Java mouse-deer

The Java mouse-deer (Tragulus javanicus)[2] is a species of even-toed ungulate in the family Tragulidae. When it reaches maturity it is about the size of a rabbit, making it the smallest living ungulate. It is found in forests in Java and perhaps Bali, although sightings there have not been verified.[1]

| Java mouse-deer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Java mouse-deer at the Jerusalem Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Tragulidae |

| Genus: | Tragulus |

| Species: | T. javanicus |

| Binomial name | |

| Tragulus javanicus (Osbeck, 1765) | |

Taxonomy

The Java mouse-deer's common scientific name is Tragulus javanicus, although other classification names for it exist, including Tragulus javanica, Cervus javanicus, and the heterotypic synonym Tragulus fuscatus.[1][3][4][5] The Java mouse-deer is also known by many common names, including Javan chevrotain, Javan mousdeer, or Java Mousedeer.[6] The taxonomic status of the Java mouse-deer is questionable, but recent craniometric analyses have begun to shed light on the taxonomic discrepancies. Previously, the Java mouse-deer, Tragulus javanicus, was commonly thought to represent the wider class of large chevrotains, but it was found that these, unlike the Java mouse-deer, do not likely reside on Java. Three species groups of Tragulus have been identified based on craniometric skull analyses and coat coloration patterns. These three species groups are Tragulus javanicus, Tragulus napu, and Tragulus versicolor. Based upon these craniometric analyses, Tragulus javanicus was then further separated based on the organisms’ known geographic locations: Tragulus williamsoni (found in northern Thailand and possibly southern China), Tragulus kanchil (found in Borneo, Sumatra, the Thai–Malay Peninsula, islands within the Greater Sunda region, and continental Southeast Asia), and Tragulus javanicus (found in Java).[7] Thus, because of its uniqueness to the island of Java, the Java mouse-deer is now considered a distinct species, although this fact has not significantly affected its current classification.[8]

Appearance and biology

Mouse-deer possess a triangular-shaped head, arched back, and round body with elevated rear quarters. The thin, short legs which support the mouse-deer are about the diameter of an average pencil. Although Java mouse-deer do not possess antlers or horns like regular deer, male Java mouse-deer have elongated, tusk-like upper canines which protrude downward from the upper jaw along the sides of their mouth. Males use these “tusks” to defend themselves and their mates against rivals.[9] Females can be distinguished from males because they lack these prominent canines, and they are slightly smaller than the males.[6] Java mouse-deer can furthermore be distinguished by their lack of upper incisors. The coat coloration of the Java mouse-deer is reddish-brown with a white underside. Pale white spots or vertical markings are also present on the animal's neck.[6]

With an average length of 45 cm (18 in) and an average height of 30 cm (12 in), the Java mouse-deer is the smallest extant (living) ungulate or hoofed mammal, as well as the smallest extant even-toed ungulate.[6][10][11] The weight of the Java mouse-deer ranges from 1 to 2 kilograms (2.2 to 4.4 lb), with males being heavier than females. It has an average tail length of about 5 cm (2.0 in). Mouse-deer are thought to be the most primitive ruminants based on their behaviour and the fossil record, thus they are the living link between ruminants and non-ruminants.[12][11]

The Java mouse-deer is endothermic and homoeothermic, and has an average basal metabolic rate of about 4.883 watts.[6] It also has the smallest red blood cells (erythrocytes) of any mammal, and about 12.8% of the cells have pits on them. The pits range in diameter from 68 to 390 nanometres. Red blood cells with pits are unique and have not been reported before either physiologically or pathologically.[10]

Ecology

Geographic range

Tragulus javanicus is usually considered to be endemic to Java, Indonesia. There have been unverified reports of sightings on Bali.[1]

Habitat

The Java mouse-deer prefers habitats of higher elevations and the tropical forest regions of Java, although it does appear at lower elevations between 400–700 metres (1,300–2,300 ft) above sea level.[6][13] During the day, Java mouse-deer can be seen roaming in crown-gap areas with dense undergrowth of creeping bamboo, through which they make tunnels through the thick vegetation which lead to resting places and feeding areas.[9] At night, the Java mouse-deer moves to higher and drier ridge areas.[6] It has been argued that Java mouse-deer are an “edge” species, favoring areas of dense vegetation along riverbanks.[6] Additionally, Java mouse-deer have been found to be more prevalent in logged areas than in the more mature forests, and their densities tended to decrease proportionately as the logged forests matured.

