Tunisia

Tunisia,[lower-alpha 1] officially the Republic of Tunisia,[lower-alpha 2][18] is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa, covering 163,610 square kilometres (63,170 square miles). Its northernmost point, Cape Angela, is also the northernmost point on the African continent. Tunisia is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia's population was 11.7 million in 2019.[12] Tunisia's name is derived from its capital city, Tunis (Berber native name: Tunest), which is located on its northeast coast.

Republic of Tunisia | |

|---|---|

Motto: حرية، كرامة، عدالة، نظام "Ḥurrīyah, Karāma, 'Adālah, Niẓām" "freedom, dignity, justice, and order"[1] | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tunis 36°49′N 10°11′E |

| Official languages | Arabic[2] |

| Spoken languages | |

| Ethnic groups | Arab-Berber 98%, European 1%, Jewish and other 1%[8] |

| Religion | Islam[9] |

| Demonym(s) | Tunisian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic[10][11] |

| Kais Saied | |

| Elyes Fakhfakh | |

| Rached Ghannouchi | |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Representatives of the People |

| Formation | |

• Husainid Dynasty inaugurated | 15 July 1705 |

• Independence from France | 20 March 1956 |

| 25 July 1957 | |

| 7 November 1987 | |

| 14 January 2011 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 163,610 km2 (63,170 sq mi) (91st) |

• Water (%) | 5.0 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 11,722,038[12] (78th) |

• Density | 71/km2 (183.9/sq mi) (133rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | 35.8[14] medium |

| HDI (2018) | high · 91st |

| Currency | Tunisian dinar (TND) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +216 |

| ISO 3166 code | TN |

| Internet TLD | |

Geographically, Tunisia contains the eastern end of the Atlas Mountains, and the northern reaches of the Sahara desert. Much of the rest of the country's land is fertile soil. Its 1,300 kilometres (810 miles) of coastline include the African conjunction of the western and eastern parts of the Mediterranean Basin.

Tunisia is a unitary semi-presidential representative democratic republic. It is considered to be the only fully democratic sovereign state in the Arab world.[19][20] It has a high human development index.[15] It has an association agreement with the European Union; is a member of La Francophonie, the Union for the Mediterranean, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the Arab Maghreb Union, the Arab League, the OIC, the Greater Arab Free Trade Area, the Community of Sahel–Saharan States, the African Union, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Group of 77; and has obtained the status of major non-NATO ally of the United States. In addition, Tunisia is also a member state of the United Nations and a state party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Close relations with Europe, in particular with France[21] and with Italy,[22][23] have been forged through economic cooperation, privatisation and industrial modernization.

In ancient times, Tunisia was primarily inhabited by Berbers. Phoenician immigration began in the 12th century BC; these immigrants founded Carthage. A major mercantile power and a military rival of the Roman Republic, Carthage was defeated by the Romans in 146 BC. The Romans occupied Tunisia for most of the next 800 years, introduced Christianity and left architectural legacies like the amphitheatre of El Jem. After several attempts starting in 647, Muslims conquered the whole of Tunisia by 697 and introduced Islam. After a series of campaigns beginning in 1534 to conquer and colonize the region, the Ottoman Empire established control in 1574 and held sway for over 300 years afterwards. French colonization of Tunisia occurred in 1881. Tunisia gained independence with Habib Bourguiba and declared the Tunisian Republic in 1957. In 2011, the Tunisian Revolution resulted in the overthrow of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, followed by parliamentary elections. The country voted for parliament again on 26 October 2014,[24] and for President on 23 November 2014.[25] As a result, Tunisia is the only country in North Africa classified as "Free" by the Freedom House organization[26] and is also considered by The Economist's Democracy Index as the only democracy in the Arab World.[27]

Etymology

The word Tunisia is derived from Tunis; a central urban hub and the capital of modern-day Tunisia. The present form of the name, with its Latinate suffix -ia, evolved from French Tunisie,[28] in turn generally associated with the Berber root ⵜⵏⵙ, transcribed tns, which means "to lay down" or "encampment".[29] It is sometimes also associated with the Punic goddess Tanith (aka Tunit),[28][30] ancient city of Tynes.[31][32]

The French derivative Tunisie was adopted in some European languages with slight modifications, introducing a distinctive name to designate the country. Other languages remained untouched, such as the Russian Туни́с (Tunís) and Spanish Túnez. In this case, the same name is used for both country and city, as with the Arabic تونس, and only by context can one tell the difference.[28]

Before Tunisia, the territory's name was Ifriqiya or Africa, which gave the present-day name of the continent Africa.

History

Antiquity

Farming methods reached the Nile Valley from the Fertile Crescent region about 5000 BC, and spread to the Maghreb by about 4000 BC. Agricultural communities in the humid coastal plains of central Tunisia then were ancestors of today's Berber tribes.

It was believed in ancient times that Africa was originally populated by Gaetulians and Libyans, both nomadic peoples. According to the Roman historian Sallust, the demigod Hercules died in Spain and his polyglot eastern army was left to settle the land, with some migrating to Africa. Persians went to the West and intermarried with the Gaetulians and became the Numidians. The Medes settled and were known as Mauri, later Moors.[33]

The Numidians and Moors belonged to the race from which the Berbers are descended. The translated meaning of Numidian is Nomad and indeed the people were semi-nomadic until the reign of Masinissa of the Massyli tribe.[34][35][36]

At the beginning of recorded history, Tunisia was inhabited by Berber tribes. Its coast was settled by Phoenicians starting as early as the 12th century BC (Bizerte, Utica). The city of Carthage was founded in the 9th century BC by Phoenicians. Legend says that Dido from Tyre, now in modern-day Lebanon, founded the city in 814 BC, as retold by the Greek writer Timaeus of Tauromenium. The settlers of Carthage brought their culture and religion from Phoenicia, now present-day Lebanon and adjacent areas.[37]

After the series of wars with Greek city-states of Sicily in the 5th century BC, Carthage rose to power and eventually became the dominant civilization in the Western Mediterranean. The people of Carthage worshipped a pantheon of Middle Eastern gods including Baal and Tanit. Tanit's symbol, a simple female figure with extended arms and long dress, is a popular icon found in ancient sites. The founders of Carthage also established a Tophet, which was altered in Roman times.

A Carthaginian invasion of Italy led by Hannibal during the Second Punic War, one of a series of wars with Rome, nearly crippled the rise of Roman power. From the conclusion of the Second Punic War in 202 BC, Carthage functioned as a client state of the Roman Republic for another 50 years.[38]

Following the Battle of Carthage which began in 149 BC during the Third Punic War, Carthage was conquered by Rome in 146 BC.[39] Following its conquest, the Romans renamed Carthage to Africa, incorporating it as a province.

During the Roman period, the area of what is now Tunisia enjoyed a huge development. The economy, mainly during the Empire, boomed: the prosperity of the area depended on agriculture. Called the Granary of the Empire, the area of actual Tunisia and coastal Tripolitania, according to one estimate, produced one million tons of cereals each year, one-quarter of which was exported to the Empire. Additional crops included beans, figs, grapes, and other fruits.

By the 2nd century, olive oil rivaled cereals as an export item. In addition to the cultivations and the capture and transporting of exotic wild animals from the western mountains, the principal production and exports included the textiles, marble, wine, timber, livestock, pottery such as African Red Slip, and wool.

1.jpg)

There was even a huge production of mosaics and ceramics, exported mainly to Italy, in the central area of El Djem (where there was the second biggest amphitheater in the Roman Empire).

