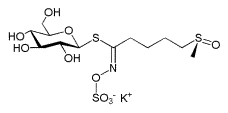

Glucoraphanin

Glucoraphanin is a glucosinolate found in broccoli,[1] cauliflower,[2] and mustard.[3]

Potassium salt of glucoraphanin | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-S-[(1E)-5-(methylsulfinyl)-N-(sulfonatooxy)pentanimidoyl]-1-thio-β-D-glucopyranose | |

| Other names

Glucorafanin; 4-Methylsulfinylbutyl glucosinolate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H23NO10S3 | |

| Molar mass | 437.49 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Glucoraphanin is converted to sulforaphane by the enzyme myrosinase[4]. In plants, sulforaphane deters insect predators and acts as a selective antibiotic.[5] In humans, sulforaphane has been studied for its potential effects in neurodegenerative[6] and cardiovascular diseases.[7]

Due to the potential health benefits, a variety of broccoli has been bred to contain two to three times more glucoraphanin than standard broccoli.[8]

Romanesco broccoli has been found to contain ten times more glucoraphanin than typical broccoli varieties.[9] Frostara, Black Tuscany and red cabbage also contain much higher levels of glucoraphanin than broccoli.[9]

References

- James, D.; Devaraj, S.; Bellur, P.; Lakkanna, S.; Vicini, J.; Boddupalli, S. (2012). "Novel concepts of broccoli sulforaphanes and disease: Induction of phase II antioxidant and detoxification enzymes by enhanced-glucoraphanin broccoli". Nutrition Reviews. 70 (11): 654–65. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00532.x. PMID 23110644.

- Jeffery, E. H.; Brown, A. F.; Kurilich, A. C.; Keck, A. S.; Matusheski, N.; Klein, B. P.; Juvik, J. A. (2003). "Variation in content of bioactive components in broccoli". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 16 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00045-0.

- Oh, K.; SangOk, K.; Rak, C. (2015). "Sinigrin content of different parts of Dolsan leaf mustard". Korean Journal of Food Preservation. 22 (4): 553–558. doi:10.11002/kjfp.2015.22.4.553.

- Cuomo, Valentina; Luciano, Fernando B.; Meca, Giuseppe; Ritieni, Alberto; Mañes, Jordi (26 November 2014). "Bioaccessibility of glucoraphanin from broccoli using an gastrointestinal digestion model". CyTA - Journal of Food. 13 (3): 361–365. doi:10.1080/19476337.2014.984337.

- Fahey, Jed W.; Holtzclaw, W. David; Wehage, Scott L.; Wade, Kristina L.; Stephenson, Katherine K.; Talalay, Paul; Mukhopadhyay, Partha (2 November 2015). "Sulforaphane Bioavailability from Glucoraphanin-Rich Broccoli: Control by Active Endogenous Myrosinase". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0140963. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140963. PMC 4629881. PMID 26524341.

- Tarozzi, Andrea; Angeloni, Cristina; Malaguti, Marco; Morroni, Fabiana; Hrelia, Silvana; Hrelia, Patrizia (2013). "Sulforaphane as a Potential Protective Phytochemical against Neurodegenerative Diseases". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2013/415078. PMC 3745957. PMID 23983898.

- Bai, Yang; Wang, Xiaolu; Zhao, Song; Ma, Chunye; Cui, Jiuwei; Zheng, Yang (2015). "Sulforaphane Protects against Cardiovascular Disease via Nrf2 Activation". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2015: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2015/407580. PMC 4637098. PMID 26583056.

- Cheng, Maria (October 26, 2011). "UK scientists grow super broccoli". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Hahn, Christoph; Müller, Anja; Kuhnert, Nikolai; Albach, Dirk (2016-04-27). "Diversity of Kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica): Glucosinolate Content and Phylogenetic Relationships". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 64 (16): 3215–3225. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01000. ISSN 0021-8561.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.