Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial

The Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial is a memorial site in France dedicated to the commemoration of Dominion of Newfoundland forces members who were killed during World War I. The 74-acre (300,000 m2) preserved battlefield park encompasses the grounds over which the Newfoundland Regiment made their unsuccessful attack on 1 July 1916 during the first day of the Battle of the Somme.[1]

| Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial | |

|---|---|

| Veterans Affairs Canada Commonwealth War Graves Commission | |

Caribou statue, Newfoundland Regiment Memorial, Beaumont-Hamel | |

| For the Newfoundland Regiment on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme and World War I Newfoundland forces members whose graves are unknown. | |

| Unveiled | 7 June 1925 |

| Location | 50°04′25″N 02°38′53″E near |

| Designed by | Rudolph Cochius (landscape) Basil Gotto (memorial) |

| Commemorated | 814 |

To the Glory of God and in perpetual remembrance of those officers and men of the Newfoundland Forces who gave their lives by Land and Sea in the Great War and who have no known graves. | |

| Statistics source: Cemetery details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. | |

| Official name | Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1996 |

The Battle of the Somme was the regiment's first major engagement, and during an assault that lasted approximately 30 minutes the regiment was all but wiped out. Purchased in 1921 by the people of Newfoundland, the memorial site is the largest battalion memorial on the Western Front, and the largest area of the Somme battlefield that has been preserved. Along with preserved trench lines, there are a number of memorials and cemeteries contained within the site.

Officially opened by British Field Marshal Earl Haig in 1925, the memorial site is one of only two National Historic Sites of Canada located outside of Canada. (The other is the Canadian National Vimy Memorial). The memorial site and experience of the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont-Hamel has come to represent the Newfoundland First World War experience. As a result, it has become a Newfoundland symbol of sacrifice and a source of identity.

Background

During the First World War, Newfoundland was a largely rural Dominion of the British Empire with a population of 240,000, and not yet part of Canada.[2] The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 led the Government of Newfoundland to recruit a force for service with the British Army.[3] Even though the island had not possessed any formal military organization since 1870, enough men soon volunteered that an entire battalion was formed, and later maintained throughout the war.[4] The regiment trained at various locations in the United Kingdom and increased from an initial contingent of 500 men to full battalion strength of 1,000 men, before being deployed.[5] After a period of acclimatization in Egypt, the regiment was deployed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula with the 29th British Division in support of the Gallipoli Campaign.[6] With the close of the Gallipoli Campaign the regiment spent a short period recuperating before being transferred to the Western Front in March 1916.[7]

Battle of the Somme

_1.jpg)

In France, the regiment regained battalion strength in preparation for the Battle of the Somme. The regiment, still with the 29th British Division, went into the line in April 1916 at Beaumont-Hamel.[8] Beaumont-Hamel was situated near the northern end of the 45-kilometre front being assaulted by the joint French and British force. The attack, originally scheduled for 29 June 1916 was postponed by two days to July 1, 1916, partly on account of inclement weather, partly to allow more time for the artillery preparation.[9] The 29th British Division, with its three infantry brigades faced defences manned by experienced troops of the 119th (Reserve) Infantry Regiment of the 26th (Wurttemberg) Reserve Division.[10] The 119th (Reserve) Infantry Regiment had been involved in the invasion of France in August 1914 and had been manning the Beaumont-Hamel section of the line for nearly 20 months prior to the battle.[10] The German troops were spending a great deal of their time not only training but fortifying their position, including the construction of numerous deep dugouts and at least two tunnels.[10][11]

The infantry assault by the 29th British Division on 1 July 1916 was to be preceded ten minutes earlier by a mine explosion under the heavily fortified Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt.[12] The explosion of the 18,000 kilogram (40,000 lb) Hawthorn Mine underneath the German lines successfully destroyed a major enemy strong point but also served to alert the German forces to the imminent attack.[13] Following the explosion, troops of the 119th (Reserve) Infantry Regiment immediately deployed from their dugouts into the firing line, even preventing the British from taking control of the resulting crater as they had planned.[Note 1] When the assault finally began, the troops from the 86th and 87th Brigade of the 29th British Division were quickly stopped. With the exception of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers on the right flank, the initial assault foundered in No Man's Land at, or short of, the German barbed wire.[15] At divisional headquarters, Major-General Beauvoir De Lisle and his staff were trying to unravel the numerous and confusing messages coming back from observation posts, contact aircraft and the two leading brigades. There were indications that some troops had broken into and gone beyond the German first line.[Note 2] In an effort to exploit the perceived break in the German line he ordered the 88th Brigade, which was in reserve, to send forward two battalions to support attack.[16]