Behavior

Diet

Java mouse-deer are primarily herbivores, although in captivity they have been observed to eat insects as well as foliage. Their diet consists primarily of that which they find on the ground in the dense vegetation they inhabit, and they prefer the plants of the faster-growing gap species over the closed forest understory species, likely due to the increased richness of secondary protective compounds which the gap species provide.[6] They are often classified as folivores, eating primarily leaves, shrubs, shoots, buds, and fungi, in addition to fruits which have fallen from trees.[6][9] The fruits which Java mouse-deer commonly consume range from 1–5 grams (0.035–0.176 oz), while the seeds range from 0.01–0.5 g (0.00035–0.01764 oz).[6]

Social behavior

Groups of Java mouse-deer are commonly referred to as “herds,” while females are termed “does,” “hinds,” or “cows.” Males are referred to as either “bucks,” “stags,” or “bulls,” and their young are commonly called “fawns,” or “asses”.[9] It was previously believed that Java mouse-deer were nocturnal, but more recent studies have shown that they are neither truly nocturnal nor diurnal, but instead crepuscular, meaning they prefer to be active during the dim light of dawn and dusk.[9] This behavior has been observed in both wild and captive Java mouse-deer.[14] Although Java mouse-deer form monogamous family groups, they are usually shy, solitary animals. They are also usually silent; the only noise they make is a shrill cry when they are frightened.

Male Java mouse-deer are territorial, marking their territory and their mates with secretions from an intermandibular scent gland under their chin.[9] This territorial marking usually includes urinating or defecating to mark their area. To protect themselves and their mates or to defend their territory, mouse-deer slash rivals with their sharp, protruding canine “tusks.” It has also been observed that, when threatened, the Java mouse-deer will beat its hooves quickly against the ground, reaching speeds of up to 7 beats per second, creating a “drum roll” sound.[15] The territories of Tragulus javanicus males and females have been observed to overlap considerably, yet individuals of the same sex do not share their territories.[6] When giving birth, however, females tend to establish a new home range. Female Java mouse-deer have an estimated home range of 4.3 hectares (11 acres), while males inhabit, on average, 5.9 hectares (15 acres). Additionally, male Java mouse-deer, in nature, were observed to travel distances of 519 metres (1,703 ft) daily on average, while females average 574 metres (1,883 ft) daily.[6]

Reproduction

Java mouse-deer are capable of breeding at any time during the year, and this has been observed during captivity.[6][13] However, some sources have observed that the breeding season for the Java mouse-deer in nature occurs from November to December.[16] Additionally, female mouse-deer have the potential to be pregnant throughout most of their adult life, and they are capable of conceiving 85–155 minutes after giving birth.[13] The Java mouse-deer's gestation period usually lasts 4.5 months, or 144 days.[6][13] Typical litters consist of a single fawn, which resembles a miniature adult, although the tusk-like incisors prevalent in males are not visible in the young mouse-deer.[6] The average mass of a newborn fawn is 370 grams (13 oz), and these precocial young are capable of standing within 30 minutes after birth. Fawns are capable of eating solid food within two weeks, yet it takes around 12 weeks to completely wean the fawns.[9] On average, it takes the young, both male and female, 167 days (~5 months) to reach sexual maturity.[17] Mouse-deer have been observed to live up to 14 years in captivity, but their lifespan in nature is still an open question.[6]

Predators

One of the main predators which the Java mouse-deer face is humans. Through the destruction of their habitat, as well as from hunting and trapping the mouse-deer for food, their pelts, and for pets, humans have considerably reduced the Java mouse-deer population. Mouse-deer are particularly vulnerable to being hunted by humans at night because of their tendency to freeze when illuminated by having a spotlight shone on them.[1] Because of the small size of the Java mouse-deer, dogs are also a common predator for them, as well as crocodiles, big cats, birds of prey, and snakes.[15]

Diseases

Although research into the diseases and parasites which affect the Java mouse-deer are still nascent, bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV 1), a pestivirus of the family flaviviridae has been detected in Java mouse-deer. Mouse-deer acquire this virus through fetal infection during early pregnancy. Once acquired, individuals with BVDV can gain lifelong immune tolerance.[18]

Conservation status

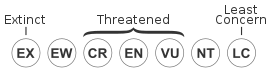

Java mouse-deer is currently categorized as “Data Deficient” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List.[1] This data deficiency is due to the inconclusiveness regarding the distinct separation of Tragulus species, in addition to the lack of information on Tragulus javanicus. Even comparison of past observed numbers of Java mouse-deer with those presently observed does not greatly aid researchers because of the high likelihood of inaccuracy in past observations. Although listed as “Data Deficient,” it is highly probable that a decline in the numbers of Java mouse-deer is occurring, and upon further investigation of this issue, the Red List status of Tragulus javanicus could easily change to “Vulnerable”.[1] Some conservation actions which have been implemented include legally protecting the species, which, although it has been in effect since 1931, makes no significant difference since hunting of Java mouse-deer still occurs. Additionally, some areas of Java which the Java mouse-deer frequents have been protected, yet enforcement of these regulations is still needed. One of the greatest conservation efforts needed is simply more information about the species: a more complete definition of its taxonomy, as well as more information on its habitat and behavior.

