610 Office

The 610 Office is, or was, a security agency in the People's Republic of China. Named for the date of its creation on June 10, 1999,[3] it was established for the purpose of coordinating and implementing the persecution of Falun Gong.[2] Because it is a Communist Party-led office with no formal legal mandate, it is sometimes described as an extralegal organisation.[2][4] The 610 Office is the implementation arm of the Central Leading Group on Dealing with the Falun Gong (CLGDF),[5] also known as the Central Leading Group on Dealing with Heretical Religions.[2] In March, 2018, the office was reorganized and its functions delegated to the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission and the Ministry of Public Security.[6]

| 中央防范和处理邪教问题领导小组 | |

| |

The 610 Office was often overseen by high-ranking individuals in the Ministry for Public Security of the People’s Republic of China | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | June 10 1999 |

| Jurisdiction | China |

| Headquarters | Beijing |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Central Committee of the Communist Party of China[2] |

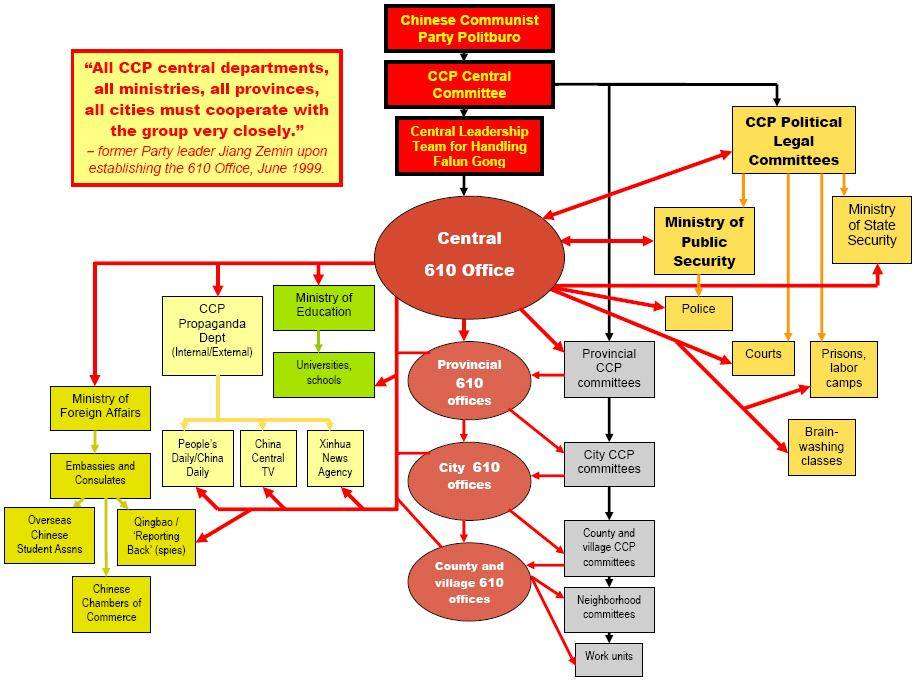

The central 610 Office has traditionally been headed by a high-ranking member of the Communist Party's Politburo Standing Committee, and it frequently directs other state and party organs in the anti-Falun Gong campaign.[2][5] It is closely associated with the powerful Political and Legislative Affairs Committee of the Communist Party of China. Local 610 Offices are also established at provincial, district, municipal and neighborhood levels, and are estimated to number approximately 1,000 across the country.[7]

The main functions of the 610 Offices include coordinating anti-Falun Gong propaganda, surveillance and intelligence collection, and the punishment and "reeducation" of Falun Gong adherents.[2][8][9] The office is reportedly involved in the extrajudicial sentencing, coercive reeducation, torture, and sometimes death of Falun Gong practitioners.[2][9]

Since 2003, the 610 Office's mission has been expanded to include targeting other religious and qigong groups deemed heretical or harmful by the Communist Party (CCP), though Falun Gong remains its main priority.[2]

Background

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a form of spiritual qigong practice that involves meditation, energy exercises, and a moral philosophy drawing on Buddhist tradition. The practice was introduced by Li Hongzhi in Northeast China in the spring of 1992, towards the end of China's "qigong boom."[10][11]

