People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the armed forces of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and its founding and ruling political party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[6] The PLA consists of five professional service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, Rocket Force, and the Strategic Support Force. Units around the country are assigned to one of five theater commands by geographical location. The PLA is the world's largest military force and constitutes the second largest defence budget in the world. The PLA is one of the fastest modernising militaries in the world and has been termed as a potential military superpower, with significant regional power and rising global power projection capabilities.[7][8][1][9][10][11][12] As per Credit Suisse in 2015, the PLA is the world's third-most powerful military.[13]

| Chinese People's Liberation Army | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民解放军 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民解放軍 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "China People Liberation Army" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The PLA is under the command of the Central Military Commission (CMC) of the CCP. It is legally obliged to follow the principle of civilian control of the military, although in practical terms this principle has been implemented in such a way as to ensure the PLA is under the absolute control of the Communist Party. Its commander in chief is the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (usually the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China).[14] Since 1949, China has used nine different military strategies, which the PLA calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[15] In times of national emergency, the People's Armed Police and the China Militia act as a reserve and support element for the PLAGF.

Mission statement

Former paramount leader Hu Jintao had defined the missions of the PLA as:[16]

- To consolidate the ruling status of the Communist Party

- To ensure China's sovereignty, territorial integrity, and domestic security to continue national development

- To safeguard China's national interests

- To help maintain world peace

History

Second Sino-Japanese War

The People's Liberation Army was founded on 1 August 1927 during the Nanchang uprising when troops of the Kuomintang (KMT) rebelled under the leadership of Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying and Zhou Enlai after the Shanghai massacre of 1927 by Chiang Kai-shek. They were then known as the Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, or simply the Red Army. Between 1934 and 1935, the Red Army survived several campaigns led against it by Chiang Kai-Shek and engaged in the Long March.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945, the Communist military forces were nominally integrated into the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China forming two main units known as the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army. During this time, these two military groups primarily employed guerrilla tactics, generally avoiding large-scale battles with the Japanese with some exceptions while at the same time consolidating their ground by absorbing nationalist troops and paramilitary forces behind Japanese lines into their forces. After the Japanese surrendered in 1945, the Communist Party merged the Eighth Route Army and New Fourth Army, renaming the new million-strong force the "People's Liberation Army". They eventually won the Chinese Civil War, establishing the People's Republic of China in 1949. The PLA then saw a huge reorganisation with the establishment of the Air Force leadership structure in November 1949 followed by the Navy leadership the following April. In 1950, the leadership structures of the artillery, armoured troops, air defence troops, public security forces, and worker–soldier militias were also established. The chemical warfare defence forces, the railroad forces, the communications forces, and the strategic forces, as well as other separate forces (like engineering and construction, logistics and medical services), were established later on, all these depended on the leadership of the Communist Party and the National People's Congress via the Central Military Commission (and until 1975 the National Defense Council).

1950s, 1960s and 1970s

During the 1950s, the PLA with Soviet assistance began to transform itself from a peasant army into a modern one.[17] Since 1949, China has used nine different military strategies, which the PLA calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[15] Part of this process was the reorganisation that created thirteen military regions in 1955. The PLA also contained many former National Revolutionary Army units and generals who had defected to the PLA. Ma Hongbin and his son Ma Dunjing were the only two Muslim generals who led a Muslim unit, the 81st corps, to ever serve in the PLA. Han Youwen, a Salar Muslim general, also defected to the PLA. In November 1950, some units of the PLA under the name of the People's Volunteer Army intervened in the Korean War as United Nations forces under General Douglas MacArthur approached the Yalu River. Under the weight of this offensive, Chinese forces drove MacArthur's forces out of North Korea and captured Seoul, but were subsequently pushed back south of Pyongyang north of the 38th Parallel. The war also served as a catalyst for the rapid modernization of the PLAAF. In 1962, the PLA ground force also fought India in the Sino-Indian War, achieving all objectives.

Prior to the Cultural Revolution, military region commanders tended to remain in their posts for long periods of time. As the PLA took a stronger role in politics, this began to be seen as somewhat of a threat to the party's (or, at least, civilian) control of the military. The longest-serving military region commanders were Xu Shiyou in the Nanjing Military Region (1954–74), Yang Dezhi in the Jinan Military Region (1958–74), Chen Xilian in the Shenyang Military Region (1959–73), and Han Xianchu in the Fuzhou Military Region (1960–74). The establishment of a professional military force equipped with modern weapons and doctrine was the last of the Four Modernizations announced by Zhou Enlai and supported by Deng Xiaoping. In keeping with Deng's mandate to reform, the PLA has demobilized millions of men and women since 1978 and has introduced modern methods in such areas as recruitment and manpower, strategy, and education and training. In 1979, the PLA fought Vietnam over a border skirmish in the Sino-Vietnamese War where both sides claimed victory.

During the Sino-Soviet split, strained relations between China and the Soviet Union resulted in bloody border clashes and mutual backing of each other's adversaries. China and Afghanistan had neutral relations with each other during the King's rule. When the pro-Soviet Afghan Communists seized power in Afghanistan in 1978, relations between China and the Afghan communists quickly turned hostile. The Afghan pro-Soviet communists supported China's enemies in Vietnam and blamed China for supporting Afghan anti-communist militants. China responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by supporting the Afghan mujahideen and ramping up their military presence near Afghanistan in Xinjiang. China acquired military equipment from the United States to defend itself from Soviet attack.[18]

The People's Liberation Army Ground Force trained and supported the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War, moving its training camps for the mujahideen from Pakistan into China itself. Hundreds of millions of dollars worth of anti-aircraft missiles, rocket launchers, and machine guns were given to the Mujahidin by the Chinese. Chinese military advisors and army troops were also present with the Mujahidin during training.[19]

Since 1980

In 1981, the PLA conducted its largest military exercise in North China since the founding of the People's Republic. In the 1980s, China shrunk its military considerably to free up resources for economic development, resulting in the relative decline in resources devoted to the PLA. Following the PLA's suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, ideological correctness was temporarily revived as the dominant theme in Chinese military affairs. Reform and modernisation have today resumed their position as the PLA's primary objectives, although the armed forces' political loyalty to the CPC has remained a leading concern. Another area of concern to the political leadership was the PLA's involvement in civilian economic activities. These activities were thought to have impacted PLA readiness and has led the political leadership to attempt to divest the PLA from its non-military business interests.

