2006. Of these, 19,757 (94.40% of the births, 95.19% of the population) were to non-Hispanic whites. There were 22 births to American Indians (0.11% of the births and 0.54% of the population), 177 births to Asians (0.85% of the births and 0.68% of the population), 219 births to Hispanics (1.05% of the births and 0.88% of the population) and 753 births to blacks and others (3.60% of the births and 3.56% of the population).[73]

The state's Northern Panhandle, and North-Central region feel an affinity for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Also, those in the Eastern Panhandle feel a connection with the Washington, D.C. suburbs in Maryland and Virginia, and southern West Virginians often consider themselves Southerners. Finally, the towns and farms along the mid-Ohio River, which forms most of the state's western border, have an appearance and culture somewhat resembling the Midwest.[74]

Birth data

Note: Births in table do not add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[76] | 2014[77] | 2015[78] | 2016[79] | 2017[80] | 2018[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| white: | 19,823 (95.2%) | 19,245 (94.8%) | 18,814 (95.0%) | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic white | 19,542 (93.8%) | 18,860 (92.9%) | 18,442 (93.1%) | 17,460 (91.5%) | 16,943 (90.7%) | 16,621 (91.1%) |

| Black | 754 (3.6%) | 813 (4.0%) | 738 (3.7%) | 587 (3.1%) | 629 (3.4%) | 626 (3.4%) |

| Asian | 229 (1.1%) | 214 (1.0%) | 225 (1.1%) | 170 (0.9%) | 201 (1.1%) | 176 (1.0%) |

| American Indian | 19 (0.1%) | 29 (0.1%) | 28 (0.1%) | 17 (0.1%) | 26 (0.1%) | 16 (0.1%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 219 (1.1%) | 350 (1.7%) | 331 (1.7%) | 378 (2.0%) | 390 (2.1%) | 378 (2.1%) |

| Total West Virginia | 20,825 (100%) | 20,301 (100%) | 19,805 (100%) | 19,079 (100%) | 18,675 (100%) | 18,248 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of white Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Religion

Several surveys have been made in recent years, in 2008 by the American Religion Identity Survey,[83] in 2010 by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.[84] The Pew survey results admit to a 6.5% margin of error plus or minus, while the ARIS survey says "estimates are subject to larger sampling errors in states with small populations." A characteristic of religion in Appalachian communities is the abundance of independent, non-affiliated churches, which "remain unnoted and uncounted in any census of church life in the United States". This sometimes leads to the belief that these communities are "unchurched".[85]

The largest denomination as of 2010 was the United Methodist Church with 136,000 members in 1,200 congregations. The second-largest Protestant church was the American Baptist Churches USA with 88,000 members and 381 congregations. The Southern Baptist church had 44,000 members and 232 congregations. The Churches of Christ had 22,000 members and 287 congregations. The Presbyterian Church (USA) had 200 congregations and 20,000 members.[86]

A survey conducted in 2015 by the Pew Research Center found that West Virginia was the seventh most "highly religious" state in the United States.[87]

Economy

Overview

The economy of West Virginia nominally would be the 62nd largest economy globally behind Iraq and ahead of Croatia according to 2009 World Bank projections,[88] and the 64th largest behind Iraq and ahead of Libya according to 2009 International Monetary Fund projections.[89] The state has a projected nominal GSP of $63.34 billion in 2009 according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis report of November 2010, and a real GSP of $55.04 billion. The real GDP growth of the state in 2009 of .7% was the 7th best in the country.[90] West Virginia was one of only ten states in 2009 that grew economically.[91]

While per capita income fell 2.6% nationally in 2009, West Virginia's grew at 1.8%.[92] Through the first half of 2010, exports from West Virginia topped $3 billion, growing 39.5% over the same period from the previous year and ahead of the national average by 15.7%.[92]

Morgantown was ranked by Forbes as the #10 best small city in the nation to conduct business in 2010.[93] The city is also home to West Virginia University, the 95th best public university according to U.S. News & World Report in 2011.[94] The proportion of West Virginia's adult population with a bachelor's degree is the lowest in the U.S. at 17.3%.[95]

The net corporate income tax rate is 6.5% while business costs are 13% below the national average.[96][97]