Berber bishop Donatus Magnus was the founder of a Christian group known as the Donatists.[40] During the 5th and 6th centuries (from 430 to 533 AD), the Germanic Vandals invaded and ruled over a kingdom in Northwest Africa that included present-day Tripoli. The region was easily reconquered in 533–534 AD, during the rule of Emperor Justinian I, by the Eastern Romans led by General Belisarius.[41]

Middle Ages

Sometime between the second half of the 7th century and the early part of the 8th century, Arab Muslim conquest occurred in the region. They founded the first Islamic city in Northwest Africa, Kairouan. It was there in 670 AD that the Mosque of Uqba, or the Great Mosque of Kairouan, was constructed.[42] This mosque is the oldest and most prestigious sanctuary in the Muslim West with the oldest standing minaret in the world;[43] it is also considered a masterpiece of Islamic art and architecture.[44]

Tunis was taken in 695, re-taken by the Byzantine Eastern Romans in 697, but lost finally in 698. The transition from a Latin-speaking Christian Berber society to a Muslim and mostly Arabic-speaking society took over 400 years (the equivalent process in Egypt and the Fertile Crescent took 600 years) and resulted in the final disappearance of Christianity and Latin in the 12th or 13th centuries. The majority of the population were not Muslim until quite late in the 9th century; a vast majority were during the 10th. Also, some Tunisian Christians emigrated; some richer members of society did so after the conquest in 698 and others were welcomed by Norman rulers to Sicily or Italy in the 11th and 12th centuries – the logical destination because of the 1200 year close connection between the two regions.[45]

The Arab governors of Tunis founded the Aghlabid dynasty, which ruled Tunisia, Tripolitania and eastern Algeria from 800 to 909.[46] Tunisia flourished under Arab rule when extensive systems were constructed to supply towns with water for household use and irrigation that promoted agriculture (especially olive production).[46][47] This prosperity permitted luxurious court life and was marked by the construction of new palace cities such as al-Abassiya (809) and Raqadda (877).[46]

After conquering Cairo, the Fatimids abandoned Tunisia and parts of Eastern Algeria to the local Zirids (972–1148).[48] Zirid Tunisia flourished in many areas: agriculture, industry, trade, and religious and secular learning.[49] Management by the later Zirid emirs was neglectful though, and political instability was connected to the decline of Tunisian trade and agriculture.[46][50][51]

The depredation of the Tunisian campaigns by the Banu Hilal, a warlike Arab Bedouin tribe encouraged by the Fatimids of Egypt to seize Northwest Africa, sent the region's rural and urban economic life into further decline.[48] Consequently, the region underwent rapid urbanisation as famines depopulated the countryside and industry shifted from agriculture to manufactures.[52] The Arab historian Ibn Khaldun wrote that the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become completely arid desert.[50][53]

The main Tunisian cities were conquered by the Normans of Sicily under the Kingdom of Africa in the 12th century, but following the conquest of Tunisia in 1159–1160 by the Almohads the Normans were evacuated to Sicily. Communities of Tunisian Christians would still exist in Nefzaoua up to the 14th century.[54] The Almohads initially ruled over Tunisia through a governor, usually a near relative of the Caliph. Despite the prestige of the new masters, the country was still unruly, with continuous rioting and fighting between the townsfolk and wandering Arabs and Turks, the latter being subjects of the Muslim Armenian adventurer Karakush. Also, Tunisia was occupied by Ayyubids between 1182 and 1183 and again between 1184 and 1187.[55]

The greatest threat to Almohad rule in Tunisia was the Banu Ghaniya, relatives of the Almoravids, who from their base in Mallorca tried to restore Almoravid rule over the Maghreb. Around 1200 they succeeded in extending their rule over the whole of Tunisia until they were crushed by Almohad troops in 1207. After this success, the Almohads installed Walid Abu Hafs as the governor of Tunisia. Tunisia remained part of the Almohad state, until 1230 when the son of Abu Hafs declared himself independent. During the reign of the Hafsid dynasty, fruitful commercial relationships were established with several Christian Mediterranean states.[56] In the late 16th century the coast became a pirate stronghold.

Ottoman Tunisia

In the last years of the Hafsid dynasty, Spain seized many of the coastal cities, but these were recovered by the Ottoman Empire.

The first Ottoman conquest of Tunis took place in 1534 under the command of Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha, the younger brother of Oruç Reis, who was the Kapudan Pasha of the Ottoman Fleet during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. However, it was not until the final Ottoman reconquest of Tunis from Spain in 1574 under Kapudan Pasha Uluç Ali Reis that the Ottomans permanently acquired the former Hafsid Tunisia, retaining it until the French conquest of Tunisia in 1881.

Initially under Turkish rule from Algiers, soon the Ottoman Porte appointed directly for Tunis a governor called the Pasha supported by janissary forces. Before long, however, Tunisia became in effect an autonomous province, under the local Bey. Under its Turkish governors, the Beys, Tunisia attained virtual independence. The Hussein dynasty of Beys, established in 1705, lasted until 1957.[57] This evolution of status was from time to time challenged without success by Algiers. During this era the governing councils controlling Tunisia remained largely composed of a foreign elite who continued to conduct state business in the Turkish language.

Attacks on European shipping were made by corsairs, primarily from Algiers, but also from Tunis and Tripoli, yet after a long period of declining raids the growing power of the European states finally forced its termination. Under the Ottoman Empire, the boundaries of Tunisia contracted; it lost territory to the west (Constantine) and to the east (Tripoli).

The plague epidemics ravaged Tunisia in 1784–1785, 1796–1797 and 1818–1820.[58]

In the 19th century, the rulers of Tunisia became aware of the ongoing efforts at political and social reform in the Ottoman capital. The Bey of Tunis then, by his own lights but informed by the Turkish example, attempted to effect a modernizing reform of institutions and the economy.[59] Tunisian international debt grew unmanageable. This was the reason or pretext for French forces to establish a protectorate in 1881.

French Tunisia (1881–1956)

In 1869, Tunisia declared itself bankrupt and an international financial commission took control over its economy. In 1881, using the pretext of a Tunisian incursion into Algeria, the French invaded with an army of about 36,000 and forced the Bey to agree to the terms of the 1881 Treaty of Bardo (Al Qasr as Sa'id).[60] With this treaty, Tunisia was officially made a French protectorate, over the objections of Italy. Under French colonization, European settlements in the country were actively encouraged; the number of French colonists grew from 34,000 in 1906 to 144,000 in 1945. In 1910 there were 105,000 Italians in Tunisia.[61]

During World War II, French Tunisia was ruled by the collaborationist Vichy government located in Metropolitan France. The antisemitic Statute on Jews enacted by the Vichy was also implemented in Vichy Northwest Africa and overseas French territories. Thus, the persecution, and murder of the Jews from 1940 to 1943 was part of the Shoah in France.

From November 1942 until May 1943, Vichy Tunisia was occupied by Nazi Germany. SS Commander Walter Rauff continued to implement the Final Solution there. From 1942–1943, Tunisia was the scene of the Tunisia Campaign, a series of battles between the Axis and Allied forces. The battle opened with initial success by the German and Italian forces, but the massive supply and numerical superiority of the Allies led to the Axis surrender on 13 May 1943.[62][63]

Post-independence (1956–2011)

Tunisia achieved independence from France on 20 March 1956 with Habib Bourguiba as Prime Minister.[64] 20 March is celebrated annually as Tunisian Independence Day.[65] A year later, Tunisia was declared a republic, with Bourguiba as the first President.[66] From independence in 1956 until the 2011 revolution, the government and the Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD), formerly Neo Destour and the Socialist Destourian Party, were effectively one. Following a report by Amnesty International, The Guardian called Tunisia "one of the most modern but repressive countries in the Arab world".[67]

In November 1987, doctors[68] declared Bourguiba unfit to rule and, in a bloodless coup d'état, Prime Minister Zine El Abidine Ben Ali assumed the presidency[66] in accordance with Article 57 of the Tunisian constitution.[69] The anniversary of Ben Ali's succession, 7 November, was celebrated as a national holiday. He was consistently re-elected with enormous majorities every five years (well over 80 percent of the vote), the last being 25 October 2009,[70] until he fled the country amid popular unrest in January 2011.