Beginning in the 1980s, the PLA tried to transform itself from a land-based power centred on a vast ground force to a smaller, more mobile, high-tech one capable of mounting operations beyond its borders. The motivation for this was that a massive land invasion by Russia was no longer seen as a major threat, and the new threats to China are seen to be a declaration of independence by Taiwan, possibly with assistance from the United States, or a confrontation over the Spratly Islands. In 1985, under the leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the CMC, the PLA changed from being constantly prepared to "hit early, strike hard and to fight a nuclear war" to developing the military in an era of peace. The PLA reoriented itself to modernization, improving its fighting ability, and to become a world-class force. Deng Xiaoping stressed that the PLA needed to focus more on quality rather than on quantity. The decision of the Chinese government in 1985 to reduce the size of the military by one million was completed by 1987. Staffing in military leadership was cut by about 50 percent. During the Ninth Five Year Plan (1996–2000) the PLA was reduced by a further 500,000. The PLA had also been expected to be reduced by another 200,000 by 2005. The PLA has focused on increasing mechanisation and informatization so as to be able to fight a high-intensity war.[20]

Former CMC chairman Jiang Zemin in 1990 called on the military to "meet political standards, be militarily competent, have a good working style, adhere strictly to discipline, and provide vigorous logistic support" (Chinese: 政治合格、军事过硬、作风优良、纪律严明、保障有力; pinyin: zhèngzhì hégé, jūnshì guòyìng, zuòfēng yōuliáng, jìlǜ yánmíng, bǎozhàng yǒulì).[21] The 1991 Gulf War provided the Chinese leadership with a stark realisation that the PLA was an oversized, almost-obsolete force. The possibility of a militarised Japan has also been a continuous concern to the Chinese leadership since the late 1990s. In addition, China's military leadership has been reacting to and learning from the successes and failures of the American military during the Kosovo War, the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the Iraqi insurgency. All these lessons inspired China to transform the PLA from a military based on quantity to one based on quality. Chairman Jiang Zemin officially made a "Revolution in Military Affairs" (RMA) part of the official national military strategy in 1993 to modernise the Chinese armed forces. A goal of the RMA is to transform the PLA into a force capable of winning what it calls "local wars under high-tech conditions" rather than a massive, numbers-dominated ground-type war. Chinese military planners call for short decisive campaigns, limited in both their geographic scope and their political goals. In contrast to the past, more attention is given to reconnaissance, mobility, and deep reach. This new vision has shifted resources towards the navy and air force. The PLA is also actively preparing for space warfare and cyber-warfare.

For the past 10 to 20 years, the PLA has acquired some advanced weapons systems from Russia, including Sovremenny class destroyers, Sukhoi Su-27 and Sukhoi Su-30 aircraft, and Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines. It has also started to produce several new classes of destroyers and frigates including the Type 052D class guided missile destroyer. In addition, the PLAAF has designed its very own Chengdu J-10 fighter aircraft and a new stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20. The PLA launched the new Jin class nuclear submarines on 3 December 2004 capable of launching nuclear warheads that could strike targets across the Pacific Ocean and have two aircraft carriers, one commissioned in 2012 and a second launched in 2017.

In 2015, the PLA formed new units including the PLA Ground Force, the PLA Rocket Force and the PLA Strategic Support Force.[22]

The PLA on 1 August 2017 marked the 90th anniversary since its establishment, before the big anniversary it mounted its biggest parade yet and the first outside of Beijing, held in the Zhurihe Training Base in the Northern Theater Command (within the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region), the first time it had ever been done to mark PLA Day as past parades had already been on 1 October, National Day of the PRC.

Peacekeeping operations

The People's Republic of China has sent the PLA to various hotspots as part of China's role as a prominent member of the United Nations. Such units usually include engineers and logistical units and members of the paramilitary People's Armed Police and have been deployed as part of peacekeeping operations in Lebanon,[23] the Republic of the Congo,[24] Sudan,[25] Ivory Coast,[26] Haiti,[27] and more recently, Mali and South Sudan.

Notable events

- 1927–1950: Chinese Civil War

- 1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War

- 1949: Yangtze incident against British warships on the Yangtze river.

- 1949: Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China

- 1950: Incorporation of Tibet into the People's Republic of China

- 1950–1953: Korean War under the banner of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army.

- 1954–1955: First Taiwan Strait Crisis.

- 1955–1970: Vietnam War.

- 1958: Second Taiwan Strait Crisis at Quemoy and Matsu.

- 1962: Sino-Indian War.

- 1967: Border skirmishes with India.

- 1969: Sino-Soviet border conflict.

- 1974: Battle of the Paracel Islands with South Vietnam.

- 1979: Sino-Vietnamese War.

- 1979–1990: Sino-Vietnamese conflicts 1979–1990.

- 1988: Johnson South Reef Skirmish with Vietnam.

- 1989: Enforcement of martial law in Beijing during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

- 1990: Baren Township riot.

- 1995–1996: Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.

- 1997: PLA Control of Hong Kong's Military Defense

- 1999: PLA Control of Macau's Military Defense

- 2007–present: UNIFIL peacekeeping operations in Lebanon

- 2009–present: Anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden

- 2014: Search and rescue efforts for Flight MH370

- 2014: UN Peacekeeping operations in Mali

- 2014–present: Conflict against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

- 2015: UNMISS peacekeeping operations in South Sudan

Organization

National military command

The state military system upholds the principle of the CPC's absolute leadership over the armed forces. The party and the State jointly established the CMC that carries out the task of supreme military leadership over the armed forces. The 1954 Constitution stated that the State President directs the armed forces and made the State President the chairman of the Defense Commission. The Defense Commission is an advisory body and does not hold any actual power over the armed forces. On 28 September 1954, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party re-established the CMC as the commanding organ of the PLA. From that time onward, the current system of a joint system of party and state leadership of the military was established. The Central Committee of the Communist Party leads in all military affairs. The State President directs the state military forces and the development of the military forces which is managed by the State Council.

To ensure the absolute leadership of the Communist Party over the armed forces, every level of party committee in the military forces implements the principles of democratic centralism. In addition, division-level and higher units establish political commissars and political organisations, ensuring that the branch organisations are in line. These systems combined the party organisation with the military organisation to achieve the party's leadership and administrative leadership. This is seen as the key guarantee to the absolute leadership of the party over the military.

In October 2014 the PLA Daily reminded readers of the Gutian Congress, which stipulated the basic principle of the Party controlling the military, and called for vigilance as "[f]oreign hostile forces preach the nationalization and de-politicization of the military, attempting to muddle our minds and drag our military out from under the Party's flag."[28]

Military leadership

The leadership by the CPC is a fundamental principle of the Chinese military command system. The PLA reports not to the State Council but rather to two Central Military Commissions, one belonging to the state and one belonging to the party.

In practice, the two central military commissions usually do not contradict each other because their membership is usually identical. Often, the only difference in membership between the two occurs for a few months every five years, during the period between a party congress, when Party CMC membership changes, and the next ensuing National People's Congress, when the state CMC changes. The CMC carries out its responsibilities as authorised by the Constitution and National Defense Law.[29]

The leadership of each type of military force is under the leadership and management of the corresponding part of the Central Military Commission of the CPC Central Committee. Forces under each military branch or force such as the subordinate forces, academies and schools, scientific research and engineering institutions and logistical support organisations are also under the leadership of the CMC. This arrangement has been especially useful as China over the past several decades has moved increasingly towards military organisations composed of forces from more than one military branch. In September 1982, to meet the needs of modernisation and to improve co-ordination in the command of forces including multiple service branches and to strengthen unified command of the military, the CMC ordered the abolition of the leadership organisation of the various military branches. Today, the PLA has air force, navy and second artillery leadership organs.

In 1986, the People's Armed Forces Department, except in some border regions, was placed under the joint leadership of the PLA and the local authorities. Although the local party organisations paid close attention to the People's Armed Forces Department, as a result of some practical problems, the CMC decided that from 1 April 1996, the People's Armed Forces Department would once again fall under the jurisdiction of the PLA.

According to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China, the CMC is composed of the following: the Chairman, Vice-Chairmen and Members. The Chairman of the Central Military Commission has overall responsibility for the commission.

