Reindeer

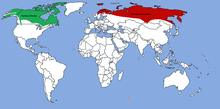

The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), also known as the caribou in North America,[3] is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, sub-Arctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of northern Europe, Siberia, and North America.[2] This includes both sedentary and migratory populations. Rangifer herd size varies greatly in different geographic regions. The Taimyr herd of migrating Siberian tundra reindeer (R. t. sibiricus) in Russia is the largest wild reindeer herd in the world,[4][5] varying between 400,000 and 1,000,000. What was once the second largest herd is the migratory boreal woodland caribou (R. t. caribou) George River herd in Canada, with former variations between 28,000 and 385,000. As of January 2018, there are fewer than 9,000 animals estimated to be left in the George River herd, as reported by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.[6] The New York Times reported in April 2018 of the disappearance of the only herd of southern mountain caribou in the contiguous United States with an expert calling it "functionally extinct" after the herd's size dwindled to a mere three animals.[7]

| Reindeer or caribou | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reindeer in Norway | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Tribe: | Rangiferini |

| Genus: | Rangifer Charles Hamilton Smith, 1827 |

| Species: | R. tarandus |

| Binomial name | |

| Rangifer tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

| Reindeer range: North American (green) and Eurasian (red) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cervus tarandus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Rangifer varies in size and colour from the smallest, the Svalbard reindeer, to the largest, the boreal woodland caribou. The North American range of caribou extends from Alaska through Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut into the boreal forest and south through the Canadian Rockies and the Columbia and Selkirk Mountains.[8] The barren-ground caribou, Porcupine caribou, and Peary caribou live in the tundra, while the shy boreal woodland caribou prefer the boreal forest. The Porcupine caribou and the barren-ground caribou form large herds and undertake lengthy seasonal migrations from birthing grounds to summer and winter feeding grounds in the tundra and taiga. The migrations of Porcupine caribou herds are among the longest of any mammal.[8] Barren-ground caribou are also found in Kitaa in Greenland, but the larger herds are in Alaska, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut.[9]

Some subspecies are rare and at least one has already become extinct: the Queen Charlotte Islands caribou of Canada.[10][11] Historically, the range of the sedentary boreal woodland caribou covered more than half of Canada[12] and into the northern States in the U.S. Woodland caribou have disappeared from most of their original southern range and were designated as threatened in 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).[13] Environment Canada reported in 2011 that there were approximately 34,000 boreal woodland caribou in 51 ranges remaining in Canada.(Environment Canada, 2011b).[14] Siberian tundra reindeer herds are in decline, and Rangifer tarandus is considered to be vulnerable by the IUCN.

Arctic peoples have depended on caribou for food, clothing, and shelter, such as the Caribou Inuit, the inland-dwelling Inuit of the Kivalliq Region in northern Canada, the Caribou Clan in Yukon, the Inupiat, the Inuvialuit, the Hän, the Northern Tutchone, and the Gwich'in (who followed the Porcupine caribou for millennia). Hunting wild reindeer and herding of semi-domesticated reindeer are important to several Arctic and sub-Arctic peoples such as the Duhalar for meat, hides, antlers, milk, and transportation.[15] The Sami people (Sápmi) have also depended on reindeer herding and fishing for centuries.[16]:IV[17]:16[16]:IV In Sápmi, reindeer pull pulks.[18]

Male and female reindeer can grow antlers annually, although the proportion of females that grow antlers varies greatly between population and season.[19] Antlers are typically larger on males. In traditional festive legend, Santa Claus's reindeer pull a sleigh through the night sky to help Santa Claus deliver gifts to good children on Christmas Eve.

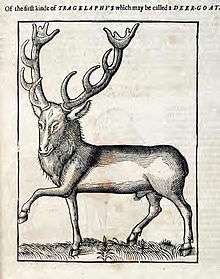

Naming

Carl Linnaeus chose the name Rangifer for the reindeer genus, which Albertus Magnus used in his De animalibus, fol. Liber 22, Cap. 268: "Dicitur Rangyfer quasi ramifer". This word may go back to the Saami word raingo.[20] Linnaeus chose the word tarandus as the specific epithet, making reference to Ulisse Aldrovandi's Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia fol. 859–863, Cap. 30: De Tarando (1621). However, Aldrovandi and Konrad Gesner[21] – thought that rangifer and tarandus were two separate animals.[22] In any case, the tarandos name goes back to Aristotle and Theophrastus.

The use of the terms reindeer and caribou for essentially the same animal can cause confusion, but the International Union for Conservation of Nature clearly delineates the issue: "The world's Caribou and Reindeer are classified as a single species Rangifer tarandus. Reindeer is the European name for the species while in North America, the species is known as Caribou."[2] The word rein is of Norse origin. The word deer was originally broader in meaning but became more specific over time. In Middle English, der meant a wild animal of any kind, in contrast to cattle.[23] The word caribou comes through French, from the Mi'kmaq qalipu, meaning "snow shoveler" and referring to its habit of pawing through the snow for food.[24]

Because of its importance to many cultures, Rangifer tarandus and some of its subspecies have names in many languages. Inuktitut is spoken in the eastern Arctic, and the caribou is known by the name tuktu.[25][26][27] The Gwich’in people have over two dozen distinct caribou-related words.[28]

Names for reindeer in languages spoken throughout their (former) native range:

| Name | Meaning | Language | People | Region | R. t. subspecies and ecotype | Language family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsaa , Eter | Mongolian | Altaic: Mongolian | ||||

| qalipu | one who paws | Mi'kmaq | Mi'kmaq | what is now eastern Canada and the northeastern U.S. | R. t. caribou | Algonquian |

| magôlibo | one who paws | Abenaki | Abenaki | R. t. caribou | Algonquian | |

| mokalip | one who paws | Malecite-Passamaquoddy | Maliseet, Passamaquoddy | R. t. caribou | Algonquian | |

| atíhko | caribou | Woods Cree | Cree | Northern Manitoba | R. t. groenlandicus | Algonquian |

| atihkw | Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi | R. t. caribou | Algonquian | |||

| bedzeyh[29] | Koyukon | Koyukon | Alaska | R. t. granti (the Western Arctic caribou herd) | Athabaskan | |

| vadzaih[28] | caribou | Gwich’in | Gwich’in | the Northwest Territories | R. t. groenlandicus (the Bluenose East and Bluenose West barren-ground caribou herds), R. t. granti (the Porcupine caribou herd) | Athabaskan |

| wëdzey[30] | Hän | Hän | Athabaskan | |||

| tuktu[31] | Inuktitut | Inuit | Nunavut (the barren-ground caribou population) and Labrador | R. t. groenlandicus, R. t. caboti | Eskimo–Aleut | |

| tuttu[29] | Inupiaq | Inupiat people | Alaska | R. t. granti (the Western Arctic caribou herd) | Eskimo–Aleut | |

| tuntu[29] | Yup'ik | Yup'ik | Alaska | R. t. granti (the Western Arctic caribou herd) | Eskimo–Aleut | |

| илэ (ile) | Tundra Yukaghir | Yukaghir people | ||||

| ӄораӈы (qoraŋə) | Chukchi | Chukchi people | Chukotko-Kamchatkan | |||

| ӄояӈа (qojaŋa) | Koryak | Koryak people | Chukotka-Kamchatkan | |||

| ӄураӈа (quraŋa) | Alyutor | Alyutor people | ||||

| ӄуйаӄуй (qujaquj) | Kerek | Kerek | ||||

| ӄос (qos) | Itelmen | Itelmens | ||||

| ора̇н (orȧn) | Even | Evens | Tungusic | |||

| оро̄н (orōn) | Nanai | Nanai people | Tungusic | |||

| оро (oro) | Udehe | Udehe | Tungusic | |||

| оро (oro) | Ulch | Ulch | TUngusic | |||

| boazu[32] | Northern Sami | Sami people | Northern Scandinavia | Uralic | ||

| bå̄tsoj | Pite Sami | Sami people | Uralic | |||

| boatsoj | Lule Sami | Sami people | Uralic | |||

| båatsoe | Southern Sami | Sami People | Uralic | |||

| peura (general term), poro (domesticated) | Finnish | Finnish people | Uralic | |||

| reinsdyr | Norwegian | Norwegians | Indo-European | |||

| ren | Swedish | Swedes | Indo-European | |||

| се́верный оле́нь (sévernyj olénʹ ) | "northern deer" | Russian | Russians | Indo-European |

Taxonomy and evolution

The species' taxonomic name, Rangifer tarandus, was defined by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The woodland caribou subspecies' taxonomic name Rangifer tarandus caribou was defined by Gmelin in 1788.