Indonesian folklore

Historically, the mouse-deer has featured prominently in Malay and Indonesian folklore, where it is considered a wise creature. This character, Sang Kancil (pronounced “Kahn-cheel”), is a diminutive but wise mouse-deer. Sang Kancil is a tiny and cunning hero who, through his intelligence, is able to prevail over his larger tyrants and foes.[19][20]

References

- Duckworth, J. W.; Hedges, S.; Timmins, R. J.; Semiadi, G. (2008). "Tragulus javanicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 2014-04-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 649–650. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Meijaard, I.; Groves, C. P. (2004). "A taxonomic revision of the Tragulus mouse-deer". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140: 63–102. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00091.x.

- Javan mouse-deer (Tragulus javanicus). (2013). ARKive - Discover the world's most endangered species. Retrieved from http://www.arkive.org/javan-mouse-deer/tragulus-javanicus Archived 2013-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Facts about Lesser Mouse Deer (Tragulus javanicus) - Encyclopedia of Life. (n.d.). Encyclopedia of Life - Animals - Plants - Pictures & Information. Retrieved from http://eol.org/pages/328339/names/synonyms

- Facts about Lesser Mouse Deer (Tragulus javanicus) - Encyclopedia of Life. (n.d.). Encyclopedia of Life - Animals - Plants - Pictures & Information. Retrieved from http://eol.org/pages/328339/

- Meijaard, E.; Groves, C. P. (2004). "A Taxonomic Revision Of The Tragulus Mouse-deer (Artiodactyla)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (1): 63–102. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00091.x.

- Java Mouse Deer, Tragulus javanicus - Mammals Reference Library - redOrbit. (n.d.). redOrbit - Science, Space, Technology, Health News and Information. Retrieved from http://www.redorbit.com/education/reference_library/science_1/mammalia/1112721404/java-mouse-deer-tragulus-javanicus/

- Nowak, R., J. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Chicago: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Fukuta, K.; Kudo, H; Jalaludin, S. (1996). "Unique pits on the erythrocytes of the lesser mouse-deer, Tragulus javanicus". Journal of Anatomy. 189 (1): 211–213. PMC 1167845. PMID 8771414.

- Matsubayashi, Hisashi; Bosi, Edwin; Kohshima, Shiro (28 February 2003). <0234:AAHUOL>2.0.CO;2 "Activity and Habitat Use of Lesser Mouse-Deer (Tragalus javanicus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 84 (1): 234–242. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0234:AAHUOL>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-2372.

- Carwardine, M., & London, E. (2007). Animal records. New York: Sterling

- Strawder, N. (2000). ADW: Tragulus javanicus. ADW: Home. Retrieved from http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Tragulus_javanicus/

- Matsubayashi, H.; Bosi, E.; Kohshima, S. (2003). "Activity And Habitat Use Of Lesser Mouse-Deer (Tragulus Javanicus)" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 84 (1): 234–242. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0234:aahuol>2.0.co;2.

- Prothero, D. R., & Foss, S. E. (2007). The evolution of artiodactyls. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Hayssen, V., & Tienhoven, A. v. (1993). Asdell's patterns of mammalian reproduction: a compendium of species-specific data. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

- Kingdon, J. (1989). East African mammals : an atlas of evolution in Africa. London: Academic Press

- Uttenthal, A.; Hoyer, M. J.; Grøndahl, C.; Houe, H.; van Maanen, C; Rasmussen, T. B.; et al. (2006). "Vertical Transmission Of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus (BVDV) In Mousedeer (Tragulus Javanicus) And Spread To Domestic Cattle". Archives of Virology. 151 (12): 2377–2387. doi:10.1007/s00705-006-0818-8. PMID 16835699.

- The Lesser Mouse Deer - A Tiny Superhero - pictures and facts. (n.d.). Animal pictures | Facts about mammals. Retrieved from http://thewebsiteofeverything.com/animals/mammals/Artiodactyla/Tragulidae/Tragulus/Tragulus-javanicus.html

- Shepard, A. (2005) The Adventures of Mouse Deer: Tales of Indonesia and Malaysia. Aaron Shepard's Home Page. Retrieved from http://www.aaronshep.com/rt/RTE35.html

External links

![]()