- Chairman

- Xi Jinping (also General Secretary, President and Commander-in-chief of Joint Battle Command)

- Vice Chairmen

- Air Force General Xu Qiliang

- General Zhang Youxia

- Members

- Minister of National Defense – General Wei Fenghe

- Chief of the Joint staff – General Li Zuocheng

- Director of the Political Work Department – Admiral Miao Hua

- Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection – General Zhang Shengmin

Central Military Commission

In December 1982, the fifth National People's Congress revised the state constitution to state that the State Central Military Commission leads all the armed forces of the state. The chairman of the State CMC is chosen and removed by the full NPC while the other members are chosen by the NPC standing committee. However, the CMC of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party remained the party organisation that directly commands the military and all the other armed forces.

In actual practice, the party CMC, after consultation with the democratic parties, proposes the names of the State CMC members of the NPC so that these people after going through the legal processes can be elected by the NPC to the State Central Military Commission. That is to say, that the CMC of the Central Committee and the CMC of the State are one group and one organisation. However, looking at it organizationally, these two CMCs are subordinate to two different systems – the party system and the state system. Therefore, the armed forces are under the absolute leadership of the Communist Party and are also the armed forces of the state. This is a unique joint leadership system that reflects the origin of the PLA as the military branch of the Communist Party. It only became the national military when the People's Republic of China was established in 1949.

By convention, the chairman and vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission are civilian members of the Communist Party of China, but they are not necessarily the heads of the civilian government. Both Jiang Zemin and Deng Xiaoping retained the office of chairman even after relinquishing their other positions. All of the other members of the CMC are uniformed active military officials. Unlike other nations, the Minister of National Defense is not the head of the military, but is usually a vice-chairman of the CMC.

In 2012, to attempt to reduce corruption at the highest rungs of the leadership of the Chinese military, the commission banned the service of alcohol at military receptions.[30]

2016 military reforms

On 1 January 2016, The Central Military Commission (CMC) released a guideline[31] on deepening national defense and military reform, about a month after CMC Chairman Xi Jinping called for an overhaul of the military administration and command system at a key meeting.

On 11 January 2016, the PLA created a joint staff directly attached to the Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest leadership organization in the military. The previous four general headquarters of the PLA were disbanded and completely reformed. They were divided into 15 functional departments instead — a significant expansion from the domain of the General Office, which is now a single department within the Central Military Commission .

- General Office (办公厅)

- Joint Staff Department (联合参谋部)

- Political Work Department (政治工作部)

- Logistic Support Department (后勤保障部)

- Equipment Development Department (装备发展部)

- Training and Administration Department (训练管理部)

- National Defense Mobilization Department (国防动员部)

- Discipline Inspection Commission (纪律检查委员会)

- Politics and Legal Affairs Commission (政法委员会)

- Science and Technology Commission (科学技术委员会)

- Office for Strategic Planning (战略规划办公室)

- Office for Reform and Organizational Structure (改革和编制办公室)

- Office for International Military Cooperation (国际军事合作办公室)

- Audit Office (审计署)

- Agency for Offices Administration (机关事务管理总局)

Included among the 15 departments are three commissions. The CMC Discipline Inspection Commission is charged with rooting out corruption.

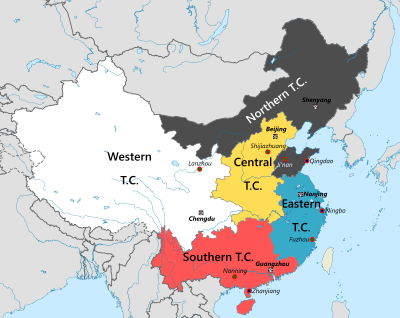

Theater commands

Until 2016, China's territory was divided into seven military regions, but they were reorganized into five theater commands in early 2016. This reflects a change in their concept of operations from primarily ground-oriented to mobile and coordinated movement of all services.[33] The five new theatre commands are:

- Eastern Theater Command

- Western Theater Command

- Northern Theater Command

- Southern Theater Command

- Central Theater Command

The PLA garrisons in Hong Kong and Macau both come under the Southern Theater Command.

The military reforms have also introduced a major change in the areas of responsibilities. Rather than separately commanding their own troops, service branches are now primarily responsible for administrative tasks (like equipping and maintaining the troops). It is the theater commands now that have the command authority. This should, in theory, facilitate the implementation of joint operations across all service branches.[34]

Coordination with civilian national security groups such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is achieved primarily by the leading groups of the Communist Party of China. Particularly important are the leading groups on foreign affairs, which include those dealing with Taiwan.

Service branches

The PLA encompasses five main service branches: the Ground Force, the Navy, the Air Force, the Rocket Force, and the Strategic Support Force. Following the 200,000 troop reduction announced in 2003, the total strength of the PLA has been reduced from 2.5 million to just under 2.3 million. Further reforms will see an additional 300,000 personnel reduction from its current strength of 2.28 million personnel. The reductions will come mainly from non-combat ground forces, which will allow more funds to be diverted to naval, air, and strategic missile forces. This shows China's shift from ground force prioritisation to emphasising air and naval power with high-tech equipment for offensive roles over disputed coastal territories.[35]

In recent years, the PLA has paid close attention to the performance of US forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. As well as learning from the success of the US military in network-centric warfare, joint operations, C4ISR, and hi-tech weaponry, the PLA is also studying unconventional tactics that could be used to exploit the vulnerabilities of a more technologically advanced enemy. This has been reflected in the two parallel guidelines for the PLA ground forces development. While speeding up the process of introducing new technology into the force and retiring the older equipment, the PLA has also placed an emphasis on asymmetric warfare, including exploring new methods of using existing equipment to defeat a technologically superior enemy.

In addition to the four main service branches, the PLA is supported by two paramilitary organisations: the People's Armed Police (including the China Coast Guard) and the Militia (including the maritime militia).

Ground Force

The PLA has a ground force with 975,000 personnel, about half of the PLA's total manpower of around 2 million.[36] The ground forces are divided among the five theatre commands as named above. In times of crisis, the PLA Ground Force will be reinforced by numerous reserve and paramilitary units. The PLAGF reserve component has about 510,000 personnel divided into 30 infantry and 12 anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) divisions. In recent years two amphibious mechanised divisions were also established in Nanjing and Guangzhou MR. At least 40 percent of PLA divisions and brigades are now mechanised or armoured, almost double the percentage before 2015.

While much of the PLA Ground Force was being reduced over the past few years, technology-intensive elements such as special operations forces (SOF), army aviation, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and electronic warfare units have all been rapidly expanded. The latest operational doctrine of the PLA ground forces highlights the importance of information technology, electronic and information warfare, and long-range precision strikes in future warfare. The older generation telephone/radio-based command, control, and communications (C3) systems are being replaced by an integrated battlefield information networks featuring local/wide-area networks (LAN/WAN), satellite communications, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based surveillance and reconnaissance systems, and mobile command and control centres.[37]

On 1 January 2016, as part of military reforms, China created for the first time a separate headquarters for the ground forces.[38] China's ground forces have never had their own headquarters until now. Previously, the People's Liberation Army's Four General Departments served as the de facto army headquarters, functioning together as the equivalent of a joint staff, to which the navy, air force and the newly renamed Rocket Force would report. The Commander of the PLA Ground Force is Han Weiguo. The Political Commissar is Liu Lei.