Based on Banfield's often-cited A Revision of the Reindeer and Caribou, Genus Rangifer (1961),[33] R. t. caboti (the Labrador caribou), R. t. osborni (Osborn's caribou—from British Columbia) and R. t. terraenovae (the Newfoundland caribou) were considered invalid and included in R. t. caribou.

Some recent authorities have considered them all valid, even suggesting that they are quite distinct. In their book entitled Mammal Species of the World, American zoologist Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn Reeder agree with Valerius Geist, specialist on large North American mammals, that this range actually includes several subspecies.[34][35][36][Notes 1]

Geist (2007) argued that the "true woodland caribou, the uniformly dark, small-maned type with the frontally emphasised, flat-beamed antlers", which is "scattered thinly along the southern rim of North American caribou distribution" has been incorrectly classified. He affirms that the "true woodland caribou is very rare, in very great difficulties and requires the most urgent of attention."[34]

In 2005, an analysis of mtDNA found differences between the caribou from Newfoundland, Labrador, southwestern Canada and southeastern Canada, but maintained all in R. t. caribou.[37]

Mallory and Hillis argued that, "Although the taxonomic designations reflect evolutionary events, they do not appear to reflect current ecological conditions. In numerous instances, populations of the same subspecies have evolved different demographic and behavioural adaptations, while populations from separate subspecies have evolved similar demographic and behavioural patterns... "[U]nderstanding ecotype in relation to existing ecological constraints and releases may be more important than the taxonomic relationships between populations."[38]

Current classifications of Rangifer tarandus, either with prevailing taxonomy on subspecies, designations based on ecotypes, or natural population groupings, fail to capture "the variability of caribou across their range in Canada" needed for effective species conservation and management.[39] "Across the range of a species, individuals may display considerable morphological, genetic, and behavioural variability reflective of both plasticity and adaptation to local environments."[40] COSEWIC developed Designated Unit (DU) attribution to add to classifications already in use.[39]

Subspecies

The canonical Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.) recognises 14 subspecies, two of which are extinct.[9]

| subspecies | name | sedentary/migratory | division[9] | range | weight of male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. t. buskensis[35] (1915) | Busk reindeer | woodland[9] | Russia and the neighbouring regions | no data | |

| R. t. caboti** (G. M. Allen, 1914)[9][Notes 2][34][35] | Labrador caribou | tundra | Quebec and Labrador, Canada | no data | |

| R. t. caribou (Gmelin, 1788)[33] | Woodland caribou; includes boreal woodland caribou, migratory woodland caribou and mountain woodland caribou | sedentary[Notes 3] | boreal forest | Southern Canada and the northwestern U.S. mainland[41] | largest subspecies |

| R. t. granti[33] | Porcupine caribou or Grant's caribou | migratory | tundra | Alaska, United States and the Yukon, Canada | |

| R. t. fennicus (Lönnberg, 1909) | Finnish forest reindeer | woodland[9] | Northwestern Russia and Finland[18][41] | 150–250 kg (330–550 lb) | |

| R. t. groenlandicus (Borowski, 1780)[33] | Barren-ground caribou | migratory | tundra | the High Arctic islands of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, Canada and western Greenland | 150 kg (330 lb) |

| R. t. osborni** (J. A. Allen, 1902)[Notes 2][34][35] | Osborn's caribou | woodland | British Columbia, Canada | no data | |

| R. t. pearsoni (Lydekker, 1903)[35] | Novaya Zemlya reindeer | island subspecies make local movements | The Novaya Zemlya archipelago of Russia[41] | no data | |

| R. t. pearyi (J. A. Allen, 1902)[33] | Peary caribou | island subspecies make local movements | The High Arctic islands of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, Canada[41] | smallest North American subspecies | |

| R. t. phylarchus (Hollister, 1912)[35] | Kamchatkan reindeer | woodland[9] | the Kamchatka Peninsula and the regions bordering the Sea of Okhotsk, Russia[41] | no data | |

| R. t. platyrhynchus (Vrolik, 1829) | Svalbard reindeer | island subspecies make local movements | the Svalbard archipelago of Norway[41] | smallest subspecies | |

| R. t. sibiricus (Murray, 1866)[35] | Siberian tundra reindeer | tundra | Siberia and Russia.[41] Franz Josef Land during the Holocene from >6400-1300 cal. BP (locally extinct). [42] | no data | |

| R. t. tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Mountain reindeer or Norwegian reindeer | tundra or mountain | the Arctic tundra of the Fennoscandian Peninsula in Norway[18][41] and Austfirðir in Iceland (introduced).[43] | no data | |

| R. t. terraenovae** (Bangs, 1896)[9][Notes 2][34][35] | Newfoundland caribou | woodland | Newfoundland, Canada | no data | |

| R. t. valentinae**[9] | Siberian forest reindeer | boreal forest | the Ural Mountains, Russia and the Altai Mountains, Mongolia[41] | no data |

| subspecies | name | sedentary/migratory | division | range | weight of male | extinct since |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. t. dawsoni (Thompson-Seton, 1900)[33] | †Queen Charlotte Islands caribou or Dawson's caribou | extinct | woodland | Graham Island of the Queen Charlotte Islands archipelago, off the coast of British Columbia, Canada | no data | 1908 |

| R. t. eogroenlandicus | †Arctic reindeer or East Greenland caribou | extinct | tundra | eastern Greenland | no data | 1900 |

The table above includes R. tarandus caboti (Labrador caribou), R. tarandus osborni (Osborn's caribou – from British Columbia) and R. tarandus terraenovae (Newfoundland caribou). Based on a review in 1961,[33] these were considered invalid and included in R. tarandus caribou, but some recent authorities have considered them all valid, even suggesting that they are quite distinct.[34][35] An analysis of mtDNA in 2005 found differences between the caribou from Newfoundland, Labrador, southwestern Canada and southeastern Canada, but maintained all in R. tarandus caribou.[37]

There are seven subspecies of reindeer in Eurasia, of which only two are found in Fennoscandia: the mountain reindeer (R. t. tarandus) in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia and the Finnish forest reindeer (R. t. fennicus) in Finland and Russia.[18]

Two subspecies are found only in North America: the Porcupine caribou (R. t. granti) and the Peary caribou (R. t. pearyi). The barren-ground caribou (R. t. groenlandicus) is found in western Greenland, but the larger herds are in Alaska, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.[9]

According to Grubb, based on Banfield[33] and considerably modified by Geist,[44] these subspecies and divisions are considered valid:[9] the caribou or woodland caribou division, which includes R. t. buskensis, R. t. caribou, R. t. dawsoni, R. t. fennicus, R. t. phylarchus and R. t. valentinae (R. t. osborni is a transitional subspecies between the caribou and tarandus divisions), the tarandus or tundra reindeer division, which includes R. t. caboti, R. t. groenlandicus, R. t. pearsoni, R. t. sibiricus and R. t. terraenovae and the platyrhynchus or dwarf reindeer division, which includes R. t. pearyi and R. t. platyrhynchus.

Some of the Rangifer tarandus subspecies may be further divided by ecotype depending on several behavioural factors – predominant habitat use (northern, tundra, mountain, forest, boreal forest, forest-dwelling, woodland, woodland (boreal), woodland (migratory) or woodland (mountain), spacing (dispersed or aggregated) and migration patterns (sedentary or migratory).[45][46][47]

The "glacial-interglacial cycles of the upper Pleistocene had a major influence on the evolution" of Rangifer tarandus and other Arctic and sub-Arctic species. Isolation of Rangifer tarandus in refugia during the last glacial – the Wisconsin in North America and the Weichselian in Eurasia-shaped "intraspecific genetic variability" particularly between the North American and Eurasian parts of the Arctic.[3]

In 1986 Kurtén reported that the oldest reindeer fossil was an "antler of tundra reindeer type from the sands of Süssenborn" in the Pleistocene (Günz) period (680,000 to 620,000 BP).[1] By the 4-Würm period (110,000–70,000 to 12,000–10,000 BP) its European range was very extensive. Reindeer occurred in

... Spain, Italy and southern Russia. Reindeer [was] particularly abundant in the Magdalenian deposits from the late part of the 4-Wurm just before the end of the Ice Age: at that time and at the early Mesolithic it was the game animal for many tribes. The supply began to get low during the Mesolithic, when reindeer retired to the north.

— Kurtén 1968:170

"In spite of the great variation, all the Pleistocene and living reindeer belong to the same species."[1]

Humans started hunting reindeer in the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods and humans are today the main predator in many areas. Norway and Greenland have unbroken traditions of hunting wild reindeer from the last glacial period until the present day. In the non-forested mountains of central Norway, such as Jotunheimen, it is still possible to find remains of stone-built trapping pits, guiding fences and bow rests, built especially for hunting reindeer. These can, with some certainty, be dated to the Migration Period, although it is not unlikely that they have been in use since the Stone Age.

