Mobilization

Mobilization, in military terminology, is the act of assembling and readying troops and supplies for war. The word mobilization was first used, in a military context, in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Imperial Russian Army.[1] Mobilization theories and tactics have continuously changed since then. The opposite of mobilization is demobilization.

Mobilization became an issue with the introduction of conscription, and the introduction of the railways in the 19th century. Mobilization institutionalized the mass levy of conscripts that was first introduced during the French Revolution, and that had changed the character of war. A number of technological and societal changes promoted the move towards a more organized way of deployment. These included the telegraph to provide rapid communication, the railways to provide rapid movement and concentration of troops, and conscription to provide a trained reserve of soldiers in case of war.

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was able to mobilize at various times between 6% (81–83 BCE) to as much as 10% (210s BCE) of the total Roman population, in emergencies and for short periods of time.[2] This included poorly-trained militia.

Modern era

The Confederate States of America is estimated to have mobilized about 11% of its free population in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[2] The Kingdom of Prussia mobilized about 6–7% of its total population in the years 1760 and 1813.[2] The Swedish Empire mobilized 7.7% in 1709.[2]

Armies in the seventeenth century possessed an average of 20,000 men.[3] A military force of this size requires around 20 tons of food per day, shelter, as well as all the necessary munitions, transportation (typically horses or mules), tools, and representative garments.[3] Without efficient transportation, mobilizing these average-sized forces was extremely costly, time-consuming, and potentially life-threatening.[3] Soldiers could traverse the terrain to get to war fronts, but they had to carry their supplies.[3] Many armies decided to forage for food;[3] however, foraging restricted movement because it is based on the presumption that the land the army moves over possesses significant agricultural production.[3]

However, due to new policies (like conscription), greater populations, and greater national wealth, the nineteenth-century army was composed of an average of 100,000 men. For example, in 1812 Bonaparte led an army of 600,000 to Moscow while feeding off plentiful agricultural products introduced by the turn of the century, such as potatoes.[4] Despite the advantages of mass armies, mobilizing forces of this magnitude took much more time than it had in the past.[5]

The Second Italian War of Independence illustrated all of the problems in modern army mobilization. Prussia began to realize the future of mobilizing mass armies when Napoleon III transported 130,000 soldiers to Italy by military railways in 1859.[5] French caravans that carried the supplies for the French and Piedmontese armies were incredibly slow, and the arms inside these caravans were sloppily organized.[6] These armies were in luck, however, in that their Austrian adversaries experienced similar problems with sluggish supply caravans (one of which apparently covered less than three miles per day).[6]

Not only did Prussia take note of the problems in transporting supplies to armies, but it also took note of the lack of communication between troops, officers, and generals. Austria's army was primarily composed of Slavs, but it contained many other ethnicities as well.[7] Austrian military instruction during peacetime utilized nine different languages, accustoming Austrian soldiers to taking orders only in their native language.[7] Conversely, in an effort to augment the efficacy of the new “precision rifle” developed by the monarchy, officers were forced to only speak German when giving orders to their men.[7] Even one Austrian officer commented at Solferino that his troops could not even comprehend the command, “Halt.”[7] This demonstrates the communicative problems that arose quickly with the advent of the mass army.

Mobilization in World War I

Intricate plans for mobilization contributed greatly to the beginning of World War I, since in 1914, under the laws and customs of warfare then observed (not to mention the desire to avoid compromising national security), general mobilization of one nation's military forces was invariably considered an act of war by that country's likely enemies.

In 1914, the United Kingdom was the only European Great Power without conscription. The other Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Italy, France, Germany and Russia) all relied on compulsory military service to supply each of their armies with the millions of men they believed they would need to win a major war. France enacted the “Three Year Law” (1913) to extend the service of conscripted soldiers to match the size of the German army, as the French population of 40 million was smaller than the German population of 65 million people.[8][9] The Anglo-German naval arms race began, sparked by the German enactment of the Second Naval Law. Each of the Great Powers could only afford to keep a fraction of these men in uniform in peacetime, the rest were reservists with limited opportunities to train. Maneuvering formations of millions of men with limited military training required intricate plans with no room for error, confusion, or discretion after mobilization began. These plans were prepared under the assumption of worst-case scenarios.

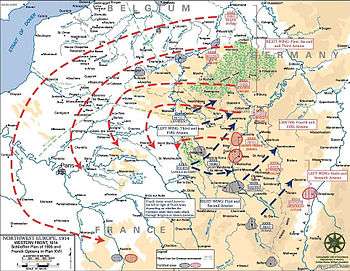

For example, German military leaders did not plan to mobilize for war with Russia whilst assuming that France would not come to her ally's aid, or vice versa. The Schlieffen Plan therefore dictated not only mobilization against both powers, but also the order of attack—France would be attacked first regardless of the diplomatic circumstances. To bypass the fortified Franco-German frontier, the German forces were to be ordered to march through Belgium. Whether or not Russia had committed the first provocation, the German plan agreed to by Emperor William II called for the attack on Russia to take place only after France was defeated.