Navy

Until the early 1990s, the navy performed a subordinate role to the PLA Land Forces. Since then it has undergone rapid modernisation. The 240,000 strong People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is organised into three major fleets: the North Sea Fleet headquartered at Qingdao, the East Sea Fleet headquartered at Ningbo, and the South Sea Fleet headquartered in Zhanjiang. Each fleet consists of a number of surface ship, submarine, naval air force, coastal defence, and marine units.[39]

The navy includes a 15,000 strong Marine Corps (organised into two brigades), a 26,000 strong Naval Aviation Force operating several hundred attack helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.[40] As part of its overall programme of naval modernisation, the PLAN is in the stage of developing a blue water navy. In November 2012, then Party General Secretary Hu Jintao reported to the Chinese Communist Party 18th National Congress his desire to "enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resource and build China into a strong maritime power".[41]

Air Force

The 395,000 strong People's Liberation Army Air Force is organised into five Theater Command Air Forces (TCAF) and 24 air divisions.[42] The largest operational units within the Aviation Corps is the air division, which has 2 to 3 aviation regiments, each with 20 to 36 aircraft. The surface-to-air missile (SAM) Corps is organised into SAM divisions and brigades. There are also three airborne divisions manned by the PLAAF. J-XX and XXJ are names applied by Western intelligence agencies to describe programs by the People's Republic of China to develop one or more fifth-generation fighter aircraft.[43][44]

Rocket Force

The 100,000 strong People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) is the main strategic missile force of the PLA.[45] It controls China's nuclear and conventional strategic missiles. China's total nuclear arsenal size is estimated to be between 100 and 400 (thermo)nuclear weapons. The PLARF has approximately 100,000 personnel and six ballistic missile divisions (missile corps bases). The six divisions are independently deployed in different theater commands and have a total of 15 to 20 missile brigades.

Strategic Support Force

Founded on 31 December 2015 as part of the first wave of reforms of the PLA, the People's Liberation Army Strategic Support Force is the newest branch of the PLA. It as strength of 175,000.[46] Initial announcements regarding the Strategic Support Force did not provide much detail, but Yang Yujun of the Chinese Ministry of Defense described it as a combination of all support forces. Additionally, commentators speculate that it will include high-tech operations forces such as space, cyberspace and electronic warfare operations units, independent of other branches of the military.[47] Another expert, Yin Zhuo, said that "the major mission of the PLA Strategic Support Force is to give support to the combat operations so that the PLA can gain regional advantages in the astronautic war, space war, network war and electromagnetic space war and ensure smooth operations."[48]

Conscription and terms of service

Technically, military service with the PLA is obligatory for all Chinese citizens. In practice, mandatory military service has not been implemented since 1949 as the People's Liberation Army has been able to recruit sufficient numbers voluntarily.[49] All 18-year-old males have to register themselves with the government authorities, in a way similar to the Selective Service System of the United States. In practice, registering does not mean that the person doing so must join the People's Liberation Army.[50]

Article 55 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China prescribes conscription by stating: "It is a sacred duty of every citizen of the People's Republic of China to defend his or her motherland and resist invasion. It is an honoured obligation of the citizens of the People's Republic of China to perform military service and to join the militia forces."[51] The 1984 Military Service Law spells out the legal basis of conscription, describing military service as a duty for "all citizens without distinction of race... and religious creed". This law has not been amended since it came into effect. Technically, those 18–22 years of age enter selective compulsory military service, with a 24-month service obligation. In reality, numbers of registering personals are enough to support all military posts in China, creating so-called "volunteer conscription".[52]

Residents of the Special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, are exempted from joining the military.

Military intelligence

Joint Staff Department

The Joint Staff Department carries out staff and operational functions for the PLA and had major responsibility for implementing military modernisation plans. Headed by chief of general staff, the department serves as the headquarters for the entire PLA and contained directorates for the five armed services: Ground Forces, Air Force, Navy, Rocket Forces and Support Forces. The Joint Staff Department included functionally organised subdepartments for operations, training, intelligence, mobilisation, surveying, communications and politics, the departments for artillery, armoured units, quartermaster units and joint forces engineering units were later dissolved, with the former two forming now part of the Ground Forces, the engineering formations now split amongst the service branches and the quartermaster formations today form part of the Joint Logistics Forces.

Navy Headquarters controls the North Sea Fleet, East Sea Fleet, and South Sea Fleet. Air Force Headquarters generally exercised control through the commanders of the five theater commands. Nuclear forces were directly subordinate to the Joint Staff Department through the Rocket Forces commander and political commissar. Conventional main, regional, and militia units were controlled administratively by the theater commanders, but the Joint Staff Department in Beijing could assume direct operational control of any main-force unit at will. Thus, broadly speaking, the Joint Staff Department exercises operational control of the main forces, and the theater commanders controlled as always the regional forces and, indirectly, the militia. The post of principal intelligence official in the top leadership of the Chinese military has been taken up by a number of people of several generations, from Li Kenong in the 1950s to Xiong Guangkai in the late 1990s; and their public capacity has always been assistant to the deputy chief of staff or assistant to the chief of staff.

Ever since the CPC officially established the system of "theater commands" for its army in the 2010s as a successor to the "major military regions" policy of the 1950s, the intelligence agencies inside the Army have, after going through several major evolutions, developed into the present three major military intelligence setups:

- The central level is composed of the Second and Third Departments under the Joint Staff Headquarters and the Liaison Department under the Political Work Department.

- At the Theater Command level intelligence activities consist of the Second Bureau established at the same level as the Operation Department under the headquarters, and the Liaison Department established under the Political Work Department.

- The third system includes a number of communications stations directly established in the garrison areas of all the theater commands by the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters.

The Second Bureau under the headquarters and the Liaison Department under the Political Work Departments of the theater commands are only subjected to the "professional leadership" of their "counterpart" units under the Central Military Commission and are still considered the direct subordinate units of the major military region organizationally. Those entities whose names include the word "institute", all research institutes under the charge of the Second and the Third Departments of the Joint Staff Headquarters, including other research organs inside the Army, are at least of the establishment size of the full regimental level. Among the deputy commanders of a major Theater command in China, there is always one who is assigned to take charge of intelligence work, and the intelligence agencies under his charge are directly affiliated to the headquarters and the political department of the corresponding theater command.

The Conference on Strengthening Intelligence Work held from 3 September 1996 – 18 September 1996 at the Xishan Command Center of the Ministry of State Security and the General Staff Department. Chi Haotian delivered a report entitled "Strengthen Intelligence Work in a New International Environment To Serve the Cause of Socialist Construction." The report emphasised the need to strengthen the following four aspects of intelligence work:

- Efforts must be made to strengthen understanding of the special nature and role of intelligence work, as well as understanding of the close relationship between strengthening intelligence work on the one hand, and of the Four Modernizations of the motherland, the reunification of the motherland, and opposition to hegemony and power politics on the other.

- The United States and the West have all along been engaged in infiltration, intervention, sabotage, and intelligence gathering against China on the political, economic, military, and ideological fronts. The response must strengthen the struggle against their infiltration, intervention, sabotage, and intelligence gathering.

- Consolidating intelligence departments and training a new generation of intelligence personnel who are politically reliable, honest and upright in their ways, and capable of mastering professional skills, the art of struggle, and advanced technologies.

- Strengthening the work of organising intelligence in two international industrial, commercial, and financial ports—Hong Kong and Macau.

Although the four aspects emphasised by Chi Haotian appeared to be defensive measures, they were in fact both defensive and offensive in nature.

Second Department

The Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters is responsible for collecting military intelligence. Activities include military attachés at Chinese embassies abroad, clandestine special agents sent to foreign countries to collect military information, and the analysis of information publicly published in foreign countries. This section of the PLA Joint Staff Headquarters act in similar capacity to its civilian counterpart the Ministry of State Security.

