Keyser, West Virginia

Keyser (/ˈkaɪ.zər/) is a city in and the county seat of Mineral County,[6] West Virginia, United States. It is part of the Cumberland, MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 5,439 at the 2010 census.

Keyser, West Virginia The Irish Settlement (c.1752)

Paddy Town (c.1752-1855) Wind Lea (1855-c.1860) New Creek (c.1860-1874) | |

|---|---|

Downtown Keyser in January 2014 | |

Location of Keyser in Mineral County, West Virginia. | |

| Coordinates: 39°26′20″N 78°58′58″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Mineral |

| Incorporated/Chartered | 1874/1913 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.98 sq mi (5.12 km2) |

| • Land | 1.98 sq mi (5.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 807 ft (246 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 5,439 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 4,915 |

| • Density | 2,488.61/sq mi (960.77/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 26726 |

| Area code(s) | 304 |

| FIPS code | 54-43492[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1541180[5] |

| Website | Official website |

History

Keyser, the county seat of Mineral County, is located on the North Branch of the Potomac River at its juncture with New Creek in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. Throughout the centuries, the town went through a series of name changes, but was ultimately named after William Keyser, a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad official.[7]

The Early Days: Paddy Town

The first Europeans to pass through what would become present-day Keyser are believed to have been William Mayo and George Savage, sent by Lord Fairfax in 1736 to seek out the source of the Potomac River. The first local land grant was issued by Fairfax to Christopher Beelor on March 20, 1752.

The place was first called Paddy Town, for Patrick McCarty, an Irish immigrant who came to then-Hampshire County, Virginia, sometime after 1740. Eventually, a community developed, which was also known as "the Irish Settlement." Initially a peaceful village, Paddy Town came under repeated Indian attacks after Major General Edward Braddock's defeat west of Paddy Town by French and Indian forces in 1755. The Paddy Towners built stockades and blockhouses to protect themselves. In 1762, Patrick McCarty was killed by a band of Indians while harvesting crops.[8]

Patrick McCarty's son, Edward McCarty, was an enterprising fellow who put Paddy Town on the map after his father's death. Among other things, he built an iron furnace and foundry and a salt well, near present-day Armstrong Street. According to an 1851 newspaper article, during the Revolutionary War, "there were extensive borings for salt at Paddytown, on the Virginia side of the Potomac, and that after reaching a depth of 600 feet, the supply of salt water was abundant, from which large quantities of this article was manufactured."[9]

The Paddy Town, Virginia, post office was established on October 30, 1811.[10] The McCarty family built a stone house in 1815, still standing today at Keys Street in Keyser.[11] A travel guide described the town in these formative years:

Paddytown, Va. post office vacant 1835. Is a small, romantic village, 214 miles from Richmond and 135 miles Northwest from Washington. Has 6 dwelling houses, 1 mercantile store, 1 manufacturing flour mill, and in immediate vicinity 1 forge and iron furnace. Romantic scenery, especially Slim Bottom Hill (Queen's Point). Lands in immediate vicinity belong to James Singleton.[12]

As the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O Canal) was constructed alongside the Potomac, from Washington, DC, to Cumberland, Maryland, a resident of the Potomac valley wrote to the editors of the National Intelligencer in Washington in 1837, seeking to make a sale:

At a place called Paddy Town, the residence of the late Col. Edward McCarty, on the North branch, 25 miles above Cumberland, stands an excellent furnace and forge, for making iron, now idle for want of capital and skill to work them. These may be said to stand in the great coal region of the Potomack, or so near that the coal can be delivered at them for 3 cents per bushel. Col. McCarty, who built them, and who was a man of great enterprise, failed by attempting too much at once without sufficient skill.[13]

The C&O Canal was originally planned to reach the Ohio River, but it never made it as far as Paddy Town, let alone the Ohio, overtaken by a railroad and stopping as far west as Cumberland.

Paddy Town fell into decline by 1844, when the original post office closed. Then, in 1852, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, in search of a path through the Alleghenies, arrived, giving the town an economic boost.[14] The Paddy Town post office was re-established that year, with Edward Hitchcock McDonald as postmaster. McDonald's wife Cornelia Peak McDonald was an educated socialite from the city of Alexandria, Virginia, and thought the name "Paddy Town" was "unaesthetic and wholly unacceptable." Through her persistent lobbying, the Post Office Department renamed the town's post office Wind Lea, Virginia, in 1855.[15]

Mrs. McDonald's literary flourish for the post office did not stick to the town. Sometime between 1855 and the start of the Civil War, the townsfolk renamed the village New Creek Station, after the creek that runs by it. This decision was supposedly "by common consent" to give the town a "more dignified" name.[16]

The Civil War: New Creek

In 1861, the American Civil War came to New Creek Station in then-Hampshire County, Virginia. The Union established Fort Fuller on the present site of Potomac State College of West Virginia University. The fort's commanders included Majors Lew Wallace and Benjamin Harrison, the author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ and the 23rd President of the United States, respectively.[17] The area changed hands 14 times during the war due to the importance of the railroad.[18] One history describes "four years of carnage" at New Creek ... everything was laid to waste. What buildings of importance had been built, many of which were equal to those of other towns in that day, were razed to the ground or reduced to ashes, by the relentless flames of the military incendiary."[19] The railroad that had been a blessing to the town had turned into a curse, drawing repeated assaults by Confederate forces.

