Frequency

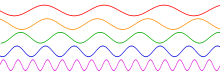

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time.[1] It is also referred to as temporal frequency, which emphasizes the contrast to spatial frequency and angular frequency. Frequency is measured in units of hertz (Hz) which is equal to one occurrence of a repeating event per second. The period is the duration of time of one cycle in a repeating event, so the period is the reciprocal of the frequency.[2] For example: if a newborn baby's heart beats at a frequency of 120 times a minute (2 hertz), its period, T, — the time interval between beats—is half a second (60 seconds divided by 120 beats). Frequency is an important parameter used in science and engineering to specify the rate of oscillatory and vibratory phenomena, such as mechanical vibrations, audio signals (sound), radio waves, and light.

| Frequency | |

|---|---|

Common symbols | f, ν |

| SI unit | Hz |

| In SI base units | s−1 |

| Dimension | |

Definitions

For cyclical processes, such as rotation, oscillations, or waves, frequency is defined as a number of cycles per unit time. In physics and engineering disciplines, such as optics, acoustics, and radio, frequency is usually denoted by a Latin letter f or by the Greek letter or ν (nu) (see e.g. Planck's formula).

The relation between the frequency and the period, , of a repeating event or oscillation is given by

Units

The SI derived unit of frequency is the hertz (Hz), named after the German physicist Heinrich Hertz. One hertz means that an event repeats once per second. If a TV has a refresh rate of 1 hertz the TV's screen will change (or refresh) its picture once per second. A previous name for this unit was cycles per second (cps). The SI unit for period is the second.

A traditional unit of measure used with rotating mechanical devices is revolutions per minute, abbreviated r/min or rpm. 60 rpm equals one hertz.[3]

Period versus frequency

As a matter of convenience, longer and slower waves, such as ocean surface waves, tend to be described by wave period rather than frequency. Short and fast waves, like audio and radio, are usually described by their frequency instead of period. These commonly used conversions are listed below:

| Frequency | 1 mHz (10−3 Hz) | 1 Hz (100 Hz) | 1 kHz (103 Hz) | 1 MHz (106 Hz) | 1 GHz (109 Hz) | 1 THz (1012 Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1 ks (103 s) | 1 s (100 s) | 1 ms (10−3 s) | 1 µs (10−6 s) | 1 ns (10−9 s) | 1 ps (10−12 s) |

Related types of frequency

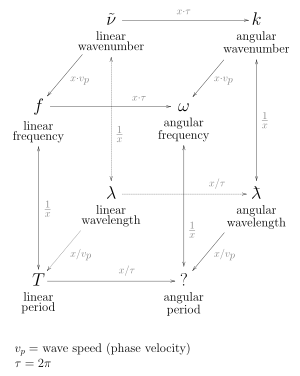

- Angular frequency, usually denoted by the Greek letter ω (omega), is defined as the rate of change of angular displacement, θ, (during rotation), or the rate of change of the phase of a sinusoidal waveform (notably in oscillations and waves), or as the rate of change of the argument to the sine function:

- Angular frequency is commonly measured in radians per second (rad/s) but, for discrete-time signals, can also be expressed as radians per sampling interval, which is a dimensionless quantity. Angular frequency (in radians) is larger than regular frequency (in Hz) by a factor of 2π.

- Spatial frequency is analogous to temporal frequency, but the time axis is replaced by one or more spatial displacement axes. E.g.:

- Wavenumber, k, is the spatial frequency analogue of angular temporal frequency and is measured in radians per meter. In the case of more than one spatial dimension, wavenumber is a vector quantity.

In wave propagation

For periodic waves in nondispersive media (that is, media in which the wave speed is independent of frequency), frequency has an inverse relationship to the wavelength, λ (lambda). Even in dispersive media, the frequency f of a sinusoidal wave is equal to the phase velocity v of the wave divided by the wavelength λ of the wave:

In the special case of electromagnetic waves moving through a vacuum, then v = c, where c is the speed of light in a vacuum, and this expression becomes:

When waves from a monochrome source travel from one medium to another, their frequency remains the same—only their wavelength and speed change.

Measurement

Measurement of frequency can be done in the following ways,

Counting

Calculating the frequency of a repeating event is accomplished by counting the number of times that event occurs within a specific time period, then dividing the count by the length of the time period. For example, if 71 events occur within 15 seconds the frequency is:

If the number of counts is not very large, it is more accurate to measure the time interval for a predetermined number of occurrences, rather than the number of occurrences within a specified time.[4] The latter method introduces a random error into the count of between zero and one count, so on average half a count. This is called gating error and causes an average error in the calculated frequency of , or a fractional error of where is the timing interval and is the measured frequency. This error decreases with frequency, so it is generally a problem at low frequencies where the number of counts N is small.

Stroboscope

An older method of measuring the frequency of rotating or vibrating objects is to use a stroboscope. This is an intense repetitively flashing light (strobe light) whose frequency can be adjusted with a calibrated timing circuit. The strobe light is pointed at the rotating object and the frequency adjusted up and down. When the frequency of the strobe equals the frequency of the rotating or vibrating object, the object completes one cycle of oscillation and returns to its original position between the flashes of light, so when illuminated by the strobe the object appears stationary. Then the frequency can be read from the calibrated readout on the stroboscope. A downside of this method is that an object rotating at an integral multiple of the strobing frequency will also appear stationary.