The Second Department oversees military human intelligence (HUMINT) collection, widely exploits open source (OSINT) materials, fuses HUMINT, signals intelligence (SIGINT), and imagery intelligence data, and disseminates finished intelligence products to the CMC and other consumers. Preliminary fusion is carried out by the Second Department's Analysis Bureau which mans the National Watch Center, the focal point for national-level indications and warning. In-depth analysis is carried out by regional bureaus. Although traditionally the Second Department of the Joint Staff Department was responsible for military intelligence, it is beginning to increasingly focus on scientific and technological intelligence in the military field, following the example of Russian agencies in stepping up the work of collecting scientific and technological information.

The research institute under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters is publicly known as the Institute for International Strategic Studies; its internal classified publication "Foreign Military Trends" ("外军动态", Wai Jun Dongtai) is published every 10 days and transmitted to units at the division level.

The PLA Institute of International Relations at Nanjing comes under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Department and is responsible for training military attachés, assistant military attachés and associate military attachés as well as secret agents to be posted abroad. It also supplies officers to the military intelligence sections of various military regions and group armies. The institute was formed from the PLA "793" Foreign Language Institute, which moved from Zhangjiakou after the Cultural Revolution and split into two institutions at Luoyang and Nanjing.

The Institute of International Relations was known in the 1950s as the School for Foreign Language Cadres of the Central Military Commission, with the current name being used since 1964. The training of intelligence personnel is one of several activities at the institute. While all graduates of the Moscow Institute of International Relations were employed by the KGB, only some graduates of the Beijing Institute of International Relations are employed by the Ministry of State Security. The former Institute of International Relations, since been renamed the Foreign Affairs College, is under the administration of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is not involved in secret intelligence work. The former Central Military Commission foreign language school had foreign faculty members who were either Communist Party sympathizers or were members of foreign communist parties. But the present Institute of International Relations does not hire foreign teachers, to avoid the danger that its students might be recognised when sent abroad as clandestine agents.

Those engaged in professional work in military academies under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters usually have a chance to go abroad, either for advanced studies or as military officers working in the military attaché's office of Chinese embassies in foreign countries. People working in the military attaché's office of embassies are usually engaged in collecting military information under the cover of "military diplomacy". As long as they refrain from directly subversive activities, they are considered as well-behaved "military diplomats".

Some bureaus under the Second Department which are responsible for espionage in different regions, of which the First Bureau is responsible for collecting information in the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, and also in Taiwan. Agents are dispatched by the Second Department to companies and other local corporations to gain cover.

The "Autumn Orchid" intelligence group assigned to Hong Kong and Macau in the mid-1980s mostly operated in the mass media, political, industrial, commercial, and religious circles, as well as in universities and colleges. The "Autumn Orchid" intelligence group was mainly responsible for the following three tasks:

- Finding out and keeping abreast of the political leanings of officials of the Hong Kong and Macau governments, as well as their views on major issues, through social contact with them and through information provided by them.

- Keeping abreast of the developments of foreign governments' political organs in Hong Kong, as well as of foreign financial, industrial, and commercial organisations.

- Finding out and having a good grasp of the local media's sources of information on political, military, economic, and other developments on the mainland, and deliberately releasing false political or military information to the media to test the outside response.

The "Autumn Orchid" intelligence group was awarded a Citation for Merit, Second Class, in December 1994. It was further awarded another Citation for Merit, Second Class, in 1997. Its current status is not publicly known. During the 2008 Chinese New Year celebration CCTV held for Chinese diplomatic establishments, the head of the Second Department of the Joint Headquarters was revealed for the first time to the public: the current head was Major General Yang Hui (杨晖).

Third Department

The Third Department of the Joint Staff Department is responsible for monitoring the telecommunications of foreign armies and producing finished intelligence based on the military information collected.

The communications stations established by the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters are not subject to the jurisdiction of the provincial military district and the major theater command of where they are based. The communications stations are entirely the agencies of the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters which have no affiliations to the provincial military district and the military region of where they are based. The personnel composition, budgets, and establishment of these communications stations are entirely under the jurisdiction of the Third Department of the General PLA General Staff Headquarters, and are not related at all with local troops.

China maintains the most extensive SIGINT network of all the countries in the Asia-Pacific region. As of the late 1990s, SIGINT systems included several dozen ground stations, half a dozen ships, truck-mounted systems, and airborne systems. Third Department headquarters is in the vicinity of the GSD First Department (Operations Department), AMS, and NDU complex in the hills northwest of the Summer Palace. As of the late 1990s, the Third Department was allegedly manned by approximately 20,000 personnel, with most of their linguists trained at the Luoyang Institute of Foreign Languages.

Ever since the 1950s, the Second and Third Departments of the Joint Staff Headquarters have established a number of institutions of secondary and higher learning for bringing up "special talents." The PLA Foreign Language Institute at Luoyang comes under the Third Department of the Joint Staff Department and is responsible for training foreign language officers for the monitoring of foreign military intelligence. The institute was formed from the PLA "793" Foreign Language Institute, which moved from Zhangjiakou after the Cultural Revolution and split into two institutions at Luoyang and Nanjing.

Though the distribution order they received upon graduation indicated the "Joint Staff Headquarters", many of the graduates of these schools found themselves being sent to all parts of the country, including remote and uninhabited backward mountain areas. The reason is that the monitoring and control stations under the Third Department of the PLA General Staff Headquarters are scattered in every corner of the country.

The communications stations located in the Shenzhen base of the PLA Hong Kong Garrison started their work long ago. In normal times, these two communications stations report directly to the Central Military Commission and the Joint Staff Headquarters. Units responsible for co-ordination are the communications stations established in the garrison provinces of the military regions by the Third Department of the PLA General Staff Headquarters.

By taking direct command of military communications stations based in all parts of the country, the CPC Central Military Commission and the Joint Staff Headquarters can not only ensure a successful interception of enemy radio communications, but can also make sure that none of the wire or wireless communications and contacts among major military regions can escape the detection of these communications stations, thus effectively attaining the goal of imposing a direct supervision and control over all major military regions, all provincial military districts, and all group armies.

Monitoring stations

China's main SIGINT effort is in the Third Department of the Joint Staff Department of the Central Military Commission, with additional capabilities, primarily domestic, in the Ministry of State Security (MSS). SIGINT stations, therefore, are scattered through the country, for domestic as well as international interception. Prof. Desmond Ball, of the Australian National University, described the largest stations as the main Technical Department SIGINT net control station on the northwest outskirts of Beijing, and the large complex near Lake Kinghathu in the extreme northeast corner of China.

As opposed to other major powers, China focuses its SIGINT activities on its region rather than the world. Ball wrote, in the eighties, that China had several dozen SIGINT stations aimed at the Soviet Union, Japan, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and India, as well as internally. Of the stations apparently targeting Russia, there are sites at Jilemutu and Jixi in the northeast, and at Erlian and Hami near the Mongolian border. Two Russian-facing sites in Xinjiang, at Qitai and Korla may be operated jointly with resources from the US CIA's Office of SIGINT Operations, probably focused on missile and space activity. Other stations aimed at South and Southeast Asia are on a net controlled by Chengdu, Sichuan. There is a large facility at Dayi, and, according to Ball, "numerous" small posts along the Indian border. Other significant facilities are located near Shenyang, near Jinan and in Nanjing and Shanghai. Additional stations are in the Fujian and Guangdong military districts opposite Taiwan.