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that in 2014 West Virginia's economy grew twice as fast as the next fastest growing state East of the Mississippi River, ranking third alongside Wyoming and just behind North Dakota and Texas among the fastest growing states in the United States.[98]

Tourism

Tourism contributed $4.27 billion to the state's economy and employed 44,400 people in 2010, making it one of the state's largest industries.[99] Many tourists, especially in the eastern mountains, are drawn to the region's notable opportunities for outdoor recreation. Canaan Valley is popular for winter sports, Seneca Rocks is one of the premier rock climbing destinations in the eastern U.S., the New River Gorge/Fayetteville area draws rock climbers as well as whitewater rafting enthusiasts, and the Monongahela National Forest is popular with hikers, backpackers, hunters, and anglers.

In addition to such outdoor recreation opportunities, the state offers a number of historic and cultural attractions. Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is a historic town situated at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. Harpers Ferry was the site of John Brown's 1859 raid on the U.S. Armory and Arsenal. Located at the approximate midpoint of the Appalachian Trail, Harpers Ferry is the base of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

The Greenbrier hotel and resort, originally built in 1778, has long been considered a premier hotel, frequented by numerous world leaders and U.S. presidents over the years.

West Virginia is the site of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which features the Green Bank Telescope. For the 1963 Centennial of the State, it hosted two high school graduate delegates from each of the 50 States at the National Youth Science Camp near Bartow, and has continued this tradition ever since. The main building of Weston State Hospital is the largest hand-cut sandstone building in the western hemisphere, second worldwide only to the Kremlin in Moscow. Tours of the building, which is a National Historic Landmark and part of the National Civil War Trail, are offered seasonally and by appointment year round. West Virginia has numerous popular festivals throughout the year.

Resources

One of the major resources in West Virginia's economy is coal. According to the Energy Information Administration, West Virginia is a top coal-producer in the United States, second only to Wyoming. West Virginia is located in the heart of the Marcellus Shale Natural Gas Bed, which stretches from Tennessee north to New York in the middle of Appalachia.

As of 2017, the coal industry accounted for 2% of state employment.[100]

Nearly all the electricity generated in West Virginia is from coal-fired power plants. West Virginia produces a surplus of electricity and leads the Nation in net interstate electricity exports.[101] Farming is also practiced in West Virginia, but on a limited basis because of the mountainous terrain over much of the state.

Green energy

West Virginia has the potential to generate 4,952 GWh/year from 1,883 MW of wind power, using 80 meter high wind turbines, or 8,627 GWh/year from 2,772 MW of 100 meter wind turbines, and 60,000 GWh from 40,000 MW of photovoltaics, including 3,810 MW of rooftop photovoltaics.[102]

| West Virginia Wind Generation (GWh, Million kWh) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Capacity (MW) |

Total | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| 2009 | 330 | 742 | 86 | 86 | 69 | 71 | 31 | 49 | 49 | 32 | 46 | 71 | 68 | 86 |

| 2010 | 431 | 939 | 92 | 79 | 85 | 86 | 66 | 69 | 49 | 33 | 66 | 114 | 89 | 112 |

| 2011 | 564 | 1099 | 102 | 113 | 112 | 114 | 49 | 62 | 45 | 68 | 60 | 122 | 124 | 132 |

| 2012 | 583 | 1286 | 201 | 147 | 136 | 130 | 59 | 90 | 85 | 41 | 65 | 98 | 100 | 133 |

| 2013 | 583 | 1387 | 175 | 154 | 174 | 140 | 134 | 78 | 55 | 58 | 52 | 58 | 159 | 152[103] |

| 2014 | 583 | 1451 | 166 | 146 | 167 | 143 | 100 | 62 | 76 | 64 | 67 | 154 | 157 | 149 |

| 2015 | 583 | 1376 | 158 | 137 | 181 | 137 | 75 | 103 | 65 | 44 | 71 | 122 | 147 | 136 |

| 2016 | 686 | 1432 | 166 | 164 | 134 | 120 | 74 | 92 | 69 | 57 | 67 | 130 | 135 | 222 |

| 2017 | 686 | 1682 | 124 | 123 | 171 | 174 | 152 | 140 | 112 | 52 | 70 | 116 | 167 | 211 |

| 2018 | 686 | 1779 | 191 | 181 | 183 | 180 | 138 | 132 | 97 | 108 | 106 | 144 | 160 | 160 |

| 2019 | 160 | 131 | 144 | 185 | 152 | 162 | ||||||||

Taxes

West Virginia personal income tax is based on federal adjusted gross income (not taxable income), as modified by specific items in West Virginia law. Citizens are taxed within five income brackets, which range from 3.0% to 6.5%. The state's consumer sales tax is levied at 6% on most products except for non-prepared foods.[108]