Ben Ali and his family were accused of corruption[71] and plundering the country's money. Economic liberalisation provided further opportunities for financial mismanagement,[72] while corrupt members of the Trabelsi family, most notably in the cases of Imed Trabelsi and Belhassen Trabelsi, controlled much of the business sector in the country.[73] The First Lady Leila Ben Ali was described as an "unabashed shopaholic" who used the state airplane to make frequent unofficial trips to Europe's fashion capitals.[74] Tunisia refused a French request for the extradition of two of the President's nephews, from Leila's side, who were accused by the French State prosecutor of having stolen two mega-yachts from a French marina.[75] Ben Ali's son-in-law Sakher El Materi was rumoured as being primed to eventually take over the country.[76]

Independent human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, Freedom House, and Protection International, documented that basic human and political rights were not respected.[77][78] The regime obstructed in any way possible the work of local human rights organizations.[79] In 2008, in terms of Press freedom, Tunisia was ranked 143rd out of 173.[80]

Post-revolution (since 2011)

.jpg)

The Tunisian Revolution[81][82] was an intensive campaign of civil resistance that was precipitated by high unemployment, food inflation, corruption,[83] a lack of freedom of speech and other political freedoms[84] and poor living conditions. Labour unions were said to be an integral part of the protests.[85] The protests inspired the Arab Spring, a wave of similar actions throughout the Arab world.

The catalyst for mass demonstrations was the death of Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old Tunisian street vendor, who set himself afire on 17 December 2010 in protest at the confiscation of his wares and the humiliation inflicted on him by a municipal official named Faida Hamdy. Anger and violence intensified following Bouazizi's death on 4 January 2011, ultimately leading longtime President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to resign and flee the country on 14 January 2011, after 23 years in power.[86]

Protests continued for banning of the ruling party and the eviction of all its members from the transitional government formed by Mohammed Ghannouchi. Eventually the new government gave in to the demands. A Tunis court banned the ex-ruling party RCD and confiscated all its resources. A decree by the minister of the interior banned the "political police", special forces which were used to intimidate and persecute political activists.[87]

On 3 March 2011, the interim president announced that elections to a Constituent Assembly would be held on 24 July 2011.[88] On 9 June 2011, the prime minister announced the election would be postponed until 23 October 2011.[89] International and internal observers declared the vote free and fair. The Ennahda Movement, formerly banned under the Ben Ali regime, came out of the election as the largest party, with 89 seats out of a total of 217.[90] On 12 December 2011, former dissident and veteran human rights activist Moncef Marzouki was elected president.[91]

In March 2012, Ennahda declared it will not support making sharia the main source of legislation in the new constitution, maintaining the secular nature of the state. Ennahda's stance on the issue was criticized by hardline Islamists, who wanted strict sharia, but was welcomed by secular parties.[92] On 6 February 2013, Chokri Belaid, the leader of the leftist opposition and prominent critic of Ennahda, was assassinated.[93]

In 2014, President Moncef Marzouki established Tunisia's Truth and Dignity Commission, as a key part of creating a national reconciliation.[94]

Tunisia was hit by two terror attacks on foreign tourists in 2015, first killing 22 people at the Bardo National Museum, and later killing 38 people at the Sousse beachfront. Tunisian president Beji Caid Essebsi renewed the state of emergency in October for three more months.[95]

The Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet won the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for its work in building a peaceful, pluralistic political order in Tunisia.[96]

Geography

Tunisia is situated on the Mediterranean coast of Northwest Africa, midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Nile Delta. It is bordered by Algeria on the west and southwest and Libya on the south east. It lies between latitudes 30° and 38°N, and longitudes 7° and 12°E. An abrupt southward turn of the Mediterranean coast in northern Tunisia gives the country two distinctive Mediterranean coasts, west–east in the north, and north–south in the east.

Though it is relatively small in size, Tunisia has great environmental diversity due to its north–south extent. Its east–west extent is limited. Differences in Tunisia, like the rest of the Maghreb, are largely north–south environmental differences defined by sharply decreasing rainfall southward from any point. The Dorsal, the eastern extension of the Atlas Mountains, runs across Tunisia in a northeasterly direction from the Algerian border in the west to the Cape Bon peninsula in the east. North of the Dorsal is the Tell, a region characterized by low, rolling hills and plains, again an extension of mountains to the west in Algeria. In the Khroumerie, the northwestern corner of the Tunisian Tell, elevations reach 1,050 metres (3,440 ft) and snow occurs in winter.

The Sahel, a broadening coastal plain along Tunisia's eastern Mediterranean coast, is among the world's premier areas of olive cultivation. Inland from the Sahel, between the Dorsal and a range of hills south of Gafsa, are the Steppes. Much of the southern region is semi-arid and desert.

Tunisia has a coastline 1,148 kilometres (713 mi) long. In maritime terms, the country claims a contiguous zone of 24 nautical miles (44.4 km; 27.6 mi), and a territorial sea of 12 nautical miles (22.2 km; 13.8 mi).[97]

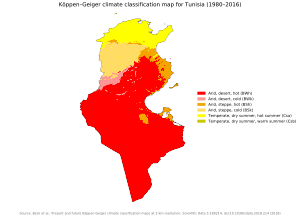

Climate

Tunisia's climate is Mediterranean in the north, with mild rainy winters and hot, dry summers.[98] The south of the country is desert. The terrain in the north is mountainous, which, moving south, gives way to a hot, dry central plain. The south is semiarid, and merges into the Sahara. A series of salt lakes, known as chotts or shatts, lie in an east–west line at the northern edge of the Sahara, extending from the Gulf of Gabes into Algeria. The lowest point is Chott el Djerid at 17 metres (56 ft) below sea level and the highest is Jebel ech Chambi at 1,544 metres (5,066 ft).[99]

| Climate data for Tunisia in general | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

23.0 (73.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19 (66) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 50.5 (1.99) |

45.3 (1.78) |

43.4 (1.71) |

35.5 (1.40) |

21 (0.8) |

10.8 (0.43) |

3.7 (0.15) |

8.8 (0.35) |

10.5 (0.41) |

38.6 (1.52) |

46.4 (1.83) |

56.4 (2.22) |

370.9 (14.59) |

| Source: Weatherbase[100] | |||||||||||||

Politics

|  |

| Kais Saied President since 2019 |

Elyes Fakhfakh Prime Minister since 2020 |

Tunisia is a representative democracy and a republic with a president serving as head of state, a prime minister as head of government, a unicameral parliament, and a civil law court system. The Constitution of Tunisia, adopted 26 January 2014, guarantees rights for women and states that the President's religion "shall be Islam". In October 2014 Tunisia held its first elections under the new constitution following the Arab Spring.[101] Tunisia (#69 worldwide) is the only democracy in North Africa.[102]

The number of legalized political parties in Tunisia has grown considerably since the revolution. There are now over 100 legal parties, including several that existed under the former regime. During the rule of Ben Ali, only three functioned as independent opposition parties: the PDP, FDTL, and Tajdid. While some older parties are well-established and can draw on previous party structures, many of the 100-plus parties extant as of February 2012 are small.[103]

Rare for the Arab world, women held more than 20% of seats in the country's pre-revolution bicameral parliament.[104] In the 2011 constituent assembly, women held between 24% and 31% of all seats.[105][106]

Tunisia is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer. On 23 November 2014 Tunisia held its first Presidential Election following the Arab Spring in 2011.[107]

The Tunisian legal system is heavily influenced by French civil law, while the Law of Personal Status is based on Islamic law.[108] Sharia courts were abolished in 1956.[108]

A Code of Personal Status was adopted shortly after independence in 1956, which, among other things, gave women full legal status (allowing them to run and own businesses, have bank accounts, and seek passports under their own authority). The code outlawed the practices of polygamy and repudiation and a husband's right to unilaterally divorce his wife.[109] Further reforms in 1993 included a provision to allow Tunisian women to transmit citizenship even if they are married to a foreigner and living abroad.[110] The Law of Personal Status is applied to all Tunisians regardless of their religion.[108] The Code of Personal Status remains one of the most progressive civil codes in North Africa and the Muslim world.[111]

Human rights

After the revolution, a number of Salafist groups emerged and in some occasions have violently repressed artistic expression that is viewed to be hostile to Islam.[112]

Since the revolution, some non-governmental organizations have reconstituted themselves and hundreds of new ones have emerged. For instance, the Tunisian Human Rights League, the first human rights organization in Africa and the Arab world, operated under restrictions and state intrusion for over half of its existence, but is now free to operate. Some independent organizations, such as the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women, the Association of Tunisian Women for Research and Development, and the Bar Association also remain active.[103]