On Hainan Island, near Vietnam, there is a naval SIGINT facility that monitors the South China sea, and a ground station targeting US and Russian satellites. China also has ship and aircraft platforms in this area, under the South Sea Fleet headquarters at Zhanjiang immediately north of the island. Targeting here seems to have an ELINT as well as COMINT flavor. There are also truck-mounted mobile ground systems, as well as ship, aircraft, and limited satellite capability. There are at least 10 intelligence-gathering auxiliary vessels.

As of the late nineties, the Chinese did not appear to be trying to monitor the United States Pacific Command to the same extent as does Russia. In future, this had depended, in part, on the status of Taiwan.

Fourth Department

The Fourth Department (ECM and Radar) of the Joint Staff Headquarters Department has the electronic intelligence (ELINT) portfolio within the PLA's SIGINT apparatus. This department is responsible for electronic countermeasures, requiring them to collect and maintain data bases on electronic signals. 25 ELINT receivers are the responsibility of the Southwest Institute of Electronic Equipment (SWIEE). Among the wide range of SWIEE ELINT products is a new KZ900 airborne ELINT pod. The GSD 54th Research Institute supports the ECM Department in development of digital ELINT signal processors to analyse parameters of radar pulses.

Liaison Department

The Political Work Department maintains the CPC structure that exists at every level of the PLA. It is responsible for overseeing the political education, indoctrination and discipline that is a prerequisite for advancement within the PLA. The PWD controls the internal prison system of the PLA. The International Liaison Department of the Political Work Department is publicly known as the China Association for International Friendly Contact.[53][54] The department prepares political and economic information for the reference of the Political Bureau. The department conducts ideological and political work on foreign armies, explaining China's policies, and disintegrate enemy armies by dampening their morale. It is also tasked with instigating rebellions and disloyalty within the Taiwan military and other foreign militaries.

The Liaison Office has dispatched agents to infiltrate Chinese-funded companies and private institutions in Hong Kong. Their mission is counter-espionage, monitoring their own agents, and preventing and detecting foreign intelligence services buying off Chinese personnel.

Special forces

.jpg)

China's special ground force is called PLASF (People's Liberation Army Special Operations Forces). It includes highly trained soldiers, a team of commander, assistant commander, sniper, spotter, machine-gun supporter, bomber, and a pair of assault groups.[55] China's counter terrorist unit is drawn from the police force rather than the military. The name changes frequently. As of 2020, it is known as the Immediate Action Unit (IAU).[56]

China has reportedly developed a force capable of carrying out long-range airborne operations, long-range reconnaissance, and amphibious operations. Formed in China's Guangzhou military region and known by the nickname "Sword of Southern China", the force supposedly receives army, air force, and naval training, including flight training, and is equipped with "hundreds of high-tech devices", including global-positioning satellite systems. All of the force's officers have completed military staff colleges, and 60 percent are said to have university degrees. Soldiers are reported to be cross-trained in various specialties, and training is supposed to encompass a range of operational environments. It is far from clear whether this unit is considered operational by the Chinese. It is also not clear how such a force would be employed. Among the missions mentioned were "responding to contingencies in various regions" and "cooperating with other services in attacks on islands". According to the limited reporting, the organisation appears to be in a phase of testing and development and may constitute an experimental unit. While no size for the force has been revealed, there have been Chinese media claims that "over 4,000 soldiers of the force are all-weather and versatile fighters and parachutists who can fly airplanes and drive auto vehicles and motor boats".

Other branches

- The Third Department and the Navy co-operate on shipborne intelligence collection platforms.

- PLAAF Sixth Research Institute: Air Force SIGINT collection is managed by the PLAAF Sixth Research Institute in Beijing.

Weapons and equipment

According to the United States Defense Department, China is developing kinetic-energy weapons, high-powered lasers, high-powered microwave weapons, particle-beam weapons, and electromagnetic pulse weapons with its increase of military fundings.[57]

The PLA has said of reports that its modernisation is dependent on sales of advanced technology from American allies "Some people have politicized China's normal commercial cooperation with foreign countries, smearing our reputation." These contributions include advanced European diesel engines for Chinese warships, military helicopter designs from Eurocopter, French anti-submarine sonars and helicopters,[58] Australian technology for the Houbei class missile boat,[59] and Israeli supplied American missile, laser and aircraft technology.[60]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's data, China became the world's third largest exporter of major arms in 2010–14, an increase of 143 percent from the period 2005–2009.[61] SIPRI also calculated that China surpassed Russia to become the world's second largest arms exporter by 2020.[62] China's share of global arms exports hence increased from 3 to 5 percent. China supplied major arms to 35 states in 2010–14. A significant percentage (just over 68 percent) of Chinese exports went to three countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. China also exported major arms to 18 African states. Examples of China's increasing global presence as an arms supplier in 2010–14 included deals with Venezuela for armoured vehicles and transport and trainer aircraft, with Algeria for three frigates, with Indonesia for the supply of hundreds of anti-ship missiles and with Nigeria for the supply of a number of unmanned combat aerial vehicles. Following rapid advances in its arms industry, China has become less dependent on arms imports, which decreased by 42 percent between 2005–2009 and 2010–14. Russia accounted for 61 percent of Chinese arms imports, followed by France with 16 percent and Ukraine with 13 per cent. Helicopters formed a major part of Russian and French deliveries, with the French designs produced under licence in China. Over the years, China has struggled to design and produce effective engines for combat and transport vehicles. It continued to import large numbers of engines from Russia and Ukraine in 2010–14 for indigenously designed combat, advanced trainer and transport aircraft, and for naval ships. It also produced British-, French- and German-designed engines for combat aircraft, naval ships and armoured vehicles, mostly as part of agreements that have been in place for decades.[63]

Cyberwarfare

There is a belief in the western military doctrines that the PLA have already begun engaging countries using cyber-warfare.[64][65] There has been a significant increase in the number of presumed Chinese military initiated cyber events from 1999 to the present day.[66]

Cyberwarfare has gained recognition as a valuable technique because it is an asymmetric technique that is a part of Chinese Information Operations. As is written by two PLAGF Colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, "Methods that are not characterised by the use of the force of arms, nor by the use of military power, nor even by the presence of casualties and bloodshed, are just as likely to facilitate the successful realisation of the war's goals, if not more so.[67]

While China has long been suspected of cyber spying, on 24 May 2011 the PLA announced the existence of their cyber security squad.[68]

In February 2013, the media named "Comment Crew" as a hacker military faction for China's People's Liberation Army.[69] In May 2014, a Federal Grand Jury in the United States indicted five Unit 61398 officers on criminal charges related to cyber attacks on private companies.[70][71]

In February 2020, the United States government indicted members of China's People's Liberation Army for the 2017 Equifax data breach, which involved hacking into Equifax and plundering sensitive data as part of a massive heist that also included stealing trade secrets, though the Chinese Communist Party denied these claims.[72][73]

Nuclear weapons

In 1955, China decided to proceed with a nuclear weapons program. The decision was made after the United States threatened the use of nuclear weapons against China should it take action against Quemoy and Matsu, coupled with the lack of interest of the Soviet Union for using its nuclear weapons in defence of China.

After their first nuclear test (China claims minimal Soviet assistance before 1960) on 16 October 1964, China was the first state to pledge no-first-use of nuclear weapons. On 1 July 1966, the Second Artillery Corps, as named by Premier Zhou Enlai, was formed. In 1967, China tested a fully functional hydrogen bomb, only 32 months after China had made its first fission device. China thus produced the shortest fission-to-fusion development known in history.