West Virginia counties administer and collect property taxes, although property tax rates reflect levies for state government, county governments, county boards of education and municipalities. Counties may also impose a hotel occupancy tax on lodging places not located within the city limits of any municipality that levies such a tax. Municipalities may levy license and gross receipts taxes on businesses located within the city limits and a hotel occupancy tax on lodging places in the city. Although the Department of Tax and Revenue plays a major role in the administration of this tax, less than half of one percent of the property tax collected goes to state government.

The primary beneficiaries of the property tax are county boards of education. Property taxes are paid to the sheriff of each of the state's 55 counties. Each county and municipality can impose its own rates of property taxation within the limits set by the West Virginia Constitution. The West Virginia legislature sets the rate of tax of county boards of education. This rate is used by all county boards of education statewide. However, the total tax rate for county boards of education may differ from county to county because of excess levies. The Department of Tax and Revenue supervises and otherwise assists counties and municipalities in their work of assessment and tax rate determination. The total tax rate is a combination of the tax levies from four state taxing authorities: state, county, schools and municipal. This total tax rate varies for each of the four classes of property, which consists of personal, real and intangible properties. Property is assessed according to its use, location and value as of July 1. WV Assessments has a free searchable database of West Virginia real estate tax assessments, covering current and past years. All property is reappraised every three years; annual adjustments are made to assessments for property with a change of value. West Virginia does not impose an inheritance tax. Because of the phase-out of the federal estate tax credit, West Virginia's estate tax is not imposed on estates of persons who died on or after January 1, 2005.[109]

Largest private employers

The largest private employers in West Virginia, as of March 2019, were: [110]

| Rank | Company |

|---|---|

| 1 | WVU Medicine |

| 2 | Walmart |

| 3 | CAMC Health System |

| 4 | Mountain Health Network |

| 5 | Kroger |

| 6 | Lowe's Home Centers |

| 7 | Contura Energy |

| 8 | Wheeling Hospital, Inc. |

| 9 | Mylan Pharmaceuticals |

| 10 | Murray American Energy |

| 11 | ResCare |

| 12 | Mon Health |

| 13 | Macy's Corporate Services |

| 14 | American Electric Power |

| 15 | West Virginia's Choice, Inc. |

| 16 | FirstEnergy Corp |

| 17 | Dolgencorp, LLC (Dollar General Stores) |

| 18 | Thomas Health Systems |

| 19 | Pilgrim's Pride Corporation of West Virginia |

| 20 | Frontier West Virginia |

| 21 | Blackhawk Mining, LLC |

| 22 | General Mills Restaurants, Inc. |

| 23 | Arch Coal, Inc. |

| 24 | Walgreens |

| 25 | DowDuPont, Inc. |

Quality of life

Economy

West Virginia governor Tomblin's proposed 2014–15 budget submitted in January 2014 had an estimated budget gap of $146–$265 million, and halfway through the 2013–14 fiscal year, tax revenues were $82 million short.[111] The West Virginia Legislature in March 2014 passed its budget bill, taking $147 million from the Rainy Day Fund to balance the 2015 budget.[112] Governor Tomblin's deputy chief of staff Jason Pizatella, after the state legislature passed the budget, said West Virginia is expecting another dismal budget in 2016 and could need $150–170 million to balance the next year's budget.[113]

West Virginia coal exports declined 40% in 2013—a loss of $2.9 billion and overall total exports declined 26%.[114] West Virginia ranked last in the Gallup Economic Index for the fourth year running. West Virginia's score was −44, or a full 17 points lower than the average of −27 for the other states in the bottom ten.[115] West Virginia ranked 48th in the CNBC "Top States for Business 2013" based on measures of competitiveness such as economy, workforce and cost of living—ranking among the bottom five states for the last six years running.[116] West Virginia ranked 49th in the 2014 State New Economy Index, and has ranked in the bottom three states since 1999. West Virginia ranked last or next-to-last in critical indicators such as Workforce Education, Entrepreneurial Activity, High-Tech Jobs, and Scientists and Engineers.[117]