Homosexuality is illegal in Tunisia and can be punished by up to three years in prison.[113] On 7 December 2016, two Tunisian men were arrested on suspicion of homosexual activity in Sousse.[114] According to 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 94% of Tunisians believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[115]

The Tunisian regime has been criticised for its policy on recreational drug use, for instance automatic 1-year prison sentences for consuming cannabis. Prisons are crowded and drug offenders represent nearly a third of the prison population.[116]

In 2017, Tunisia became the first Arab country to outlaw domestic violence against women, which was previously not a crime.[117] Also, the law allowing rapists to escape punishment by marrying the victim was abolished.[117] According to Human Rights Watch, 47% of Tunisian women have been subject to domestic violence.[118][119]

Military

As of 2008, Tunisia had an army of 27,000 personnel equipped with 84 main battle tanks and 48 light tanks. The navy had 4,800 personnel operating 25 patrol boats and 6 other craft. The Tunisian Air Force has 154 aircraft and 4 UAVs. Paramilitary forces consisted of a 12,000-member national guard.[120] Tunisia's military spending was 1.6% of GDP as of 2006. The army is responsible for national defence and also internal security. Tunisia has participated in peacekeeping efforts in the DROC and Ethiopia/Eritrea.[121] United Nations peacekeeping deployments for the Tunisian armed forces have been in Cambodia (UNTAC), Namibia (UNTAG), Somalia, Rwanda, Burundi, Western Sahara (MINURSO) and the 1960s mission in the Congo, ONUC.

The military has historically played a professional, apolitical role in defending the country from external threats. Since January 2011 and at the direction of the executive branch, the military has taken on increasing responsibility for domestic security and humanitarian crisis response.[103]

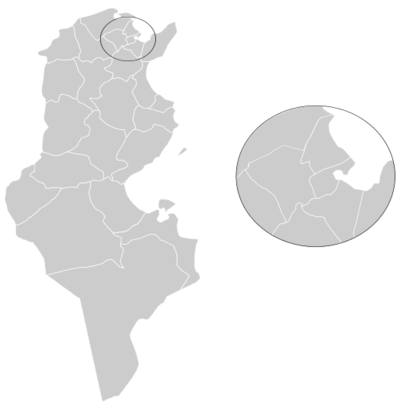

Administrative divisions

Tunisia is subdivided into 24 governorates (Wilaya), which are further divided into 264 "delegations" or "districts" (mutamadiyat), and further subdivided into municipalities (baladiyats)[122] and sectors (imadats).[123]

Economy

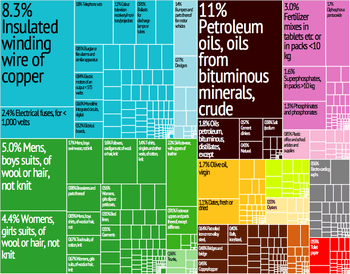

Tunisia is an export-oriented country in the process of liberalizing and privatizing an economy that, while averaging 5% GDP growth since the early 1990s, has suffered from corruption benefiting politically connected elites.[124] Tunisia's Penal Code criminalises several forms of corruption, including active and passive bribery, abuse of office, extortion and conflicts of interest, but the anti-corruption framework is not effectively enforced.[125] However, according to the Corruption Perceptions Index published annually by Transparency International, Tunisia was ranked the least corrupt North-African-country in 2016, with a score of 41. Tunisia has a diverse economy, ranging from agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and petroleum products, to tourism. In 2008 it had a GDP of US$41 billion (official exchange rates), or $82 billion (purchasing power parity).[8]

The agricultural sector accounts for 11.6% of the GDP, industry 25.7%, and services 62.8%. The industrial sector is mainly made up of clothing and footwear manufacturing, production of car parts, and electric machinery. Although Tunisia managed an average 5% growth over the last decade it continues to suffer from a high unemployment especially among youth.

Tunisia was in 2009 ranked the most competitive economy in Africa and the 40th in the world by the World Economic Forum.[126] Tunisia has managed to attract many international companies such as Airbus[127] and Hewlett-Packard.[128]

Tourism accounted for 7% of GDP and 370,000 jobs in 2009.[129]

The European Union remains Tunisia's first trading partner, currently accounting for 72.5% of Tunisian imports and 75% of Tunisian exports. Tunisia is one of the European Union's most established trading partners in the Mediterranean region and ranks as the EU's 30th largest trading partner. Tunisia was the first Mediterranean country to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union, in July 1995, although even before the date of entry came into force, Tunisia started dismantling tariffs on bilateral EU trade. Tunisia finalised the tariffs dismantling for industrial products in 2008 and therefore was the first non-EU Mediterranean country to enter in a free trade area with EU.[130]

Tunis Sports City is an entire sports city currently being constructed in Tunis, Tunisia. The city that will consist of apartment buildings as well as several sports facilities will be built by the Bukhatir Group at a cost of $5 Billion.[131] The Tunis Financial harbour will deliver North Africa's first offshore financial centre at Tunis Bay in a project with an end development value of US$3 billion.[132] The Tunis Telecom City is a US$3 billion project to create an IT hub in Tunis.[133]

Tunisia Economic City is a city being constructed near Tunis in Enfidha. The city will consist of residential, medical, financial, industrial, entertainment and touristic buildings as well as a port zone for a total cost of US$80 Billion. The project is financed by Tunisian and foreign enterprises.[134]

On 29 and 30 November 2016, Tunisia held an investment conference Tunisia2020 to attract $30 billion in investment projects.[135]

Days before Tunisia's 2019 parliamentary elections, the nation finds itself struggling with a sluggish economy. The Arab world's only democratic state fought hard against the dictatorial regime of president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali during the Arab Spring. Nevertheless, Tunisia could not accomplish anything more than freedom and democracy. It still finds itself hanging between inflation and unemployment while looking up to the 6 October elections with hope of a reform.[136]

Tourism

Among Tunisia's tourist attractions are its cosmopolitan capital city of Tunis, the ancient ruins of Carthage, the Muslim and Jewish quarters of Jerba, and coastal resorts outside of Monastir. According to The New York Times, Tunisia is "known for its golden beaches, sunny weather and affordable luxuries".[137]

Energy

Sources of electricity production in Tunisia[138]

The majority of the electricity used in Tunisia is produced locally, by state-owned company STEG (Société Tunisienne de l'Electricité et du Gaz). In 2008, a total of 13,747 GWh was produced in the country.[139]

Oil production of Tunisia is about 97,600 barrels per day (15,520 m3/d). The main field is El Bourma.[140]

Oil production began in 1966 in Tunisia. Currently there are 12 oil fields.[141]

Tunisia had plans for two nuclear power stations, to be operational by 2020. Both facilities are projected to produce 900–1000 MW. France is set to become an important partner in Tunisia's nuclear power plans, having signed an agreement, along with other partners, to deliver training and technology.[142][143] As of 2015, Tunisia has abandoned these plans. Instead, Tunisia is considering other options to diversify its energy mix, such as renewable energies, coal, shale gas, liquified natural gas and constructing a submarine power interconnection with Italy.[144]

According to the Tunisian Solar Plan (which is Tunisia's Renewable Energy Strategy not limited to solar, contrary to what its title may suggest, proposed by the National Agency for Energy Conservation), Tunisia's objective is to reach a share of 30% of renewable energies in the electricity mix by 2030, most of which should be accounted for by wind power and photovoltaics.[145] As of 2015, Tunisia had a total renewable capacity of 312 MW (245 MW wind, 62 MW hydropower, 15 MW photovoltaics.)[146][147]

Transport

The country maintains 19,232 kilometres (11,950 mi) of roads,[8] with three highways: the A1 from Tunis to Sfax (works ongoing for Sfax-Libya), A3 Tunis-Beja (works ongoing Beja – Boussalem, studies ongoing Boussalem – Algeria) and A4 Tunis – Bizerte. There are 29 airports in Tunisia, with Tunis Carthage International Airport and Djerba–Zarzis International Airport being the most important ones. A new airport, Enfidha – Hammamet International Airport opened in 2011. The airport is located north of Sousse at Enfidha and is to mainly serve the resorts of Hamammet and Port El Kantaoui, together with inland cities such as Kairouan. Five airlines are headquartered in Tunisia: Tunisair, Syphax airlines, Karthago Airlines, Nouvelair, and Tunisair Express. The railway network is operated by SNCFT and amounts to 2,135 kilometres (1,327 mi) in total.[8] The Tunis area is served by a Light rail network named Metro Leger which is managed by Transtu.