China became a major international arms exporter during the 1980s. Beijing joined the Middle East arms control talks, which began in July 1991 to establish global guidelines for conventional arms transfers, and later announced that it would no longer participate because of the US decision to sell 150 F-16A/B aircraft to Taiwan on 2 September 1992.

It joined the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1984 and pledged to abstain from further atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in 1986. China acceded to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1992 and supported its indefinite and unconditional extension in 1995. Nuclear weapons tests by China ceased in 1996, when it signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and agreed to seek an international ban on the production of fissile nuclear weapons material.

In 1996, China committed to provide assistance to unsafeguarded nuclear facilities. China attended the May 1997 meeting of the NPT Exporters (Zangger) Committee as an observer and became a full member in October 1997. The Zangger Committee is a group which meets to list items that should be subject to IAEA inspections if exported by countries, which have, as China has, signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty. In September 1997, China issued detailed nuclear export control regulations. China began implementing regulations establishing controls over nuclear-related dual-use items in 1998. China also has decided not to engage in new nuclear co-operation with Iran (even under safeguards), and will complete existing co-operation, which is not of proliferation concern, within a relatively short period. Based on significant, tangible progress with China on nuclear nonproliferation, President Clinton in 1998 took steps to bring into force the 1985 US–China Agreement on Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation.

Beijing has deployed a modest ballistic missile force, including land and sea-based intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). It was estimated in 2007 that China has about 100–160 liquid fuelled ICBMs capable of striking the United States with approximately 100–150 IRBMs able to strike Russia or Eastern Europe, as well as several hundred tactical SRBMs with ranges between 300 and 600 km.[74] Currently, the Chinese nuclear stockpile is estimated to be between 50 and 75 land and sea based ICBMs.[75]

China's nuclear program follows a doctrine of minimal deterrence, which involves having the minimum force needed to deter an aggressor from launching a first strike. The current efforts of China appear to be aimed at maintaining a survivable nuclear force by, for example, using solid-fuelled ICBMs in silos rather than liquid-fuelled missiles. China's 2006 published deterrence policy states that they will "uphold the principles of counterattack in self-defense and limited development of nuclear weapons", but "has never entered, and will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any country". It goes on to describe that China will never undertake a first strike, or use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear state or zone.[74] US strategists, however, suggest that the Chinese position may be ambiguous, and nuclear weapons may be used both to deter conventional strikes/invasions on the Chinese mainland, or as an international political tool – limiting the extent to which other nations can coerce China politically, an inherent, often inadvertent phenomenon in international relations as regards any state with nuclear capabilities.[76]

Space warfare

The PLA has deployed a number of space-based systems for military purposes, including the imagery intelligence satellite systems like the ZiYan series,[77] and the militarily designated JianBing series, synthetic aperture satellites (SAR) such as JianBing-5, BeiDou satellite navigation network, and secured communication satellites with FENGHUO-1.[78]

The PLA is responsible for the Chinese space program. To date, all the participants have been selected from members of the PLA Air Force. China became the third country in the world to have sent a man into space by its own means with the flight of Yang Liwei aboard the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft on 15 October 2003 and the flight of Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng aboard Shenzhou 6 on 12 October 2005 and Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming, and Jing Haipeng aboard Shenzhou 7 on 25 September 2008.

The PLA started the development of an anti-ballistic and anti-satellite system in the 1960s, code named Project 640, including ground-based lasers and anti-satellite missiles. On 11 January 2007, China conducted a successful test of an anti-satellite missile, with an SC-19 class KKV.[79] Its anti ballistic missile test was also successful.

The PLA has tested two types of hypersonic space vehicles, the Shenglong Spaceplane and a new one built by Chengdu Aircraft Corporation. Only a few pictures have appeared since it was revealed in late 2007. Earlier, images of the High-enthalpy Shock Waves Laboratory wind tunnel of the CAS Key Laboratory of high-temperature gas dynamics (LHD) were published in the Chinese media. Tests with speeds up to Mach 20 were reached around 2001.[80] [81]

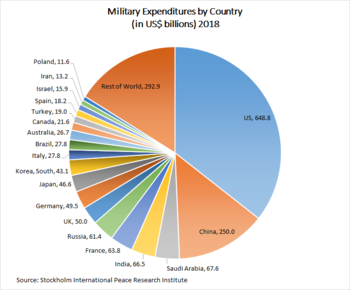

Military budget

Military spending for the People's Liberation Army has grown about 10 percent annually over the last 15 years.[82] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI, estimated China's military expenditure for 2013 to US$188.5bn.[83] China's military budget for 2014 according to IHS Jane's, a defence industry consulting and analysis company, will be US$148bn,[84] which is the second largest in the world. The United States military budget for 2014 in comparison, is US$574.9bn,[85] which is down from a high of US$664.3bn in 2012. According to SIPRI, China became the world's third largest exporter of major arms in 2010–2014, an increase of 143 per cent from the period 2005–2009. China supplied major arms to 35 states in 2010–2014. A significant percentage (just over 68 per cent) of Chinese exports went to three countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. China also exported major arms to 18 African states. Examples of China's increasing global presence as an arms supplier in 2010–2014 included deals with Venezuela for armoured vehicles and transport and trainer aircraft, with Algeria for three frigates, with Indonesia for the supply of hundreds of anti-ship missiles and with Nigeria for the supply of a number of unmanned combat aerial vehicles. Following rapid advances in its domestic arms industry, China has become less dependent on arms imports, which decreased by 42 per cent between 2005–2009 and 2010–2014.[63] China's rise in military spending come at a time when there are tensions along the South China Sea with territorial disputes involving the Philippines, Vietnam, and Taiwan, as well as escalating tensions between China and Japan involving the disputed Diaoyu (Chinese spelling) and Senkaku (Japanese spelling) islands. Former-United States Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has urged China to be more transparent about its military capabilities and intentions.[86][87] The years 2018 and 2019 both saw significant budget increases as well. China announced 2018's budget as 1.11 trillion yuan (US$165.5bn), an 8.1% increase on 2017, and 2019's budget as 1.19 trillion yuan (US$177.61bn), an increase of 7.5 per cent on 2018.[88][89]

Military spending

- March 2000: The budget was announced to be $14.6 billion[90]

- March 2001: The budget was announced to be $17.0 billion[90]

- March 2002: The budget was announced to be $20.0 billion[90]

- March 2003: The budget was announced to be $22.0 billion[90]

- March 2004: The budget was announced to be $24.6 billion[90]

- March 2005: The budget was announced to be $29.9 billion[90]

- March 2006: The budget was announced to be $35.0 billion[90]

- March 2007: The budget was announced to be $44.9 billion[91]

- March 2008: The budget was announced to be $58.8 billion[92]

- March 2009: The budget was announced to be $70.0 billion[93]

- March 2010: The budget was announced to be $76.5 billion[94]

- March 2011: The budget was announced to be $90.2 billion[94]

- March 2012: The budget was announced to be $103.1 billion[94]

- March 2013: The budget was announced to be $116.2 billion[94]

- March 2014: The budget was announced to be $131.2 billion[94]

- March 2015: The budget was announced to be $142.4 billion[94]

- March 2016: The budget was announced to be $143.7 billion[94]