Similarly, the Russian Stavka's war planning assumed that war against either Austria-Hungary or Germany would mean war against the other power. Although the plan allowed flexibility as to whether the main effort would be made against Germany or Austria-Hungary, in either case units would be mobilized on the frontiers of both Powers. On July 28, 1914, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (William's cousin) ordered partial mobilization against Austria-Hungary only. While war with Austria-Hungary seemed inevitable, Nicholas engaged in a personal dialogue with the German Emperor in an attempt to avoid war with Germany. However, Nicholas was advised that attempts to improvise a partial mobilization would lead to chaos and probable defeat if, as pessimists on the Russian side expected, no amount of diplomacy could convince the Germans to refrain from attacking Russia whilst she was engaged with Germany's ally. On July 29, 1914, the Tsar ordered full mobilization, then changed his mind after receiving a telegram from Kaiser Wilhelm. Partial mobilization was ordered instead.

The next day, the Tsar's foreign minister, Sergey Sazonov once more persuaded Nicholas of the need for general mobilization, and the order was issued that day, July 30. In response, Germany declared war on Russia.

Germany mobilized under von Moltke the Younger's revised version of the Schlieffen Plan, which assumed a two-front war with Russia and France. Like Russia, Germany decided to follow its two-front plans despite the one-front war. Germany declared war on France on August 3, 1914, one day after issuing an ultimatum to Belgium demanding the right of German troops to pass through as part of the planned pincer action of the military. Finally, Britain declared war on Germany for violating Belgian neutrality.

Thus the entangling alliances of the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente directed the intricate plans for mobilization. This brought all of the Great Powers of Europe into the Great War without actually utilizing the provisions of either alliance.

The mobilization was like a holiday for many of the inexperienced soldiers; for example, some Germans wore flowers in the muzzles of their rifles as they marched. Trains brought soldiers to the front lines of battle. The Germans timetabled the movements of 11,000 trains as they brought troops across the Rhine River. The French mobilized around 7,000 trains for movement. Horses were also mobilized for war. The British had 165,000 horses prepared for cavalry, the Austrians 600,000, the Germans 715,000, and the Russians over a million.[10]

Britain's Dominions including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa were compelled to go to war when Britain did. However, it was largely left up to the individual Dominions to recruit and equip forces for the war effort. Canadian, Australian and New Zealand mobilizations all involved the creation of new field forces for overseas service rather than using the existing regimental structures as a framework. In the case of Canada, the Militia Minister, Sir Sam Hughes, created the Canadian Expeditionary Force from whole cloth by sending telegrams to 226 separate reserve unit commanders asking for volunteers to muster at Valcartier in Quebec. The field force served separately from the Militia (Canada's peacetime army); in 1920 the Otter Commission was compelled to sort out which units would perpetuate the units that served in the trenches—the CEF or the prewar Militia. A unique solution of perpetuations was instituted, and mobilization during the Second World War did not repeat Sir Sam Hughes' model, which has been described by historians as being more closely akin to ancient Scottish clans assembling for battle than a modern, industrialized nation preparing for war.

"Colonials" served under British command though, perhaps owing to the limited autonomy granted to the Dominions regarding their respective mobilizations, the Dominions eventually compelled the British government to overrule the objections of some British commanders and let the Dominion forces serve together instead of being distributed amongst various British divisions. The "colonials" would go on to be acknowledged by both the British and German high commands as being elite British units. In May 1918, when command of the Australian Corps passed from William Birdwood to John Monash, it became the first British Empire formation commanded totally free of British officers.

On May 23, 1915, Italy entered World War I on the Allied side. Despite being the weakest of the big four Allied powers, the Italians soon managed to populate its army from 560 to 693 infantry battalions in 1916; the army had grown in size from 1 million to 1.5 million soldiers.[11] On August 17, 1916, Romania entered the war on the Allied side, mobilizing an army of 23 divisions. Romania was quickly defeated however by Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria. Bulgaria went so far as to ultimately mobilize 1.2 million men, more than a quarter of its population of 4.3 million people, a greater share of its population than any other country during the war.

The production of supplies gradually increased throughout the war. In Russia, the expansion of industry allowed a 2,000 percent increase in the production of artillery shells - by November 1915, over 1,512,000 artillery shells were being produced per month. In France, a massive mobilization by the female population to work in factories allowed the rate of shell production to reach 100,000 shells a day by 1915.[12]

Both sides also began drawing on larger numbers of soldiers. The British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, appealed for hundreds of thousands of soldiers, which was met with an enthusiastic response. 30 new British divisions were created. The response by volunteers allowed the British to put off the introduction of conscription until 1916. New Zealand followed suit, with Canada also eventually introducing conscription with the Military Service Act in 1917.