Water supply and sanitation

Tunisia has achieved the highest access rates to water supply and sanitation services in the Middle East and North Africa. As of 2011, access to safe drinking water became close to universal approaching 100% in urban areas and 90% in rural areas.[148] Tunisia provides good quality drinking water throughout the year.[149]

Responsibility for the water supply systems in urban areas and large rural centres is assigned to the Sociéte Nationale d'Exploitation et de Distribution des Eaux (SONEDE), a national water supply authority that is an autonomous public entity under the Ministry of Agriculture. Planning, design and supervision of small and medium water supplies in the remaining rural areas are the responsibility of the Direction Générale du Génie Rurale (DGGR).

In 1974, ONAS was established to manage the sanitation sector. Since 1993, ONAS has had the status of a main operator for protection of water environment and combating pollution.

The rate of non-revenue water is the lowest in the region at 21% in 2012.[150]

Demographics

According to the CIA, as of 2017, Tunisia has a population of 11,403,800 inhabitants.[8] The government has supported a successful family planning program that has reduced the population growth rate to just over 1% per annum, contributing to Tunisia's economic and social stability.[103]

Ethnic groups

According to CIA The World Factbook, ethnic groups in Tunisia are: Arab 98%, European 1%, Jewish and other 1%.[8]

According to the 1956 Tunisian census, Tunisia had a population at the time of 3,783,000 residents, of which mainly Berbers and Arabs. The proportion of speakers of Berber dialects was at 2% of the population.[151] According to another source the population of Arabs is estimated to be <40%[152] to 98%,[8][153][154] and that of Berbers at 1%[155] to over 60%.[152]

Amazighs are concentrated in the Dahar mountains and on the island of Djerba in the south-east and in the Khroumire mountainous region in the north-west. That said, an important number of genetic and other historical studies point out to the predominance of the Amazighs in Tunisia.[156]

An Ottoman influence has been particularly significant in forming the Turco-Tunisian community. Other peoples have also migrated to Tunisia during different periods of time, including West Africans, Greeks, Romans, Phoenicians (Punics), Jews, and French settlers.[157] By 1870 the distinction between the Arabic-speaking mass and the Turkish elite had blurred.[158]

From the late 19th century to after World War II, Tunisia was home to large populations of French and Italians (255,000 Europeans in 1956),[159] although nearly all of them, along with the Jewish population, left after Tunisia became independent. The history of the Jews in Tunisia goes back some 2,000 years. In 1948 the Jewish population was an estimated 105,000, but by 2013 only about 900 remained.[160]

The first people known to history in what is now Tunisia were the Berbers. Numerous civilizations and peoples have invaded, migrated to, or have been assimilated into the population over the millennia, with influences of population from Phoenicians/Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Spaniards, Ottoman Turks and Janissaries, and French. There was a continuing inflow of nomadic Arab tribes from Arabia.[48]

After the Reconquista and expulsion of non-Christians and Moriscos from Spain, many Spanish Muslims and Jews also arrived. According to Matthew Carr, "As many as eighty thousand Moriscos settled in Tunisia, most of them in and around the capital, Tunis, which still contains a quarter known as Zuqaq al-Andalus, or Andalusia Alley."[161]

Languages

Arabic is the official language, and Tunisian Arabic, known as Tounsi,[162] is the national, vernacular variety of Arabic and is used by the public.[163] There is also a small minority of speakers of Berber languages known collectively as Jebbali or Shelha.[164][165]

French also plays a major role in Tunisian society, despite having no official status. It is widely used in education (e.g., as the language of instruction in the sciences in secondary school), the press, and business. In 2010, there were 6,639,000 French-speakers in Tunisia, or about 64% of the population.[166] Italian is understood and spoken by a small part of the Tunisian population.[167] Shop signs, menus and road signs in Tunisia are generally written in both Arabic and French.[168]

Major cities

Religion

The majority of Tunisia's population (around 98%) are Muslims while about 2% follow Christianity and Judaism or other religions.[8] The bulk of Tunisians belong to the Maliki School of Sunni Islam and their mosques are easily recognizable by square minarets. However, the Turks brought with them the teaching of the Hanafi School during the Ottoman rule, which still survives among the Turkish descended families today, and their mosques traditionally have octagonal minarets.[170] Sunnis form the majority with non-denominational Muslims being the second largest group of Muslims,[171] followed by Ibadite Amazighs.[172][173]

Tunisia has a sizable Christian community of around over 35,000 adherents,[174][175] mainly Catholics (22,000) and to a lesser degree Protestants. Berber Christians continued to live in some Nefzaoua villages up until the early 15th century[176] and the community of Tunisian Christians existed in the town of Tozeur up to the 18th century.[54] International Religious Freedom Report for 2007 estimates thousands of Tunisian Muslims have converted to Christianity.[177][178] Judaism is the country's third largest religion with 900 members. One-third of the Jewish population lives in and around the capital. The remainder lives on the island of Djerba with 39 synagogues where the Jewish community dates back 2,600 years,[179] in Sfax, and in Hammam-Lif.[180]

Djerba, an island in the Gulf of Gabès, is home to El Ghriba synagogue, which is one of the oldest synagogues in the world and the oldest uninterruptedly used. Many Jews consider it a pilgrimage site, with celebrations taking place there once every year due to its age and the legend that the synagogue was built using stones from Solomon's temple.[181] In fact, Tunisia along with Morocco has been said to be the Arab countries most accepting of their Jewish populations.[182]

The constitution declares Islam as the official state religion and requires the President to be Muslim. Aside from the president, Tunisians enjoy a significant degree of religious freedom, a right enshrined and protected in its constitution, which guarantees the freedom of thoughts, beliefs and to practice one's religion.[180]

The country has a secular culture where religion is separated from not only political, but in public life. During the pre-revolution era there were at some point restrictions in the wearing of Islamic head scarves (hijab) in government offices and on public streets and public gatherings. The government believed the hijab is a "garment of foreign origin having a partisan connotation". There were reports that the Tunisian police harassed men with "Islamic" appearance (such as those with beards), detained them, and sometimes compelled men to shave their beards off.[183]

In 2006, the former Tunisian president declared that he would "fight" the hijab, which he refers to as "ethnic clothing".[184] Mosques were restricted from holding communal prayers or classes. After the revolution however, a moderate Islamist government was elected leading to more freedom in the practice of religion. It has also made room for the rise of fundamentalist groups such as the Salafists, who call for a strict interpretation of Sharia law.[185] The fall in favour of the moderate Islamist government of Ennahdha was partly due to that, modern Tunisian governments intelligence objectives are to suppress fundamentalist groups before they can act.

Individual Tunisians are tolerant of religious freedom and generally do not inquire about a person's personal beliefs.[180] Those who violate the rules of work and eating during the Islamic month of Ramadan may be arrested and jailed.[186]

In 2017 a handful of men were arrested for eating in public during Ramadan; they were convicted of committing "a provocative act of public indecency" and sentenced to month-long jail sentences. The state in Tunisia has a role as a "guardian of religion" which was used to justify the arrests.[187]

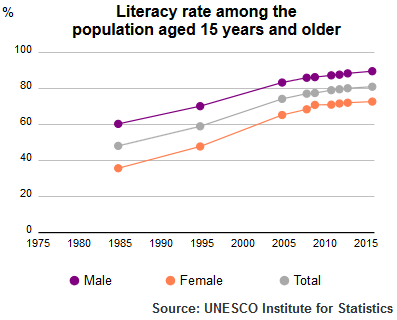

Education

The total adult literacy rate in 2008 was 78%[188] and this rate goes up to 97.3% when considering only people from 15 to 24 years old.[189] Education is given a high priority and accounts for 6% of GNP. A basic education for children between the ages of 6 and 16 has been compulsory since 1991. Tunisia ranked 17th in the category of "quality of the [higher] educational system" and 21st in the category of "quality of primary education" in The Global Competitiveness Report 2008–9, released by The World Economic Forum.[190]

While children generally acquire Tunisian Arabic at home, when they enter school at age 6, they are taught to read and write in Standard Arabic. From the age of 7, they are taught French while English is introduced at the age of 8.

