Exercise RIMPAC

RIMPAC, the Rim of the Pacific Exercise, is the world's largest international maritime warfare exercise. RIMPAC is held biennially during June and July of even-numbered years from Honolulu, Hawaii. It is hosted and administered by the United States Navy's Indo-Pacific Command, headquartered at Pearl Harbor, in conjunction with the Marine Corps, the Coast Guard, and Hawaii National Guard forces under the control of the Governor of Hawaii. The US invites military forces from the Pacific Rim and beyond to participate. With RIMPAC the United States Indo-Pacific Command seeks to enhance interoperability among Pacific Rim armed forces, as a means of promoting stability in the region to the benefit of all participating nations. It is described by the US Navy as a unique training opportunity that helps participants foster and sustain the cooperative relationships that are critical to ensuring the safety of sea lanes and security on the world's oceans.[1]

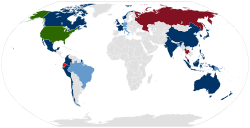

Exercise RIMPAC 2014 | |

|---|---|

Map Legend

| |

| Headquarters | Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, U.S |

| Type | Military exercises |

| Members | 22 Participants

(RIMPAC 2014)

6 Observers

(RIMPAC 2014)

2 Past Active

(Not active in 2014)

2 Past Observers

(Not observing in 2014)

|

| Establishment | 1971 |

Participants

The first RIMPAC, held in 1971, involved forces from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US). Australia, Canada, and the US have participated in every RIMPAC since then. Other regular participants are Chile, Colombia, France, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Peru, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand. The Royal New Zealand Navy was frequently involved until the 1985 ANZUS nuclear ships dispute, but has taken part in recent RIMPACs such as in 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018.

Several observer nations are usually invited, including China, Ecuador, India, Mexico, the Philippines, and Russia, who became an active participant for the first time in 2012.[2] While not contributing any ships, observer nations are involved in RIMPAC at the strategic level and use the opportunity to prepare for possible full participation in the future.

The United States contingent has included an aircraft carrier strike group, submarines, up to a hundred aircraft and 20,000 Sailors, Marines, Coast Guardsmen and their respective officers. The size of the exercises varies from year to year.

RIMPAC 2004

| RIMPAC 2004 Participating Ships[3] | |

|---|---|

| HMAS Newcastle HMAS Parramatta HMAS Success | |

| HMCS Algonquin HMCS Regina HMCS Protecteur HMCS Brandon | |

| Almirante Lynch | |

| USS John C. Stennis USS Lake Champlain USS Howard USS Ford USNS Rainier USS Tarawa USS Rushmore USS Dubuque USS Lake Erie USS Paul Hamilton USS O'Kane Cape Girardeau (C-5-S-75a class) USCGC Rush USS Chosin USNS Walter S. Diehl USS Avenger USS Defender HSV-2 Swift USNS Victorious USNS Effective USS John Paul Jones | |

| RIMPAC 2004 Participating Submarines[4] | |

|---|---|

| HMAS Rankin | |

| Simpson (Type 209) | |

| JDS Narushio (Oyashio class) | |

| ROKS Chang Bogo | |

| USS Olympia USS Key West USS Louisville | |

RIMPAC 2004 included 40 ships, seven submarines, 100 aircraft, and nearly 18,000 military personnel from seven navies, including Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, Chile, and the United Kingdom.[3][4][5][6] It focused on multinational training while building trust and cooperation among the participating naval partners. Rear Admiral Patrick M. Walsh, Commander Carrier Group Seven, served as Multinational Task Force Commander[7] aboard the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis.

RIMPAC 2008

RIMPAC 2008 included 35 ships, seven submarines, 150 aircraft, and nearly 20,000 military personnel from Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Netherlands, Peru, Republic of Korea, Singapore, United Kingdom and the United States while India, Colombia, Mexico, and Russia sent staffs only.[8] The USS Kitty Hawk was the main aircraft carrier during the exercise.