Falun Gong initially enjoyed considerable official support during the early years of its development, and amassed a following of millions. By the mid-1990s, however, Chinese authorities sought to rein in the influence of qigong practices, enacting more stringent requirements on the country’s various qigong denominations.[10] In 1996, possibly in response to the escalating pressure to formalize ties with the party-state, Falun Gong filed to withdraw from the state-run qigong association.[11] Following this severance of ties to the state, the group came under increasing criticism and surveillance from the country’s security apparatus and propaganda department. Falun Gong books were banned from further publication in July 1996, and state-run news outlets began criticizing the group as a form of "feudal superstition," whose "theistic" orientation was at odds with the official ideology and national agenda.[10]

On April 25, 1999, over 10,000 Falun Gong adherents demonstrated quietly near the Zhongnanhai government compound to request official recognition and an end to the escalating harassment against them.[12] Security czar and politburo member Luo Gan was the first to draw attention to the gathering crowd. Luo reportedly called Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin, and demanded a decisive solution to the Falun Gong problem.[5]

A group of five Falun Gong representatives presented their demands to then-Premier Zhu Rongji and, apparently satisfied with his response, the group dispersed peacefully. Jiang Zemin was reported to have been deeply angered by the event, however, and expressed concern over the fact that a number of high-ranking bureaucrats, Communist Party officials, and members of the military establishment had taken up Falun Gong.[13] That evening, Jiang disseminated a letter through Party ranks ordering that Falun Gong must be crushed.[5]

Establishment

On 7 June 1999, Jiang Zemin convened a meeting of the Politburo to address the Falun Gong issue. In the meeting, Jiang described Falun Gong as a grave threat to Communist Party authority—"something unprecedented in the country since its founding 50 years ago"[2]—and ordered the creation of a special leading group within the party's Central Committee to "get fully prepared for the work of disintegrating [Falun Gong]."[2]

On 10 June, the 610 Office was formed to handle day-to-day coordination of the anti-Falun Gong campaign. Luo Gan was selected to helm of the office, whose mission at the time was described as studying, investigating, and developing a "unified approach…to resolve the Falun Gong problem."[5] The office was not created with any legislation, and there are no provisions describing its precise mandate.[2] Nonetheless, it was authorized “to deal with central and local, party and state agencies, which were called upon to act in close coordination with that office,” according to UCLA professor James Tong.[5]

On 17 June 1999, the 610 Office came under the newly created Central Leading Group for Dealing with Falun Gong, headed by Politburo Standing Committee member Li Lanqing. Four other deputy directors of the Central Leading Group also held high-level positions in the Communist Party, including minister of the propaganda department, Ding Guangen.[5] The leaders of the 610 Office and CLGDF were "able to call on top government and party officials to work on the case and draw on their institutional resources," and had personal access to the Communist Party general secretary and the Premier.[5]

Journalist Ian Johnson, whose coverage of the crackdown on Falun Gong earned him a Pulitzer Prize, wrote that the job of the 610 Office was "to mobilize the country's pliant social organizations. Under orders from the Public Security Bureau, churches, temples, mosques, newspapers, media, courts and police all quickly lined up behind the government's simple plan: to crush Falun Gong, no measures too excessive. Within days a wave of arrests swept China. By the end of 1999, Falun Gong adherents were dying in custody.”[14]

Structure

The 610 Office is managed by top echelon leaders of the Communist Party of China, and the CLGDF that oversees the 610 Office has, since its inception, been helmed by a senior member of the Politburo Standing Committee. A list of 610 Office Chiefs, including their time in that position, includes Li Lanqing (1999–2003), Luo Gan (2003–2007), Zhou Yongkang (2007–2012), Li Dongsheng (2013), Liu Jinguo (2013-2015), Fu Zhenghua (2015-2016), and most recently Huang Ming (2016).[2]