The four years of secondary education are open to all holders of Diplôme de Fin d'Etudes de l'Enseignement de Base where the students focus on entering university level or join the workforce after completion. The Enseignement secondaire is divided into two stages: general academic and specialized. The higher education system in Tunisia has experienced a rapid expansion and the number of students has more than tripled over the past 10 years from approximately 102,000 in 1995 to 365,000 in 2005. The gross enrollment rate at the tertiary level in 2007 was 31 percent, with gender parity index of GER of 1.5.[190]

Health

In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 3.37% of the country's GDP. In 2009, there were 12.02 physicians and 33.12 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[191] The life expectancy at birth was 75.73 years in 2016, or 73.72 years for males and 77.78 years for females.[192] Infant mortality in 2016 was 11.7 per 1,000.[193]

Culture

The culture of Tunisia is mixed due to its long established history of outside influence from people ‒ such as Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Turks, Italians, Spaniards, and the French ‒ who all left their mark on the country.

Painting

The birth of Tunisian contemporary painting is strongly linked to the School of Tunis, established by a group of artists from Tunisia united by the desire to incorporate native themes and rejecting the influence of Orientalist colonial painting. It was founded in 1949 and brings together French and Tunisian Muslims, Christians and Jews. Pierre Boucherle was its main instigator, along with Yahia Turki, Abdelaziz Gorgi, Moses Levy, Ammar Farhat, and Jules Lellouche. Given its doctrine, some members have therefore turned to the sources of aesthetic Arab-Muslim art: such as miniature Islamic architecture, etc. Expressionist paintings by Amara Debbache, Jellal Ben Abdallah, and Ali Ben Salem are recognized while abstract art captures the imagination of painters like Edgar Naccache, Nello Levy, and Hedi Turki.[194]

After independence in 1956, the art movement in Tunisia was propelled by the dynamics of nation building and by artists serving the state. A Ministry of Culture was established, under the leadership of ministers such as Habib Boularès who oversaw art and education and power.[194] Artists gained international recognition such as Hatem El Mekki or Zoubeir Turki and influenced a generation of new young painters. Sadok Gmech draws his inspiration from national wealth while Moncef Ben Amor turns to fantasy. In another development, Youssef Rekik reused the technique of painting on glass and founded Nja Mahdaoui calligraphy with its mystical dimension.[194]

There are currently fifty art galleries housing exhibitions of Tunisian and international artists.[195] These galleries include Gallery Yahia in Tunis and Carthage Essaadi gallery.[195]

A new exposition opened in an old monarchal palace in Bardo dubbed the "awakening of a nation". The exposition boasts documents and artifacts from the Tunisian reformist monarchal rule in mid 19th century.[196]

Literature

Tunisian literature exists in two forms: Arabic and French. Arabic literature dates back to the 7th century with the arrival of Arab civilization in the region. It is more important in both volume and value than French literature, introduced during the French protectorate from 1881.[197]

Among the literary figures include Ali Douagi, who has produced more than 150 radio stories, over 500 poems and folk songs and nearly 15 plays,[198] Khraief Bashir, an Arabic novelist who published many notable books in the 1930s and which caused a scandal because the dialogues were written in Tunisian dialect,[198] and others such as Moncef Ghachem, Mohamed Salah Ben Mrad, or Mahmoud Messadi.

As for poetry, Tunisian poetry typically opts for nonconformity and innovation with poets such as Aboul-Qacem Echebbi.

As for literature in French, it is characterized by its critical approach. Contrary to the pessimism of Albert Memmi, who predicted that Tunisian literature was sentenced to die young,[199] a high number of Tunisian writers are abroad including Abdelwahab Meddeb, Bakri Tahar, Mustapha Tlili, Hele Beji, or Mellah Fawzi. The themes of wandering, exile and heartbreak are the focus of their creative writing.

The national bibliography lists 1249 non-school books published in 2002 in Tunisia, with 885 titles in Arabic.[200] In 2006 this figure had increased to 1,500 and 1,700 in 2007.[201] Nearly a third of the books are published for children.[202]

In 2014 Tunisian American creative nonfiction scribe and translator Med-Ali Mekki who wrote many books, not for publication but just for his own private reading translated the new Constitution of the Tunisian Republic from Arabic to English for the first time in Tunisian bibliographical history, the book was published worldwide the following year and it was the Internet's most viewed and downloaded Tunisian book.

Music

At the beginning of the 20th century, musical activity was dominated by the liturgical repertoire associated with different religious brotherhoods and secular repertoire which consisted of instrumental pieces and songs in different Andalusian forms and styles of origins, essentially borrowing characteristics of musical language. In 1930 "The Rachidia" was founded well known thanks to artists from the Jewish community. The founding in 1934 of a musical school helped revive Arab Andalusian music largely to a social and cultural revival led by the elite of the time who became aware of the risks of loss of the musical heritage and which they believed threatened the foundations of Tunisian national identity. The institution did not take long to assemble a group of musicians, poets, scholars. The creation of Radio Tunis in 1938 allowed musicians a greater opportunity to disseminate their works.

Notable Tunisian musicians include Saber Rebaï, Dhafer Youssef, Belgacem Bouguenna, Sonia M'barek, Latifa, Salah El Mahdi, Anouar Brahem, Emel Mathlouthi and Lotfi Bouchnak.

Media

The TV media has long remained under the domination of the Establishment of the Broadcasting Authority Tunisia (ERTT) and its predecessor, the Tunisian Radio and Television, founded in 1957. On 7 November 2006, President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali announced the demerger of the business, which became effective on 31 August 2007. Until then, ERTT managed all public television stations (Télévision Tunisienne 1 as well as Télévision Tunisienne 2 which had replaced the defunct RTT 2) and four national radio stations (Radio Tunis, Tunisia Radio Culture, Youth and Radio RTCI) and five regional Sfax, Monastir, Gafsa, Le Kef and Tataouine. Most programs are in Arabic but some are in French. Growth in private sector radio and television broadcasting has seen the creation of numerous operations including Radio Mosaique FM, Jawhara FM, Zaytuna FM, Hannibal TV, Ettounsiya TV, and Nessma TV.[203][204]

In 2007, some 245 newspapers and magazines (compared to only 91 in 1987) are 90% owned by private groups and independents.[205] The Tunisian political parties have the right to publish their own newspapers, but those of the opposition parties have very limited editions (like Al Mawkif or Mouwatinoun). Before the recent democratic transition, although freedom of the press was formally guaranteed by the constitution, almost all newspapers have in practice followed the government line report. Critical approach to the activities of the president, government and the Constitutional Democratic Rally Party (then in power) were suppressed. In essence, the media was dominated by state authorities through the Agence Tunis Afrique Presse. This has changed since, as the media censorship by the authorities have been largely abolished, and self-censorship has significantly decreased.[206] Nonetheless, the current regulatory framework and social and political culture mean that the future of press and media freedom is still unclear.[206]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Tunisia. The Tunisia national football team, also known as "The Eagles of Carthage," won the 2004 African Cup of Nations (ACN), which was held in Tunisia.[207][208] They also represented Africa in the 2005 FIFA Cup of Confederations, which was held in Germany, but they could not go beyond the first round.

The premier football league is the "Tunisian Ligue Professionnelle 1". The main clubs are Espérance Sportive de Tunis, Étoile Sportive du Sahel, Club Africain, Club Sportif Sfaxien, Union Sportive Monastirienne, and ES Metlaoui.

