Saponin

Saponins are a class of chemical compounds found in particular abundance in various plant species. More specifically, they are amphipathic glycosides grouped phenomenologically by the soap-like foam they produce when shaken in aqueous solutions, and structurally by having one or more hydrophilic glycone moieties combined with a lipophilic triterpene or steroid derivative.[1][2]

Structural variety and biosynthesis

The aglycone (glycoside-free) portions of the saponins are termed sapogenins. The number of saccharide chains attached to the sapogenin/aglycone core can vary – giving rise to another dimension of nomenclature (monodesmosidic, bidesmosidic, etc.[1]) – as can the length of each chain. A somewhat dated compilation has the range of saccharide chain lengths being 1–11, with the numbers 2–5 being the most frequent, and with both linear and branched chain saccharides being represented.[1] Dietary monosaccharides such as D-glucose and D-galactose are among the most common components of the attached chains.[1]

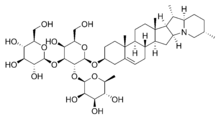

The lipophilic aglycone can be any one of a wide variety of polycyclic organic structures originating from the serial addition of 10-carbon (C10) terpene units to compose a C30 triterpene skeleton,[3][4] often with subsequent alteration to produce a C27 steroidal skeleton.[1] The subset of saponins that are steroidal have been termed saraponins.[2] Aglycone derivatives can also incorporate nitrogen, so some saponins also present chemical and pharmacologic characteristics of alkaloid natural products. The figure at right above presents the structure of the alkaloid phytotoxin solanine, a monodesmosidic, branched-saccharide steroidal saponin. (The lipophilic steroidal structure is the series of connected six- and five-membered rings at the right of the structure, while the three oxygen-rich sugar rings are at left and below. Note the nitrogen atom inserted into the steroid skeleton at right.)

Sources

Saponins have historically been understood to be plant-derived, but they have also been isolated from marine organisms such as sea cucumber.[1][5] Saponins are indeed found in many plants,[1][6] and derive their name from the soapwort plant (genus Saponaria, family Caryophyllaceae), the root of which was used historically as a soap.[2] Saponins are also found in the botanical family Sapindaceae, including its defining genus Sapindus (soapberry or soapnut) and the horse chestnut, and in the closely related families Aceraceae (maples) and Hippocastanaceae). It is also found heavily in Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Gynostemma, Cucurbitaceae) in a form called gypenosides, and ginseng or red ginseng (Panax, Araliaceae) in a form called ginsenosides. Saponins are also found in the unripe fruit of Manilkara zapota (also known as sapodillas), resulting in highly astringent properties. Within these families, this class of chemical compounds is found in various parts of the plant: leaves, stems, roots, bulbs, blossom and fruit.[7] Commercial formulations of plant-derived saponins, e.g., from the soap bark (or soapbark) tree, Quillaja saponaria, and those from other sources are available via controlled manufacturing processes, which make them of use as chemical and biomedical reagents.[8] In China, the rhizomes (tubers) of Dioscorea zingiberensis C.H. Wright also produces steroidal saponins (TSS) as part of a treatment for cardiovascular disease.[9]

Test

- Froth Test

Uses plant Gogo (bark) Entada phaseoloides as control. The positive result shows a honeycomb froth that is higher than 2 cm that persists for 10 minutes or longer.

Blood Agar Media (BAM): Is an agar cup semi-quantitative method that shows positive result of hemolytic halos.[10]

Role in plant ecology and impact on animal foraging

In plants, saponins may serve as anti-feedants,[2][4] and to protect the plant against microbes and fungi. Some plant saponins (e.g. from oat and spinach) may enhance nutrient absorption and aid in animal digestion. However, saponins are often bitter to taste, and so can reduce plant palatability (e.g., in livestock feeds), or even imbue them with life-threatening animal toxicity.[4] Some saponins are toxic to cold-blooded organisms and insects at particular concentrations.[4] Further research is needed to define the roles of these natural products in their host organisms, which have been described as "poorly understood" to date.[4]

Ethnobotany

Most saponins, which readily dissolve in water, are poisonous to fish.[11] Therefore, in ethnobotany, they are primarily known for their use by indigenous people in obtaining aquatic food sources. Since prehistoric times, cultures throughout the world have used fish-killing plants, mostly those containing saponins, for fishing.[12][13]

Although prohibited by law, fish-poison plants are still widely used by indigenous tribes in Guyana.[14]

On the Indian subcontinent, the Gondi people are known for their use of poison-plant extracts in fishing.[15]

Many of California's Native American tribes traditionally used soaproot, (genus Chlorogalum) and/or the root of various yucca species, which contain saponin, as a fish poison. They would pulverize the roots, mixing in water to create a foam, and then add the suds to a stream. This would kill, or incapacitate, the fish, which could be gathered easily from the surface of the water. Among the tribes using this technique were the Lassik, the Luiseño, and the Mattole.[16]

Research and uses

The amphipathic nature of saponins gives them activity as surfactants with potential ability to interact with cell membrane components, such as cholesterol and phospholipids, possibly making saponins useful for development of cosmetics and drugs.[17] Saponins have also been used as adjuvants in development of vaccines,[18] such as Quil A, an extract from the bark of Quillaja saponaria.[17][19] This makes them of interest for possible use in subunit vaccines and vaccines directed against intracellular pathogens.[18] In their use as adjuvants for manufacturing vaccines, toxicity associated with sterol complexation remains a concern.[20]