| RIMPAC 2004 Participating Ships[3] | |

|---|---|

|

HMAS Anzac (FFH 150) | |

|

BAP Quiñones (FM-58) | |

|

JS Makinami (DD-112) | |

| USS Kitty Hawk USS Lake Erie USS Port Royal USS Bonhomme Richard USS Rodney M. Davis USS Comstock USS Chung-Hoon USS Pinckney USS Paul Hamilton USS O'Kane Reuben James USCGC Rush USCGC Kiska USS Milius USNS Salvor SS Cape Gibson (AK-5051) USNS Guadalupe (T-AO-200) USNS Sumner USNS Able USNS Sioux USNS Navajo USNS Yukon | |

| RIMPAC 2004 Participating Submarines[4] | |

|---|---|

| HMAS Rankin | |

| Simpson (Type 209) | |

| JDS Narushio (Oyashio class) | |

| ROKS Chang Bogo | |

| USS Olympia USS Key West USS Louisville | |

RIMPAC 2010

_transits_the_Pacific_Ocean_with_ships_assigned_to_Rim_of_the_Pacific_(RIMPAC)_2010_combined_task_force_as_part_of_a_photo_exercise_north_of_Hawaii.jpg)

On 23 June 2010, U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Patrick M. Walsh and Combined Task Force commander Vice Admiral Richard W. Hunt announced the official start of the month-long 2010 Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise during a press conference held in Lockwood Hall at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. RIMPAC 2010 was the 22nd exercise in the series that originated in 1971.[9] The exercise was designed to increase the operational and tactical proficiency of participating units in a wide array of maritime operations by enhancing military-to-military relations and interoperability.[10] Thirty-two ships, five submarines, over 170 aircraft, and 20,000 personnel participated in RIMPAC 2010, the world's largest multi-national maritime exercise.[11]

RIMPAC 2010 brought together units and personnel from Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Netherlands, Peru, South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and the United States. During the exercise, participating countries conducted gunnery, missile, anti-submarine, and air defense exercises, as well as maritime interdiction and vessel boarding, explosive ordnance disposal, diving and salvage operations, mine clearance operations, and an amphibious landing. RIMPAC 2010 will also emphasize littoral operations with ships like the U.S. littoral combat ship Freedom, the French frigate Prairial, and the Singaporean Formidable-class frigate RSS Supreme.[9]

On 28 June 2010, the aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan arrived in Pearl Harbor to participate in RIMPAC 2010. Ronald Reagan was the only aircraft carrier to participate in this exercise. During the in-port phase of RIMPAC, officers and crew of the 14 participating navies interact in receptions, meetings, and athletic events.[12] Ronald Reagan completed its Tailored Ships Training Availability (TSTA) exercises prior to RIMPAC 2010.[12]

During 6–7 July 2010, 32 naval vessels and five submarines from seven nations departed Pearl Harbor to participate in Phase II of RIMPAC 2010. This phase included live fire gunnery and missile exercises; maritime interdiction and vessel boardings; and anti-surface warfare, undersea warfare, naval maneuvers and air defense exercises. Participants also collaborated in explosive ordnance disposal; diving and salvage operations; mine clearance operations; and amphibious operations.[13] Phase III involved scenario-driven exercises designed to further strengthen maritime skills and capabilities.[13]

During RIMPAC 2010, over 40 naval personnel from Singapore, Japan, Australia, Chile, Peru, and Colombia managed combat exercises while serving aboard Ronald Reagan (pictured). This involved managing anti-submarine warfare and surface warfare for Carrier Strike Group Seven and the entire RIMPAC force, including the use of radar, charts, and high-tech devices to monitor, chart, and communicate with other ships and submarines. Tactical action officers from the different countries coordinated the overall operational picture and provided direction and administration to the enlisted personnel involved in the Sea Combat Control (SCC) activities.[14] Also, Ronald Reagan conducted a live Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM) launch, firing at a simulated target, the first since 2007.[11][12]

On 30 July 2010, RIMPAC 2010 concluded with a press conference held at Merry Point Landing on Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam.[10] A reception for over 1,500 participants, distinguished visitors and special guests was held in the hangar bays of the carrier Ronald Reagan.[11]

During RIMPAC 2010, participating countries conducted three sinking exercises (SINKEX) involving 140 discrete live-fire events that included 30 surface-to-air engagements, 40 air-to-air missile engagements, 12 surface-to-surface engagements, 76 laser-guided bombs, and more than 1,000 rounds of naval gunfire from 20 surface combatant warships.[10] Units flew more than 3100 air sorties, completed numerous maritime interdiction and vessel boardings, explosive ordnance disposal, diving and salvage operations and mine clearance operations and 10 major experiments, with the major one being the U.S. Marine Corps Enhanced Company Operations experiment.[10] Ground forces from five countries completed five amphibious landings, including nine helicopter-borne amphibious landings and 560 troops from ship-to-shore mission. In all, 960 different training events were scheduled and 96 percent were completed in all areas of the Hawaiian operations area, encompassing Kāneʻohe Bay, Bellows Air Force Station, the Pacific Missile Range Facility, and the Pohakuloa Training Area.[10]