Physical characteristics

Antlers

In most populations both sexes grow antlers; the reindeer is the only cervid species in which females grow them as well as males.[48] Androgens play essential role in cervids antler formation. The antlerogenic genes in reindeer have more sensitivity to androgens in comparison with other cervids.[49][50]

There is considerable variation between subspecies in the size of the antlers (e.g. they are rather small and spindly in the northernmost subspecies),[51] but on average the bull reindeer's antlers are the second largest of any extant deer, after the moose. In the largest subspecies, the antlers of large males can range up to 100 cm (39 in) in width and 135 cm (53 in) in beam length. They have the largest antlers relative to body size among living deer species.[48] Antler size measured in number of points reflects the nutritional status of the reindeer and climate variation of its environment.[52][53] The number of points on male reindeer increases from birth to five years of age and remains relatively constant from then on.[54] "In male caribou, antler mass (but not the number of tines) varies in concert with body mass."[55][56] While antlers of bull woodland caribou are typically smaller than barren-ground caribou, they can be over one metre across. They are flattened, compact and relatively dense.[14] Geist describes them as frontally emphasised, flat-beamed antlers.[57] Woodland caribou antlers are thicker and broader than those of the barren-ground caribou and their legs and heads are longer.[14] Quebec-Labrador bull caribou antlers can be significantly larger and wider than other woodland caribou. Central barren-ground bull caribou are perhaps the most diverse in configuration and can grow to be very high and wide. Mountain caribou are typically the most massive with the largest circumference measurements.

The antlers' main beams begin at the brow "extending posterior over the shoulders and bowing so that the tips point forward. The prominent, palmate brow tines extend forward, over the face."[58] The antlers typically have two separate groups of points, lower and upper.

Antlers begin to grow on male reindeer in March or April and on female reindeer in May or June. This process is called antlerogenesis. Antlers grow very quickly every year on the males. As the antlers grow, they are covered in thick velvet, filled with blood vessels and spongy in texture. The antler velvet of the barren-ground caribou and boreal woodland caribou is dark chocolate brown.[59] The velvet that covers growing antlers is a highly vascularised skin. This velvet is dark brown on woodland or barren-ground caribou and slate-grey on Peary caribou and the Dolphin-Union caribou herd.[58][60][61] Velvet lumps in March can develop into a rack measuring more than a metre in length (3 ft) by August.[62]:88

When the antler growth is fully grown and hardened, the velvet is shed or rubbed off. To the Inuit, for whom the caribou is a "culturally important keystone species", the months are named after landmarks in the caribou life cycle. For example, amiraijaut in the Igloolik region is "when velvet falls off caribou antlers."[63]

Male reindeer use their antlers to compete with other males during the mating season. In describing woodland caribou, SARA wrote, "During the rut, males engage in frequent and furious sparring battles with their antlers. Large males with large antlers do most of the mating."[64] Reindeer continue to migrate until the bull reindeer have spent the back fat.[63][65][66]

In late autumn or early winter after the rut, male reindeer lose their antlers, growing a new pair the next summer with a larger rack than the previous year. Female reindeer keep their antlers until they calve. In the Scandinavian populations, old males' antlers fall off in December, young males' fall off in the early spring and females' fall off in the summer.

When bull reindeer shed their antlers in early to midwinter, the antlered female reindeer acquire the highest ranks in the feeding hierarchy, gaining access to the best forage areas. These cows are healthier than those without antlers.[67] Calves whose mothers do not have antlers are more prone to disease and have a significantly higher mortality.[67] Females in good nutritional condition, for example, during a mild winter with good winter range quality, may grow new antlers earlier as antler growth requires high intake.[67]

According to a respected Igloolik elder, Noah Piugaattuk, who was one of the last outpost camp leaders,[68] caribou (tuktu) antlers[63]

...get detached every year… Young males lose the velvet from the antlers much more quickly than female caribou even though they are not fully mature. They start to work with their antlers just as soon as the velvet starts to fall off. The young males engage in fights with their antlers towards autumn…soon after the velvet had fallen off they will be red, as they start to get bleached their colour changes… When the velvet starts to fall off the antler is red because the antler is made from blood. The antler is the blood that has hardened, in fact the core of the antler is still bloody when the velvet starts to fall off, at least close to the base.

— Elder Noah Piugaattuk of Igloolik cited in "Tuktu — Caribou" (2002) "Canada's Polar Life

According to the Igloolik Oral History Project (IOHP), "Caribou antlers provided the Inuit with a myriad of implements, from snow knives and shovels to drying racks and seal-hunting tools. A complex set of terms describes each part of the antler and relates it to its various uses".[63] Currently, the larger racks of antlers are used by Inuit as materials for carving. Iqaluit-based Jackoposie Oopakak's 1989 carving, entitled Nunali, which means ""place where people live", and which is part of the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada, includes a massive set of caribou antlers on which he has intricately carved the miniaturised world of the Inuit where "Arctic birds, caribou, polar bears, seals, and whales are interspersed with human activities of fishing, hunting, cleaning skins, stretching boots, and travelling by dog sled and kayak...from the base of the antlers to the tip of each branch".[69]

Pelt

The colour of the fur varies considerably, both between individuals and depending on season and subspecies. Northern populations, which usually are relatively small, are whiter, while southern populations, which typically are relatively large, are darker. This can be seen well in North America, where the northernmost subspecies, the Peary caribou, is the whitest and smallest subspecies of the continent, while the southernmost subspecies, the boreal woodland caribou, is the darkest and largest.[51]

The coat has two layers of fur: a dense woolly undercoat and longer-haired overcoat consisting of hollow, air-filled hairs.[70][Notes 4] Fur is the primary insulation factor that allows reindeer to regulate their core body temperature in relation to their environment, the thermogradient, even if the temperature rises to 100 °F (38 °C).[71] In 1913 Dugmore noted how the woodland caribou swim so high out of the water, unlike any other mammal, because their hollow, "air-filled, quill-like hair" acts as a supporting "life jacket."[72]

A darker belly color may be caused by two mutations of MC1R. They appear to be more common in domestic herds.[73]

Heat exchange

Blood moving into the legs is cooled by blood returning to the body in a countercurrent heat exchange (CCHE), a highly efficient means of minimising heat loss through the skin's surface. In the CCHE mechanism, in cold weather, blood vessels are closely knotted and intertwined with arteries to the skin and appendages that carry warm blood with veins returning to the body that carry cold blood causing the warm arterial blood to exchange heat with the cold venous blood. In this way, their legs for example are kept cool, maintaining the core body temperature nearly 30 °C (54 °F) higher with less heat lost to the environment. Heat is thus recycled instead of being dissipated. The "heart does not have to pump blood as rapidly in order to maintain a constant body core temperature and thus, metabolic rate." CCHE is present in animals like reindeer, fox and moose living in extreme conditions of cold or hot weather as a mechanism for retaining the heat in (or out of) the body. These are countercurrent exchange systems with the same fluid, usually blood, in a circuit, used for both directions of flow.[74]

Reindeer have specialised counter-current vascular heat exchange in their nasal passages. Temperature gradient along the nasal mucosa is under physiological control. Incoming cold air is warmed by body heat before entering the lungs and water is condensed from the expired air and captured before the reindeer's breath is exhaled, then used to moisten dry incoming air and possibly be absorbed into the blood through the mucous membranes.[75] Like moose, caribou have specialised noses featuring nasal turbinate bones that dramatically increase the surface area within the nostrils.

Hooves

The reindeer has large feet with crescent-shaped, cloven hooves for walking in snow or swamps. According to the Species at Risk Public Registry (SARA), woodland[64]

"Caribou have large feet with four toes. In addition to two small ones, called "dew claws," they have two large, crescent-shaped toes that support most of their weight and serve as shovels when digging for food under snow. These large concave hooves offer stable support on wet, soggy ground and on crusty snow. The pads of the hoof change from a thick, fleshy shape in the summer to become hard and thin in the winter months, reducing the animal’s exposure to the cold ground. Additional winter protection comes from the long hair between the "toes"; it covers the pads so the caribou walks only on the horny rim of the hooves."