- March 2017: The budget was announced to be $151.4 billion[94]

- March 2018: The budget was announced to be $165.5 billion[95]

- March 2019: The budget was announced to be $177.6 billion[96]

- May 2020: Two Sessions gathering delayed until 22 May because of coronavirus pandemic.[97]

Commercial interests

Historical

Until the mid-1990s the PLA had extensive commercial enterprise holdings in non-military areas, particularly real estate. Almost all of these holdings were supposedly spun off in the mid-1990s. In most cases, the management of the companies remained unchanged, with the PLA officers running the companies simply retiring from the PLA to run the newly formed private holding companies.[98]

The history of PLA involvement in commercial enterprises began in the 1950s and 1960s. Because of the socialist state-owned system and from a desire for military self-sufficiency, the PLA created a network of enterprises such as farms, guest houses, and factories intended to financially support its own needs. One unintended side effect of the Deng-era economic reforms was that many of these enterprises became very profitable. For example, a military guest house intended for soldier recreation could be easily converted into a profitable hotel for civilian use. There were two main factors which increased PLA commercial involvement in the 1990s. One was that running profitable companies decreased the need for the state to fund the military from the government budget. The second was that in an environment where legal rules were unclear and political connections were important, PLA influence was very useful.

By the early 1990s party officials and high military officials were becoming increasingly alarmed at the military's commercial involvement for a number of reasons. The military's involvement in commerce was seen to adversely affect military readiness and spread corruption. Further, there was great concern that having an independent source of funding would lead to decreased loyalty to the party. The result of this was an effort to spin off the PLA's commercial enterprises into private companies managed by former PLA officers, and to reform military procurement from a system in which the PLA directly controls its sources of supply to a contracting system more akin to those of Western countries. The separation of the PLA from its commercial interests was largely complete by the year 2000. It was met with very little resistance, as the spinoff was arranged in such a way that few lost out.[98]

Contemporary

The rapidly expanding CEFC China Energy, that in October 2017 bought a $9 billion stake in Russia's largest oil producer Rosneft,[99] is linked to the PLA.[100][101]

In June 2020, the Trump administration determined that twenty Chinese firms "are owned or controlled" by the PLA. The firms have been enumerated under a 1999 law which mandates that a list be kept of PLA firms which "provide commercial services, manufacture, produce or export". As such the firms, some of which are listed on stock exchanges, are liable to be sanctioned by the US and include:[102]

- Huawei

- Hikvision

- China Mobile Communications

- China Telecommunications Corporation

- Aviation Industry Corporation of China

Anthem and insignia

The military anthem of the PLA is the Military Anthem of the People's Liberation Army (simplified Chinese: 中国人民解放军军歌; traditional Chinese: 中國人民解放軍軍歌; pinyin: Zhōngguó Rénmín Jiěfàngjūn Jūngē). The Central Military Commission adopted the song on 25 July 1988. The lyrics of the anthem were written by Gong Mu and the music was composed by Zheng Lücheng.

The PLA's insignia consists of a roundel with a red star bearing the Chinese characters for Eight One, referring to the Nanchang uprising which began on 1 August 1927.

See also

- 2015 People's Republic of China military reform

- Chinese espionage in the United States

- Chinese information operations and information warfare

- Military Power of the People's Republic of China

- Ministry of National Defense of the People's Republic of China

- National Revolutionary Army

- Ranks of the People's Liberation Army Air Force

- Ranks of the People's Liberation Army Ground Force

- Ranks of the People's Liberation Army Navy

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- Timeline of the Cox Report controversy

- Titan Rain

- Type 07

Notes

References

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (15 February 2019). The Military Balance 2019. London: Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 9781857439885.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "China to splash out US$175 billion on its military". 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "China boosts defence spending to $175 billion amid military modernisation". Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "How dominant is China in the global arms trade?". ChinaPower Project. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "How is China strengthening its military? - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "China News: Asia Times Online is a quality Internet-only publication that reports and examines geopolitical, political, economic and business issues. Travel Reservations". www.atimes.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Gao, Charlie (5 January 2018). "This War Turned China into a Military Superpower". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "Global military spending remains high at $1.7 trillion | SIPRI". www.sipri.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Gertz, Bill (7 November 2016). "Report: China's Military Capabilities Are Growing at a Shocking Speed". The National Interest. The National Interest. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Tan, Anjelica (25 October 2018). "To prevent war, prepare to win". The Hill. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Rose, Frank A. (23 October 2018). "As Russia and China improve their conventional military capabilities, should the US rethink its assumptions on extended nuclear deterrence?". Brookings. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- O’Sullivan, Michael; Subramanian, Krithika (17 October 2015). The End of Globalization or a more Multipolar World? (Report). Credit Suisse AG. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Li, Nan (26 February 2018). "Party Congress Reshuffle Strengthens Xi's Hold on Central Military Commission". The Jamestown Foundation . Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Xi Jinping has introduced major institutional changes to strengthen his control of the PLA in his roles as Party leader and chair of the Central Military Commission (CMC)...

- M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defense: China's Military Strategy since 1949 (2019).

- "The PLA Navy's New Historic Missions: Expanding Capabilities for a Re-emergent Maritime Power" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- Pamphlet number 30-51, Handbook on the Chinese Communist Army (PDF), Department of the Army, 7 December 1960, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011, retrieved 1 April 2011

- S. Frederick Starri (2004). S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 157. ISBN 0765613182. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- S. Frederick Starr (2004). S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 158. ISBN 0765613182. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- The Political System of the People's Republic of China. Chief Editor Pu Xingzu, Shanghai, 2005, Shanghai People's Publishing House. ISBN 7-208-05566-1, Chapter 11 The State Military System.

- News of the Communist Party of China, Hyperlink Archived 13 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- "China establishes Rocket Force and Strategic Support Force – China Military Online". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 2012-06-21, New Chinese peacekeeping force arrives in Lebanon, People's Daily

- 2012-10-20, Chinese peacekeepers to Congo (K) win medals, PLA Daily

- Daniel M. Hartnett, 2012-03-13, China's First Deployment of Combat Forces to a UN. Peacekeeping Mission—South Sudan Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission

- Bernard Yudkin Geoxavier, 2012-09-18, China as Peacekeeper: An Updated Perspective on Humanitarian Intervention Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Journal of International Affairs

- 2010-05-04, Global General Chinese peacekeepers return home from Haiti Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, China Daily

- 在弘扬古田会议精神中铸牢军魂, Zài hóngyáng gǔtián huìyì jīngshén zhōng zhù láo jūn hún Archived 2 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine PLA Daily 27 October 2014

- The Political System of the People's Republic of China. Chief Editor Pu Xingzu, Shanghai, 2005, Shanghai People's Publishing House. ISBN 7-208-05566-1 Chapter 11, the State Military System, pp. 369–392.

- John Pike. "Strict Changes Announced for China Military Brass". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "China releases guideline on military reform – Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Considerations for replacing Military Area Commands with Theater Commands". english.chinamil.com.cn. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Xi declares victory over old rivals Jiang, Hu Archived 27 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Asia Nikkei Asian Review, 11 Feb 2016

- "2.12 The military and politics," in: Sebastian Heilmann, editor, ["Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) China's Political System], Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2017) ISBN 978-1442277342

- China plans military reform to enhance its readiness Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine – The-Japan-news.com, 2 January 2014

- International Institute for Strategic Studies: The Military Balance 2018, p. 250.

- "Chinese Ground Forces". SinoDefence.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2010.