A Harrisonburg, Virginia, newspaper provided a report of the exploits at New Creek of a Confederate company known as the Brook's Gap Rifles, which had been stationed at Romney in the summer of 1861:

A part of the company -- 18 members, a detachment under command of Lieut. Philip Kennon -- participated in the fight at New Creek Station, heretofore known as Paddytown, on the Balt. & O. Railroad, in Hampshire county. In this skirmish these sharp-shooters did first-rate work, private Black himself killing three of the enemy with his rifle, and private John W. West giving another a load of buckshot in the face. Black, who is a splendid equestrian as well as a "deadshot," charged up on the platform at the Station, riding on 7 or 8 feet. The enemy then drived into a house in which our boys peppered them, killing 5 or 6 with their deadly Minnie Rifles, which they handle with terrible precision.[20]

Because of its geography, a relatively flat plain in a valley surrounded by mountains and open to many approaches, New Creek was an easy target for Confederates. One editor in Wheeling, West Virginia, opined that holding New Creek was useless, writing in 1863:

The concentration of troops at New Creek and the preparations there for attack or siege, indicate that it is the intention of our military authorities to hold that post against rebel investment ... New Creek ... really protects nothing but the little valley which its guns command. It cannot prevent the progress of the rebels into Pennsylvania or into Western Virginia. ... We do not undertake to say what points could be made to protect West irginia or Western Pennsylvania. We only express the opinion, in which we are not alone, that New Creek is not one of them ... It is to be hoped the folly of Winchester is not to be repeated at New Creek -- of holding a useless and indefensible position, which if not in the enemy's country now could easily be made so by their getting in its rear.[21]

Again and again, the Confederates raided New Creek. The little town was under constant siege. In January 1864, according to one report, a rebel force of 3,000 cavalry was headed in the direction of New Creek, and New Creek residents "were forbidden to exhibit lights" after dark.[22]

Complete disaster finally visited New Creek on November 28, 1864. At 1 p.m. on a Monday afternoon, between 1,500 and 2,000 Confederates attacked a small garrison of Union troops stationed behind earthworks at Fort Fuller. The Union troops were quickly overcome. The Confederates then took over the town, destroying the earthworks and nearly all the buildings, except the home of Colonel Edward Armstrong, whom they knew to be a Confederate officer. A smaller Confederate force was then sent to Piedmont, where they managed to burn the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's roundhouse, a workshop, and other machinery before they were turned away by Company A Sixth West Virginia Volunteers.[23]

The residents of New Creek were terrorized by the November 1864 occupation. Men were captured and taken away. One eyewitness complained of the rebels' behavior:

... the chief thief among the rebels was a drunken, blear-eyed, pug nosed Major Mason, son of Ex-Senator James M. Mason. This fellow searched and robbed with his own hands eighteen or twenty citizen prisoners, taking everything of value found upon their persons. Although thrice ordered by General Rosser to send his prisoners to the front, he refused to obey until he had finished his pocket picking. After leaving New Creek, the rebels put the prisoners on the double-quick and ran them through the mud for about three miles. When any of the prisoners would attempt to avoid a miry place in the road, which they frequently did, they were rewarded for their care by a slap across the head or shoulders with a sabre. A great many prisoners made their escape along the route. The [rebels] nearly all got stone blind drunk, and they had about as much as they could do to look after the mule's load of booty which each of them carried. They ha also lost a great deal of rest previous to the attack on New Creek, and for these reasons the men were not very watchful. That old hero, Abijah Dolly, formerly a member of the Legislature, was one of the prisoners taken from New Creek. He made his escape, ran on ahead of the rebels, reached his farm, and drove off and concealed all his stock before the rebel advance came up.[24]

_Cavalry%2C_Union_Army%2C_New_Creek_(Keyser)%2C_W.Va.jpg)

During the war, in 1863, with the formation of West Virginia, the town found itself in a new state. Likely because this northern half of Hampshire County had stronger pro-Union sentiments and Romney was often occupied by Confederates, the new West Virginia legislature moved the county seat from Romney to Piedmont, a few miles up the Potomac from New Creek, until the war ended.[25] Following the war, the state legislature sent the Hampshire County seat back to Romney and split this northern half away to form Mineral County in 1866. Debate ensued over whether Piedmont or New Creek should be the county seat.

At this time, a New Creek citizen named Colonel Edward McCarty Armstrong returned from the war, having fought for the Confederacy, and sold his holdings in and around the town to three Davis brothers from Piedmont: Henry Gassaway Davis, William Davis, and Colonel Thomas B. Davis. The Davis brothers set about making the most of their real estate investment, knowing its value would increase if New Creek became the county seat and a greater hub of activity. They donated a major plot of land to the county court for the construction of a courthouse. The court enthusiastically accepted, and New Creek became Mineral's county seat.[26] Until then, the court met in an abandoned Union army hospital on the river bank. The stone courthouse was completed in 1868, was remodeled in 1896, and stands in use to this day.[27]

Incorporation of Keyser

The courthouse question was not the only field of competition between Piedmont and New Creek, as the towns sought to develop in these post-war years. In 1874, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was looking for a place to set up division headquarters. Once again, the town of New Creek won out in the marketing war. The town's trump card was its willingness to change its name, having already gone from Paddy Town to Wind Lea to New Creek. Thus, on November 16, 1874, the town of Keyser was incorporated. William Keyser was then the first vice president of the railroad, living in nearby Garrett County, Maryland, and in charge of the headquarters location division. The honor was too much to resist. In addition to the headquarters, the renamed town of Keyser received repair shops and a roundhouse, lifting employment and economic activity.[28] The town grew. New Creek would henceforth refer to an unincorporated community along the eponymous body of water just south of Keyser. The southern part of Keyser was known as South Keyser, a town unto itself. It would be combined with Keyser proper in 1913, when the state granted a charter to the City of Keyser.