On April 6, 1917, the United States entered the war on the Allied side. At the entrance, the U.S. only could mobilize its army of 107,641 soldiers, ranked only seventeenth in size worldwide at the time. The United States Navy quickly mobilized, adding 5 dreadnoughts to the Allied navy. However, conscription quickly ensued. By March 1918, 318,000 U.S. soldiers had been mobilized to France. Eventually, by October 1918, a force of 2 million U.S. soldiers joined in the war effort.[13]

Mobilization in World War II

Poland partly mobilized its troops on August 24, 1939, and fully mobilized on August 30, 1939, following the increased confrontations with Germany since March 1939. On September 1, 1939 Germany invaded Poland, which prompted both France and Britain to declare war on Germany. However, they were slow to mobilize, and by the time Poland had been overrun by the Axis powers, only minor operations had been carried out by the French at the Saar River.

Canada actually carried out a partial mobilization on August 25, 1939, in anticipation of the growing diplomatic crisis. On September 1, 1939, the Canadian Active Service Force (a corps-sized force of two divisions) was mobilized even though war was not declared by Canada until September 10, 1939. Only one division went overseas in December 1939, and the government hoped to follow a "limited liability" war policy. When France was invaded in May 1940, the Canadian government realized that would not be possible and mobilized three additional divisions, beginning their overseas employment in August 1940 with the dispatch of the 2nd Canadian Division (some units of which were deployed to Iceland and Newfoundland for garrison duty before moving to the UK). Canada also enacted the National Resources Mobilization Act in 1940, which among other things compelled men to serve in the military, though conscripts mobilized under the NRMA did not serve overseas until 1944. Conscripts did, however, serve in the Aleutian Islands Campaign in 1943 though the anticipated Japanese defense never materialized due to the evacuation of the enemy garrison before the landings. Service in the Aleutians was not considered "overseas" as technically the islands were part of North America.

The United Kingdom mobilized 22% of its total population for direct military service, more than any other nation of WWII era.[14]

Economic mobilization

Economic mobilization is the preparation of resources for usage in a national emergency by carrying out changes in the organization of the national economy.[15]

It is reorganizing the functioning of the national economy to use resources most effectively in support of the total war effort. Typically, the available resources and productive capabilities of each nation determined the degree and intensity of economic mobilization. Thus, effectively mobilizing economic resources to support the war effort is a complex process, requiring superior coordination and productive capability on a national scale.[16] Importantly, some scholars have argued that such large scale mobilization of society and its resources for the purposes of warfare have the effect of aiding in state building.[17] Herbst argues that the demands of reacting to an external aggressor provides a strong enough impetus to force structural changes and also forge a common national identity.[18]

Literature

- United States Department of the Army (1955): History of Military Mobilization in the United States Army, 1775-1945 (online)

Notes

- Schubert, Frank N. "Mobilization in World War II". Permanent Access GPO Government. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Luuk de Ligt; S. J. Northwood (2008). People, Land, and Politics: Demographic Developments and the Transformation of Roman Italy 300 BC-AD 14. BRILL. pp. 38–40. ISBN 90-04-17118-5.

- Onorato, Massimiliano G., Kenneth Scheve, and David Stasavage. Technology and the Era of the Mass Army. Thesis. IMT Lucca, Stanford University, and New York University, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.politics.as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/5395/mobilization-July-2013.pdf

- Vincennes, Archive de l’Armèe de Terre (AAT), 7N848, Gaston Bodart, “Die Starkeverhaltnisse in den bedeutesten Schlachten.” Craig, The Battle of Königgrätz.

- Michael Howard, The Franco-Prussian War (1961; London: Granada, 1979), p. 23.

- Vincennes, AAT, MR 845, Anon., “Précis historique de la campagne d’Italie en 1859.” Wolf Schneider von Arno, “Der österreichisch-ungarische Generalstab,” (Kriegsarchiv Manuscript), vol. 7, pp. 18, 54, 55.

- D. N., “Über die Truppensprachen unserer Armee,” Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift (ÖMZ) 2 (1862), pp. 365-7.

- Keegan (1999)

- "Population of Germany". Tacitus.nu. 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- Keegan (1999), (footnote points to Bucholz, p. 163) pp. 73-74

- Keegan (1999), p. 275 (note also: field artillery pieces went from 1,788 to 2,068)

- Keegan (1999), pp. 275-276

- Keegan (1999), pp. 351-353, 372-374

- Alan Axelrod (2007). Encyclopedia of World War II. H W Fowler. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-8160-6022-1.

- "Economic mobilization" Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine. About.com. Accessed on May 13, 2006.

- Harrison, Mark. The Economics of World War II: Six great powers in international comparison. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Herbst, Jeffrey (Spring 1990). "War and the State in Africa". International Security. 14: 117. doi:10.2307/2538753.

- Herbst, Jeffrey. "War and the State in Africa". International Security. 14: 113. doi:10.2307/2538753.

References

- Keegan, John (1999). The First World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40052-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- State, society, and mobilization in Europe during the First World War, edited by John Horne, Cambridge-New York : Cambridge University Press, 1997.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mobilization. |