Daly City, California

Daly City (/ˈdeɪli/) is the largest city in San Mateo County, California, United States, with an estimated 2019 population of 106,280.[12] Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, and immediately south of San Francisco, it is named in honor of businessman and landowner John Donald Daly.

Daly City, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

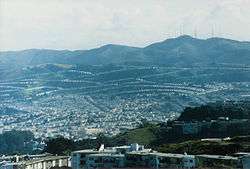

Part of Daly City with San Bruno Mountain and the San Francisco neighborhood of Crocker Amazon in the background | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Gateway to the Peninsula | |

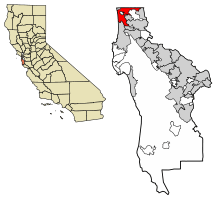

Location of Daly City in San Mateo County, California | |

Daly City, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 37°41′11″N 122°28′06″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | March 22, 1911[1] |

| Named for | John Daly |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Glenn R. Sylvester[2] |

| • City council[2] | Council Members

|

| • State Assembly | Phil Ting (D)[3] |

| • State Senator | Scott Wiener (D)[3] |

| • U. S. Rep. | Jackie Speier (D)[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.64 sq mi (19.78 km2) |

| • Land | 7.64 sq mi (19.78 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 344 ft (105 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 101,123 |

| • Estimate (2019)[8] | 106,280 |

| • Rank | 1st in San Mateo County 66th in California |

| • Density | 13,914.64/sq mi (5,372.15/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes[9] | 94014–94017 |

| Area codes[10][11] | 415/628, 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-17918[7] |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1658369, 2410291[6] |

| Website | www |

History

Archaeological evidence suggests the San Francisco Bay Area has been inhabited as early as 2700 BC.[13] People of the Ohlone language group probably occupied Northern California from at least the year 500 A.D.[14] Though their territory had been claimed by Spain since the early 16th century, they would have relatively little contact with Europeans until 1769, when, as part of an effort to colonize Alta California, an exploration party led by Don Gaspar de Portolá learned of the existence of San Francisco Bay.[15] Seven years later, in 1776, an expedition led by Juan Bautista de Anza selected the site for the Presidio of San Francisco, which José Joaquín Moraga would soon establish. Later the same year, the Franciscan missionary Francisco Palóu founded the Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores).[16] As part of the founding, the priests claimed the land south of the mission for sixteen miles for raising crops and for fodder for cattle and sheep.[17] In 1778, the priests and soldiers marked out a trail to connect San Francisco to the rest of California.[17] At the top of Mission Hill, the priests named the gap between San Bruno Mountain and the hills on the coast La Portezuela ("The Little Door").[17] La Portezuela was later referred to as Daly's Hill, the Center of Daly City, and is now called Top of the Hill.[17]

During Spanish rule, the area between San Bruno Mountain and the Pacific remained uninhabited.[18] Upon independence from Spain, prominent Mexican citizens were granted land parcels to establish large ranches, three of which covered areas now in Daly City and Colma.[18] Rancho Buri Buri was granted to Jose Sanchez in 1835 and covered 14,639 acres (59.24 km2) including parts of modern-day Colma, Burlingame, San Bruno, South San Francisco, and Millbrae.[18][19] Rancho Laguna de la Merced was 2,219 acres (8.98 km2) acres and covered the area around a lake of the same name.[18][19] The third ranch covering parts of the Daly City–Colma area was named Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe la Visitación y Rodeo Viejo and stretched from the Visitacion Valley area in San Francisco, to the city of South San Francisco covering 5,473 acres (22.15 km2).[18][19]