The practice of appointing top-ranked Party authorities to run the CLGDF and 610 Office was intended to ensure that they outranked other departmental officials.[5] According to James Tong, the 610 Office is situated "several administrative strata" above organizations such as the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television, Xinhua News Agency, China Central Television, and the News and Publications Bureau. The 610 Office plays the role of coordinating the anti-Falun Gong media coverage in the state-run press, as well influencing other party and state entities, including security agencies, in the anti-Falun Gong campaign.[2][5]

Cook and Lemish speculate that the 610 Office was created outside the traditional state-based security system for several reasons: first, a number of officials within the military and security agencies were practicing Falun Gong, leading Jiang and other CPC leaders to fear that these organizations had already been quietly compromised; second, there was a need for a nimble and powerful organization to coordinate the anti-Falun Gong campaign; third, the creation of a top-level party organization sent a message down the ranks that the anti-Falun Gong campaign was a priority; and finally, CPC leaders did not want the anti-Falun Gong campaign to be hindered by legal or bureaucratic restrictions, and thus established the 610 Office extrajudicially.[2]

Soon after the creation of the central 610 Office, parallel 610 Offices were established at each administrative level wherever populations of Falun Gong practitioners were present, including the provincial, district, municipal, and sometime neighborhood levels. In some instances, 610 Offices have been established within large corporations and universities.[5] Each office takes orders from the 610 Office one administrative level above, or from the Communist Party authorities at the same organizational level.[7] In turn, the local 610 Offices influence the officers of other state and party bodies, such as media organizations, local public security bureaus, and courts.[2][7]

The structure of the 610 Office overlaps with the Communist Party’s Political and Legislative Affairs Committee (PLAC). Both Luo Gan and Zhou Yongkang oversaw both the PLC and the 610 Office simultaneously. This overlap is also reflected at local levels, where the 610 Office is regularly aligned with the local PLAC, sometimes even sharing physical offices.[2]

The individual 610 Offices at local levels show minor variations in organizational structure.[5] One example of how local offices are organized comes from Leiyang city in Hunan province. There, the 610 Office consisted in 2008 of a "composite group" and an "education group." The education group was in charge of "propaganda work" and the "transformation through reeducation" of Falun Gong adherents. The composite group was in charge of administrative and logistics tasks, intelligence collection, and the protection of confidential information.[9]

James Tong wrote that the Party's decision to run the anti-Falun Gong campaign through the CLGDF and the 610 Office reflected "a pattern of regime institutional choice" to use "ad hoc committees rather than permanent agencies, and invested power in the top party echelon rather than functional state bureaucracies."[5]

Recruitment

Relatively little is known about recruiting processes for local 610 Offices. In rare instances where such information is available, 610 officers appeared to have been drawn from other party or state agencies (such as the Political and Legislative Committee staff or Public Security Bureaus).[5] Hao Fengjun, a defector and former officer with the 610 Office in Tianjin City, was one such officer. Hao had previously worked for the Public Security Bureau in Tianjin, and was among the officers selected to be seconded to the newly created 610 Office. According to Hao, few officers volunteered for a position in the 610 Office, so selections were made through a random draw.[15] Some 610 Offices conduct their own recruiting efforts to bring in staff with university degrees.[5]

Responsibility system

In order to ensure compliance with the Party's directives against Falun Gong, the 610 offices implemented a responsibility system that extended down to the grassroots levels of society. Under this system, the local officials were held accountable for all Falun Gong-related outcomes under their jurisdiction, and a system of punitive fines were imposed on regions and officials who failed to adequately persecute Falun Gong.[5][14] "This showed that, instead of creating a modern system to rule China, the government still relied on an ad hoc patchwork of edicts, orders and personal connections," wrote Johnson.[14]

An example of this responsibility system was shown in the handling of protesters traveling to Beijing in the early years of the persecution. After the persecution of Falun Gong began in 1999, hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners traveled daily to Tiananmen Square or to petitioning offices in Beijing to appeal for their rights. In order to stem the flow of protesters in the capital, the central 610 Office held local authorities responsible for ensuring that no one from their region went to Beijing. "The provincial government fined mayors and heads of counties for each Falun Gong practitioner from their district who went to Beijing," wrote Johnson. The mayors and county leaders then fined the heads of their local 610 offices or PLAC branches, who in turn fined the village chiefs, who fined the police. The police administered punishment to the Falun Gong practitioners, and regularly demanded money from them to recoup the costs.[14] Johnson wrote that "The fines were illegal; no law or regulation has ever been issued in writing that lists them." Government officials announced them only orally in meetings. "There was never to be anything in writing because they didn't want it made public," one official told Johnson.[14]