RIMPAC 2012

RIMPAC 2012 is the 23rd exercise in the series and started on 29 June 2012. 42 ships, including the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz and other elements of Carrier Strike Group 11, six submarines,[15] 200 aircraft and 25,000 personnel from 22 nations took part in Hawaii. The exercise involved surface combatants from the U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, South Korea and Chile.[16] The US Navy demonstrated its 'Great Green Fleet' of biofuel-driven vessels for which it purchased 450,000 gallons of biofuel, the largest single purchase of biofuel in history at a cost of $12m.[17] On 17 July, USNS Henry J. Kaiser delivered 900,000 gallons of biofuel and traditional petroleum-based fuel to Nimitz's Carrier Strike Group 11.[18]

The exercises included units or personnel from Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, the Republic of Korea, the Republic of the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, Tonga, the United Kingdom and the United States.[19][20] Russia participated actively for the first time,[2] as did the Philippines, reportedly due to the escalating tensions with the People's Republic of China over ownership of Scarborough Shoal.[21]

RIMPAC 2012 marked the debut of the U.S. Navy's new P-8A Poseidon land-based anti-submarine patrol aircraft, with two P-8As participating in 24 RIMPAC exercise scenarios as part of Air Test and Evaluation Squadron One (VX-1) based at Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kaneohe Bay.[22]

RIMPAC 2014

| RIMPAC 2014 Observers |

|---|

| RIMPAC 2014 Southern California Operation Area | |

|---|---|

| Explosive Ordnance Disposal Platoon Mine Counter Measure Dive Platoons Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Detachment | |

| HMCS Nanaimo (Whitehorse was withdrawn by the Canadian Forces for misconduct)[28] Diving Element | |

| Counter Mine Unit | |

| Mine Counter Measure Dive Platoon | |

| Diving Team | |

| Mine Counter Measure Dive Platoon Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Detachment | |

| Diving Detachment | |

| Maritime Ordnance Disposal Unit | |

| USS Anchorage USS Champion USS Coronado USNS Montford Point USS Scout Mobile Dive Salvage Units Explosive Ordnance Disposal Units Mine Counter Measure Dive Units Marine Mammal Systems | |

RIMPAC 2014 was the 24th exercise in the series and took place from 26 June to 1 August, with an opening reception on 26 June and closing reception 1 August.[1]

For the first time, the Royal Norwegian Navy actively participated in the exercise. Norway sent one Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate and possibly Norwegian marine special forces.[29] China was also invited to send ships from their People's Liberation Army Navy; marking not only the first time China participated in a RIMPAC exercise, but also the first time China participated in a large-scale United States-led naval drill.[30] On 9 June 2014, China confirmed it would be sending four ships to the exercise, a destroyer, frigate, supply ship, and hospital ship.[31][32]

The year's RIMPAC participants were Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Tonga, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[33] Thailand was uninvited from the exercise following a 22 May military coup. Thailand's absence means that 22 nations participated in RIMPAC instead of the 23 that had been advertised.[34] The exercise involved 55 vessels, more than 200 aircraft, and some 25,000 personnel.[23][35]

RIMPAC 2016

| RIMPAC 2016 Southern California Operation Area | |

|---|---|

| HMCS Saskatoon HMCS Yellowknife | |

| ARM Usumacinta | |

| USS Champion USS Freedom USS Pearl Harbor | |

India participated in RIMPAC 2016.[37]

In April 2016, the People's Republic of China was also invited to RIMPAC 2016 despite the tension in South China Sea.[38]

RIMPAC 2018

On 23 May 2018, the Pentagon announced that it had "disinvited" China because of recent militarization of islands in the South China Sea, after China had announced in January that it had been invited.[39] The PRC has previously attended RIMPAC 2014 & 2016.

On 30 May 2018, the US Navy announced that the following navies would take part in the exercise:

In this edition of RIMPAC, the Chilean Navy was responsible for leading the naval exercise, being the first non-English-speaking Navy to carry out this task. The election of Chile as leader of the Task Groups is a recognition of the high performance achieved in recent editions and the quality of its personnel, which since its first participation in 1996 has been demonstrating its preparation and professionalism. This appointment also places this country in a leadership position in the Latin American and world level in the planning and execution of combined naval operations.[40]

Israel, Vietnam and Sri Lanka made their debut in RIMPAC. Brazil was due to make its debut too, but cancelled its participation for the second time.[41] The exercise also included a live firing of the LRASM anti-ship missile for the first time.

