Collared peccary

The collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) is a species of mammal in the family Tayassuidae found in North, Central, and South America. They are commonly referred to as javelina, saíno, or báquiro, although these terms are also used to describe other species in the family. The species is also known as the musk hog. In Trinidad, it is colloquially known as quenk.

| Collared peccary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Tayassuidae |

| Genus: | Pecari |

| Species: | P. tajacu |

| Binomial name | |

| Pecari tajacu | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Sus tajacu Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Although somewhat related to the pigs and frequently referred to as one, this species and the other peccaries are no longer classified in the pig family, Suidae.

Description

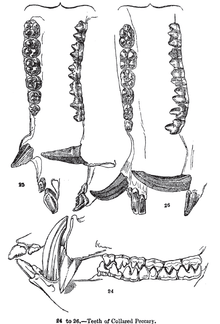

The collared peccary stands around 510–610 mm (20–24 in) tall at the shoulder and is about 1.0–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in–4 ft 11 in) long. It weighs between 16 and 27 kg (35 and 60 lb).[2] The dental formula is as followed: 2/3,1/1,3/3,3/3.[3] The collared peccary has small tusks that point toward the ground when the animal is upright. It also has slender legs with a robust or stocky body. The tail is often hidden in the coarse fur of the peccary.[4]

Range and habitat

The collared peccary is a widespread creature found throughout much of the tropical and subtropical Americas, ranging from the Southwestern United States to northern Argentina in South America. They have been reintroduced to Uruguay in 2017, after 100 years of extinction.[5] The only Caribbean island where it is native, however, is Trinidad. It was once and until fairly recently also extant on the nearby island of Tobago, but is now exceedingly rare (if not locally extirpated) due to overhunting by humans. It inhabits deserts and xeric shrublands, tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands, flooded grasslands and savannas, tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, and several other habitats, as well. In addition, it is well adapted to habitats shared by humans, merely requiring sufficient cover; they can be found in cities and agricultural land throughout their range, where they consume garden plants. Notable populations are known to exist in the suburbs of Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona.[6][7]

Diet

Collared peccaries are omnivorous. They normally feed on cactus, mesquite beans, fruits, roots, tubers, palm nuts, grasses, invertebrates, and small vertebrates. In areas inhabited by humans, they also consume cultivated crops and ornamental plants, such as tulip bulbs.[6][7]

Behaviour

Collared peccaries are diurnal creatures that live in groups of up to 50 individuals, averaging between six and 9 members. They sleep in burrows, often under the roots of trees, but sometimes can be found in caves or under logs.[4] However, collared peccaries are not completely diurnal. In central Arizona, they are often active at night, but less so in daytime.

Although they usually ignore humans, they will react if they feel threatened. They defend themselves with their tusks. A collared peccary can release a strong musk or give a sharp bark if it is alarmed.[4]

Gallery

Running collared peccary

Running collared peccary Mother and juvenile

Mother and juvenile- A Pueblo drinking vessel

References

- Gongora, J.; Reyna-Hurtado, R.; Beck, H.; Taber, A.; Altrichter, M. & Keuroghlian, A. (2011). "Pecari tajacu". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T41777A10562361. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T41777A10562361.en. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- "Collared Peccary: Javelina ~ Tayaussa ~ Musk Hog". Digital West Media Inc. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Reid, Fiona (2006). Peterson Field Guide: Mammals of North America (4th ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-395-93596-5.

- Reid, Fiona (2006). Peterson Field Guide: Mammals of North America (4th ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-395-93596-5.

- "A un año de su liberación, los pecaríes ya se adaptaron y tienen cría". ecos.la (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Friederici, Peter (August–September 1998). "Winners and Losers". National Wildlife Magazine. National Wildlife Federation. 36 (5).

- Sowls, Lyle K. (1997). Javelinas and Other Peccaries: Their Biology, Management, and Use (2nd ed.). Texas A&M University Press. pp. 61–68. ISBN 978-0-89096-717-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pecari tajacu. |