The Tunisia national handball team has participated in several handball world championships. In 2005, Tunisia came fourth. The national league consists of about 12 teams, with ES. Sahel and Esperance S.Tunis dominating. The most famous Tunisian handball player is Wissem Hmam. In the 2005 Handball Championship in Tunis, Wissem Hmam was ranked as the top scorer of the tournament. The Tunisian national handball team won the African Cup ten times, being the team dominating this competition. The Tunisians won the 2018 African Cup in Gabon by defeating Egypt.[209]

Tunisia's national basketball team has emerged as a top side in Africa. The team won the 2011 Afrobasket and hosted Africa's top basketball event in 1965, 1987 and 2015.

In boxing, Victor Perez ("Young") was world champion in the flyweight weight class in 1931 and 1932.[210]

In the 2008 Summer Olympics, Tunisian Oussama Mellouli won a gold medal in 1500 meter freestyle.[211] In the 2012 Summer Olympics, he won a bronze medal in the 1500 meter freestyle and a gold medal in the Men's marathon swim at a distance of 10 kilometers.

In 2012, Tunisia participated for the seventh time in her history in the Summer Paralympic Games. She finished the competition with 19 medals; 9 golds, 5 silvers and 5 bronzes. Tunisia was classified 14th on the Paralympics medal table and 5th in Athletics.

Tunisia was suspended from Davis Cup play for the year 2014, because the Tunisian Tennis Federation was found to have ordered Malek Jaziri not to compete against an Israeli tennis player, Amir Weintraub.[212] ITF president Francesco Ricci Bitti said: "There is no room for prejudice of any kind in sport or in society. The ITF Board decided to send a strong message to the Tunisian Tennis Federation that this kind of action will not be tolerated."[212]

References

- Notes

- References

- "Tunisia Constitution, Article 4" (PDF). 26 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "Tunisian Constitution, Article 1" (PDF). 26 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014. Translation by the University of Bern: "Tunisia is a free State, independent and sovereign; its religion is the Islam, its language is Arabic, and its form is the Republic."

- Arabic, Tunisian Spoken. Ethnologue (19 February 1999). Retrieved on 5 September 2015.

- "Tamazight language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Nawaat – Interview avec l' Association Tunisienne de Culture Amazighe". Nawaat.

- Gabsi, Z. (2003). An outline of the Shilha (Berber) vernacular of Douiret (Southern Tunisia). PhD Thesis, Western Sydney University.

- "Tunisian Amazigh and the Fight for Recognition – Tunisialive". Tunisialive. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011.

- "Tunisia". CIA World Factbook.

- "Tunisia" (PDF). International Religious Freedom Report for 2011, United States Department of State – Bureau of Democracy Human Rights and Labor.

- Frosini, Justin; Biagi, Francesco (2014). Political and Constitutional Transitions in North Africa: Actors and Factors. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-317-59745-2.

- Choudhry, Sujit; Stacey, Richard (2014) "Semi-presidential government in Tunisia and Egypt". International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "National Institute of Statistics-Tunisia". National Institute of Statistics-Tunisia. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Tunisia". International Monetary Fund.

- "GINI index". World Bank. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Human Development Report". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Report on the Delegation of تونس". Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- "Portal of the Presidency of the Government- Tunisia: government, administration, civil service, public services, regulations and legislation". Pm.gov.tn. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Tunisia | Country report | Freedom in the World | 2020". freedomhouse.org. 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Tethered by history". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Tunisie – France-Diplomatie – Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Développement international. Diplomatie.gouv.fr. Retrieved on 5 September 2015.

- (in French) Pourquoi l'Italie de Matteo Renzi se tourne vers la Tunisie avant l'Europe | JOL Journalism Online Press Archived 10 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Jolpress.com (28 February 2014). Retrieved on 5 September 2015.

- Ghanmi, Monia (12 September 2014) "La Tunisie renforce ses relations avec l'Italie". Magharebia

- "Tunisie : les législatives fixées au 26 octobre et la présidentielle au 23 novembre". Jeune Afrique. 25 June 2014.

- "Tunisia holds first post-revolution presidential poll". BBC News. 23 November 2014.

- "Freedom in the World 2018". Freedom House. 13 January 2018.

- "Democracy Index 2018". The Economist. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features, and Historic Sites. McFarland. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Rossi, Peter M.; White, Wayne Edward (1980). Articles on the Middle East, 1947–1971: A Cumulation of the Bibliographies from the Middle East Journal. Pierian Press, University of Michigan. p. 132.

- Taylor, Isaac (2008). Names and Their Histories: A Handbook of Historical Geography and Topographical Nomenclature. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-559-29668-0.

- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Brill. p. 838. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6.

- Livy, John Yardley & Hoyos, Dexter (2006). Hannibal's War: Books Twenty-one to Thirty. Oxford University Press. p. 705. ISBN 978-0-19-283159-0. and others associated with the word "تؤنس" (different from تونس) in Arabic which is a verb that means to socialize and to be friendly.

- Banjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Princeton University Press, 2013 p.147

- "Carthage and the Numidians". Hannibalbarca.webspace.virginmedia.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "Numidians (DBA II/40) and Moors (DBA II/57)". Fanaticus.org. 12 December 2001. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "Numidia (ancient region, Africa)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "The City of Carthage: From Dido to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Appian, The Punic Wars. livius.org

- "History of Tunisia – Lonely Planet Travel Information". lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "Donatist". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958) History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian, Part 2, Courier Corporation. pp.124–148

- Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002). Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. p. 264. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2.

- "Kairouan inscription as World Heritage". Kairouan.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Jonathan Conant (2012) Staying Roman, Conquest and Identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 358–378. ISBN 9781107530720

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- Ham, Anthony; Hole, Abigail; Willett, David. (2004). Tunisia (3 ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-74104-189-7.

- Stearns, Peter N.; Leonard Langer, William (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged (6 ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4.

- Houtsma, M. Th. (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. BRILL. p. 852. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000). International encyclopaedia of islamic dynasties. 4: A Continuing Series. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-81-261-0403-1.

- Ki-Zerbo, J.; Mokhtar, G.; Boahen, A. Adu; Hrbek, I. (1992). General history of Africa. James Currey Publishers. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-0-85255-093-9.

- Abulafia, "The Norman Kingdom of Africa", 27.

- "Populations Crises and Population Cycles, Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell". Galtoninstitute.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Hrbek, Ivan (1992). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. J. Currey. p. 34. ISBN 0852550936.

- Baadj, Amar (2013). "Saladin and the Ayyubid Campaigns in the Maghrib". Al-Qanṭara. 34 (2): 267–295. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2013.010.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7486-2137-8.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7486-2137-8.

- Panzac, Daniel (2005). Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800–1820. BRILL. p. 309. ISBN 978-90-04-12594-0.

- Clancy-Smith, Julia A. (1997). Rebel and Saint: Muslim Notables, Populist Protest, Colonial Encounters (Algeria and Tunisia, 1800–1904). University of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-520-92037-8.

- Gearon, Eamonn (2011). The Sahara: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-19-986195-8.

- Ion Smeaton Munro (1933). Through fascism to world power: a history of the revolution in Italy. A. Maclehose & co. p. 221.

- Williamson, Gordon (1991). Afrikakorps 1941–43. Osprey. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-85532-130-4.

- Palmer, Michael A. (2010). The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859–1945. Zenith Imprint. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7603-3780-6.

- "Tunisia profile". BBC News. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Tunisia Celebrates Independence Day". AllAfrica.com. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Habib Bourguiba: Father of Tunisia". BBC. 6 April 2000.

- Black, Ian (13 July 2010). "Amnesty International censures Tunisia over human right". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "BBC News | OBITUARIES | Habib Bourguiba: Father of Tunisia". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- AP (7 November 1987). "A Coup Is Reported in Tunisia". NYtimes.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Vely, Yannick (23 November 2009). "Ben Ali, sans discussion". ParisMatch.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Ganley, Elaine; Barchfield, Jenny (17 January 2011). "Tunisians hail fall of ex-leader's corrupt family". Sandiegounion-tribune.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2013). "The Other Side of a Neoliberal Miracle: Economic Reform and Political De-Liberalization in Ben Ali's Tunisia". Mediterranean Politics. 18 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1080/13629395.2012.761475. S2CID 154822868.