Functions

Surveillance and intelligence

Surveillance of Falun Gong practitioners and intelligence collection is among the chief functions of 610 Offices. At the local levels, this involves monitoring workplaces and residences to identify Falun Gong practitioners, making daily visits to the homes of known (or "registered") Falun Gong practitioners, or coordinating and overseeing 24-hour monitoring of practitioners.[5][8] The 610 Office does not necessarily conduct the surveillance directly; instead, it orders local authorities to do so, and has them report at regular intervals to the 610 Office.[5] Basic-level 610 Offices relay the intelligence they have collected up the operational chain to the 610 Office above them.[7] In many instances, the surveillance is targeted towards Falun Gong practitioners who had previously recanted the practice while in prison or labor camps, and is intended to prevent "recidivism."[8]

The 610 Office's intelligence collection efforts are bolstered through he cultivation of paid civilian informants. 610 Offices at local levels have been found to offer substantial monetary rewards for information leading to the capture of Falun Gong practitioners, and 24-hour hotlines have been created for civilians to report on Falun Gong-related activity.[9] In some locales, 'responsibility measures' are enacted whereby workplaces, schools, neighborhood committees and families are held accountable for monitoring and reporting on Falun Gong practitioners within their ranks.[8]

In addition to domestic surveillance, the 610 Office is allegedly involved in foreign intelligence. Hao Fengjun, the former 610 officer-turned defector from Tianjin, testified that his job at the 610 Office involved collating and analyzing intelligence reports on overseas Falun Gong populations, including in the United States, Canada and Australia.[16]

In 2005, a Chinese agent working with the Chinese embassy in Berlin recruited a German Falun Gong practitioner Dr. Dan Sun to act as an informant.[17] The agent reportedly arranged a meeting for Sun with two men who purported to be scholars of Chinese medicine interested in researching Falun Gong, and Sun agreed to pass information to them, ostensibly hoping to further their understanding of the practice. The men were in fact high-ranking agents of the 610 Office in Shanghai. Sun maintained that he had no knowledge the men he was corresponding with were Chinese intelligence agents, but because he cooperated with them, he was nonetheless convicted of espionage in 2011.[18] According to Der Spiegel, the case demonstrated "how important fighting [Falun Gong] is to the [Chinese] government," and "points to the extremely offensive approach that is sometimes being taken by the Chinese intelligence agencies."[17]

Propaganda

Propaganda is among the core functions of the 610 Office, both at the central and local levels.[5][8] The CLGDF includes high-ranking members of the Communist Party's propaganda department, including the minister of propaganda and deputy head of the Central Leading Group on Propaganda and Ideological Work. This, coupled with the 610 Office's organizational position above the main news and propaganda organs, gives it sufficient influence to direct the anti-Falun Gong propaganda efforts at the central level.[5]

Tong notes that the first "propaganda assaults" on the Falun Gong were launched in the leading state-run newspapers in late June, 1999—shortly after the establishment of the 610 office, but before the campaign against Falun Gong had been officially announced. The effort was overseen by Ding Guangen in his capacity as the deputy leader of the Central Leading Group for Dealing with Falun Gong and the country's propaganda chief. The initial media attacks contained only veiled, indirect references to Falun Gong, and their content aimed to deride "superstition" and extol the virtues of atheism.[5] In the weeks leading up to the official launch of the campaign, the CLGDF and the 610 Office set to work preparing a large number of books, editorials, and television programs denouncing the group, which were made public after 20 July 1999 when the campaign against Falun Gong officially began.[5]