On January 9, 2014, a chemical spill contaminated the water supply of 300,000 people in nine West Virginia counties near Charleston. According to Bloomberg News, lost wages, revenue, and other economic harm from the chemical spill could top $500 million.[118] and West Virginia's Marshall University Center for Business and Economic Research estimated that about $61 million was lost by businesses in the first four days alone after the spill.[119]

Employment

In 2012, West Virginia's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 3.3%.[120] The state issued a report highlighting the state's GDP as indicating a fast-growing economy, but did not address employment indicators.[121] In 2009–2013, the U.S. real GDP increased 9.6% and total employment increased 3.9%. In West Virginia during the same time period, its real GDP increased about 11%, while total employment decreased by 1,000 jobs from 746,000 to 745,000.

In 2013, West Virginia ranked last in the nation with an employment-to-population ratio of only 50%, compared to the national average of 59%.[122] The state lost 5,600 jobs in its labor force in four critical economic sectors: construction (1,900), manufacturing (1,100), retail (1,800), and education (800), while gaining just 400 in mining and logging.[123] The state's Civilian Labor Force dropped by 15,100.[124]

Wages and poverty

Personal income growth in West Virginia during 2013 was only 1.5%—the lowest in the nation—and about half the national average (2.6%).[125] Overall income growth in West Virginia in the last thirty years has been only 13%—about a third the national average (37%). Wages of the impoverished bottom 1% income earners decreased by 3%, compared to the national average, which increased 19%.[126]

West Virginia's poverty rate is one of the highest in the nation. 2017 estimates indicate that 19% of the state's population lives in poverty, exceeding the national average of 13%.[127]

The West Virginia teachers' strike in 2018 inspired teachers in other states to take similar action.[128]

Population

United Van Lines 37th Annual Migration Study showed in 2013 that 60% more people moved out of the Mountain State than moved in.[129] West Virginia's population is expected to decline by more than 19,000 residents by 2030, and West Virginia could lose one of its three seats in the United States House of Representatives.[130] West Virginia is the only state where death rates exceeds birth rates. During 2010–2013, about 21,000 babies per year were born in West Virginia, but over these three years West Virginia had 3,000 more deaths than births.[131]

Family

Gallup-Healthways annual "State of American Well-Being" rankings reports that 1,261 concerned West Virginians rated themselves as "suffering" in categories such as Quality of Life, Physical Health, and Access to Basic Needs. Overall, West Virginia citizens rated themselves as being more miserable than people in all other states—for five years running.[132] In addition, the Gallup Well-Being Index for 2013 ranked Charleston, the state capital, and Huntington last and next-to-last out of 189 U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Areas.[133]

The Annie E. Casey Foundation's National Index of Children's Progress ranked West Virginia 43rd in the nation for all kids, and last for white kids.[134] The Annie E. Casey Foundation's 2013 KIDS COUNT Data Book also ranked West Virginia's education system 47th in the nation for the second straight year.[135] Charleston, West Virginia has the worst divorce rate among 100 cities in the nation. Stephen Smith, the executive director of the West Virginia Healthy Kids and Families Coalition, said poor employment prospects are to blame: "The pressure to make a good living puts strain on a marriage, and right now it is infinitely harder to make a living here than it was 40 years ago."[136]

Health

United Health Foundation's "America's Health Rankings" for 2013 found that Americans are making considerable progress in key health measures. West Virginia, however, ranked either last or second-to-last in twenty categories, including cancer, child immunization, diabetes, disabilities, drug deaths, teeth loss, low birth weight, missed work days due to health, prescription drug overdose, preventable hospitalizations, and senior clinical care.[137] Wisconsin Population Health Institute annual "Health Rankings" for 2012 showed West Virginia spends $9,671 per capita on health care annually. El Salvador spends just $467, yet both have the same life expectancy.[138] In 2012, according to the Census Bureau, West Virginia was the only state where death rates exceeds birth rates. During 2010–2013, about 21,000 babies per year were born in West Virginia, but there were 24,000 deaths.[131] In demographics, this is called a "net mortality society".[139]