The first mayor of Keyser was J.T. Hoke, elected unopposed with 127 votes on January 7, 1875.[29]

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Keyser played an early and prominent role in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. That year, in the midst of a deep nationwide depression ("the Long Depression") that had caused extensive unemployment and hunger, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad cut its employees' wages by 10 percent. On July 16, trainmen in Martinsburg, West Virginia, were the first to take action, uncoupling a cattle train and announcing no more trains would run through until the wage cuts were restored.[30] West Virginia Governor Henry M. Mathews sent militia under Colonel Charles J. Faulkner to restore order, but was unsuccessful largely due to militia sympathies with the workers.[31][32] The strike spread up and down the line and eventually across the entire country. Within two days, workers in Keyser—notably both black and white—voted to strike together, announcing:

Resolved, that we, the men of the Third Division, have soberly and calmly considered the step we have taken, and declare that at the present state of wages which the company have imposed upon us, we cannot live and provide our wives and children with the necessities of life, and that we only ask for wages that will enable us to provide such necessaries.[33]

The Boston Globe reported on July 18: "At Keyser a strike occurred this afternoon. The strikers threatened to shoot new men that take places on the road. No freight trains were sent from there."[34] On July 20, a train from Cumberland, Maryland, arrived in Keyser and was sent onto a side track, and strikers removed the crew with force.[35] That same day, federal troops arrived in Keyser to try to break the strike. The Philadelphia Times reported of events in Keyser: "The second troop train has just arrived here. A few men are around the station, but all is quiet. The men are firm in their determination not to run out any trains, but they will hardly attempt to stop others, as there is abundant military force."[36] However, by July 30, some 25 freight trains had piled up in Keyser.[37] That night a "misplaced switch" sent one of the trains off the tracks. The next day, under heavy military escort courtesy of U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, trains began moving out of Keyser.[38] The Baltimore Sun reported:

The troops at Keyser and Piedmont were deployed along the line of railroad property, keeping the crowds back at a considerable distance. No one [not] identified in the immediate employment of the company could pass the guard, and even the most irrepressible reporters found it necessary to make the most lengthy explanation of their privileges in order to pass the line. The strikers being kept back by the military, there was not the slightest interference with any of the trains ... The movement of the trains over this division has caused quite a general break among the strikers, and they are now constantly coming and asking to be set to work.[39]

Replacement workers were found, lured by Baltimore & Ohio vice president William Keyser's offer of fifty dollars for each strikebreaker. Meanwhile, any striker who approached the trains, now protected with military force, was immediately arrested. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad refused to rehire any of the leaders. And a manhunt was on in Keyser:

The authorities are endeavoring to detect the parties who threw the train off the track last night but have no clue as yet. Sheriff Simms has offered a reward of fifty dollars for the arrest of Joseph Lane, who escaped this morning. Lane was a ringleader of the striking firemen. The crowd that was arrested for attempting to ride free to Piedmont from here had a hearing before Mayor Shay this afternoon. Sixteen of them were discharged. Z. Knight, James Dixon, John Ravenscraft, and John Ashey were fined from three to ten dollars each and costs for carrying pistols, knives, and billies. Several of the parties were from the mining regions. Thomas Goff, as striking fireman, who led the crowd was fined ten dollars and costs and confined thirty days in jail, that being the extent of municipal authority. The others were sent to jail til they pay the fines.[39]

After three days of intense fighting along the line, the strike was broken in Keyser, with traffic moving again on August 1, 1877.[40] Company man William Keyser, after whom the town had just three years earlier named itself, held the line against the workers' demands. The wage cuts stood, but the strike spurred the burgeoning U.S. labor movement to begin organizing for both economic and political power, having seen the results when the state is in company hands—with the full force of courts, military deployments, arrests and imprisonment employed against the strikers—all of which were on full display in Keyser.

Across the Potomac from Keyser, in Westernport, Maryland, in the heat of the uprising, workers posted the following handbill, illustrating the desperation and militancy of the strike in this area:

WE SHALL CONQUER OR WE SHALL DIE Strike and Live! Bread we must have! Remain and perish! Be it understood, if the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company does not meet the demands of the employees at an early date, the officials will hazard their lives and endanger their property, for we shall run their trains and locomotives into the river; we shall blow up their bridges; we shall tear up their railroads; we shall consume their shops with fire and ravage their hotels with desperation. A company that has from time to time so unmercifully cut our wages and finally has reduced us to starvation, for such we have, has lost all sympathy. We have humbled ourselves from time to time to unjust demands until our children cry for bread. A company that knows all this, we should ask in the name of high heaven what more do they want -- our blood? They can get our lives. We are willing to sacrifice them, not for the company, but for our rights. Call out your armed hosts if you want them. Shield yourselves if you can, and remember that no foe, however dreaded, can repel us for a moment. Our determination may seem frail, but let it come. They may think our cause is weak. Fifteen thousand noble miners, who have been insulted and put upon by this self same company, are at our backs. The merchants and community at large along the whole line of the roads are on our side, and the working classes of every State in the Union are in our favor, and we feel confident that the God of the poor and the oppressed of the earth is with us. Therefore let the clashing of arms be heard; let the fiery elements be poured out if they think it right, but in heed of our right and in defence of our families, we shall conquer or we shall die.[29]

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

Keyser's growth accelerated in the 1880s, with the end of the Long Depression, through the turn of the century. The first high school opened in 1885. The first bank in town, the National Bank of Keyser, was chartered in 1886. A town water system was built in 1892, as was the first telephone line, connecting Keyser to Burlington, West Virginia. The Keyser Light and Power Company brought electricity to the town in 1895. A fire department, the Vigilant Reel and Hose Company No. 1, was organized in 1896. The Hoffman Hospital opened in 1904, as did the Preparatory School, which would later become Potomac State College. Both of these were located on Fort Hill, the site of Fort Fuller during the Civil War. A natural gas system powered street lamps and provided heating beginning in 1905.[41] An ornate music hall opened for entertainment.