Following the Mexican Cession of California at the end of the Mexican–American War the owners of Rancho Laguna de La Merced tried to claim land between San Bruno Mountain and Lake Merced. An 1853 US government survey declared that the contested area was in fact government property and could be acquired by private citizens. There was a brief land rush as settlers, mainly Irish established ranches and farms in parts of what is now the neighborhoods of Westlake, Serramonte, and the cities of Colma and Pacifica.[20] A decade later, several families left as increase in the fog density killed grain and potato crops. The few remaining families switched to dairy and cattle farming as a more profitable enterprise.[20] In the late 19th century as San Francisco grew and San Mateo County was established, Daly City also gradually grew including homes and schools along the lines for the Southern Pacific railroad.[21] Daly City served as a location where San Franciscans would cross over county lines to gamble and fight.[22] As tensions built in approach to the American Civil War, California was divided between pro-slavery, and Free Soil advocates. Two of the main figures in the debate were US Senator David C. Broderick, a Free Soil advocate, and David S. Terry, who was in favor of extension of slavery into California. Quarreling and political fighting between the two eventually led to a duel in the Lake Merced area at which Terry mortally wounded Broderick, who would die three days later.[23] The site of the duel is marked with two granite shafts where the men stood, and is designated as California Historical Landmark number 19.[24]

On the morning of April 18, 1906 a major earthquake struck just off the coast of Daly City near Mussel Rock.[25] After quake and subsequent fire destroyed many San Franciscans homes, they left to temporary housing on the ranches of the area to the south, including the large one owned by John Daly.[26] Daly had come to the Bay Area in 1853 where he had worked on a dairy farm, and after several years married his bosses' daughter and acquired 250 acres (1.0 km2) at the Top of the Hill area. Over the years Daly's business grew, as did his political clout.[27] When a flood of refugees from the quake came, Daly and other local farmers donated milk and other food items.[28] Daly later subdivided his property, from which several housing tracts emerged.[27]

As some of the refugees established homes in the area, the need for city services grew. This, combined with the fear of annexation by San Francisco and being ignored by San Mateo County, whose seat far to the south left residents feeling ignored, created a demand for incorporation. The first such attempt was proposed in 1908 for incorporation as the city of Vista Grande. Vista Grande would have spanned from the Pacific to the Bay, with San Francisco as its northern border and South San Francisco and the old Rancho Buri Buri as its southern border. The proposal was rejected over the scope of the planned city, which was too broad for many residents.[29] The initial proposal also revealed rifts in the community among the various regions, including the area around the cemeteries, who were excluded from further plans of incorporation.[29] On January 16, 1911, an incorporation committee filed a petition with San Mateo County supervisors to incorporate the City of Daly City. The city would run from San Francisco along the San Bruno Hills until Price and School streets with San Francisco and west to the summit of the San Bruno Hills. The city would have an estimated population of 2,900.[30] On March 18, 1911, a special election was held, with incorporation narrowly succeeding by a vote of 132 to 130.[31]

It remained a relatively small community until the late 1940s, when developer Henry Doelger established Westlake, a major district of homes and businesses, including the Westlake Shopping Center. On March 22, 1957, Daly City was again the epicenter of an earthquake, this one a 5.3 magnitude quake on the San Andreas Fault, which caused some structural damage in Westlake and closed State Route 1 along the Westlake Palisades.[32] In 1963, Daly City annexed the city of Bayshore.[33] The Cow Palace, located in Bayshore and now within the city limits of Daly City, was the site of the following year's Republican National Convention. The Daly City BART station opened on September 11, 1972, providing northern San Mateo County with rail service to downtown San Francisco and other parts of the Bay Area. The line was extended south to Colma in 1996 and then to Millbrae and the San Francisco International Airport in 2003.

In October 1984, Taiwanese American writer Henry Liu was assassinated in his garage in Daly City, allegedly by Kuomintang agents.[34]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.7 square miles (20 km2), all land.

Daly City is bordered by the cities of San Francisco, Brisbane, Pacifica, South San Francisco, and the town of Colma. The city borders several unincorporated areas of San Mateo County. It surrounds Broadmoor, borders San Bruno Mountain State Park, the Olympic Club, and unincorporated areas near Colma.[35] Seismic faults in and near Daly City include the San Andreas Fault, Hillside Fault and Serra Fault. Lake Merced is associated with the city.