The National Center for Health Statistics says national birth rates for teenagers are at historic lows—during 2007–2010, teen birth rates fell 17% nationally;. West Virginia, however, ranked last with a 3% increase in birth rates for teenagers.[140] A study by West Virginia's Marshall University showed that 19% of babies born in the state have evidence of drug or alcohol exposure.[141] This is several times the national rate, where studies show that about 5.9% of pregnant women in the U.S. use illicit drugs, and about 8.5% consume any alcohol.[142] An Institute for Health Policy Research study determined that mortality rates in Appalachia are correlated with coal production. In twenty West Virginia coal counties mining more than a million tons of coal per year and having a total population of 850,000, there are about 10,100 deaths per year, with 1,400 of those statistically attributed to deaths from heart, respiratory and kidney disease from living in an Appalachian coal county.[143]

In 2015, McDowell County had the highest rate of drug-induced deaths of any county in the United States, with a rate of 141 deaths per 100,000 people. Four of the five counties with the highest rates of drug-induced deaths are in West Virginia (McDowell, Wyoming, Cabell and Raleigh Counties).[144]

Governance

in Charleston

Legislative branch

The West Virginia Legislature is bicameral. It consists of the House of Delegates and the Senate, both housed in the West Virginia State Capitol. It is a citizen's legislature, meaning that legislative office is not a full-time occupation, but rather a part-time position. Consequently, the legislators often hold a full-time job in their community of residence.

Typically, the legislature is in session for 60 days between January and early April. The final day of the regular session ends in a bewildering fury of last-minute legislation to meet a constitutionally imposed midnight deadline. During the remainder of the year, monthly interim sessions are held in preparation for the regular session. Legislators also gather periodically for 'special' sessions when called by the governor.

The title of Lieutenant Governor is assigned by statute to the senate president.

Executive branch

The governor, elected every four years on the same day as the U.S. presidential election, is sworn in during the following January.

Governors of West Virginia can serve two consecutive terms but must sit out a term before serving a third term in office.

The title of Lieutenant Governor is assigned by statute to the senate president.

Judicial branch

West Virginia is one of nineteen states that do not have a death penalty, and it is the only state in the southeastern United States to have abolished it.

For the purpose of courts of general jurisdiction, the state is divided into 31 judicial circuits. Each circuit is made up of one or more counties. Circuit judges are elected in non-partisan elections to serve eight-year terms.

West Virginia's highest court is the Supreme Court of Appeals. The Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia is the busiest appellate court of its type in the United States. West Virginia is one of 11 states with a single appellate court. The state constitution allows for the creation of an intermediate court of appeals, but the Legislature has never created one. The Supreme Court is made up of five justices, elected in non-partisan elections to 12-year terms.

West Virginia is an alcoholic beverage control state. However, unlike most such states, it does not operate retail outlets, having exited that business in 1990. It retains a monopoly on wholesaling of distilled spirits only.

Politics

.jpg)

At the state level, West Virginia's politics were largely dominated by the Democratic Party from the Great Depression through the 2000s. This was a legacy of West Virginia's very strong tradition of union membership.[145] After the 2014 midterm elections Democrats controlled the governorship, the majority of statewide offices, and one U.S. Senate seat, while Republicans held one U.S. Senate seat, all three of the state's U.S. House seats, and a majority in both houses of the West Virginia Legislature. In the 2016 elections, the Republicans held on to their seats and made gains in the State Senate and gained three statewide offices.[146][147]

Since 2000, West Virginians have supported the Republican candidate in every presidential election. The state is regarded as a "deep red" state at the federal level.[145][148] In 2012 Republican Mitt Romney won the state, defeating Democrat Barack Obama with 62% of the vote to 35% for Obama. In the 2016 presidential election, Republican Donald Trump won the state with 67.86% of the popular vote, with West Virginia being the second-highest percentage voting for Trump of any state.[149]