In the months following July 1999, David Ownby writes that the country's media apparatus "was churning out hundreds of articles, books, and television reports against Falun Gong. The Chinese public had not witnessed such overkill since the heyday of the Cultural Revolution."[19] State propaganda initially used the appeal of scientific rationalism to argue that Falun Gong's worldview was in "complete opposition to science" and communism;[20] the People's Daily asserted on 27 July 1999, that it "was a struggle between theism and atheism, superstition and science, idealism and materialism." Other rhetoric appearing in the state-run press centered on charges that Falun Gong had misled followers and was dangerous to health. To make the propaganda more accessible to the masses, the government published comic books, some of which compared Falun Gong’s founder to Lin Biao and Adolf Hitler.[21]

The Central 610 Office also directs local 610 Offices to carry out propaganda work against Falun Gong. This includes working with local media, as well as conducting grassroots campaigns to "educate" target audiences in schools and universities, state-run enterprises, and social and commercial enterprises.[8][9] In 2008, for instance, the central 610 Office issued a directive to engage in propaganda work intended to prevent Falun Gong from "interfering with" the Beijing Olympics.[8] The campaign was referenced on government web sites in every Chinese province.[8]

Reeducation and detention

610 Offices work with local security agencies to monitor and capture Falun Gong adherents, many of whom are then sentenced administratively to reeducation-through-labor camps (RTL), or, if they continue to practice and advocate for Falun Gong, sentenced to prison.[8] The number of Falun Gong adherents detained in China is estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands; in some facilities, Falun Gong practitioners are in the majority.[8][23]

610 Offices throughout China maintain an informal network of "transformation-through-reeducation" facilities. These facilities are used specifically for ideological reprogramming of Falun Gong practitioners, whereby they are subjected to physical and mental coercion in an effort to have them renounce Falun Gong.[8] In 2001, the central 610 Office began ordering "all neighborhood committees, state institutions and companies" to begin using the transformation facilities. No Falun Gong practitioners were to be spared, including students and the elderly.[24] The same year, the 610 Office reportedly relayed orders that those who actively practice Falun Gong must be sent to prisons or labor camps, and those who did not renounce their belief in Falun Gong were to be socially isolated and monitored by families and employers.[25]

In 2010, the central 610 Office initiated a three-year campaign to intensify the "transformation" of known Falun Gong practitioners. Documents from local 610 Offices across the country revealed the details of the campaign, which involved setting transformation quotas, and required local authorities to forcefully take Falun Gong practitioners into transformation-through-reeducation sessions. If they failed to recant their practice, the practitioners would be sent to labor camps.[4]

In addition to prisons, labor camps and transformation facilities, the 610 Office can arbitrarily compel mentally healthy Falun Gong practitioners into psychiatric facilities. In 2002, it was estimated that approximately 1,000 Falun Gong adherents were being held against their will in mental hospitals, where reports of abuse were common.[26]

Interference in legal system

The majority of detained Falun Gong practitioners are sentenced administratively to reeducation-through-labor camps, though several thousand have been condemned to longer sentences in prisons. Chinese human rights lawyers have charged that the 610 Office regularly interferes with legal cases involving Falun Gong practitioners, subverting the ability of judges to adjudicate independently.[2][9] Attorney Jiang Tianyong has noted that cases where the defendants are Falun Gong practitioners are decided by the local 610 Offices, rather than through recourse to legal standards.[2] In November 2008, two lawyers seeking to represent Falun Gong practitioners in Heilongjiang noted that the presiding judge in the case was seen meeting with 610 Office agents.[9] Other lawyers, including Gao Zhisheng, Guo Guoting and Wang Yajun have alleged that the 610 Office interfered with their ability to meet with Falun Gong clients or defend them in court.[2][27]

Official documents support the allegation of interference by the 610 Office. In 2009, two separate documents from Jilin province and Liaoning Province described how legal cases against Falun Gong practitioners must be approved and/or audited by the 610 Office.[9] The 610 Office's organizational proximity to the CPC's Political and Judicial Committee better enables it to exercise influence with the Supreme People's Court and Ministry of Justice, both at the central level and with their counterparts at local levels.[7]