— SARA 2014

Reindeer hooves adapt to the season: in the summer, when the tundra is soft and wet, the footpads become sponge-like and provide extra traction. In the winter, the pads shrink and tighten, exposing the rim of the hoof, which cuts into the ice and crusted snow to keep it from slipping. This also enables them to dig down (an activity known as "cratering") through the snow to their favourite food, a lichen known as reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiferina).[76][77]

Size

_Rangifer_arcticus_groenlandicus_skull.png)

The females usually measure 162–205 cm (64–81 in) in length and weigh 80–120 kg (180–260 lb).[78] The males (or "bulls" as they are often called) are typically larger (to an extent which varies between the different subspecies), measuring 180–214 cm (71–84 in) in length and usually weighing 159–182 kg (351–401 lb).[78] Exceptionally large males have weighed as much as 318 kg (701 lb).[78] Weight varies drastically between seasons, with males losing as much as 40% of their pre-rut weight.[79]

Shoulder height Is usually 85 to 150 cm (33 to 59 in), and the tail is 14 to 20 cm (5.5 to 7.9 in) long.

The reindeer from Svalbard are the smallest. They are also relatively short-legged and may have a shoulder height of as little as 80 cm (31 in),[80] Norwegian Polar Institute.</ref thereby following [[Allen's rule]]. === Clicking sound === The knees of many subspecies of reindeer are adapted to produce a clicking sound as they walk.<ref name=clicking>Banfield AWF (1966) "The caribou", pp. 25–28 in The Unbelievable Land. Smith I.N. (ed.) Ottawa: Queen's Press, cited in Bro-Jørgensen, J; Dabelsteen, T (2008). "Knee-clicks and visual traits indicate fighting ability in eland antelopes: Multiple messages and back-up signals". BMC Biology. 6: 47. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-47. PMC 2596769. PMID 18986518.</ref> The sounds originate in the tendons of the knees and may be audible from ten meters away. The frequency of the knee-clicks is one of a range of signals that establish relative positions on a dominance scale among reindeer. "Specifically, loud knee-clicking is discovered to be an honest signal of body size, providing an exceptional example of the potential for non-vocal acoustic communication in mammals."[81] The clicking sound made by reindeer as they walk is caused by small tendons slipping over bone protuberances (sesamoid bones) in their feet.[82][83] The sound is made when a reindeer is walking or running, occurring when the full weight of the foot is on the ground or just after it is relieved of the weight.[72]

Eyes

A study by researchers from University College London in 2011 revealed that reindeer can see light with wavelengths as short as 320 nm (i.e. in the ultraviolet range), considerably below the human threshold of 400 nm. It is thought that this ability helps them to survive in the Arctic, because many objects that blend into the landscape in light visible to humans, such as urine and fur, produce sharp contrasts in ultraviolet.[84] The tapetum lucidum of Arctic reindeer eyes changes in colour from gold in summer to blue in winter to improve their vision during times of continuous darkness, and perhaps enable them to better spot predators.[85]

Biology and behaviour

Seasonal body composition

Reindeer have developed adaptations for optimal metabolic efficiency during warm months as well as for during cold months.[86] The body composition of reindeer varies highly with the seasons. Of particular interest is the body composition and diet of breeding and non-breeding females between seasons. Breeding females have more body mass than non-breeding females between the months of March and September with a difference of around 10 kg more than non-breeding females. From November to December, non-breeding females have more body mass than breeding females, as non-breeding females are able to focus their energies towards storage during colder months rather than lactation and reproduction. Body masses of both breeding and non-breeding females peaks in September. During the months of March through April, breeding females have more fat mass than the non-breeding females with a difference of almost 3 kg. After this however, nonbreeding females on average have a higher fat mass than the breeding females.[87]

The environmental variations play a large part in reindeer nutrition, as winter nutrition is crucial to adult and neonatal survival rates.[88] Lichens are a staple during the winter months as they are a readily available food source, which reduces the reliance on stored body reserves.[87] Lichens are a crucial part of the reindeer diet; however, they are less prevalent in the diet of pregnant reindeer compared to non-pregnant individuals. The amount of lichen in a diet is found more in non-pregnant adult diets than pregnant individuals due to the lack of nutritional value. Although lichens are high in carbohydrates, they are lacking in essential proteins that vascular plants provide. The amount of lichen in a diet decreases in latitude, which results in nutritional stress being higher in areas with low lichen abundance.[89]

Reproduction and life-cycle

Reindeer mate in late September to early November and the gestation period is about 228–234 days.[90] During the mating season, males battle for access to females. Two males will lock each other's antlers together and try to push each other away. The most dominant males can collect as many as 15–20 females to mate with. A male will stop eating during this time and lose much of his body reserves.[91]

To calve, "females travel to isolated, relatively predator-free areas such as islands in lakes, peatlands, lakeshores, or tundra."[64] As females select the habitat for the birth of their calves, they are more wary than males.[90] Dugmore noted that, in their seasonal migrations, the herd follows a doe for that reason.[72] Newborns weigh on average 6 kg (13 lb).[79] In May or June the calves are born.[90] After 45 days, the calves are able to graze and forage, but continue suckling until the following autumn when they become independent from their mothers.[91]

Males live four years less than the females, whose maximum longevity is about 17 years. Females with a normal body size and who have had sufficient summer nutrition can begin breeding anytime between the ages of one to three years.[90] When a female has undergone nutritional stress, it is possible for her to not reproduce for the year.[92] Dominant males, those with larger body size and antler racks, inseminate more than one doe a season.

Social structure, migration and range

Some populations of North American caribou, for example many herds in the barren-ground caribou subspecies and some woodland caribou in Ungava and Labrador, migrate the farthest of any terrestrial mammal, travelling up to 5,000 km (3,000 mi) a year, and covering 1,000,000 km2 (400,000 sq mi).[2][94] Other North American populations, the boreal woodland caribou for example, are largely sedentary.[95] The European populations are known to have shorter migrations. Island herds such as the subspecies R. t. pearsoni and R. t. platyrhynchus make local movements. Migrating reindeer can be negatively affected by parasite loads. Severely infected individuals are weak and probably have shortened lifespans, but parasite levels vary between populations. Infections create an effect known as culling: infected migrating animals are less likely to complete the migration.[96]

Normally travelling about 19–55 km (12–34 mi) a day while migrating, the caribou can run at speeds of 60–80 km/h (37–50 mph).[2] Young caribou can already outrun an Olympic sprinter when only a day old.[97] During the spring migration smaller herds will group together to form larger herds of 50,000 to 500,000 animals, but during autumn migrations the groups become smaller and the reindeer begin to mate. During winter, reindeer travel to forested areas to forage under the snow. By spring, groups leave their winter grounds to go to the calving grounds. A reindeer can swim easily and quickly, normally at about 6.5 km/h (4 mph) but, if necessary, at 10 km/h (6 mph) and migrating herds will not hesitate to swim across a large lake or broad river.[2]

As an adaptation to their Arctic environment, they have lost their circadian rhythm.[98]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Originally, the reindeer was found in Scandinavia, eastern Europe, Greenland, Russia, Mongolia and northern China north of the 50th latitude. In North America, it was found in Canada, Alaska, and the northern conterminous USA from Washington to Maine. In the 19th century, it was apparently still present in southern Idaho.[2] Even in historical times, it probably occurred naturally in Ireland. During the late Pleistocene era, reindeer occurred as far south as Nevada and Tennessee in North America and as far south as Spain in Europe.[93][99] Today, wild reindeer have disappeared from these areas, especially from the southern parts, where it vanished almost everywhere. Large populations of wild reindeer are still found in Norway, Finland, Siberia, Greenland, Alaska and Canada.

According to the Grubb (2005), Rangifer tarandus is "circumboreal in the tundra and taiga" from "Svalbard, Norway, Finland, Russia, Alaska (USA) and Canada including most Arctic islands, and Greenland, south to northern Mongolia, China (Inner Mongolia; now only domesticated or feral?), Sakhalin Island, and USA (Northern Idaho and the Great Lakes region). Reindeer were introduced to, and feral in, Iceland, Kerguelen Islands, South Georgia Island, Pribilof Islands, St. Matthew Island."[9]

There is strong regional variation in Rangifer herd size. There are large population differences among individual herds and the size of individual herds has varied greatly since 1970. The largest of all herds (in Taimyr, Russia) has varied between 400,000 and 1,000,000; the second largest herd (at the George River in Canada) has varied between 28,000 and 385,000.