While saponins are promoted commercially as dietary supplements and are used in traditional medicine, there is no high-quality clinical evidence that they have any beneficial effect on human health.[19] Quillaja is toxic when consumed in large amounts, involving possible liver damage, gastric pain, diarrhea, or other adverse effects.[19]

The plant Çöven, Gypsophila simonii is widely distributed throughout Çankırı, where it is a native species, and Turkey. In this study, chemical and physical properties of unripe saponins obtained by extraction from the roots of Gypsophila simonii, an endemic plant, were isolated and investigated. Purified aglycones recovered from acid hydrolysis of the saponins were separated by reversed chromatography on a thin layer of silica gel. Phytochemical tests showed the presence of terpenoids in the crude extracts.[21][22]

Saponins are used for their effects on ammonia emissions in animal feeding.[23] In the United States, researchers are exploring the use of saponins derived from plants to control invasive worm species, including the jumping worm.[24][25]

Dioscin, the saponin from Dioscorea spp. remains an important source for diosgenin, which is then utilized in the semi-synthetic or biosynthetic production of progesterone and corticosteroids.

There

See also

- Phytochemical

- Triterpenoid saponins

References

- Hostettmann, K.; A. Marston (1995). Saponins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 3ff. ISBN 978-0-521-32970-5. OCLC 29670810.

- "Saponins". Cornell University. 14 August 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- "Project Summary: Functional Genomics of Triterpene Saponin Biosynthesis in Medicago Truncatula". Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- Foerster, Hartmut (22 May 2006). "MetaCyc Pathway: saponin biosynthesis I". Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- Riguera, Ricardo (August 1997). "Isolating bioactive compounds from marine organisms". Journal of Marine Biotechnology. 5 (4): 187–193.

- Liener, Irvin E (1980). Toxic constituents of plant foodstuffs. New York City: Academic Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-12-449960-7. OCLC 5447168.

- http://sun.ars-grin.gov:8080/npgspub/xsql/duke/plantdisp.xsql?taxon=691

- "Saponin from quillaja bark". Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- Li, H.; Huang, W.; Wen, Y.; Gong, G.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, G. (December 2010). "Anti-thrombotic activity and chemical characterization of steroidal saponins from Dioscorea zingiberensis C.H. Wright". Fitoterapia. 81 (8): 1147–56. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2010.07.016. PMID 20659537.

- Antibacterial activity of leave extracts of Nymphaea lotus (Nymphaeaceae) on Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) isolated from clinical samples. Akinjogunla OJ, Yah CS, Eghafona NO and Ogbemudia FO, Annals of Biological Research, 2010, 1 (2), pages 174–184

- Howes, F. N. (1930), "Fish-poison plants", Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew), 1930 (4): 129–153, doi:10.2307/4107559, JSTOR 4107559

- Jonathan G. Cannon, Robert A. Burton, Steven G. Wood, and Noel L. Owen (2004), "Naturally Occurring Fish Poisons from Plants", J. Chem. Educ., 81 (10): 1457, Bibcode:2004JChEd..81.1457C, doi:10.1021/ed081p1457CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- C. E. Bradley (1956), "Arrow and fish poison of the American southwest", Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, 10 (4), pp. 362–366, doi:10.1007/BF02859766

- Tinde Van Andel (2000), "The diverse uses of fish-poison plants in Northwest Guyana", Economic Botany, 54 (4): 500–512, doi:10.1007/BF02866548

- Murthy E N, Pattanaik, Chiranjibi, Reddy, C Sudhakar, Raju, V S (March 2010), "Piscicidal plants used by Gond tribe of Kawal wildlife sanctuary, Andhra Pradesh, India", Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources, 1 (1): 97–101CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Campbell, Paul (1999). Survival skills of native California. Gibbs Smith. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-87905-921-7.

- Lorent, Joseph H.; Quetin-Leclercq, Joëlle; Mingeot-Leclercq, Marie-Paule (28 November 2014). "The amphiphilic nature of saponins and their effects on artificial and biological membranes and potential consequences for red blood and cancer cells". Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. 12 (44): 8803–8822. doi:10.1039/c4ob01652a. ISSN 1477-0520. PMID 25295776.

- Sun, Hong-Xiang; Xie, Yong; Ye, Yi-Ping (2009). "Advances in saponin-based adjuvants". Vaccine. 27 (12): 1787–1796. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.091. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 19208455.

- "Quillaja". Drugs.com. 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Skene, Caroline D.; Philip Sutton (1 September 2006). "Saponin-adjuvanted particulate vaccines for clinical use". Methods. 40 (1): 53–9. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.019. PMID 16997713.

- Yücekutlu, A. Nihal (2000). Çöven (Gypsophila simonii Hub. Mor) Kökünden Saponin Saflaştırılması, Gazi Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Kimya, Yüksek Lisans Tezi. 64s. Ankara.

- Yücekutlu, A. Nihal and Bildacı, Işık (2008). "Determination of Plant Saponins and Some of Gypsophila Species. A Review of the Literature". Hacettepe Journal of Biology and Chemistry, 36(2), 129-135.

- Zentner, Eduard (July 2011). "Effects of phytogenic feed additives containing quillaja saponaria on ammonia in fattening pigs" (PDF). Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Roach, Margaret (22 July 2020). "As Summer Takes Hold, So Do the Jumping Worms". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Invasive 'Jumping' Worms Are Now Tearing Through Midwestern Forests". Audubon. 2 January 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saponins. |