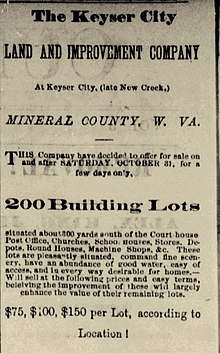

In these years, a prominent citizen of Keyser was Thomas R. Carskadon. He had been a shareholder of the Keyser Land and Improvement Company that sold the plots that would become much of downtown Keyser. In 1888, Carskadon ran for governor of West Virginia on the Prohibition Party ticket. A newspaper article described his pro-temperance views as unpopular yet voters liked to listen to his "characteristic, sound, humorous, eloquent, and happy speeches, which held his audience spellbound to the close."[42] In 1900, Carskadon put his name in the mix for Vice President on the Prohibition ticket but failed to win the nomination at the national convention.[43] Later that year, he ran again for Governor of West Virginia.[44]

All of the aforementioned infrastructure improvements attracted more industry, and Keyser's private sector began to diversify beyond its sometimes problematic dominant employer, the Baltimore & Ohio. Besides the B&O, railroad workers were now employed by the Western Maryland Railroad and the West Virginia Central Railroad, started by the Davis brothers and their in-law Senator Stephen Elkins in the 1880s.[45] The Keyser Woolen Mills began operations in 1893.[46] Rees' tannery operated on New Creek.[47] In 1905, the Keyser Pottery Company began firing its kilns along the Potomac River, producing decorative and bathroom ceramics.[48]

In 1903, another woolen mill, specializing in worsted wool, was opened on the banks of the Potomac in the shadow of Queens Point.[49] It was the women of Keyser who largely worked the machines here. A 1906 story reported: "A number of the girls employed at the Patchett Worsted Company are on a strike for higher wages this week."[50] In the early 1920s, the mill employed 200 workers, 175 of whom were women.[51] In later years, sometime before 1946, the workers voted to join Textile Workers Union of America Local 1874, the same local that organized workers at the much larger Celanese plant near Cumberland.[52]

As Keyser's industry boomed, so did its population. The need for labor was ravenous. European immigrants made their way to Keyser. The largest group of foreign-born Keyser residents in this era was the Italians, followed by the Irish.[53] In 1910, a single quarry operation near Keyser alone housed dozens of Italian men in its boarding facilities.[54] News of jobs traveled through family and village networks. Many of the Italians settling in Keyser and nearby Piedmont therefore hailed from the same Calabrian village, Caulonia. A restrictive national immigration law enacted in 1924 had at least two significant effects on Keyser. First, while the town's population had more than doubled between 1900 and 1920, in the following decade the population leveled out, despite being the Roaring Twenties.[55] Second, descendants of Keyser's Italian families have a disproportionate number of relatives in Adelaide, Australia. When the U.S. all but closed its gates to Italians in 1924, the village networks led Cauloniesi to emigrate to Adelaide.[56] The same Italian family names found in Keyser and Piedmont can be found in this south Australian city.

On February 3, 1913, the West Virginia legislature granted Keyser a charter designating it the "City of Keyser". The legislation consolidated Keyser with South Keyser and added further territory to the newly chartered city. Until this time, Keyser had functioned under a general law applicable to all municipalities in West Virginia. Its size now justified a special city charter from the state. The charter laid out Keyser's form of government as well.[57]

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the patriotic fervor of Keyser nearly caused another change in the town's name. Because "Keyser" was pronounced like "Kaiser," the title of the German leader, townsfolk began to tire of snide remarks from outsiders whenever they heard someone was from "Keyser". A campaign to change the name began in earnest. Proposals included Wilson (after the then-President), Pershing (after the then-general), Paddy Town (the original name), McPherson (a Civil War figure), and Fairfax-on-the-Potomac (harkening back to the original land grant). A Keyser soldier and local musician, Gene Cross, heard of the debate while enlisted and wrote a letter to the town newspaper that effectively ended the debate:

When the name Keyser appears before the mind's eye, all that we hold dear at once confronts us: the old Potomac, New Creek valley, the old B&O, Prep Hill, hospital, and all the dear old memories that surround it, and the greatest of all "Her People." By robbing the town of that name, you rob her of all these things to a certain extent, because when you think of the name, all these things flash across one's mind ... There is lots of good work that these people could use their spare time, energy, and brain power that needs attention far more than this question. So for the sake of the boys who are away from home and the ones who are going, let the old name stand. As we are looking forward to the time when all this international trouble will have passed away and we can come back to, not Wilson, Paddy Town, Pershing or any other, but Keyser, our boyhood Keyser.

In 1924, Keyser experienced its wettest year since 1889, and the Potomac River swelled over its banks twice in March. These massive floods brought widespread damage to homes and businesses in the north end of Keyser especially.