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods of Daly City include Westlake, St. Francis Heights, Serramonte, Top of the Hill, Hillside, Crocker, Southern Hills, and Bayshore. Westlake is notable for its distinct architecture and for being among the earliest examples of a planned, large-tract suburb. It was the inspiration for Malvina Reynolds' song, "Little Boxes" and later a coffee-table book and documentary Little Boxes: The Architecture of a Classic Midcentury Suburb.[36] Bayshore, the easternmost neighborhood of Daly City, was once an incorporated city, Bayshore City, until being annexed to Daly City in 1963.[33] Bayshore remains somewhat disconnected from the rest of Daly City; to drive from Bayshore to any other part of Daly City, one must drive through San Francisco via Geneva Avenue or through unincorporated San Mateo County via Guadalupe Canyon Parkway. Several Daly City neighborhoods, such as Crocker, Southern Hills, and Bayshore, share a street grid and similar characteristics with adjacent San Francisco neighborhoods, such as Crocker-Amazon and Visitacion Valley.

Several neighborhoods associated with Daly City lie outside of its city limits. Broadmoor is an unincorporated area completely surrounded by Daly City. Colma is an incorporated town sandwiched between Daly City, South San Francisco, and San Bruno Mountain. These enclaves are in charge of their own police and fire services, but also share some services with Daly City.

Climate

Daly City's climate is similar to San Francisco's climate, with fog occurring in the spring and early-late summer. Summers are cool and dry, whereas winters are merely mild, being not too chilly, and wet.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 3,779 | — | |

| 1930 | 7,838 | 107.4% | |

| 1940 | 9,625 | 22.8% | |

| 1950 | 15,191 | 57.8% | |

| 1960 | 44,791 | 194.9% | |

| 1970 | 66,922 | 49.4% | |

| 1980 | 78,519 | 17.3% | |

| 1990 | 92,311 | 17.6% | |

| 2000 | 103,621 | 12.3% | |

| 2010 | 101,123 | −2.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 106,280 | [8] | 5.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[37] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census reported that Daly City had a population of 101,123.[38] The population density was 13,195.0 people per square mile (5,094.6/km2), placing it 291st in population, among the top 50 in density when smaller populations are included, and 9th in density amongst cities with over 100,000 people.

The racial makeup of Daly City was 56,267 (55.6%) Asian, 23,842 (23.6%) White, 3,600 (3.6%) African American, 805 (0.8%) Pacific Islander, 404 (0.4%) Native American, 11,236 (11.1%) from other races, and 4,969 (4.9%) from two or more races.

It is the largest city with a majority Asian population in the Mainland U.S..

Among the total population of Daly City, 33.2% were Filipino, 15.4% Chinese, 1.8% Burmese, 1.0% Vietnamese, 0.6% Indian, 0.6% Korean, 0.6% Japanese, 0.2% Indonesian, and 0.2% were Thai. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 23,929 persons (23.7%); 9.4% of Daly City's population is of Mexican origin; 4.9% is of Salvadoran, 2.7% Nicaraguan, 1.3% Guatemalan, 0.7% Peruvian, 0.7% Puerto Rican, and 0.5% Honduran heritage.

The Census reported that 100,442 people (99.3% of the population) lived in households, 273 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 408 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 31,090 households, out of which 11,050 (35.5%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 15,883 (51.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 4,667 (15.0%) had a female householder with no husband present, 2,238 (7.2%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,632 (5.2%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 293 (0.9%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 5,855 households (18.8%) were made up of individuals and 2,136 (6.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.23. There were 22,788 families (73.3% of all households); the average family size was 3.63.

The population was spread out with 19,614 people (19.4%) under the age of 18, 10,506 people (10.4%) aged 18 to 24, 29,663 people (29.3%) aged 25 to 44, 27,717 people (27.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 13,623 people (13.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.3 males.