At 8:45 a.m. the Newfoundland Regiment and 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment received orders to move forward.[16] The Newfoundland Regiment was situated at St. John's Road, a support trench 250 yards (230 m) behind the British forward line and out of sight of the enemy.[17] Movement forward through the communication trenches was not possible because they were congested with dead and wounded men and under shell fire.[18] Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Lovell Hadow, the battalion commander, decided to move immediately into attack formation and advance across the surface, which involved first navigating through the British barbed wire defences.[17] As they breasted the skyline behind the British first line, they were effectively the only troops moving on the battlefield and clearly visible to the German defenders.[18] Subjected to the full force of the 119th (Reserve) Infantry Regiment, most of the Newfoundland Regiment who had started forward were dead, dying or wounded within 15 to 20 minutes of leaving St. John's Road trench.[19] Most reached no further than the Danger Tree, a skeleton of a tree that lay in No Man's Land that was being utilized as a landmark.[20] So far as can be ascertained, 22 officers and 758 other ranks were directly involved in the advance.[20] Of these, all the officers and slightly under 658 other ranks became casualties.[20] Of the 780 men who went forward only about 110 survived unscathed, of whom only 68 were available for roll call the following day.[20] For all intents and purposes the Newfoundland Regiment had been wiped out, the unit as a whole having suffered a casualty rate of approximately 80%. The only unit to suffer greater casualties during the attack was the 10th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment, attacking west of Fricourt village.[21]

The rest of the war

Major-General Sir Beauvoir De Lisle referring to the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont-Hamel

After July 1916, the Beaumont-Hamel front remained relatively quiet while the Battle of the Somme continued to the south. In the final act in the Somme Offensive, Beaumont-Hamel was assaulted by the 51st (Highland) Division on 13 November 1916 on the opening of the Battle of the Ancre.[23] Within two days, all the 29th Division objectives of 1 July had been taken along with a great many German prisoners.[24] The area of the memorial site then became a rear area with troops lodged in the former German dugouts and a camp was established in the vicinity of the present Y Ravine Cemetery.[25] With the German withdrawal in March 1917 to the Hindenburg Line, about 30 kilometres from Beaumont-Hamel, the battlefield salvage parties moved in, many dugouts were closed off and initial efforts were probably made to restore some of the land to agriculture.[25] However, in March 1918, the German Spring Offensive was here checked on exactly the same battle lines as before.[26] Until the Battle of Amiens and the German withdrawal in late August 1918, the protagonists confronted each other over the same ground, although the only actions were those of routine front line trench raids, patrols and artillery harassment.[27]

History

In 1921, Newfoundland purchased the ground over which the Newfoundland Regiment made its unsuccessful attack during the first day of the Battle of the Somme.[28] Much of the credit for the establishment of the 74-acre (300,000 m2) memorial site is given to Lieutenant Colonel Tom Nangle, the former Roman Catholic Priest of the regiment.[25][29] As Director of Graves Registration and Enquiry and Newfoundland's representative on the Imperial War Graves Commission he negotiated with some 250 French landowners for the purchase of the site.[29] He also played a leading role in selecting and developing the sites where the Newfoundland memorials currently stand, as well as supervising the construction of each memorial.[29] The memorials, including that at the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site, were constructed for the Government of Newfoundland between 1924 and 1925.[30]

The Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site was officially opened, and the memorial unveiled, by Field Marshal Earl Haig on 7 June 1925.[29] Since Newfoundland's confederation with Canada in 1949, the Canadian Government, through the Department of Veterans Affairs, has been responsible for the site's maintenance and care.[31] The site had fallen into some disrepair during the German occupation of France in the Second World War and following confederation the replacement of the original site cabin with a modern building as well as some trench restoration work was undertaken in time for the 45th anniversary of the battle.[31] The memorial site was established as one of only two National Historic Sites of Canada located outside of Canada by the then Minister of Canadian Heritage Sheila Copps on 10 April 1997.[32]