From Great Depression to Post-War Boom

Keyser's experience of the Great Depression in the 1930s was like any other small industrial city in the United States. Jobs were lost. Factories, like the Keyser Pottery Company, closed. Even the Baltimore & Ohio repair shops were closed for an entire year due to the slump, between 1932 and 1933.[58] New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) generated jobs for the unemployed. "W.P.A." stamps may still be seen on sidewalks constructed by this program in Keyser.

The Depression lifted as World War II began. The war efforts helped. For example, in January 1942, one month after the declaration of war, an entrepreneur from Brooklyn bought the worsted woolen mill with an aim of filling army contracts and ramped up production and employment.[59]

After the war, Keyser experienced another boom in industry. When the woolen mill closed in 1948, moving its equipment to India, the community pulled together to lure a new business to take over the facility.[60] When a firm expressed interest, four Keyser service clubs—the Lions, Kiwanis, Rotary, and Yeoman—started a campaign to sell $100 notes to purchase the plant for the firm. They raised $60,000 in 24 hours in October 1952.[61] California-based Pryne and Company was the beneficiary, taking over the plant to produce electric fans in Keyser.[62] Pryne was later bought by Emerson, which moved the plant to Bennettsville, South Carolina, in 1965. The site was not empty for long. A new owner soon took over, Penn Ventilator, which produced louvers and ventilators for heating and air conditioning systems. During these baby boom years, Keyser also featured two clothing factories, the Keyser Garment Company and the So Rite Lingerie Company.[63] Other manufacturing concerns included an Anchor Glass plant and the Flex-O-Lite mill, which produced Blastolite beads.[64]

In 1950, the Red Scare came to Keyser. That year, nearby Cumberland, Maryland, and Ridgeley, West Virginia, enacted ordinances requiring communists to register with the city. The Keyser American Legion post passed a motion for Keyser to do the same. The post commander said that several of his members said "they knew of Communists in Keyser and of Communist meetings."[65] At the time, the Cumberland ordinance was under legal challenge and was ruled unconstitutional a few months later, apparently causing the Keyser efforts to be abandoned.[66]

Following the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Keyser schools began integrating in the 1955–56 school year. That fall, students between grades 7 and 12 were integrated. Mineral County's school board, however, said younger students could not be integrated yet due to lack of classroom space. African-American children up to grade 6 continued to attend a segregated red brick school called Lincoln School on Church Street in Keyser.[67] They were integrated with white students within the next two years, when Lincoln School was renovated to house the Mineral County Board of Education in the late 1950s. Later, the building became the Keyser Senior Center at 30 Church Street.[68]

High employment and rising wages marked the 1950s and 1960s. Keyser's population peaked in the 1970 census.

Deindustrialization

Keyser's 20th Century economy relied heavily on manufacturing and the railroad. The economic crises of the 1970s and early 1980s hit the town hard. Plants in nearby cities where Keyser residents may have commuted took the early hits. Brewery, glass, textile, and tire plants in Cumberland, Maryland, especially began to close. The loss of income reverberated through the area economy, affecting retailers and other ancillary concerns. Globalization sent firms in search of cheap labor. By the 1980s, corporate raiders took their toll on employment, ultimately forcing the closure of a major tire plant, Kelly-Springfield, in Cumberland.

Many Keyser factories held on longer than the larger concerns in Cumberland, while reducing headcounts throughout this period. Eventually, however, one by one, they too began to close. In 1990, the Flex-O-Lite plant closed. The owners - the Lukens Company - claimed it was no longer profitable with high natural gas prices and "antiquated equipment." Laid off workers represented by the Aluminum, Brick and Glass International Union protested outside the plant when the company offered only $100 in severance pay for each year of service.[69] The Lukens Company made record-breaking profits that year, to the tune of $44.1 million.[70]

In 1995, both the Penn Ventilator and Anchor Glass plants closed. Many blamed this pair of closures on the North American Free Trade Agreement, which went into effect a year earlier.[71] For Penn Ventilator, the company, like Lukens, blamed old equipment, saying it would cost $7 million to upgrade the plant and "there were no concessions the local union or management could have made that would make us competitive."[72] For Anchor Glass, the company cited the very same problem: upgrades would be too costly.[73] Refusing to make the necessary capital investments, both companies shifted their operations elsewhere. In 1997, after a troubled attempt to save it through an employee stock ownership program, the Keyser Garment Company closed.[74] While Keyser's fortunes often rose and fell with the national economy through the centuries, the town did not experience the 1990s economic boom in the same way as other parts of the country.

21st Century

Today Keyser's population has largely stabilized. Since losing much of its manufacturing base, the town has found employment via health care, education, and service jobs. Potomac State College has continued to develop and is associated with West Virginia University. A new modern hospital and high school were opened.

With B&O and its roundhouse and repair shops long gone, the railroad through Keyser is now operated by CSX.

The Thomas R. Carskadon House and Mineral County Courthouse are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[75]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.92 square miles (4.97 km2), all land.[76] It is situated in a valley on the south side of the North Branch of the Potomac River at its junction with New Creek. New Creek forms most of the eastern boundary of the town. On the immediate eastern bank of New Creek is New Creek Mountain, peaking at 1,552 feet above sea level on the eastern side of Keyser (though the long mountain itself has higher peaks far south of Keyser). On Keyser's western edge is the Allegheny Front, rising 2,631 feet above sea level at this point along its range. The northern edge of Keyser is bounded by the North Branch of the Potomac River. Immediately across the river, in McCoole, Maryland, another portion of the New Creek Mountain ridge features a massive outcropping of Oriskany or Ridgeley sandstone known as Queens Point, a popular cliff from which to take in views of Keyser. The cliff is approximately 400 feet above the river.[77] The southern edge of Keyser is not bound by geology, as the valley here stretches further south than the city limits. Beyond its southern limits is the unincorporated community of New Creek.