There were 32,588 housing units at an average density of 4,252.2 per square mile (1,641.8/km2), of which 17,565 (56.5%) were owner-occupied, and 13,525 (43.5%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.9%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.2%. 58,239 people (57.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 42,203 people (41.7%) lived in rental housing units.

| Demographic profile[39] | 2010 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 101,123 | 100.0% |

| One Race | 96,154 | 95.1% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 77,194 | 76.3% |

| White alone | 14,031 | 13.9% |

| Black or African American alone | 3,284 | 3.2% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native alone | 115 | 0.1% |

| Asian alone | 55,711 | 55.1% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone | 752 | 0.7% |

| Some other race alone | 471 | 0.5% |

| Two or more races alone | 2,830 | 2.8% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 23,929 | 23.7% |

Daly City is home to the only Karaite synagogue in the United States, Congregation B'nai Israel.[40]

2000

As of the census of 2000, there were 101,514 people, 29,843 households, and 21,847 families residing in the city.[41] The population density was 15,703.8 people per square mile (7,292.1/km2), making it among the most densely populated cities in the country. There were 31,876 housing units at an average density of 5,140.9 per square mile (2,599.1/km2).

There were 29,843 households out of which 35.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.5% were married couples living together, 11.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.0% were non-families. Of all households 22.1% were made up of individuals and 5.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.34 and the average family size was 4.78.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 25.5% under the age of 18, 11.5% from 18 to 24, 32.2% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $60,310, and the median income for a family was $66,365. Males had a median income of $36,227 versus $34,147 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,900. About 5.2% of families and 9.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.4% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.

As of 2010 census figures, 40.7% of Daly City residents are of Filipino descent, the highest concentration of Filipino/Filipino Americans of any mid-sized city in North America. This partly explains Daly City's place in the vernacular as the "Pinoy Capital". Benito M. Vergara, Jr. goes into the details of this history in his ethnography Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City.[42]

Culture

.jpg)

The Cow Palace arena grounds straddle the border with San Francisco and is the home for the annual Grand National Rodeo, Horse & Stock Show.[43] It has hosted diverse events such as concerts by the Beatles, the now-Golden State Warriors and their early appearances in the NBA Finals, the NHL San Jose Sharks hockey team, two short-lived minor league hockey teams (the IHL San Francisco Spiders and ECHL San Francisco Bulls), and two Republican National Conventions (in 1956 and 1964).

Century 20 Daly City is a modern megaplex movie theatre opened in 2002 as part of the Pacific Plaza business and retail development.

Several golf courses are located within or straddle the border with San Francisco. The Olympic Club has hosted the USGA U.S. Open five times, most recently in 2012, and will host both the 2028 PGA Championship and the 2032 Ryder Cup. The private San Francisco Golf Club and Lake Merced Golf Club have part or all of their course in Daly City. The Golden Gate National Recreation Area includes the city's Thornton Beach. The topography of this area (due to the San Andreas fault) is conducive to paragliding and hang gliding.

Since 1934, the Daly City Parks and Recreation Department has been serving Daly City and other neighboring cities. Today, the Department offers over 259 classes, sponsors adult, teen, and youth athletic leagues, aquatic programs, gymnastics, youth and teen services as well as a comprehensive senior adult program, park maintenance, hall rentals, special events, and more.

Giammona Pool and Jefferson Pool are two public indoor swimming pools that provide swimming lessons, aquatic recreation, and host local swimming related organizations including the Daly City Dolphins.

Daly City and neighboring Colma have emerged as shopping meccas for San Francisco residents. A combination of plentiful free parking space (compared to the constrained and expensive parking options in San Francisco) and San Mateo County's historically slightly lower state sales tax rate[44] have contributed to this trend. Many big box retailers that are unable to operate in San Francisco due to real estate prices, space restrictions, or political / community opposition have opened stores in the Serramonte and Westlake neighborhoods. Daly City's shopping centers are Serramonte Center and Westlake Shopping Center.