Frequency counter

Higher frequencies are usually measured with a frequency counter. This is an electronic instrument which measures the frequency of an applied repetitive electronic signal and displays the result in hertz on a digital display. It uses digital logic to count the number of cycles during a time interval established by a precision quartz time base. Cyclic processes that are not electrical in nature, such as the rotation rate of a shaft, mechanical vibrations, or sound waves, can be converted to a repetitive electronic signal by transducers and the signal applied to a frequency counter. As of 2018, frequency counters can cover the range up to about 100 GHz. This represents the limit of direct counting methods; frequencies above this must be measured by indirect methods.

Heterodyne methods

Above the range of frequency counters, frequencies of electromagnetic signals are often measured indirectly by means of heterodyning (frequency conversion). A reference signal of a known frequency near the unknown frequency is mixed with the unknown frequency in a nonlinear mixing device such as a diode. This creates a heterodyne or "beat" signal at the difference between the two frequencies. If the two signals are close together in frequency the heterodyne is low enough to be measured by a frequency counter. This process only measures the difference between the unknown frequency and the reference frequency. To reach higher frequencies, several stages of heterodyning can be used. Current research is extending this method to infrared and light frequencies (optical heterodyne detection).

Examples

Light

Visible light is an electromagnetic wave, consisting of oscillating electric and magnetic fields traveling through space. The frequency of the wave determines its color: 4×1014 Hz is red light, 8×1014 Hz is violet light, and between these (in the range 4-8×1014 Hz) are all the other colors of the visible spectrum. An electromagnetic wave can have a frequency less than 4×1014 Hz, but it will be invisible to the human eye; such waves are called infrared (IR) radiation. At even lower frequency, the wave is called a microwave, and at still lower frequencies it is called a radio wave. Likewise, an electromagnetic wave can have a frequency higher than 8×1014 Hz, but it will be invisible to the human eye; such waves are called ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Even higher-frequency waves are called X-rays, and higher still are gamma rays.

All of these waves, from the lowest-frequency radio waves to the highest-frequency gamma rays, are fundamentally the same, and they are all called electromagnetic radiation. They all travel through a vacuum at the same speed (the speed of light), giving them wavelengths inversely proportional to their frequencies.

where c is the speed of light (c in a vacuum, or less in other media), f is the frequency and λ is the wavelength.

In dispersive media, such as glass, the speed depends somewhat on frequency, so the wavelength is not quite inversely proportional to frequency.

Sound

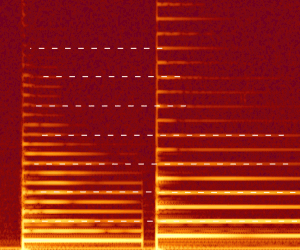

Sound propagates as mechanical vibration waves of pressure and displacement, in air or other substances.[5]. In general, frequency components of a sound determine its "color", its timbre. When speaking about the frequency (in singular) of a sound, it means the property that most determines pitch.[6]

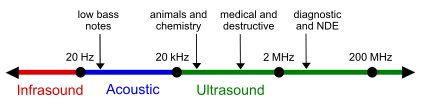

The frequencies an ear can hear are limited to a specific range of frequencies. The audible frequency range for humans is typically given as being between about 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (20 kHz), though the high frequency limit usually reduces with age. Other species have different hearing ranges. For example, some dog breeds can perceive vibrations up to 60,000 Hz.[7]

In many media, such as air, the speed of sound is approximately independent of frequency, so the wavelength of the sound waves (distance between repetitions) is approximately inversely proportional to frequency.

Line current

In Europe, Africa, Australia, Southern South America, most of Asia, and Russia, the frequency of the alternating current in household electrical outlets is 50 Hz (close to the tone G), whereas in North America and Northern South America, the frequency of the alternating current in household electrical outlets is 60 Hz (between the tones B♭ and B; that is, a minor third above the European frequency). The frequency of the 'hum' in an audio recording can show where the recording was made, in countries using a European, or an American, grid frequency.

See also

- Aperiodic frequency

- Audio frequency

- Bandwidth (signal processing)

- Cutoff frequency

- Downsampling

- Electronic filter

- Frequency band

- Frequency converter

- Frequency domain

- Frequency distribution

- Frequency extender

- Frequency grid

- Frequency modulation

- Frequency spectrum

- Interaction frequency

- Natural frequency

- Negative frequency

- Periodicity (disambiguation)

- Pink noise

- Preselector

- Radar signal characteristics

- Signaling (telecommunications)

- Spread spectrum

- Spectral component

- Transverter

- Upsampling

References

- "Definition of FREQUENCY". Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- "Definition of PERIOD". Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Davies, A. (1997). Handbook of Condition Monitoring: Techniques and Methodology. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-61320-3.

- Bakshi, K.A.; A.V. Bakshi; U.A. Bakshi (2008). Electronic Measurement Systems. US: Technical Publications. pp. 4–14. ISBN 978-81-8431-206-5.

- "Definition of SOUND". Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Pilhofer, Michael (2007). Music Theory for Dummies. For Dummies. p. 97. ISBN 9780470167946.

- Elert, Glenn; Timothy Condon (2003). "Frequency Range of Dog Hearing". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

Further reading

- Giancoli, D.C. (1988). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-669201-0.

External links

| Look up frequency or often in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Conversion: frequency to wavelength and back

- Conversion: period, cycle duration, periodic time to frequency

- Keyboard frequencies = naming of notes – The English and American system versus the German system

- Teaching resource for 14-16yrs on sound including frequency

- A simple tutorial on how to build a frequency meter

- Frequency – diracdelta.co.uk – JavaScript calculation.

- A frequency generator with sound, useful for hearing tests