While Rangifer is a widespread and numerous genus in the northern Holarctic, being present in both tundra and taiga (boreal forest),[93] by 2013, many herds had "unusually low numbers" and their winter ranges in particular were smaller than they used to be.[4] Caribou and reindeer numbers have fluctuated historically, but many herds are in decline across their range.[100] This global decline is linked to climate change for northern migratory herds and industrial disturbance of habitat for non-migratory herds.[101] Barren-ground caribou are susceptible to the effects of climate change due to a mismatch in the phenological process, between the availability of food during the calving period.[102][103][104]

In November 2016, it was reported that more than 81,000 reindeer in Russia had died as a result of climate change. Longer autumns leading to increased amounts of freezing rain created a few inches of ice over lichen, starving many reindeer.[105]

Diet

Reindeer are ruminants, having a four-chambered stomach. They mainly eat lichens in winter, especially reindeer lichen – a unique adaptation among mammals – they are the only large mammal able to metabolise lichen owing to specialised bacteria and protozoa in their gut.[106] They are the only animals (except for some gastropods) in which the enzyme lichenase, which breaks down lichenin to glucose, has been found.[107] However, they also eat the leaves of willows and birches, as well as sedges and grasses.

They have been known to eat their own fallen antlers, probably for calcium. There is also some evidence to suggest that on occasion, especially in the spring when they are nutritionally stressed,[108] they will feed on small rodents (such as lemmings),[109] fish (such as Arctic char), and bird eggs.[110] Reindeer herded by the Chukchis have been known to devour mushrooms enthusiastically in late summer.[111]

During the Arctic summer, when there is continuous daylight, reindeer change their sleeping pattern from one synchronised with the sun to an ultradian pattern in which they sleep when they need to digest food.[112]

Predators

A variety of predators prey heavily on reindeer, including overhunting by people in some areas, which contributes to the decline of populations.[64]

Golden eagles prey on calves and are the most prolific hunter on the calving grounds.[113] Wolverines will take newborn calves or birthing cows, as well as (less commonly) infirm adults.

Brown bears and polar bears prey on reindeer of all ages, but like the wolverines they are most likely to attack weaker animals, such as calves and sick reindeer, since healthy adult reindeer can usually outpace a bear. The grey wolf is the most effective natural predator of adult reindeer and sometimes takes large numbers, especially during the winter. Some wolf packs as well as individual grizzly bears in Canada may follow and live off of a particular reindeer herd year round.[114][115]

Additionally, as carrion, reindeer may be scavenged opportunistically by foxes, hawks and ravens.

Bloodsucking insects, such as mosquitoes (Culicidae), black flies (Simuliidae), and botflies and deer botflies (Oestridae, specifically, the reindeer warble fly (Hypoderma tarandi) and the reindeer nose botfly (Cephenemyia trompe)), are a plague to reindeer during the summer and can cause enough stress to inhibit feeding and calving behaviours.[116] An adult reindeer will lose perhaps about 1 liter (about 2 US pints) of blood to biting insects for every week it spends in the tundra.[97] The population numbers of some of these predators is influenced by the migration of reindeer. Tormenting insects keep caribou on the move searching for windy areas like hilltops and mountain ridges, rock reefs, lakeshore and forest openings, or snow patches that offer respite from the buzzing horde. Gathering in large herds is another strategy that caribou use to block insects.[117]

In one case, the entire body of a reindeer was found in the stomach of a Greenland shark, a species found in the far northern Atlantic, although this was possibly a case of scavenging, considering the dissimilarity of habitats between the ungulate and the large, slow-moving fish.[118]

Other threats

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) commonly carry meningeal worm or brainworm, a nematode parasite that causes reindeer, moose (Alces alces), elk (Cervus canadensis), and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) to develop fatal neurological symptoms[119][120][121] which include a loss of fear of humans. White-tailed deer that carry this worm are partly immune to it.[79]

Changes in climate and habitat beginning in the twentieth century have expanded range overlap between white-tailed deer and caribou, increasing the frequency of infection within the reindeer population. This increase in infection is a concern for wildlife managers. Human activities, such as "clear-cutting forestry practices, forest fires, and the clearing for agriculture, roadways, railways, and power lines," favour the conversion of habitats into the preferred habitat of the white-tailed deer-"open forest interspersed with meadows, clearings, grasslands, and riparian flatlands."[79]

Conservation

Current status

While overall widespread and numerous, some subspecies are rare and at least one has already gone extinct.[10][11] As of 2015, the IUCN has classified the reindeer as Vulnerable due to an observed population decline of 40% over the last ≈25 years.[2] According to IUCN, Rangifer tarandus as a species is not endangered because of its overall large population and its widespread range.[2]

In North America, R. t. dawsoni is extinct,[122][11][10] R. t. pearyi is endangered, R. t. caribou is designated as threatened and some individual populations are endangered. While the subspecies R. t. granti and R. t. groenlandicus are not designated as threatened, many individual herds—including some of the largest—are declining and there is much concern at the local level.[123]

Rangifer tarandus is "endangered in Canada in regions such as south-east British Columbia at the Canadian-USA border, along the Columbia, Kootenay and Kootenai rivers and around Kootenay Lake. Rangifer tarandus is endangered in the United States in Idaho and Washington.

There is strong regional variation in Rangifer herd size, By 2013 many caribou herds in North America had "unusually low numbers" and their winter ranges in particular were smaller than they used to be.[123] Caribou numbers have fluctuated historically, but many herds are in decline across their range.[124] There are many factors contributing to the decline in numbers.[125]

Boreal woodland caribou (COSEWIC designation as threatened)

Ongoing human development of their habitat has caused populations of woodland caribou to disappear from their original southern range. In particular, caribou were extirpated in many areas of eastern North America in the beginning of the 20th century. Woodland caribou were designated as threatened in 2002.[13] Environment Canada reported in 2011 that there were approximately 34,000 boreal woodland caribou in 51 ranges remaining in Canada (Environment Canada, 2011b).[14] Professor Marco Musiani of the University of Calgary said in a statement that "The woodland caribou is already an endangered species in southern Canada and the United States....[The] warming of the planet means the disappearance of their critical habitat in these regions. Caribou need undisturbed lichen-rich environments and these types of habitats are disappearing."[126]

Woodland caribou have disappeared from most of their original southern range and were designated as threatened in 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, (COSEWIC).[13] Environment Canada reported in 2011 that there were approximately 34 000 boreal woodland caribou in 51 ranges remaining in Canada.(Environment Canada, 2011b).[14] "According to Geist, the "woodland caribou is highly endangered throughout its distribution right into Ontario."[9]

In 2002 the Atlantic-Gaspésie population of the woodland caribou was designated as endangered by COSEWIC. The small isolated population of 200 animals was at risk from predation and habitat loss.

Peary caribou (COSEWIC designation as endangered)

In 1991 COSEWIC assigned "endangered status" to the Banks Island and High Arctic populations of Peary caribou. The Low Arctic population of Peary caribou was designated as threatened. By 2004 all three were designated as "endangered."[122]

Numbers have declined by about 72% over the last three generations, mostly because of catastrophic die-off likely related to severe icing episodes. The ice covers the vegetation and caribou starve. Voluntary restrictions on hunting by local people are in place, but have not stopped population declines. Because of the continuing decline and expected changes in long-term weather patterns, this subspecies is at imminent risk of extinction.

— [122]

Relationship with humans

The reindeer has an important economic role for all circumpolar peoples, including the Saami, the Nenets, the Khants, the Evenks, the Yukaghirs, the Chukchi and the Koryaks in Eurasia. It is believed that domestication started between the Bronze and Iron Ages. Siberian reindeer owners also use the reindeer to ride on (Siberian reindeer are larger than their Scandinavian relatives). For breeders, a single owner may own hundreds or even thousands of animals. The numbers of Russian reindeer herders have been drastically reduced since the fall of the Soviet Union. The sale of fur and meat is an important source of income. Reindeer were introduced into Alaska near the end of the 19th century; they interbred with the native caribou subspecies there. Reindeer herders on the Seward Peninsula have experienced significant losses to their herds from animals (such as wolves) following the wild caribou during their migrations.

Reindeer meat is popular in the Scandinavian countries. Reindeer meatballs are sold canned. Sautéed reindeer is the best-known dish in Sápmi. In Alaska and Finland, reindeer sausage is sold in supermarkets and grocery stores. Reindeer meat is very tender and lean. It can be prepared fresh, but also dried, salted and hot- and cold-smoked. In addition to meat, almost all of the internal organs of reindeer can be eaten, some being traditional dishes.[127] Furthermore, Lapin Poron liha, fresh reindeer meat completely produced and packed in Finnish Sápmi, is protected in Europe with PDO classification.[128][129]

Reindeer antlers are powdered and sold as an aphrodisiac, or as an nutritional or medicinal supplement, to Asian markets.

The blood of the caribou was supposedly mixed with alcohol as drink by hunters and loggers in colonial Quebec to counter the cold. This drink is now enjoyed without the blood as a wine and whiskey drink known as Caribou.[130][131]

Reindeer and indigenous peoples

Wild reindeer are still hunted in Greenland and in North America. In the traditional lifestyle of the Inuit people, the Northern First Nations people, the Alaska Natives, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, reindeer is an important source of food, clothing, shelter and tools.