The site

The Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site is situated 9 kilometres (6 mi) north of Albert, France near the village of Beaumont-Hamel in an area containing numerous cemeteries and memorials related to the Battle of the Somme.[33] The site is one of the few places on the former Western Front where a visitor can see the trench lines of the First World War and the related terrain in a preserved natural state.[34][35] It is the largest site dedicated to the memory of the Newfoundland Regiment, the largest battalion memorial on the Western Front, and the largest area of the Somme battlefield that has been preserved.[36]

Although the site was founded to honour the memory of the Newfoundland Regiment, it also contains a number of memorials as well as four cemeteries maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission; that of Y Ravine Cemetery, Hawthorn Ridge Cemeteries No. 1 and No. 2 and the unusual mass burial site of Hunter's Cemetery.[33] Beyond being a popular location for battlefield tours the site is also an important location in the burgeoning field of First World War battlefield archaeology, because of its preserved and largely undisturbed state.[37][38] The ever-increasing number of visitors to the Memorial has resulted in the authorities taking measures to control access by fencing off certain areas of the former battlefield.[39]

29th Division Memorial

Near the entrance to site is situated a memorial to the 29th British Division, the division of which the Newfoundland Regiment was a part. Lieutenant-General Beauvoir De Lisle, wartime commander of the 29th British Division, unveiled the monument the morning of the official opening of the site on 7 June 1925.[29] Each wartime unit of the 29th British Division sent a representative to form a guard of honour for the occasion.[29] Afterwards, this detachment, joined by French infantry from Arras formed the honour guard for the unveiling of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial.[29]

Newfoundland Regiment Memorial

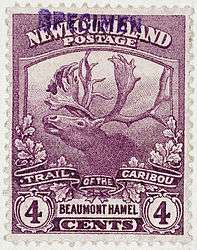

The memorial is one of six identical memorials erected following the First World War. Five were erected in France and Belgium by the Government of Newfoundland and the sixth at Bowring Park in St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada.[40][Note 3] The sixth memorial was not a national war memorial but rather a gift of Major William Howe Greene who donated it to Bowring Park. The memorial is a bronze caribou, the emblem of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, standing atop a cairn of Newfoundland granite facing the former foe with head thrown high in defiance. At the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site the mound rises approximately 50 feet (15 m) from ground level.[41] The mounds are also surrounded by native Newfoundland plants. At the base of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial mound, three bronze tablets carry the names of 820 members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve, and the Mercantile Marines who gave their lives in the First World War and have no known grave.[41] The memorial is situated close to the headquarters dugout of the 88th Brigade, the brigade of which the Newfoundland Regiment was a part. Sixteen memorial designs were submitted to Nangle for review. He recommended that the government accept British sculptor Basil Gotto’s plan to erect five identical caribou statues in memory of the regiment.[42][30] Gotto was already well known in Newfoundland as he had been previously commissioned to execute the statue of the Fighting Newfoundlander located in Bowring Park.[29] The landscape architect who designed the sites and supervised their construction, was Rudolph Cochius, a native of the Netherlands living in St. John's.[29] It was decided to plant many of Newfoundland’s native tree species, such as spruce, dogberry and juniper, along the boundaries of the site.[30] In total, over 5,000 trees were transplanted before the project was completed in 1925.[30] The memorial was unveiled at the official opening of the site by Field Marshal Earl Haig on 7 June 1925.[29] Those that participated or were present included Chief of the French General Staff, Marshal of France Marie Émile Fayolle, Newfoundland Colonial Secretary John Bennett, Lieutenant Generals Aylmer Hunter-Weston and Beauvoir De Lisle, Major-General D. E. Cayley and former regimental commanding officers Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Lovell and Adolph Ernest Bernard.[29]