RIMPAC 2020

On April 29 2020, the US Navy announced RIMPAC would be held from August 17-30, but due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, it would be at sea only.[42] 25 nations have been invited to participate.[43]

Israel was among the original 25 invited nations, but due to COVID-19, declined to attend.[44]

There has been some opposition to New Zealand's participation and there have been calls from the public for New Zealand not to attend.[45]

Participating units (updated as more information is announced)[46]

Experiments

RIMPAC experiments have included a range of sectors important to international militaries. In RIMPAC 2000, for example, the first of the Strong Angel international humanitarian response demonstrations was held on the Big Island of Hawai'i near Pu'u Pa'a. That series continued with events in the summer of 2004 and again in 2006.

Participants have also conducted exercises in ship-sinking and torpedo usage. They also have tested new naval vessels and technology. For example, in 2004, the United States Navy tested the Australian built HSV-2 Swift, a 321-foot (98 m) experimental wave-piercing catamaran that draws only 11 feet (3.4 m) of water, has a top speed of almost 50 knots (93 km/h; 58 mph), and can transport 605 tons of cargo.

Marines from Kaneohe Bay conducting an amphibious landing in RIMPAC 2004.

Marines from Kaneohe Bay conducting an amphibious landing in RIMPAC 2004. USS Key West at periscope depth, RIMPAC 2004

USS Key West at periscope depth, RIMPAC 2004 Ultra Heavy-Lift Amphibious Connector lands on the shore after disembarking USS Rushmore with heavy equipment during a Marine Corps Advanced Warfighting Experiment during RIMPAC 2014. The prototype is a ship-to-shore connector and is 50% scale.

Ultra Heavy-Lift Amphibious Connector lands on the shore after disembarking USS Rushmore with heavy equipment during a Marine Corps Advanced Warfighting Experiment during RIMPAC 2014. The prototype is a ship-to-shore connector and is 50% scale. Legged Squad Support System (LS3) walks around the Kahuku Training Area during RIMPAC 2014. The LS3 is experimental technology being tested by the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab.

Legged Squad Support System (LS3) walks around the Kahuku Training Area during RIMPAC 2014. The LS3 is experimental technology being tested by the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab._RIMPAC_2014.jpg) Marines follow a Ground Unmanned Support Surrogate (GUSS), experimental technology being tested by the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab during RIMPAC 2014 at Kahuku Training Area.

Marines follow a Ground Unmanned Support Surrogate (GUSS), experimental technology being tested by the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab during RIMPAC 2014 at Kahuku Training Area. Forty-two ships & submarines from 15 nations steam in close formation during RIMPAC 2014

Forty-two ships & submarines from 15 nations steam in close formation during RIMPAC 2014 USS Ronald Reagan steams in close formation as one of forty-two ships & submarines representing 15 nations during RIMPAC 2014. In the background is JDS Ise

USS Ronald Reagan steams in close formation as one of forty-two ships & submarines representing 15 nations during RIMPAC 2014. In the background is JDS Ise

In popular culture

- RIMPAC 2012 was the main setting of the 2012 film Battleship.[47]

- The IMAX documentary film Aircraft Carrier: Guardians of the Sea covers RIMPAC 2014.

References

- "RIMPAC 2014". Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "Russian Warships Arrive at U.S. Pearl Harbor for Joint Drills." RIA Novosti. 1 July 2012.