Today, Keyser's western horizon is dotted with wind turbines. The NedPower Mount Storm Wind Farm began construction in 2006, installing 132 wind turbines atop the Allegheny Front, many of them overlooking Keyser.[78] Eventually, the wind farm reached 162 turbines, making it the largest east of the Mississippi.[79]

Keyser's oldest section is its downtown with the 1868 courthouse and two main commercial streets: Main and Armstrong. Armstrong runs parallel to the CSX (formerly B&O) railroad tracks, across which is a neighborhood known as the North End, sandwiched between the tracks and the river, where homes were constructed beginning in the late 1910s. Not far from downtown is Fort Hill, a small hill in the center of the city crowned with the campus of Potomac State College. The south end of Keyser features a relatively newer neighborhood, on the west side of U.S. Route 220, with most of the homes built in the 1960s and 1970s, known as Airport Addition, as it was once the site of a small airfield. An area sandwiched between Airport Addition and Potomac State College is known as "Radical Hill," which was the name of Thomas Carskadon's farm in the same location, so named by Carskadon because of his self-described radical opinions.[80] The most recent commercial development for the city has been south of the city, where shopping centers, a hotel, the new high school, and the new hospital have been constructed in recent years.

The main thoroughfares for the city are U.S. Route 220 and West Virginia Route 46. U.S. Route 220 eventually intersects with U.S. Route 50 south of Keyser. At its north end, 220 crosses the Potomac via newly reconstructed Memorial Bridge, heading toward Cumberland, Maryland. West Virginia Route 46 enters the east side of Keyser from the direction of Fort Ashby, West Virginia, becoming Armstrong Street and then West Piedmont Street before continuing on to Piedmont, West Virginia.

Geology

The type locality of the Silurian/Devonian Keyser Formation, a limestone, is located in a quarry and roadcut east of the town.

Transportation

_at_Maryland_Street_in_Keyser%2C_Mineral_County%2C_West_Virginia.jpg)

Keyser is served by two primary highways. The most prominent of these is U.S. Route 220. From Keyser, US 220 heads north, crosses the North Branch Potomac River into Allegany County, Maryland, and continues to Cumberland and points north. Heading south, US 220 heads through Moorefield and Petersburg before crossing into Virginia. The other primary highway serving Keyser is West Virginia Route 46. From Keyser, WV 46 heads west to Piedmont and Elk Garden while to the east, WV 46 extends to Fort Ashby.

Government

Keyser's government is headed by a mayor and five-member city council. Each serves four-year, staggered terms. The mayor and two council members are elected at one election, with the remaining three council members elected two years later. Elections are held on the second Tuesday in June of even-numbered years.[81] Originally, terms were only two years long, with staggered terms and elections held every June.

Two of Keyser's longest serving mayors were John C. Freeland (1894-1967) and Irving T. Athey (1922-1997). Except for a two-year break in the 1950s due to a reelection defeat, Freeland served as mayor from 1937 until 1957.[82] Athey was first elected in 1973 and had stints as mayor until health issues forced him to resign in 1990.[83]

Economy

As of 2016, approximately 11% of Keyser workers were employed in manufacturing jobs in or around Keyser. Another 20% worked in health care or personal care and service. A little less than 20% worked in sales and food service. Some 17% worked in a combination of education, training, administrative, and social service. The remainder of the workforce was spread across trucking, management, maintenance and repair, and other industries.[84] The poverty rate in Keyser was 27.4%. Its median household income was $28,378.[85]

The largest employers for Keyser residents include:

- Orbital ATK, which operates Allegany Ballistics Laboratory in nearby Rocket Center, West Virginia, producing rocket motors, warheads, and fuses for the military, with more than 500 employees.

- Potomac Valley Hospital, with more than 200 employees.

- Wal-Mart Stores, with more than 200 employees.

- Potomac State College of West Virginia University, with more than 100 employees.

- Mineral County Board of Education, with more than 100 employees.

- Heartland Employment Services, which operates a nursing home, with more than 100 employees.

- Automated Packaging Systems, which manufactures bag packaging systems, with more than 100 employees.

- West Virginia Department of Highways, with more than 100 employees.

- Information Manufacturing Inc., with more than 100 employees.

- Lumber and Things, which manufactures wooden pallets and skids, with more than 100 employees.[86]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 1,693 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,165 | 27.9% | |

| 1900 | 2,563 | 18.4% | |

| 1910 | 3,705 | 44.6% | |

| 1920 | 6,003 | 62.0% | |

| 1930 | 6,248 | 4.1% | |

| 1940 | 6,177 | −1.1% | |

| 1950 | 6,347 | 2.8% | |

| 1960 | 6,192 | −2.4% | |

| 1970 | 6,586 | 6.4% | |

| 1980 | 6,569 | −0.3% | |

| 1990 | 5,870 | −10.6% | |

| 2000 | 5,303 | −9.7% | |

| 2010 | 5,439 | 2.6% | |

| Est. 2019 | 4,915 | [3] | −9.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[87] | |||

.jpg)

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 5,439 people, 2,224 households, and 1,253 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,832.8 inhabitants per square mile (1,093.8/km2). There were 2,525 housing units at an average density of 1,315.1 per square mile (507.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.4% White, 8.6% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 2.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.4% of the population.