.jpg)

The Caribou Inuit are inland-dwelling Inuit in present-day Nunavut's Keewatin Region, Canada, now known as the Kivalliq Region. They subsisted on caribou year-round, eating dried caribou meat in the winter. The Ihalmiut are caribou Inuit that followed the Qamanirjuaq barren-ground caribou herd.[132]

There is an Inuit saying in the Kivalliq Region:[106]

The caribou feeds the wolf, but it is the wolf who keeps the caribou strong.

— Kivalliq region

Elder Chief of Koyukuk and chair for the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group Benedict Jones, or K’ughto’oodenool’o’, represents the Middle Yukon River, Alaska. His grandmother was a member of the Caribou Clan, who travelled with the caribou as a means to survive. In 1939, they were living the traditional life style at one of their hunting camps in Koyukuk near the location of what is now the Koyukuk National Wildlife Refuge. His grandmother made a pair of new mukluks in one day. K’ughto’oodenool’o’ recounted a story told by an elder, who "worked on the steamboats during the gold rush days out on the Yukon." In late August the caribou migrated from the Alaska Range up north to Huslia, Koyukuk and the Tanana area. One year when the steamboat was unable to continue they ran into a caribou herd numbering estimated at a million animals, migrating across Yukon. "They tied up for seven days waiting for the caribou to cross. They ran out of wood for the steamboats, and had to go back down 40 miles to the wood pile to pick up some more wood. On the tenth day, they came back and they said there was still caribou going across the river night and day."[29]

The Gwich'in, the indigenous people of northwestern Canada and northeastern Alaska, have been dependent on the international migratory Porcupine caribou herd for millennia.[133]:142 To them caribou—vadzaih—is the cultural symbol and a keystone subsistence species of the Gwich'in, just as the buffalo is to the Plains Indians.[134] Innovative language revitalisation projects are underway to document the language and to enhance the writing and translation skills of younger Gwich'in speakers. In one project lead research associate and fluent speaker Gwich’in elder Kenneth Frank works with linguists which include young Gwich'in speakers affiliated with the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks to document traditional knowledge of caribou anatomy. The main goal of the research, was to "elicit not only what the Gwich'in know about caribou anatomy, but how they see caribou and what they say and believe about caribou that defines themselves, their dietary and nutritional needs, and their subsistence way of life."[134] Elders have identified at least 150 descriptive Gwich'in names for all of the bones, organs and tissues. Associated with the caribou's anatomy are not just descriptive Gwich'in names for all of the body parts including bones, organs, and tissues, but also "an encyclopedia of stories, songs, games, toys, ceremonies, traditional tools, skin clothing, personal names and surnames, and a highly developed ethnic cuisine."[134]

In the 1980s, Gwich'in Traditional Management Practices were established to protect the Porcupine caribou, upon which the Gwich'in people depend. They "codified traditional principles of caribou management into tribal law" which include "limits on the harvest of caribou and procedures to be followed in processing and transporting caribou meat" and limits on the number of caribou to be taken per hunting trip.[135]

Reindeer husbandry

The reindeer is the only domesticated deer in the world, though it may be more accurate to consider reindeer as semi-domesticated. Reindeer in northern Fennoscandia (northern Norway, Sweden and Finland) as well in the Kola Peninsula and Yakutia in Russia, are all semi-wild domestic reindeer (Rangifer tarandus f. domesticus), ear-marked by their owners. Some reindeer in the area are truly domesticated, mostly used as draught animals (nowadays commonly for tourist entertainment and races, traditionally important for the nomadic Sámi). Domesticated reindeer have also been used for milk, e.g. in Norway.

There are only two genetically pure populations of wild reindeer in Northern Europe: wild mountain reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) that live in central Norway, with a population in 2007 of between 6,000 and 8,400 animals;[136] and wild Finnish forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus fennicus) that live in central and eastern Finland and in Russian Karelia, with a population of about 4,350, plus 1,500 in Arkhangelsk and 2,500 in Komi.[137]

DNA analysis indicates that reindeer were independently domesticated in Fennoscandia and Western Russia (and possibly Eastern Russia).[138] Reindeer have been herded for centuries by several Arctic and sub-Arctic peoples, including the Sami, the Nenets and the Yakuts. They are raised for their meat, hides and antlers and, to a lesser extent, for milk and transportation. Reindeer are not considered fully domesticated, as they generally roam free on pasture grounds. In traditional nomadic herding, reindeer herders migrate with their herds between coastal and inland areas according to an annual migration route and herds are keenly tended. However, reindeer were not bred in captivity, though they were tamed for milking as well as for use as draught animals or beasts of burden. Domesticated reindeer are shorter-legged and heavier than their wild counterparts.

The use of reindeer for transportation is common among the nomadic peoples of northern Russia (but not anymore in Scandinavia). Although a sled drawn by 20 reindeer will cover no more than 20–25 km a day (compared to 7–10 km on foot, 70–80 km by a dog sled loaded with cargo and 150–180 km by a dog sled without cargo), it has the advantage that the reindeer will discover their own food, while a pack of 5–7 sled dogs requires 10–14 kg of fresh fish a day.[139]

The use of reindeer as semi-domesticated livestock in Alaska was introduced in the late 19th century by the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, with assistance from Sheldon Jackson, as a means of providing a livelihood for Native peoples there.[140] Reindeer were imported first from Siberia and later also from Norway. A regular mail run in Wales, Alaska, used a sleigh drawn by reindeer.[141] In Alaska, reindeer herders use satellite telemetry to track their herds, using online maps and databases to chart the herd's progress.

Domesticated reindeer are mostly found in northern Fennoscandia and Russia, with a herd of approximately 150–170 reindeer living around the Cairngorms region in Scotland. The last remaining wild tundra reindeer in Europe are found in portions of southern Norway.[142] The International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry (ICR), a circumpolar organisation, was established in 2005 by the Norwegian government. ICR represents over 20 indigenous reindeer peoples and about 100,000 reindeer herders in 9 different national states.[143] In Finland, there are about 6,000 reindeer herders, most of whom keep small herds of less than 50 reindeer to raise additional income. With 185,000 reindeer (2001), the industry produces 2,000 tons of reindeer meat and generates 35 million euros annually. 70% of the meat is sold to slaughterhouses. Reindeer herders are eligible for national and EU agricultural subsidies, which constituted 15% of their income. Reindeer herding is of central importance for the local economies of small communities in sparsely populated rural Sápmi.[144]

Currently, many reindeer herders are heavily dependent on diesel fuel to provide for electric generators and snowmobile transportation, although solar photovoltaic systems can be used to reduce diesel dependency.[145]

In history

Reindeer hunting by humans has a very long history and wild reindeer "may well be the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting."[15]

Both Aristotle and Theophrastus have short accounts – probably based on the same source – of an ox-sized deer species, named tarandos, living in the land of the Bodines in Scythia, which was able to change the colour of its fur to obtain camouflage. The latter is probably a misunderstanding of the seasonal change in reindeer fur colour. The descriptions have been interpreted as being of reindeer living in the southern Ural Mountains in c. 350 BC[20]

A deer-like animal described by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (chapter 6.26) from the Hercynian Forest in the year 53 BC is most certainly to be interpreted as reindeer:[20][146]

There is an ox shaped like a stag. In the middle of its forehead a single horn grows between its ears, taller and straighter than the animal horns with which we are familiar. At the top this horn spreads out like the palm of a hand or the branches of a tree. The females are of the same form as the males, and their horns are the same shape and size.

According to Olaus Magnus's Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus – printed in Rome in 1555 – Gustav I of Sweden sent 10 reindeer to Albert I, Duke of Prussia, in the year 1533. It may be these animals that Conrad Gessner had seen or heard of.

During World War II, the Soviet Army used reindeer as pack animals to transport food, ammunition and post from Murmansk to the Karelian front and bring wounded soldiers, pilots and equipment back to the base. About 6,000 reindeer and more than 1,000 reindeer herders were part of the operation. Most herders were Nenets, who were mobilised from the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, but reindeer herders from Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Komi also participated.[147][148]

Santa Claus's reindeer

Around the world, public interest in reindeer peaks in the Christmas period.[149] According to folklore, Santa Claus's sleigh is pulled by flying reindeer. These were first named in the 1823 poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas", where they are called Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder, and Blixem.[150] Dunder was later changed to Donder and—in other works—Donner (in German, "thunder") and Blixem was later changed to Bliksem, then Blitzen (blitz being German for "lightning"). Some consider Rudolph as part of the group as well, though he was not part of the original named work referenced previously. Rudolph was added by Robert L. May in 1939 in his book Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.[151]

In mythology and art

Among the Inuit, there is a story of the origin of the caribou,[152]

Once upon a time there were no caribou on the earth. But there was a man who wished for caribou, and he cut a hole deep in the ground, and up this hole came caribou, many caribou. The caribou came pouring out, until the earth was almost covered with them. And when the man thought there were caribou enough for mankind, he closed up the hole again. Thus the caribou came up on earth.