51st Division Monument

Overlooking Y Ravine is the memorial to 51st (Highland) Division. The ground originally donated by the commune of Beaumont-Hamel to the Veterans of the 51st Division was found to be unstable because of the many dugouts beneath it.[25] Lieutenant Colonel Nangle offered a location overlooking Y Ravine within the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site.[25] The Y ravine had been the scene of fierce fighting for the division on 13 November 1916.[23] The selected sculptor for the 51st Division Monument was George Henry Paulin.[43] The base of the monument consists of rough blocks of Rubislaw granite which were produced by Garden & Co. in Aberdeen, Scotland, and are assembled in a pyramid form.[25] Company Sergeant Major Bob Rowan of the Glasgow Highlanders was used as the model for the kilted figure atop the memorial.[25] The figure faces east towards the village of Beaumont-Hamel. On the front is a plaque inscribed in Gaelic: La a'Blair s'math n Cairdean which in English translates as "Friends are good on the day of battle".[44] The 51st Division Monument was unveiled on 28 September 1924 by Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch, the former Allied Supreme Commander.[45] The memorial was rededicated on 13 July 1958, the front panel now referring to not only those who died during the First World War but the Second as well. A wooden Celtic cross directly across the track from the memorial was originally sited at High Wood and subsequently moved to the Newfoundland site.[25] The cross commemorates the men of the 51st Highland Division who fell at High Wood in July 1916.[25]

The Danger Tree

The Danger Tree had been part of a clump of trees located about halfway into No Man's Land and had originally been used as a landmark by a Newfoundland Regiment trench raiding party in the days before the Battle of the Somme.[18] British and German artillery bombardments eventually stripped the tree of leaves and left nothing more than a shattered tree trunk.[18] During the Newfoundland Regiment's infantry assault, the tree was once again used as a landmark, where the troops were ordered to gather. The tree was however a highly visible landmark for the German artillery and the site proved to be a location where the German shrapnel was particularly deadly. As a result, the regiment suffered a large concentration of casualties around the tree.[18] A replica representation of the twisted tree now stands at the spot.[25]

Visitors Centre

There is a Visitors' Centre which exhibits the historical and social circumstances of Newfoundland at the beginning of the 20th century and traces the history of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and some of its personalities.[25] A Memorial room within the Centre houses a copy of the Newfoundland Book of Remembrance, along with a bronze plaque listing the Battle Honours won by the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.[25] The centre also incorporates the administrative offices and site archive. Canadian student guides based at the site are available to provide guided tours or explain particular facets of the battlefield and the Newfoundland involvement.[25]

Influence on Newfoundland

The significance of the events at Beaumont-Hamel on the first day of the Battle of the Somme was perhaps most strongly felt by the Dominion of Newfoundland, as it was the first great conflict experienced by that dominion. Newfoundland was left with a sense of loss that marked an entire generation.[46][47] The effects on the post-war generation were compounded by chronic financial problems caused both by Newfoundland's large debt from the war, and a prolonged post-war economic recession due to a decline in the fisheries.[48][49]

Lasting impressions of the war experience are ever-prevalent on the island. In Canada, 1 July is celebrated as Canada Day, in recognition of Canadian confederation. In the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador the date is Memorial Day, in remembrance of the Newfoundland Regiment's losses at Beaumont-Hamel.[Note 4] Memorial University College, now Memorial University of Newfoundland, was originally established as a memorial to Newfoundlanders who had lost their lives in active service during the First World War.[51] Lastly, the six caribou memorials and the National War Memorial erected following the First World War, and the establishment of the preserved battlefield park at Beaumont-Hamel which is visited by thousands of tourists a year. The Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial site also serves an informal ambassadorial function, educating visitors not only about the experience of the Newfoundland Regiment but also regarding the history of the island.[25]

Notes

- Quoting the diaries of the German 119th (Reserve) Infantry Regiment.[14]

- A German flare to indicate shells were falling short of target was mistakenly identified as a British flare used to indicate the first objective had been taken.[16]

- Of these five, four were erected in France, and one in Belgium. The French caribou memorials are: this one at Beaumont-Hamel; the Gueudecourt (Newfoundland) Memorial, the Monchy-le-Preux (Newfoundland) Memorial; and the memorial at Masnières. The Belgian caribou memorial is at Courtrai.