Government

In the California State Legislature, Daly City is in the 11th Senate District, represented by Democrat Scott Wiener, and in the 19th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Phil Ting.[3] In the United States House of Representatives, Daly City is in California's 14th congressional district, represented by Democrat Jackie Speier.[45] Raymond A. Buenaventura is the mayor.[46] In the United States Senate, Daly City is represented by Democrats Dianne Feinstein and Kamala Harris.

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Daly City has 46,684 registered voters. Of those, 24,175 (51.8%) are registered Democrats, 4,479 (9.6%) are registered Republicans, and 16,487 (35.3%) have declined to state a political party.[47]

Education

There are several public school districts in Daly City. The largest are the Jefferson Elementary School District and Jefferson Union High School District, both of which are headquartered in the city. In addition, there is the Bayshore Elementary School District (two schools), Brisbane School District (Panorama School in Daly City), and South San Francisco Unified School District (two schools in Daly City). Daly City has two high schools: Westmoor High School and Jefferson High School, plus a continuation school, Thornton High School and an adult school, Jefferson Adult Education. Daly City is also home to two Catholic parochial schools: Our Lady of Perpetual Help on Top-Of-The-Hill and Our Lady of Mercy in Westlake. The city has four Peninsula Library System branches.

Transportation

Daly City's highway infrastructure includes State Routes 1, 35, and 82, and Interstate 280. Interstate 280, which bisects Daly City, is a primary transportation corridor linking San Francisco with San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.

The U.S. Census Bureau has identified Daly City as among the cities with the highest transit ridership. Public transportation is provided by SamTrans, BART (at the Daly City Station and the Colma Station, which abuts the Daly City limits), and some San Francisco Muni lines. Daly City is approximately 8 miles south-west of downtown San Francisco and the San Francisco International Airport is 9 miles south-east of Daly City; both are easily accessible by freeway or BART. In the 1980s planning was conducted for the BART extension south from San Francisco, the first step being the Daly City Tailtrack Project, upon which turnaround project the San Francisco Airport Extension would later build.[48]

Sister city

Notable people

- David Brown, bass player for the band Santana

- Mike Carroll, professional skateboarder

- John Madden, NFL player, Hall of Fame coach and sportscaster, graduated from Jefferson High School in 1954[50][51]

- Dave Pelzer, author of several books, including the memoir A Child Called "It"

- John Robinson, national championship-winning coach at USC and for the Los Angeles Rams

- Sam Rockwell, Academy Award-winning actor, born at Seton Medical Center on November 5, 1968[52]

- Death Angel, a 1980s Bay Area Thrash Metal band

- Stephen B. Seager MD, Westmoor High School Class of 1968, Physician, CNN Mental Health Contributor, Author "Behind the Gates of Gomorrah" Simon and Schuster, 2015, Filmmaker "Urban Inferno: the Night Santa Rosa Burned" 2017

See also

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City Officials". City of Daly City, California. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- "California's 14th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "City of Daly City". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- "Daly City (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- "North American Numbering Plan Letter" (PDF) (Press release). Bellcore. November 22, 1996. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- "NANP Administration System". North American Numbering Plan Administration. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Stewart, Suzanne B (November 2003). "Archaeological Research Issues For The Point Reyes National Seashore - Golden Gate National Recreation Area" (PDF). Sonoma State University - Anthropological Studies Center. p. 100. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Levy, Richard (1978). "Costanoan". In William C. Sturtevant and Robert F. Heizer (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. 8. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 486. OL 23238489M.

Linguistic evidence suggests that the ancestors of the Costanoan moved into the San Francisco and Monterey Bay areas about A.D. 500. ... The above postulated movement of Costanoan languages into the San Francisco area seems to coincide with the appearance of the Late Horizon artifact assemblages in archeological sites in the San Francisco bay region.