- "Ships of RIMPAC 2004". Archived from the original on 8 March 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- "Submarines of RIMPAC 2004". Archived from the original on 1 April 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- "Aircraft of RIMPAC 2004". Archived from the original on 6 March 2005. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Barber, Barrie. "RIMPAC 2004 Packs A Punch in Joint Exercise Near Hawaii". Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- "Admiral Patrick M. Walsh (ret.) – iSIGHT Partners". Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- "613th AOC 'connects' RIMPAC 2008". Pacific Air Forces. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class (SW) Mark Logico, USN. "RIMPAC 2010 Officially Opens". NNS100629-22. Commander Navy Region Hawaii Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Robert Stirrup, USN (2 August 2010). "RIMPAC 2010 Officially Concludes as Ships Return to Pearl Harbor". NNS100802-16. Commander, Navy Region Hawaii Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Stephen Votaw, USN (8 August 2008). "USS Ronald Reagan Returns from RIMPAC 2010". NNS100808-01. USS Ronald Reagan Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Aaron Stevens, USN (30 June 2010). "USS Ronald Reagan Arrives in Hawaii for RIMPAC 2010". NNS100630-09. USS Ronald Reagan Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Robert Stirrup, USN (9 July 2010). "Ships Depart Pearl Harbor for RIMPAC 2010 Exercises". NNS100708-18. Commander, Navy Region Hawaii Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Stephen Votaw, USN (24 July 2010). "USS Ronald Reagan Hosts International Navies for Sea Combat Control Exercises During RIMPAC 2010". NNS100724-06. USS Ronald Reagan Public Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "RIMPAC 2012: participating vessels by country". Naval Technology. 17 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "RIMPAC 2012". US Navy. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "RIMPAC 2012: Great Green Fleet, communications and Yellow Sea security". Naval Technology. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "USNS Henry J. Kaiser delivers biofuel for RIMPAC's Great Green Fleet demo".

- "RIMPAC Units Continue To Arrive in Hawaii". US Navy. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "RIMPAC exercise to begin June 29". US Navy. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "RP participates in RIMPAC 2012". Chinese state media. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- "VX-1 Flies P-8 Poseidon during RIMPAC 2012". NNS120729-04. RIMPAC Public Affairs. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "RIMPAC 2014 Participating Forces". Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Air of excitement as Success departs for RIMPAC". Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Pugliese, David (2 July 2014). "HMCS Victoria arrives in Pearl Harbor to take part in RIMPAC 2014". Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- LaGrone, Sam (18 July 2014). "China Sends Uninvited Spy Ship to RIMPAC". U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "ROKS Lee Sun Sin departs, RIMPAC 2014 [Image 17 of 17]". Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Pugliese, David (15 July 2014). "Navy ship ordered back to Canada from California due to personal misconduct from sailors". National Post. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Nå skal Forsvaret øve på Hawaii". vg.no. Verdens Gang. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Editorial, Reuters (22 March 2013). "China to attend major U.S.-hosted naval exercises, but role limited". Reuters.

- "China confirms attendance at U.S.-hosted naval exercises in June". Reuters. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- Tiezzi, Shannon (11 June 2014). "A 'Historic Moment': China's Ships Head to RIMPAC 2014". TheDiplomat.com. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "23 Nations to Participate in Maritime Exercise". 8 May 2014.

- Cole, William (25 June 2014). "Military coup gets Thailand booted from RIMPAC lineup". StarAdvertiser.com. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- Brunnstrom, David; Alexander, David (26 June 2014). "China looks to gain by joining big U.S.-led Pacific naval drills". Reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- "India to participate in world's largest maritime warfare exercise in US next year". 11 December 2015.

- "SECDEF Carter: China Still Invited to RIMPAC 2016 Despite South China Sea Tension - USNI News". 18 April 2016.

- "U.S. kicks China out of military exercise". Politico. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "RIMPAC, el ejercicio naval y marítimo más grande del mundo" (in Spanish). Chile: Revista Vigía de la Armada de Chile. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Brazil drops out of RIMPAC, again". Naval Today. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- https://www.cpf.navy.mil/news.aspx/130607?fbclid=IwAR0Bb8MJHcOyGmSLcsccD-y_5OeeLfWID_hwWgHgK3MFZPPTnrQluiyzspA

- https://www.staradvertiser.com/2020/05/09/hawaii-news/25-nations-invited-to-participate-in-modified-rimpac/

- https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/israel-will-not-participate-in-rimpac-2020-627056

- https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/418720/rimpac-war-games-exercise-new-zealand-government-urged-to-withdraw?fbclid=IwAR244sgrDqbPLjhpZLfgu-m57ag_HBS_1kLiacxvuDi-enJxRk6r9b8Jvlg

- https://www.contactairlandandsea.com/2020/07/05/aussie-ships-deploying-to-se-asia-and-rimpac/?fbclid=IwAR0Rw2susxrTP35IHEpExmz4GyGEu7t3AlqqGPhJXjfGiwLIxHXAl7f58gU

- "Battleship (2012)". IMDb. 18 May 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to RIMPAC. |