Allegations of torture and killing

Several sources have reported 610 officers as being involved in or ordering the torture of Falun Gong adherents in custody. In a letter to Chinese leaders in 2005, prominent human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng relayed accounts of 610 officers beating and sexually assaulting Falun Gong practitioners: “of all the true accounts of incredible violence that I have heard, of all the records of the government’s inhuman torture of its own people, what has shaken me most is the routine practice on the part of the 6–10 Office and the police of assaulting women’s genitals,” wrote Gao.[8][28] Defector Hao Fengjun described witnessing one of his 610 Office colleagues beating an elderly female Falun Gong practitioner with an iron bar. The event helped catalyze Hao's decision to defect to Australia.[15][29] The 2009 report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings relayed allegations that the 610 Office was involved in the torture deaths of Falun Gong practitioners ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.[30]

Ian Johnson of the Wall Street Journal reported in 2000 that Falun Gong practitioners were tortured to death in "transformation-through-reeducation" facilities that are run by the 610 Office. The central 610 Office had informed local authorities that they could use any means necessary to prevent Falun Gong practitioners from traveling to Beijing to protest the ban—an order that reportedly resulted in widespread abuse in custody.[31][32]

Expanded functions

In 2003, the name of the Central Leading Group for Dealing with Falun Gong was changed to the "Central Leading Group on Dealing with Heretical Religions." The same year, its mandate was expanded to include disposing of 28 other "heretical religions" and "harmful qigong practices".[2] Although Falun Gong continues to be the 610 Office's primary concern, there is evidence of local offices targeting members of other groups, some of which identify as Buddhist or Protestant denominations. This include carrying out surveillance against members, engaging in propaganda efforts, and detaining and imprisoning members.[9]

The Economist reported that 610 officers were involved in enforcing the house arrest of Chen Guangcheng, a blind human rights activist, that generated controversy as the police chief faced repercussions.[33]

In 2008, a new set of "leading groups" appeared with the mandate of "maintaining stability." Corresponding local offices were established in every district in major coastal cities, being tasked with "ferreting out" anti-Communist Party elements.[34] The branch offices for Maintaining Stability overlap significantly with local 610 Offices, sometimes sharing offices, staff, and leadership.[2]

Cook and Lemish write that the increased reliance on ad hoc committees such as the 610 Office and stability maintenance offices may indicate a sense among Communist Party leaders that the existing state security services are ineffective in meeting its needs. "That these officials are increasingly relying on more arbitrary, extra-legal, and personalized security forces to protect their hold on power does not only bode badly for China's human rights record. It also threatens the stability of internal CCP politics should 610 Office work become politicized," they write.[2]

Reorganization or Demise in 2018

On March 19, 2018, by publishing a document dated March 21, it was announced that the 610 Office was being abolished and its functions transferred to the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission and the Ministry of Public Security.[35] Hong Kong scholar Edward Irons reported in February 2019 that what had been "abolished" was the Central 610 Office, while local offices remained active. The scholar also noticed that the reorganization strengthened, rather than softening, the repression of banned religious groups, and that another structure within the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Public Security Anti-Xie-Jiao Bureau (公安部反邪教局: xiejiao is a term often translated as "cults" or "evil cults" but Irons and other scholars prefer the translation "heterodox teachings"[36]), which was always parallel but separated from the 610 Office, also continues its independent activities.[37]

References

- Ong, Larry (8 July 2016). "Inspection of 'Chinese Gestapo' Begins With Unusual Announcement". Epoch Times. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Cook, Sarah; Lemish, Leeshai (November 2011). "The 610 Office:Policing the Chinese Spirit". China Brief. 11 (17). Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Spiegel, Mickey (2002). Dangerous Meditation: China's Campaign Against Falungong. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-270-X. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ‘Communist Party Calls for Increased Efforts To "Transform" Falun Gong Practitioners as Part of Three-Year Campaign’ Archived 2011-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. Congressional Executive Commission on China. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Tong, James (2009). Revenge of the Forbidden City: The Suppression of Falungong in China, 1999-2005. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195377286.

- "中共中央印发《深化党和国家机构改革方案》". Xinhuanet. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018.

