Peary caribou

The Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) is a subspecies of caribou found in the High Arctic islands of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories in Canada. They are the smallest of the North American caribou, with the females weighing an average of 60 kg (130 lb) and the males 110 kg (240 lb). In length the females average 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) and the males 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in).

| Peary caribou | |

|---|---|

| |

| Peary caribou | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Rangifer |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | R. t. pearyi |

| Trinomial name | |

| Rangifer tarandus pearyi (Allen, 1902) | |

| |

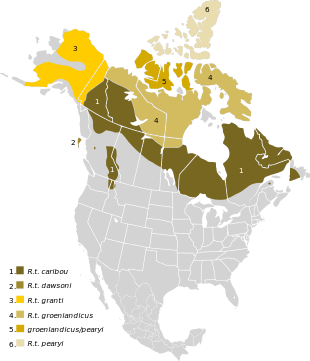

| Approximate range of Peary caribou. Overlap with other subspecies of caribou is possible for contiguous range. 1. Rangifer tarandus caribou, which is subdivided into ecotypes: woodland (boreal), woodland (migratory) and woodland (montane), 2. R. t. dawsoni (extinct 1908), 3. R. t. granti, 4. R. t. groenlandicus, 5. R. t. groenlandicus/pearyi, 6. R. t. pearyi | |

Like other caribou, both the males and females have antlers. The males grow their antlers from March to August and the females from June to September, and in both cases the velvet is gone by October. The coat of the caribou is white and thick in the winter. In the summer it becomes short and darker, almost slate-grey in colour. The coat is made up of hollow hair which helps to trap warmer air and insulate the caribou.

The males become sexually mature after two years and the females after three years. Breeding is in the fall and depends on the female having built up sufficient fat reserves. The gestation period last for seven to eight months and one calf is produced.

Peary caribou feed on most of the available grasses, Cyperaceae (sedges), lichen and mushrooms. In particular they seem to enjoy the purple saxifrage and in summer their muzzles become purple from the plants. Their hooves are sharp and shaped like a shovel to enable them to dig through the snow in search of food.

The caribou rarely travel more than 150 km (93 mi) from their winter feeding grounds to the summer ones. They are able to outrun the Arctic wolf, their main predator, and are good swimmers. They usually travel in small groups of no more than twelve in the summer and four in the winter.

The Peary caribou population has dropped from above 40,000 in 1961 to about 700 in 2009. During this period, the number of days with above freezing temperatures has increased significantly, resulting in ice layers in the snow pack. These ice layers hinder foraging and are the likely cause for dramatic drops in caribou population in the future.

The Peary caribou, called tuktu in Inuinnaqtun/Inuktitut, and written as ᕐᑯᑦᓯᑦᑐᒥ ᑐᒃᑐ in Inuktitut syllabics,[3] is a major food source for the Inuit and was named after the American explorer Robert Peary.

Morphology

Pelage

During the winter, the fur of the Peary caribou becomes thicker and whiter. In the summer it is shorter and darker. The pelage of the Peary caribou is white in winter and slate-grey with white legs and underparts in summer like the barren-ground caribou in the Dolphin-Union caribou herd. The Dolphin-Union caribou are slightly darker.[4]

Like all caribou the hollow hairs help trap warm air and insulate their bodies.

Antlers

The Peary caribou and the Dolphin-Union caribou herd both have light slate-grey antler velvet.[5] The antler velvet of the barren-ground caribou and the boreal woodland caribou are both dark chocolate brown.[4]

Habitat

The Peary caribou migrate seasonally up to 150 km (93 mi) each way. They occupy High Arctic islands, including Banks Island, Prince of Wales Island, Somerset Island and the Queen Elizabeth Islands. In summer they search for the richest vegetation which is found "on the upper slopes of river valleys and uplands."[4] In the winter, they "inhabit areas where the snow is not too deep such as rugged uplands, beach ridges and rocky outcrops."[4]

Aulavik National Park at the northern end of Banks Island is also home to the Peary caribou.[6] The Thomsen River runs through the park and is the northernmost navigable river (by canoe) in North America. Aulavik National Park, a fly-in park, protects about 12,274 km2 (4,739 sq mi) of Arctic lowlands at the northern end of the island.[6] In Inuvialuktun Aulavik means "place where people travel" and caribou have been hunted there for more than 3,400 years, from Pre-Dorset cultures to contemporary Inuvialuit.[6]

The last live caribou reported from northern Greenland were most likely Peary caribou that had strayed from Ellesmere Island. They were last seen in Hall Land in 1922.[7]

Conservation

It was assigned a status of threatened in April 1979.[1] In May 2004 the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) listed the Peary caribou as endangered.