- Memorial Day has been recognized since 1917, during Newfoundland's Dominion period.[50]

Footnotes

- Jacqueline Hucker (2012). "Monuments of the First and Second World Wars". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Foundation. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Hopkins pp. 153–156

- Nicholson p. 98

- Nicholson p. 88

- Nicholson pp. 121–154

- Nicholson pp. 155–192

- Nicholson p. 480

- Nicholson pp. 239–242

- Nicholson pp. 253, 261

- Nicholson p. 243

- Sheldon p. 66

- Rose & Nathanail p. 404

- Rose & Nathanail pp. 404–405

- Nicholson p. 264–265

- Nicholson p. 266

- Nicholson p. 268

- Nicholson p. 270

- Nicholson p. 271

- Nicholson pp. 270, 273

- Nicholson p. 274

- Farr p. 88

- Gilbert p. 64

- Gilbert p. 235

- Gilbert p. 235–238

- "Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial". Veterans Affairs Canada. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Gilbert p. 252–253

- Gilbert p. 254

- Nicholson p. 282

- Nicholson p. 518

- "Commemorations: Overseas". Newfoundland and the Great War. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. n.d. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- Nicholson p. 533

- "Beaumont-Hamel National Historic Site of Canada". Historic Places. Parks Canada. 2 April 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "CWGC :: Cemetery Details – Beaumont-Hamel (Newfoundland) Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. n.d. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Rose & Nathanail p. 216

- Lloyd p. 120

- "Somme > The Somme Revisited > The Battlefield Today > Battlefield Tour 1 > Newfoundland Memorial Park Beaumont-Hamel". Imperial War Museum. n.d. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Saunders pp. 101–108

- Dolamore pp. 12–17

- Gough p. 699

- Busch p. 151

- Nicholson p. 517

- Nicholson p. 516

- Dolman p. 532

- Salmond p. 271

- Salmond p. 270

- Steele p. 200–201

- Busch pp. 150, 157

- Steele p. 14

- Busch p. 157

- Nicholson p. 283

- "Welcome to Memorial | History". Memorial University of Newfoundland. 30 March 2006. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

References

- Boyer, Robert (Summer 2006). "The Battle of the Somme – 90th Anniversary: The 1st Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont Hamel, 1st July 1916" (PDF). Canadian Army Journal. Department of National Defence. 9 (2): 4–8. ISSN 1712-9745. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012.

- Busch, Briton Cooper (2003). Canada and the Great War: Western Front Association Papers. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2570-X.

- Dolamore, Mike (2001). "Seeing beneath the battlefield – geophysical prospection at the Vimy and Newfoundland Memorial Parks (News from the Durand Group)". Battlefields Review. Wharncliffe Publishing Ltd (15): 12–17.

- Gilbert, Martin (2006). The Somme: Heroism and Horror in the First World War. New York: Henry Hold & Co. ISBN 0-8050-8127-5.

- Gough, Paul (2007). "'Contested memories: Contested site': Newfoundland and its unique heritage on the Western Front". The Round Table. 96 (393): 693–705.

- Hopkins, John Castell (1916). The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs – 1915. Toronto: Annual Review Publishing Company Limited.

- Dolman, Bernard (1954). Who's who in Art. London: Art Trade Press, Ltd.

- Farr, Don (2007). The Silent General: A Biography of Haig's Trusted Great War Comrade-in-Arms. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-874622-99-4.

- Lloyd, David (1998). Battlefield tourism: pilgrimage and the commemoration of the Great War in Britain, Australia and Canada, 1919–1939. Oxford: Berg Publishing. ISBN 1-85973-174-0.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L. (1962). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L. (2006) [1964]. The Fighting Newfoundlander: A History of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. Carleton Library; 209 (2nd ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-3133-5.

- Rose, Edward (2000). Geology and Warfare: Examples of the Influence of Terrain and Geologists on Military Operations. London: Geological Society. ISBN 0-85052-463-6.

- Salmond, James Bell (1953). The history of the 51st Highland Division, 1939–1945. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons.

- Saunders, Nicholas (2002). "Excavating memories: archaeology and the Great War, 1914–2001". Antiquity. Portland Press. 76 (291): 101–108.

- Sheldon, Jack (2006). The Germans at Beaumont Hamel. London: Pen and Swords Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-443-2.

- Steele, Owen William (2003). David Richard Facey-Crowther (ed.). Lieutenant Owen William Steele of the Newfoundland Regiment: diary and letters. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2428-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial. |

- Newfoundland and the Great War by Heritage Newfoundland

- Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial

- Beaumont-Hamel Memorial Park at Find a Grave

- Newfoundland Memorial at Find a Grave