Mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue, sometimes accompanied by a thin mucousal muscle layer, which separates the mucosa from the submucosa. It is mostly of endodermal origin and is continuous with the skin at various body openings such as the eyes, ears, inside the nose, inside the mouth, lip, vagina, glans penis, the urethral opening and the anus. Some mucous membranes secrete mucus, a thick protective fluid. The function of the membrane is to stop pathogens and dirt from entering the body and to prevent bodily tissues from becoming dehydrated.

| Mucous membrane | |

|---|---|

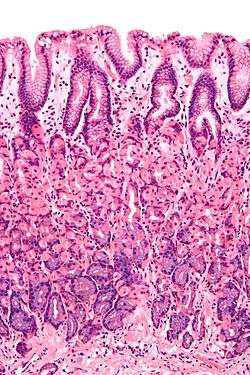

Histological section taken from the gastric antrum, showing the mucosa of the stomach | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | endoderm |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica mucosa |

| MeSH | D009092 |

| TA | A05.4.01.015 A05.3.01.029 A05.5.01.029 A05.6.01.009 A05.6.01.010 A05.7.01.006 A05.7.01.007 A05.8.02.009 A06.1.02.017 A06.2.09.019 A06.3.01.010 A06.4.02.029 A08.1.05.011 A08.2.01.007 A08.3.01.023 A09.1.02.013 A09.1.04.011 A09.2.03.012 A09.3.05.010 A09.3.06.004 A09.4.02.015 A09.4.02.020 A09.4.02.029 A15.3.02.083 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

|

| This article is one of a series on the |

| Gastrointestinal wall |

|---|

|

General structure |

|

Specific

|

|

Organs |

Structure

The mucosa of organs are composed of one or more layers of epithelial cells that secrete mucus, and an underlying lamina propria of loose connective tissue.[1] The type of cells and type of mucus secreted vary from organ to organ and each can differ along a given tract.[2] The muscularis mucosae is a thin layer of smooth muscle that builds the outermost layer of mucosa in some parts of the gastrointestinal and urinary tract. It supports the mucous membrane and allows it the ability to move and fold.[3]

Mucous membranes line the digestive, respiratory, and reproductive tracts and are the primary barrier between the external world and the interior of the body; in an adult human the total surface area of the mucosa is about 400 square meters while the surface area of the skin is about 2 square meters.[4]:1 They are at several places contiguous with skin: at the nostrils, the lips of the mouth, the eyelids, the ears, the genital area, and the anus.[1] Along with providing a physical barrier, they also contain key parts of the immune system and serve as the interface between the body proper and the microbiome.[2]:437

Mucus lake

In the mucosa, there are mucus-filled colloid areas and a few basophilic glandular elements. The cells are in spaces filled with mucus appearing as "lakes".[5]

Examples

Some examples include:

- Bronchial mucosa and the lining of vocal folds

- Endometrium: the mucosa of the uterus

- Esophageal mucosa

- Gastric mucosa

- Intestinal mucosa

- Nasal mucosa

- Olfactory mucosa

- Oral mucosa

- Penile mucosa

- Vaginal mucosa

- Frenulum of tongue

- Tongue

- Anal canal

- Palpebral conjunctiva

Development

Developmentally, the majority of mucous membranes are of endodermal origin.[6] Exceptions include the palate, cheeks, floor of the mouth, gums, lips and the portion of the anal canal below the pectinate line, which are all ectodermal in origin.[7][8]

Function

Two of its functions is to keep the tissue moist (for example in the respiratory tract, including the mouth and nose).[2]:480 It also plays a role in absorbing and transforming nutrients.[2]:5,813 Mucous membranes also protect the body from itself; for instance mucosa in the stomach protects it from stomach acid,[2]:384,797 and mucosa lining the bladder protects the underlying tissue from urine.[9] In the uterus, the mucous membrane is called the endometrium, and it swells each month and is then eliminated during menstruation.[2]:1019

Nutrition

Niacin[2]:876 and vitamin A are essential nutrients that help maintain mucous membranes.[10]

See also

- Alkaline mucus

- Mucin

- Mucociliary clearance

- Mucocutaneous boundary

- Mucosal immunology

- Rete pegs

References

- "Mucous membrane". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Guyton, Arthur C.; Hall, John E. (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- "GI Tract Lab". medcell.med.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- Sompayrac, Lauren (2012). How the Immune System Works (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118290446.

- Sherman F. Stinson, Hildegard M. Schuller, Gerd Reznik (1990). Atlas of Tumor Pathology of the Fischer Rat. p. 176.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Chapter 25. Germ Layers and Their Derivatives - Review of Medical Embryology Book - LifeMap Discovery". discovery.lifemapsc.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

- Squier, Christopher; Brogden, Kim (2010-12-29). "Chapter 7, Development and aging of the oral mucosa". Human Oral Mucosa: Development, Structure and Function. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470959732.

- Schoenwolf, Gary C.; Bleyl, Steven B.; Brauer, Philip R.; Francis-West, Philippa H. (2014-12-01). Larsen's Human Embryology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 372. ISBN 9781455727919.

- Fry, CH; Vahabi, B (October 2016). "The Role of the Mucosa in Normal and Abnormal Bladder Function". Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 119 Suppl 3: 57–62. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12626. PMC 5555362. PMID 27228303.

- "Vitamin A". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. February 2, 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2017.