Evangelical Christians comprised 52% of the state's voters in 2008.[150] A poll in 2005 showed that 53% of West Virginia voters are anti-abortion, the seventh highest in the country.[151] A 2014 poll by Pew Research found that 35% of West Virginians supported legal abortion in "all or most cases" while 58% wanted it to be banned "in all or most cases".[152] A September 2011 Public Policy Polling survey found that 19% of West Virginia voters thought same-sex marriage should be legal, while 71% thought it should be illegal and 10% were not sure. A separate question on the same survey found that 43% of West Virginia voters supported the legal recognition of same-sex couples, with 17% supporting same-sex marriage, 26% supporting civil unions but not marriage, 54% favoring no legal recognition and 3% not sure.[153] In 2008, 58% favored troop withdrawal from Iraq while just 32% wanted troops to remain.[154] On fiscal policy in 2008, 52% said raising taxes on the wealthier individuals would benefit the economy, while 45% disagreed.[155]

West Virginia Department of Commerce

The West Virginia Department of Commerce is a government agency responsible for overseeing West Virginia's economy, workforce, natural resources, and tourism, the department oversees nine subsidiary agencies.[156]

Subsidiary agencies

- West Virginia Development Office

- West Virginia Division of Forestry

- West Virginia Division of Labor

- West Virginia Division of Natural Resources

- West Virginia Division of Tourism

- West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey

- West Virginia Office of Miners' Health, Safety and Training

- WORKFORCE West Virginia

- West Virginia Division of Energy

Transportation

Highways form the backbone of transportation systems in West Virginia, with over 37,300 miles (60,000 km) of public roads in the state.[157] Airports, railroads, and rivers complete the commercial transportation modes for West Virginia. Commercial air travel is facilitated by airports in Charleston, Huntington, Morgantown, Beckley, Lewisburg, Clarksburg, and Parkersburg. All but Charleston and Huntington are subsidized by the federal Department of Transportation's Essential Air Service program. The cities of Charleston, Huntington, Beckley, Wheeling, Morgantown, Clarksburg, Parkersburg and Fairmont have bus-based public transit systems.

West Virginia University in Morgantown boasts the PRT (personal rapid transit) system, the state's only single-rail public transit system. Developed by Boeing, the WVU School of Engineering and the Department of Transportation, it was a model for low-capacity light transport designed for smaller cities. Recreational transportation opportunities abound in West Virginia, including hiking trails,[158] rail trails,[159] ATV off-road trails,[160] white water rafting rivers,[161] and two tourist railroads, the Cass Scenic Railroad[162] and the Potomac Eagle Scenic Railroad.[163]

West Virginia is crossed by seven Interstate Highways. I-64 enters the state near White Sulphur Springs in the mountainous east, and exits for Kentucky in the west, near Huntington. I-77 enters from Virginia in the south, near Bluefield. It runs north past Parkersburg before it crosses into Ohio. I-64 and I-77 between Charleston and Beckley are merged as toll road known as the West Virginia Turnpike, which continues as I-77 alone from Beckley to Princeton. It was constructed beginning in 1952 as a two lane road, but rebuilt beginning in 1974 to Interstate standards. Today almost nothing of the original construction remains. I-68's western terminus is in Morgantown. From there it runs east into Maryland. At the I-68 terminus in Morgantown, it meets I-79, which enters from Pennsylvania and runs through the state to its southern terminus in Charleston. I-70 briefly runs through West Virginia, crossing the northern panhandle through Wheeling, while I-470 is a bypass of Wheeling (making Wheeling among the smallest cities with an interstate bypass). I-81 also briefly runs in West Virginia through the Eastern Panhandle where it goes through Martinsburg.

The interstates are supplemented by roads constructed under the Appalachian Corridor system. Four Corridors are complete. Corridor D, carrying US 50, runs from the Ohio River, and I-77, at Parkersburg to I-79 at Clarksburg. Corridor G, carrying US 119, runs from Charleston to the Kentucky border at Williamson. Corridor L, carrying US 19, runs from the Turnpike at Beckley to I-79 near Sutton (and provides a short cut of about 40 miles (64 km) and bypasses Charleston's urban traffic for traveler heading to and from Florida). Corridor Q, carrying US 460, runs through Mercer County, entering the state from Giles County, Virginia and then reentering Virginia at Tazewell County.