"The original designation considered a single unit that included Peary caribou, Rangifer tarandus pearyi, and what is now known as the Dolphin and Union population of the barren-ground caribou, Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus. Split to allow designation of three separate populations in 1991: Banks Island (Endangered), High Arctic (Endangered) and Low Arctic (Threatened) populations. In May 2004 all three population designations were de-activated, and the Peary Caribou, Rangifer tarandus pearyi, was assessed separately from the Barren-ground Caribou (Dolphin and Union population), Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus. The subspecies pearyi is composed of a portion of the former "Low Arctic population" and all of the former "High Arctic" and "Banks Island" populations."

— COSEWIC 2004:iii

Footnotes

- COSEWIC 2004.

- Anand-Wheeler 2009.

- NWT 2012.

- Gunn & Seal 1998.

- "Aulavik National Park of Canada", Parks Canada, 16 January 2014, retrieved 1 November 2014

- Morten Meldgaard, (1986) The Greenland Caribou - Zoogeography, Taxonomy, and Population Dynamics, ISBN 978-87-635-1180-3 p. 44

References

- Anand-Wheeler, Ingrid (2002), "Terrestrial Mammals of Nunavut", NatureServe, ISBN 1-55325-035-4

- "Population size", BBC, 11 June 2009

- "COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Peary Caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi and Barren-ground Caribou Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus Dolphin and Union population in Canada" (PDF), COSEWIC, May 2004, ISBN 0-662-37375-8, retrieved 1 November 2014 Peary Caribou – Endangered; Barren-Ground Caribou (Dolphin and Union Population) –Special Concern.

- "COSEWIC 2014 assessment and update status report on the Peary caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi and the barren-ground caribou Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus (Dolphin and Union population) in Canada", Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Ottawa, 2014

- "Peary Caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi" (PDF), Government of Nunavut, nd, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2014, retrieved 1 November 2014

- "UNEP/GRID-Arendal Maps and Graphics Library", GRIDA, June 2007, archived from the original on 30 January 2008, retrieved 27 January 2008

|chapter=ignored (help) - Gunn, Anne; Miller, Frank L.; Thomas, D.C. (1979), "COSEWIC status report on the Peary caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi in Canada", Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Ottawa, p. 40

- Gunn, Anne; Nishi, J. (1998), "Review of information for Dolphin and Union caribou herd", in Gunn, A.; Seal, U.S.; Miller, P.S. (eds.), Population and Habitat Viability Assessment Workshop for the Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi), Briefing book, Apple Valley, Minnesota: Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/UCN), pp. 1–22

- Miller, Frank L. (1991), "Update COSEWIC status report on the Peary caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi in Canada", Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Ottawa, p. 124

- GNWT, Species at Risk in the Northwest Territories 2012 (PDF), Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, ISBN 978-0-7708-0196-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015, retrieved 31 October 2014

Further reading

- Larter, Nicholas C, and John A Nagy. 2001. "Variation between Snow Conditions at Peary Caribou and Muskox Feeding Sites and Elsewhere in Foraging Habitats on Banks Island in the Canadian High Arctic". Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 33, no. 2: 123.

- Maher, Andrew Ian. Assessing Snow Cover and Its Relationship to Distribution of Peary Caribou in the High Arctic. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, 2006. ISBN 0-494-05053-5

- Manning, T. H. The Relationship of the Peary and Barren Ground Caribou. Montreal: Arctic Institute of North America, 1960.

- Miller, F. L., E. J. Edmonds, and A. Gunn. Foraging Behaviour of Peary Caribou in Response to Springtime Snow and Ice Conditions. [Ottawa]: Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, 1982. ISBN 0-662-12017-5

- Northwest Territories. (2001). NWT peary caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi. NWT species at risk fact sheets. [Yellowknife]: Northwest Territories Resources, Wildlife and Economic Development.

- Tews, Joerg, Michael A D Ferguson, and Lenore Fahrig. 2007. "Potential Net Effects of Climate Change on High Arctic Peary Caribou: Lessons from a Spatially Explicit Simulation Model". Ecological Modelling. 207, no. 2: 85.

External links

- NWT Peary Caribou; NWT Dolphin-Union Caribou at the Wayback Machine (archived May 5, 2009)