— [152]

Inuit artists from the barren lands, incorporate depictions of caribou—and items made from caribou antlers and skin—in carvings, drawings, prints and sculpture.

Contemporary Canadian artist Brian Jungen's, of Dunne-za First Nations ancestry, commissioned an installation entitled "The ghosts on top of my head" (2010–11) in Banff, Alberta, which depicts the antlers of caribou, elk and moose.[153]

I remember a story my Uncle Jack told me – a Dunne-Za creation story about how animals once ruled the earth and were ten times their size and that got me thinking about scale and using the idea of the antler, which is a thing that everyone is scared of, and making it into something more approachable and abstract.

— Brian Jungen 2011[153]

Tomson Highway, CM[154] is a Canadian and Cree playwright, novelist, and children's author, who was born in a remote area north of Brochet, Manitoba.[154] His father, Joe Highway, was a caribou hunter. His 2001 children's book entitled Caribou Song/atíhko níkamon was selected as one of the "Top 10 Children’s Books" by the Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail. The young protagonists of Caribou Song, like Tomson himself, followed the caribou herd with their families.

Heraldry and symbols

Several Norwegian municipalities have one or more reindeer depicted in their coats-of-arms: Eidfjord, Porsanger, Rendalen, Tromsø, Vadsø and Vågå. The historic province of Västerbotten in Sweden has a reindeer in its coat of arms. The present Västerbotten County has very different borders and uses the reindeer combined with other symbols in its coat-of-arms. The city of Piteå also has a reindeer. The logo for Umeå University features three reindeer.[155]

The Canadian 25-cent coin, or "quarter" features a depiction of a caribou on one face. The caribou is the official provincial animal of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, and appears on the coat of arms of Nunavut. A caribou statue was erected at the centre of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial, marking the spot in France where hundreds of soldiers from Newfoundland were killed and wounded in World War I and there is a replica in Bowring Park in St. John's, Newfoundland's capital city.

Two municipalities in Finland have reindeer motifs in their coats-of-arms: Kuusamo[156] has a running reindeer and Inari[157] has a fish with reindeer antlers.

See also

Notes

- The Integrated Taxonomic Information System list Wilson and Geist on their experts panel.

- Banfield rejected this classification in 1961. However, Geist and others considered it valid.

- The George River and Leaf River caribou herds are classified as woodland caribou, but are also migratory with tundra as their primary range.

- According to Inuit elder, Marie Kilunik of the Aivilingmiut, Canadian Inuit preferred the caribou skins from caribou taken in the late summer of fall when their coats had thickened. They used for winter clothing "because each hair is hollow and fills with air trapping heat."(Marie Kilunik, Aivilingmiut, Crnkovich 1990:116).

References

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Transaction Publishers. pp. 170–177. ISBN 978-1-4128-4514-4. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Gunn, A. (2016). "Rangifer tarandus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T29742A22167140. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016.

- Flagstad, Oystein; Roed, Knut H (2003). "Refugial origins of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences" (PDF). Evolution. 57 (3): 658–670. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2003)057[0658:roorrt]2.0.co;2. PMID 12703955. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Russell, D.E.; Gunn, A. (20 November 2013). "Migratory Tundra Rangifer". NOAA Arctic Research Program. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kolpasсhikov, L.; Makhailov, V.; Russell, D. E. (2015). "The role of harvest, predators, and socio-political environment in the dynamics of the Taimyr wild reindeer herd with some lessons for North America" (PDF). Ecology and Society. 20. doi:10.5751/ES-07129-200109.

- "Tradition 'snatched away': Labrador Inuit struggle with caribou hunting ban | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Robbins, Jim (14 April 2018). "Gray Ghosts, the Last Caribou in the Lower 48 States, Are 'Functionally Extinct'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Eder, Tamara; Kennedy, Gregory (2011), Mammals of Canada, Edmonton, Alberta: Lone Pine, p. 81, ISBN 978-1-55105-857-3

- Grubb, Peter (2005), Rangifer tarandus, Smithsonian: National Museum of Natural History, archived from the original on 16 January 2014, retrieved 15 January 2014

- Peter Gravlund; Morten Meldgaard; Svante Pääbo & Peter Arctander (1998). "Polyphyletic Origin of the Small-Bodied, High-Arctic Subspecies of Tundra Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 10 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1006/mpev.1998.0525. PMID 9878226.

- S. A. Byun; B. F. Koop; T. E. Reimchen (2002). "Evolution of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni)". Can. J. Zool. 80 (5): 956–960. doi:10.1139/z02-062.

- "Population Critical: How are Caribou Faring?" (PDF). Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and The David Suzuki Foundation. December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "Designatable Units for Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in Canada" (PDF), COSEWIC, Ottawa, Ontario: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, p. 88, 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016, retrieved 18 December 2013

- "Evaluation of Programs and Activities in Support of the Species at Risk Act" (PDF), Environment Canada, pp. 2, 9, 24 September 2012, archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2013, retrieved 27 December 2013

- "In North America and Eurasia the species has long been an important resource—in many areas the most important resource—for peoples inhabiting the northern boreal forest and tundra regions." (Banfield 1961:170; Kurtén 1968:170)Ernest S. Burch, Jr. (1972). "The Caribou/Wild Reindeer as a Human Resource". American Antiquity. 37 (3): 339–368. doi:10.2307/278435. JSTOR 278435.

- Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, 1971

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast

- "The Sámi and their reindeer". Austin, Texas: University of Texas. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Schaefer, J. A.; Mahoney, S. P. (2001). "Antlers on female caribou: biogeography of the bones of contention". Ecology. 82 (12): 3556–3560. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[3556:aofcbo]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 2680172.

- Sarauw, Georg (1914). "Das Rentier in Europa zu den Zeiten Alexanders und Cæsars" [The reindeer in Europe to the times of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar]. In Jungersen, H. F. E.; Warming, E. (eds.). Mindeskrift i Anledning af Hundredeaaret for Japetus Steenstrups Fødsel (in German). Copenhagen. pp. 1–33.

- Gesner, K. (1617) Historia animalium. Liber 1, De quadrupedibus viviparis. Tiguri 1551. p. 156: De Tarando. 9. 950: De Rangifero.

- Aldrovandi, U. (1621) Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia. Bononiæ. Cap. 30: De Tarando– Cap. 31: De Rangifero.

- "deer". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. Archived from the original on 25 March 2004.

- Flexner, Stuart Berg and Leonore Crary Hauck, eds. (1987). The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, 2nd ed. (unabridged). New York: Random House, pp. 315–16

- Spalding, Alex, Inuktitut – A Multi-Dialectal Outline Dictionary (with an Aivilingmiutaq base). Nunavut Arctic College, Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada, 1998.

- Eskimoisches Wörterbuch, gesammelt von den Missionaren in Labrador, revidirt und herausgegeben von Friedrich Erdmann. Budissin [mod. Bautzen] 1864.

- Iñupiat Eskimo dictionary Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Alaska State Library, Donald H. Webster & Wilfried Zibell, 1970. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Vuntut Gwich'in", First Voices, 2001–2013, retrieved 17 January 2014

- "Caribou Census Complete: 325,000 animals" (PDF), Caribou Trails: News from the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group, Nome, Alaska: Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, August 2012, archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2012, retrieved 14 January 2014

- "FirstVoices: Hän: words".

- Bennett, John (1 June 2008), Uqalurait: An Oral History of Nunavut, McGill-Queen's Native and Northern Series, McGill-Queen's University Press, p. 63

- "Álgu-tietokanta". kaino.kotus.fi. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Banfield, Alexander William Francis (1961). "A Revision of the Reindeer and Caribou, Genus Rangifer". Bulletin of the National Museum of Canada. Biological Services. 177 (66).

- Geist, V. (2007). "Defining subspecies, invalid taxonomic tools, and the fate of the woodland caribou". Rangifer. 27 (4): 25. doi:10.7557/2.27.4.315.