- "Tunisie: comment s'enrichit le clan Ben Ali?" (in French). RadicalParty.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Caught in the Net: Tunisia's First Lady". Foreign Policy. 13 December 2007.

- "Ajaccio – Un trafic de yachts entre la France et la Tunisie en procès" (in French). 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Florence Beaugé (24 October 2009). "Le parcours fulgurant de Sakhr El-Materi, gendre du président tunisien Ben Ali". LeMonde.fr. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Tunisia". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Protectionline.org". Protectionline.org. 18 January 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Droits de l'Homme : après le harcèlement, l'asphyxie". RFI.fr. 16 December 2004. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Dans le monde de l'après-11 septembre, seule la paix protège les libertés". RSF.org. 22 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Yasmine Ryan (26 January 2011). "How Tunisia's revolution began – Features". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "Wikileaks might have triggered Tunis' revolution". Alarabiya. 15 January 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Spencer, Richard (13 January 2011). "Tunisia riots: Reform or be overthrown, US tells Arab states amid fresh riots". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Ryan, Yasmine (14 January 2011). "Tunisia's bitter cyberwar". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- "Trade unions: the revolutionary social network at play in Egypt and Tunisia". Defenddemocracy.org. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Charles., Tripp (2013). The power and the people : paths of resistance in the Middle East. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521809658. OCLC 780063882.

- "When fleeing Tunisia, don't forget the gold". Korea Times. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Interim President Announces Election of National Constituent Assembly on July 24". Tunis Afrique Presse. 3 March 2011 – via ProQuest.

- "Tunisian PM Announces October Date for Elections". BBC Monitoring Middle East. 9 June 2011 – via ProQuest.

- El Amrani, Issandr; Lindsey, Ursula (8 November 2011). "Tunisia Moves to the Next Stage". Middle East Report. Middle East Research and Information Project. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Zavis, Alexandra (13 December 2011). "Former dissident sworn in as Tunisia's president". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Tunisia's constitution will not be based on Sharia: Islamist party". Al Arabiya. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- Fleishman, Jeffrey (6 February 2013). "Tunisian opposition leader Chokri Belaid shot dead outside his home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "Tunisia launches Truth and Dignity Commission". UNDP. 9 June 2014.

- "The real reason Tunisia renewed its state of emergency". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 2015". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- Ewan W., Anderson (2003). International Boundaries: Geopolitical Atlas. Psychology Press. p. 816. ISBN 978-1-57958-375-0.

- "Climate of Tunisia". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Aldosari, Ali (2006). Middle East, western Asia, and northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 1270–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- "Weatherbase : Tunisia". Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Tunisia holds first election under new constitution". BBC News. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "EIU Democracy Index 2016". infographics.economist.com.

- "Tunisia (03/09/12)". US Department of State. 9 March 2012.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. "TUNISIA. Majlis Al-Nuwab (Chamber of Deputies)". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "49 femmes élues à l'assemblée constituante : 24% des 217 sièges". Leaders. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Ben Hamadi, Monia (29 April 2014). "Tunisie: Selma Znaidi, une femme de plus à l'Assemblée". Al Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Tunisia holds first post-revolution presidential poll". BBC News. 23 November 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- "Tunisia" (PDF). Reunite International. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "State Department page on Tunisia". State.gov. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Major Trends Affecting Families: A Background Document. United Nations Publications. 2003. p. 190. ISBN 978-92-1-130252-3. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Tamanna, Nowrin (December 2008). "Personal status laws in Morocco and Tunisia: a comparative exploration of the possibilities for equality-enhancing reform in Bangladesh". Feminist Legal Studies. 16 (3): 323–343. doi:10.1007/s10691-008-9099-9. S2CID 144717130.

- "Scores arrested after Tunis art riots". AlJazeera. 12 June 2012.

- "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016.

- "Two Men Sentenced To 8 Months in Jail For Suspicion of Being Gay". Instinct Magazine. 14 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "The Global Divide on Homosexuality." pewglobal. 4 June 2013

- "The Tunisian women locked up for smoking a joint". BBC. 18 March 2016.

- "It will no longer be legal to rape a woman in Tunisia if you marry her afterwards". The Independent. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Radio, Sveriges. "Våld mot kvinnor blir olagligt i Tunisien – Nyheter (Ekot)". Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Nyheter, SVT. "Våldtäktslagen tas bort i Tunisien". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 2008). The Military Balance 2008. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-85743-461-3.

- "Tunisia – Armed forces". Nationsencyclopedia.com. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- "Tunisia Governorates". Statoids.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Portail de l'industrie Tunisienne" (in French). Tunisieindustrie.nat.tn. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "GTZ in Tunisia". gtz.de. GTZ. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- "Tunisia Corruption Profile". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "The Global Competitiveness Index 2009–2010 rankings" (PDF). weforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Airbus build plant in tunisia". Eturbonews. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "HP to open customer service center in Tunisia". africanmanager.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Trouble in paradise: How one vendor unmasked the 'economic miracle'". Mobile.france24.com. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "Bilateral relations Tunisia EU". europa.eu. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Tunis Sport City". Sportcitiesinternational.com. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Tunis Financial Harbour". Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Vision 3 announces Tunis Telecom City". ameinfo.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Welcome at TEC – Tunisia Economic City. Tunisiaec.com (4 April 2015). Retrieved on 5 September 2015.

- "Tunisia2020 attracts billions in foreign funds". Tunisia live. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- "Democracy hangs in the balance in Tunisia". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Glusac, Elaine (22 November 2009). "A Night, and Day, In Tunisia at a New Resort". The New York Times.

- Arfa, M. Othman Ben. "Effort national de maitrise de l'energie : contribution de la steg" (PDF). steg.com.tn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- "STEG, company website". steg.com.tn. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- "Oil and Gas in Tunisia". mbendi.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- "MBendi oilfields in Tunisia". mbendi.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- "Tunisias nuclear plans". Reuters. 23 April 2009.

- "Tunisia : A civil nuclear station of 1000 Megawatt and two sites are selected". africanmanager.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nouvelle version du plan solaire tunisien. anme.nat.tn (April 2012)

- "Tunisia Energy Situation".

- Production de l’électricité en Tunisie. oitsfax.org

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. "Joint Monitoring Programme for Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation". Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- (in French) Ministere du Developpement et de la Cooperation Internationale, Banque Mondiale et Programme "Participation Privee dans les infrastructures mediterreeanees"(PPMI):Etude sur la participation privée dans les infrastructures en Tunisie Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Volume III, 2004, accessed on 21 March 2010

- "Chiffres clés". SONEDE. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Owen's Commerce & Travel and International Register. Owen's Commerce & Travel Limited. 1964. p. 273. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Tej K. Bhatia, William C. Ritchie (2006). The Handbook of Bilingualism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 860. ISBN 978-0631227359. Retrieved 15 August 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Turchi, C; Buscemi, L; Giacchino, E; Onofri, V; Fendt, L; Parson, W; Tagliabracci, A (2009). "Polymorphisms of mtDNA control region in Tunisian and Moroccan populations: An enrichment of forensic mtDNA databases with Northern Africa data". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 3 (3): 166–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.01.014. PMID 19414164.

- Bouhadiba, M.A. (28 January 2010). "Le Tunisien: une dimension méditerranéenne qu'atteste la génétique" (in French). Lapresse.tn. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Q&A: The Berbers". BBC News. 12 March 2004. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Indigenous Peoples in Tunisia". www.iwgia.org. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Tunisia – Land | history – geography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- Green, Arnold H. (1978), The Tunisian Ulama 1873–1915: Social Structure and Response to Ideological Currents, Brill, p. 69, ISBN 978-90-04-05687-9

- Angus Maddison (2007). Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History: Essays in Macro-Economic History. OUP Oxford. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "The Jews of Tunisia". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- Carr, Matthew (2009). Blood and faith: the purging of Muslim Spain. The New Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-59558-361-1.

- Sayahi, Lotfi (2014). Diglossia and Language Contact: Language Variation and Change in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-139-86707-8.