- "Visitors: San Francisco Historical Information". City and County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Edward F. O'Day (October 1926). "The Founding of San Francisco". San Francisco Water. Spring Valley Water Authority. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- (Chandler 1973, p. 1)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 2)

- "Mexican Land Grants / Ranchos San Mateo County". Earth Sciences & Map Library University of California, Berkeley. Regents of the University of California. June 16, 2003. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- (Chandler 1973, p. 5)

- (Gillespie 2003, p. 11)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 17)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 18)

- "San Mateo". Office of Historic State Preservation California State Parks. 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

NO. 19 BRODERICK-TERRY DUELING PLACE ... The site is marked with a monument and granite shafts where the two men stood.

- Kim, Ryan (April 11, 2004). "DALY CITY / Officials unmoved by quake notoriety / Plan to note change of 1906 epicenter lacking support". The San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. pp. B1. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- (Chandler 1973, p. 27)

- (Gillespie 2003, p. 8)

- (Chandler 1973, pp. 27–28)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 79)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 83)

- (Chandler 1973, p. 84)

- "Historic Earthquakes - 1957 March 22 19:44:21 UTC Magnitude 5.3". Earthquake Hazards Program. US Geological Survey. January 30, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- History, Daly City Police Department

- Bishop, Katherine (March 9, 1988). "California Jury Is Told Defendant Admitted Slaying Journalist". The New York Times. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- Commission on Disabilities | San Mateo Health System Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Smco-cod.org. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- "Filmmakers to release documentary on influential Daly City developer". The San Francisco Examiner. December 15, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Daly City city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "Demographic Profile Bay Area Census".

- "The Karaite Jews of America". The Karaite Jews of America. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Daly City city, California - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder". 2000 Census. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City Archived October 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- Grand National Rodeo. Grand National Rodeo. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- California City and County Sales and Use Tax Rates - Cities, Counties and Tax Rates - California State Board of Equalization Archived June 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Boe.ca.gov (June 17, 2013). Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- "California's 14th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- "City Officials". www.dalycity.org. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- C. Michael Hogan, Kay Wilson, M. Papineau et al., Environmental Impact Statement for the BART Daly City Tailtrack Project, Earth Metrics, published by the U.S Urban Mass Transit Administration and the Bay Area Rapid Transit District 1984

- "Sister Cities". The Local Government of Quezon City. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "Alumni Roster". Jefferson High School. August 29, 2001. Archived from the original on May 15, 2002. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- BARBER, PHIL (April 17, 2009). "Timeline of John Madden's life and career". Santa Rosa Press Democrat. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- "California, Birth Index, 1905-1995". FamilySearch. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

Further reading

- Chandler, Samuel (September 1973). Gateway to the Peninsula. Daly City: City of Daly City. OCLC 799903. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, Samuel C. (1979). La Peninsula: Daly City-Colma Leaves of History. San Mateo: San Mateo County Historical Association. OCLC 54057606.

- Chandler, Samuel C. (ed.). Biographies of Daly City Pioneers. Daly City: Daly City Public Library. OCLC 51566082.

- Diran, Edward (1991). Cow Palace, Great Moments: Cow Palace Tales. San Mateo, California: Western Book/Journal Press. ISBN 978-0-936029-27-6. OCLC 24655738.

- Forbes, Alan A (1968). The American local government spectrum and Daly City, California as seen by an outsider. Daly City: Daly City Public Library. OCLC 54676237.

- Gillespie, Bunny (2003). Daly City. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2867-0. OCLC 53875125.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillespie, Bunny (2008). Westlake. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5911-7. OCLC 261222565.

- Keil, Rob (2006). Little Boxes: The Architecture of a Classic Midcentury Suburb. Daly City, California: Advection Media. ISBN 978-0-9779236-4-9.

- Pisares, Elizabeth H. (1999). Daly City is My Nation: Race, Imperialism and the Claiming of Pinay/ Pinoy Identities in Filipino American Culture (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. OCLC 44992420.

- Vergara, Benito M., Jr. (2009). Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City. Asian American History and Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-665-0.

- History of Daly City from the Daly City Record and the Tattler: Dec. 25, 1915. Daly City: Daly City Public Library. OCLC 54676267.

- Verducci, Richard A (1974). The City of Daly City California. Daly City: Daly City Public Library. OCLC 54682157.