- Xia, Yiyang (June 2011). "The illegality of China's Falun Gong crackdown—and today's rule of law repercussions" (PDF). European Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ‘Annual Report 2008’ Archived 2014-12-07 at the Wayback Machine. Congressional-Executive Commission on China. 31 October 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Annual Report 2009". Congressional-Executive Commission on China. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Ownby, David (2008). Falun Gong and the Future of China. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532905-6. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

Falun Gong and the Future of China.

- Palmer, David (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science and Utopia in China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14066-9. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

Qigong Fever: Body, Science and Utopia in China.

- Gutmann, Ethan (13 July 2009). "An Occurrence on Fuyou Street" Archived 2013-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. National Review. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Jiang Zemin, "Letter to Party cadres on the evening of April 25, 1999" republished in Beijing Zhichun (Beijing Spring) no. 97, June 2001.

- Johnson, Ian (2004). Wild Grass: Three Portraits of Change in Modern China. New York, NY: Vintage. pp. 251–252, 283–287. ISBN 0375719199.

- Hao, Fengjun (10 June 2005). "Hao Fengjun: Why I Escaped from China (Part II)" Archived 2007-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, The Epoch Times. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Hughes, Gary; Allard, Tom (9 June 2005). "Fresh from the Secret Force, a spy downloads on China" Archived 2012-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Röbel, Sven; Stark, Holger (30 June 2010)."A Chapter from the Cold War Reopens: Espionage Probe Casts Shadow on Ties with China" Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine, Speigel International. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Matthew Robertson, Matthew; Tian, Yu (12 June 2011). "Man Convicted of Spying on Falun Gong in Germany" Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. The Epoch Times. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Ownby, David (2007). 'Qigong, Falun Gong, and the Body Politic in Contemporary China,' in China's transformations: the stories beyond the headlines. Lionel M. Jensen, Timothy B. Weston ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-3863-X.

- Lu, Xing Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: the impact on Chinese thought, culture, and communication, University of South Carolina Press (2004).

- Faison, Seth (17 August 1999). “If it’s a Comic Book, Why is Nobody Laughing?” Archived 2013-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-02-10. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Davis, Sara; Goettig, Mike; C. Christine (December 2005). We Could Disappear at Any Time: Retaliation and Abuses against Chinese Petitioners. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- Pomfret, John; Pan, Philip (5 August 2001). "Torture is Breaking Falun Gong:China Systematically Eradicating Group". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Hutzler, Charles (26 April 2001). "Falun Gong Feels Effect of China's Tighter Grip." The Asian Wall Street Journal.

- Lu, Sunny Y.; Galli, Viviana B. "Psychiatric abuse of Falun Gong practitioners in China." Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law 30:126-30, (2002).

- “China: Lawyer Barred from Representing Client by ‘6-10’ Agents” Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. Human Rights in China. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Gao, Zhisheng (2007). A China More Just Archived 2019-05-02 at the Wayback Machine. Broad Press. ISBN 1932674365.

- Gutmann, Ethan (May/June 2010). "Hacker Nation: China’s Cyber Assault" Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. World Affairs Journal.

- Alston, Philip. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions” Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, 29 May 29.

- Johnson, Ian (26 December 2000). "Death Trap: How One Chinese City Resorted to Atrocities to Control Falun Dafa" Archived 2012-04-06 at the Wayback Machine. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Bryan Edelman and James T. Richardson. "Falun Gong and the Law: Development of Legal Social Control in China." Nova Religio 6.2 (2003), 325.

- "Guarding the guardians: The party makes sure that the people who guarantee its rule are themselves under tight control". The Economist. 30 June 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Lam, Willy (9 December 2009)."China’s New Security State" Archived 2017-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal, Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- See the document reproduced in Boxun Blog, 中央 610职责划归中央政法委公安部 加强和改进新时代反邪教工作 Archived 2019-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, March 21, 2018.

- Penny, Benjamin (2012). The Religion of Falun Gong. University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-226-65501-7. Archived from the original on 2019-04-25. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- Edward Irons, Major Changes in the Structures for Fighting Xie Jiao in China Archived 2019-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, Bitter Winter, 24 February 2019.