There were 2,224 households, of which 26.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.6% were married couples living together, 14.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.7% were non-families. 37.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.20 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 36.1 years. 19.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 19% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 19.8% were from 25 to 44; 24.7% were from 45 to 64; and 17.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.2% male and 51.8% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 5,303 people, 2,241 households, and 1,333 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,791.7 people per square mile (1,077.6/km2). There were 2,542 housing units at an average density of 1,338.2 per square mile (516.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.55% Euro American, 7.07% Black, 0.40% Asian, 0.32% from other races, and 1.43% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.72% of the population.

There were 2,241 households, out of which 24.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.3% were married couples living together, 13.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.5% were non-families. 36.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.19 and the average family size was 2.85.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 20.0% under the age of 18, 13.5% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 21.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,718, and the median income for a family was $32,708. Males had a median income of $29,034 versus $20,818 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,813. About 16.3% of families and 18.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 34.2% of those under age 18 and 11.0% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Keyser is the home of the Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a junior college that serves primarily as a feeder college to WVU's main campus in Morgantown.

Keyser's public schools are part of the Mineral County school system. The schools in Keyser include Keyser Primary School and Fountain Primary School, which cover Pre-Kindergarten through fifth grade; Keyser Middle School, which covers sixth through eighth grade; Keyser High School, which covers ninth through twelfth grades; Mineral County Alternative School; and the Mineral County Tech Center, a vocational school.[88] The mascot of Keyser High is the "Golden Tornado."

Media

The city and surrounding county are served by a daily newspaper, the Mineral Daily News-Tribune.

Three radio stations broadcast in Keyser: WQZK 94.1 FM (Top 40), WKYW 102.9 FM (Folk), and WKLP 1390 AM (Sports).

Notable people

- William Armstrong (1782–1865) – United States representative from Virginia. Died in Keyser.[89]

- Woodrow Wilson Barr (1918–1942) – World War II soldier awarded the Silver Star posthumously; born in Keyser

- Henry Louis Gates Jr. (b. 1950) – Historian, author, academic; born in Keyser[90]

- Jonah Edward Kelley (1923–1945) – World War II soldier awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously; raised in Keyser

- John Kruk (b. 1961) – Major League Baseball player, ESPN baseball analyst; raised in Keyser

- Pete Ladygo (1928–2014) – American/Canadian football player for the Pittsburgh Steelers and Ottawa Rough Riders

- Frank Lovece – Journalist, author, comics writer; lived there in childhood[91]

- Catherine Marshall (1914–1983) – American author known for her inspirational works, notably the novel Christy; raised in Keyser

- Leo Mazzone (b. 1948) – Major League Baseball pitching coach; born in Keyser

- Walter E. Rollins (1906–1973), (also known as Jack Rollins) – Songwriter who wrote "Frosty the Snowman" and "Smokey Bear"

- Harley Orrin Staggers (1907–1991) – United States Congressman; born in Keyser

In popular culture

Keyser is mentioned in the BBC television mini series The State Within (Season 1, Episode 1). British Ambassador Mark Brydon just landed from a round trip to the U.K. where he was told he will be nominated to a new position in the British Government. En route to the embassy, a plane that just departed explodes above the highway, killing all the passengers and a few people on the highway. Rapidly, the Secret Services pinpoint that it is a terrorist bombing and that the terrorist was of British nationality. British SAS are shown on a raid, the screen clearly labels the location "Keyser, West Virginia." One of their members is killed in a shoot out and dumped in a nearby stream located in the fictitious "Fairmont County, West Virginia." [92]

Keyser is mentioned extensively in Colored People, a 1994 memoir by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Keyser is featured as a location to hunt Whitetail Deer in a few versions of the Big Buck Hunter video game.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Kenny, Hamill (1945). West Virginia Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning, Including the Nomenclature of the Streams and Mountains. Piedmont, WV: The Place Name Press. p. 349.

- O'Brien, Michael J. (1921). The McCarthy's in Early American History. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 92–93.

- "Salt in Coal Regions". Clarksburg Register. December 3, 1851.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keyprint, Inc. p. 4.

- Beavers, Liz (October 8, 2015). "Genealogical Society to celebrate McCarty Stone House". Mineral Daily News-Tribune.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 5.

- "To the Editors of the National Intelligencer". National Intelligencer. November 23, 1833.

- Industrial History of the Potomac's Quartette of Towns. Piedmont, WV: Industrial Publishing Company. 1906.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 8.

- Industrial History of the Potomac's Quartette of Towns. Piedmont, WV: Industrial Publishing Company. 1906.

- Boggs, Mara (Winter 2015). "Living in Keyser". WV Living.

- Swick-Cruse, Deborah "Keyser." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 31 May 2013. Web. 04 April 2017. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1198

- Industrial History of the Potomac's Quartette of Towns. Piedmont, WV: Industrial Publishing Company. 1906.

- "The Brook's Gap Rifles". Rockingham Register and Advertiser. August 2, 1861.

- "The Occupation of New Creek of Doubtful Expediency". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. June 19, 1863.

- "Rebel Raid upon New Creek - A Government Train Captured". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. January 6, 1864.

- "A Rebel Raid on New Creek, Va. - Destruction of the Place". Philadelphia Inquirer. November 30, 1864.

- "More About the Late New Creek Raid". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. December 7, 1964.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 20.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 20.

- Industrial History of the Potomac's Quartette of Towns. Piedmont, WV: Industrial Printing Company. 1906.

- Wolfe, William W. (1974). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. pp. 22–23.

- "Corporation Election in Keyser". Cumberland Daily Times. January 11, 1875.

- Stowell, David O. (2008). The Great Strikes of 1877. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 2–3.