- Grubb, P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Rangifer tarandus caribou (Gmelin, 1788): Taxonomic Serial No.: 202411", Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), 18 December 2013, archived from the original on 19 December 2013, retrieved 18 December 2013

- Cronin, M. A.; MacNeil, M. D.; Patton, J. C. (2005). "Variation in Mitochondrial Dna and Microsatellite Dna in Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 86 (3): 495–505. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[495:VIMDAM]2.0.CO;2.

- Mallory, F. F.; Hillis, T. L. (1998). "Demographic characteristics of circumpolar caribou populations: Ecotypes, ecological constraints, releases, and population dynamics". Rangifer. 18 (5): 49. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.2188. doi:10.7557/2.18.5.1541.

- COSEWIC, p. 3

- COSEWIC, p. 10

- Mattioli, S. (2011). Caribou (Rangifer tarandus). pp. 431–432 in: Handbook of the Mammals of the World, vol. 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4

- "The Holocene occurrence of reindeer on Franz Josef Land, Russia | Request PDF". ResearchGate. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Reindeer In Iceland". Tinna Adventure. 13 February 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Geist, Valerius (1998), Deer of the world: their evolution, behavior, and ecology, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, ISBN 9780811704960

- Bergerud, A. T. (1996). "Evolving perspectives on caribou population dynamics, have we got it right yet?". Rangifer. 16 (4): 95. doi:10.7557/2.16.4.1225.

- Festa-Bianchet, M.; Ray, J.C.; Boutin, S.; Côté, S.D.; Gunn, A.; et al. (2011). "Conservation of Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in Canada: An Uncertain Future". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 89 (5): 419–434. doi:10.1139/z11-025.

- Mager, Karen H. (2012). "Population Structure and Hybridization of Alaskan Caribou and Reindeer: Integrating Genetics and Local Knowledge" (PDF). Fairbanks, Alaska: PhD dissertation, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- New World Deer (Capriolinae). Answers.com

- Lin, Zeshan (2019). "Biological adaptations in the Arctic cervid, the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus)". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aav6312.

- Nasoori, Alireza (2020). "Formation, structure, and function of extra‐skeletal bones in mammals". Biological Reviews. doi:10.1111/brv.12597.

- Reid, F. (2006). Mammals of North America. Peterson Field Guides. ISBN 978-0-395-93596-5

- Smith, B.E. (1998), "Antler size and winter mortality of elk: effects of environment, birth year, and parasites", Journal of Mammalogy, 79 (3): 1038–1044, doi:10.2307/1383113, JSTOR 1383113

- Mahoney, Shane P.; Weir, Jackie N.; Luther, J. Glenn; Schaefer, James A.; Morrison, Shawn F. (2011), "Morphological change in Newfoundland caribou: Effects of abundance and climate", Rangifer, 31 (1): 21–34, doi:10.7557/2.31.1.1917, archived from the original on 3 November 2014

- Mahoney, Shane P.; Weir, Jackie N.; Luther, J. Glenn; Schaefer, James A.; Morrison, Shawn F. (2011), "Morphological change in Newfoundland caribou: Effects of abundance and climate", Rangifer, 31 (1): 24, doi:10.7557/2.31.1.1917, archived from the original on 3 November 2014

- Markusson, Eystein; Folstad, Ivar (1 May 1997). "Reindeer antlers: visual indicators of individual quality?". Oecologia. 110 (4): 501–507. Bibcode:1997Oecol.110..501M. doi:10.1007/s004420050186. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28307241.

- Thomas, Don; Barry, Sam (2005). "Antler Mass of Barren-Ground Caribou Relative to Body Condition and Pregnancy Rate". Arctic. 58 (3): 241–246. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.541.4295. JSTOR 40512709.

- Geist, Valerius (2007), "Defining subspecies, invalid taxonomic tools, and the fate of the woodland caribou", Rangifer, The Eleventh North American Caribou Workshop (2006), 27 (Special Issue 17): 25–28, doi:10.7557/2.27.4.315, archived from the original on 4 October 2015, retrieved 17 December 2013

- "Caribou", Virtual Wildlife, Lethbridge, Alberta, archived from the original on 3 November 2014

- GNWT, Species at Risk in the Northwest Territories 2012 (PDF), Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, ISBN 978-0-7708-0196-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015, retrieved 31 October 2014

- Gunn, Anne; Nishi, J. (1998), "Review of information for Dolphin and Union caribou herd", in Gunn, A.; Seal, U.S.; Miller, P.S. (eds.), Population and Habitat Viability Assessment Workshop for the Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi), Briefing book, Apple Valley, Minnesota: Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/UCN), pp. 1–22

- "Tuktu — Caribou", Canada's Arctic, Guelph, Ontario, 2002a, archived from the original on 15 November 2014, retrieved 17 January 2014

- Woodland caribou. 2000.

- Hebert PDN; Wearing-Wilde J, eds. (2002), Tuktu — Caribou, Canada's Polar Life (CPL), University of Guelph, archived from the original on 20 October 2017, retrieved 30 October 2017,

"Since 1986, elders in the community have worked ...the Igloolik Research Centre ...to record their knowledge for posterity on paper and audio tape..Noah Piugaattuk contributed 70 to 80 hours of audio tape." Use of antlers (IOHP 037);

- Woodland caribou boreal population – biology, SARA, October 2014, retrieved 3 November 2014

- Richler, Noah (29 May 2007). This Is My Country, What's Yours?: A Literary Atlas of Canada. Random House. p. 496. ISBN 9781551994178.

- Interview 065, Igloolik Oral History Project (IOHP), Igloolik, Nunavut, 1991

- Thing, Henning; Olesen, Carsten Riis; Aastrup, Peter (1986), "Antler possession by west Greenland female caribou in relation to population characteristics", Rangifer, 6 (2): 297, doi:10.7557/2.6.2.662

- McKibbon, Sean (21 January 2000). "Igloolik elders win northern science award". Nunatsiaq News. Igloolik. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

Elders in Igloolik were recognized with a national science award last week for their efforts in preserving traditional Inuit knowledge.

- Oopakak, National Gallery of Canada, n.d., archived from the original on 12 October 2015, retrieved 31 October 2017

- Bennett, John (1 June 2008), Uqalurait: An Oral History of Nunavut, McGill-Queen's Native and Northern Series, McGill-Queen's University Press, p. 116

- Moote, I. (1955), "The thermal insulation of caribou pelts", Textile Research Journal, 25 (10): 832–837, doi:10.1177/004051755502501002

- Dugmore, Arthur Radclyffe (1913), The romance of the Newfoundland caribou, Philadelphia: Lippincott, p. 191, retrieved 2 November 2014

- "Two Missense Mutations in Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Are Strongly Associated With Dark Ventral Coat Color in Reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus)". doi:10.1111/age.12187. hdl:2164/4960. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rahiman, Mohd Hezri Fazalul (2009), Heat exchanger (PDF), Malaysia, archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2013, retrieved 3 November 2014

- Blix, A.S.; Johnsen, Helge Kreiitzer (1983), "Aspects of nasal heat exchange in resting reindeer", Journal of Physiology, 340: 445–454, doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014772, PMC 1199219, PMID 6887057

- "In the winter, the fleshy pads on these toes grow longer and form a tough, hornlike rim. Caribou use these large, sharp-edged hooves to dig through the snow and uncover the lichens that sustain them in winter months. Biologists call this activity "cratering" because of the crater-like cavity the caribou’s hooves leave in the snow."All About Caribou Archived 6 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Project Caribou

- Image of reindeer cratering in snow Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Arcticphoto.co.uk. Retrieved on 16 September 2011.

- Caribou at the Alaska Department of Fish & Game Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Adfg.state.ak.us. Retrieved on 16 September 2011.

- Naughton, Donna (2011), The Natural History of Canadian Mammals, Canadian Museum of Nature and University of Toronto Press, pp. 543, 562, 567, ISBN 978-1-4426-4483-0

- Aanes, R. (2007).Svalbard reindeer. Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Shackleton, David (May 2013) [1999], Hoofed Mammals of British Columbia, ISBN 978-0-7726-6638-3

- Banfield, Alexander William Francis (1966), "The caribou", in Smith, I.N. (ed.), The Unbelievable Land, Ottawa: Queen's Press, pp. 25–28

- Reindeer use UV light to survive in the wild Archived 29 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Ucl.ac.uk (26 May 2011). Retrieved on 16 September 2011.

- Stokken, Karl-Arne; Folkow, Lars (December 2013). "Shifting mirrors: adaptive changes in retinal reflections to winter darkness in Arctic reindeer". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 280 (1773): 20132451. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2451. PMC 3826237. PMID 24174115.

- Karasov, W.H. and Martinez del Rio, C. 2007. The Chemistry and Biology of Food in Physiological Ecology: How Animals Process Energy, Nutrients, and Toxins (pp. 49–108).