- Bellesiles, Michael A. (2010). "1877: America's Year for Living Violently. The New Press, 2010. p 149. https://books.google.com/books?id=rf4q5LjLbHIC&pg=PA149 Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Caplinger, Michael (2003). "The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Martinsburg Shops NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION" (PDF). pp. 40–45.

- Foner, Philip S. (1977). The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. New York: Pathfinder. p. 44.

- "The Railroad Strike". The Boston Daily Globe. July 18, 1877.

- Foner, Philip S. (1977). The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. New York: Pathfinder. p. 53.

- "The Men Standing Firm at Keyser". Philadelphia Times. July 20, 1877.

- "The Trouble at Keyser Overcome". Philadelphia Inquirer. July 30, 1877.

- "The Situation Elsewhere". Cumberland Alleganian. July 31, 1877.

- "Events at Keyser, West Virginia". Baltimore Sun. August 1, 1877.

- Foner, Philip S. (1977). The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. New York: Pathfinder. p. 63.

- Wolfe, William W. (1977). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 27.

- "The Prohibition Blowout". Cumberland Daily Times. September 24, 1888.

- "Personal Mention". Cumberland Evening Times. July 4, 1900.

- "Random Notes". Muscatine Journal (Iowa). November 1, 1900.

- Wolfe, William W. (1977). History of Keyser, West Virginia, 1737-1913. Keystone Print, Inc. p. 27.

- "The Keyser Woolen Mills". Keyser Tribune. July 1898.

- Clites Sr., Gary (2015). Forgotten But Not Gone. Knobley Mountain Press. p. 73.

- Clites Sr., Gary (2015). Forgotten But Not Gone. Knobley Mountain Press. p. 81.

- "New Woolen Mill". The Cumberland Alleganian. April 30, 1903.

- "West Va. News: Keyser". Cumberland Evening Times. June 15, 1906.

- Daugherty, G.F. (1922). Sixteenth Biennial Report of the Bureau of Labor of West Virginia, 1921-22. p. 97.

- "Keyser Workers Ask Pay Boost". Cumberland Times. December 1, 1946.

- Review of 1920 United States Census, Keyser, Mineral, West Virginia; Roll: T625_1964.

- 1910 U.S. Federal Census, New Creek, Mineral, West Virginia, Roll T624 1690, Page 12A, Enumeration Dist. 0063, Image 785, FHL No. 1375703.

- See historical population chart on this page.

- Cosmini-Rose, Daniela (2008). Caulonia in the Heart. Lythrum Press.

- "Keyser's New Charter". Cumberland Evening Times. February 27, 1913.

- "Work Resumes in Shops". Cumberland Times. June 4, 1933.

- "Keyser Worsted Mill Purchased by A. Rubinstein, Brooklyn, N.Y.". The Cumberland News. January 29, 1942.

- "Keyser Mill to Halt Work". Cumberland Evening Times. November 24, 1948.

- "Keyser's Plant Fund Reaches $60,000 Total". Cumberland News. October 27, 1952.

- "Keyser to Seek $45,000 Fund for Industry". The Cumberland News. October 23, 1952.

- "Keyser Area Plants Plan Expansion". The Cumberland Evening Times. June 12, 1958.

- "Machinery Ordered for Keyser Plant". The Cumberland News. January 23, 1967.

- "Motion asks action against communists". Cumberland Evening Times. September 22, 1950.

- "Court invalidates anti-communist law". Cumberland News. January 26, 1951.

- "Integration will begin in Mineral County". Cumberland News. July 9, 1955.

- Ridder, Mona (November 30, 2003). "School buildings good for business". Cumberland Times-News.

- "Former Flex-O-Lite employees protest". Cumberland Times-News. August 2, 1990.

- "Lukens Inc. - Company Profile".

- "Plant's Loss Fueling Fears for Economy". Cumberland Times-News. January 29, 1996.

- "Keyser Plant to Close after 28 Years". New Bern Sun Journal. March 29, 1995.

- "Authority keeps business in place". Cumberland Times-News. January 24, 1996.

- "Former garment workers say firm kept them in dark". Cumberland Times-News. December 8, 1997.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- Kindle, E.M. (1912). Bulletin 508: The Onondaga Fauna of the Allegheny Region. Washington: United States Geological Survey. p. 38.

- "Mount Storm Wind Project Behind Schedule". Cumberland Times-News. March 8, 2008.

- "NedPower - About".

- "Radical Hill Mansion".

- "City of Keyser Government".

- "John C. Freeland Service Set Today". Cumberland News. October 30, 1967.

- "Keyser Mayor Resigns Because of Health". Cumberland Times-News. May 2, 1990.

- "Data USA: Keyser, WV".

- "Data USA: Keyser, WV".

- "West Virginia Department of Commerce - Mineral County".

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Mineral County Schools".

- William Armstrong at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on November 18, 2015.

- Hale, Dorothy J. (9 February 2009). The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900-2000. John Wiley & Sons. p. 511. ISBN 978-1-4051-5107-8.

- Abrams, Nancy (September 10, 1989). "Frank Lovece Makes a Living Writing About TV". The Dominion Post. Morgantown, West Virginia. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- "The State Within - Episodes". BBC.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keyser, West Virginia. |

- City of Keyser (website)

- Full Text of The McCarthy's in Early American History (concerning the McCarty's who settled Paddy Town)

- "Keyser a Strategic Stronghold during Civil War," Cumberland Times-News

- Keyser High School

- Full text of History of Keyser, West Virginia by William W. Wolfe (1974)