Maccabiah Games

The Maccabiah Games (a.k.a. the World Maccabiah Games; Hebrew: משחקי המכביה, or משחקי המכביה העולמית; often referred to as the "Jewish Olympics"), first held in 1932, are an international Jewish and Israeli multi-sport event now held quadrennially in Israel.[1][2][3] It is the third-largest sporting event in the world, with 10,000 athletes competing.[4][5][6] The Maccabiah Games were declared a "Regional Sports Event" by, and under the auspices and supervision of, the International Olympic Committee in 1961.[7][8][9]

| Maccabiah Games |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

|

| Most recent games |

|

All Games

|

| Stadiums |

|

|

|

The 2017 Maccabiah Games, also known as the 20th Maccabiah Games, were held in July 2017.[10] They brought together 10,000 athletes, making it the third-largest international sporting event in the world by number of competitors (after the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup).[5][11][12][13][14] The athletes competed on behalf of 85 countries, in 45 sports.[5]

Originally, the Maccabiah was held every three years. Since the 4th Maccabiah, the event has been held every four years, in the year following the Olympic Games. Competitions at the Maccabiah are organized into four divisions – Open, Juniors, Masters, and Disabled.[2][15] The Games are organized by the Maccabi World Union.

The Maccabiah Games are open to Jewish athletes from around the world, as well as to all Israeli athletes regardless of ethnicity or religion. Arab Israelis have also competed in it.[3][16]

Etymology

The name Maccabiah was chosen after Judah Maccabee, a Jewish leader who defended his country from King Antiochus.[17] Modi'in, Judah's birthplace, is also the starting location of the torch that's used to light the flames at the opening ceremony, a tradition that started at the 4th Maccabiah.[8]

History

The Maccabiah Games were the result of a proposal put forward by Yosef Yekutieli in 1929 at the Maccabi World Congress. Yekutieli, who heard about the Stockholm Olympics, wanted to form a representation for Eretz Yisrael. Following the appointment of the new British Palestine High Commissioner, Sir Arthur Grenfell Wauchope, the Maccabiah got the go-ahead.

The 1st Maccabiah opened on March 28, 1932.[18] The Maccabiah Stadium in Tel Aviv, which was built with donations, was filled to capacity. Roughly 400 athletes from 18 countries took part in everything from swimming, football, and handball, to various athletics. In the first Games, the Polish delegation took first place.[18]

Following the success of the first Games, the 2nd Maccabiah was held from April 2 to 10, 1935, despite official opposition by the British Mandatory government. Over 1,300 athletes from 28 nations participated. The 3rd Maccabiah, which was originally scheduled for spring of 1938,[8] was postponed until 1950 due to British concerns of large-scale illegal immigration,[8] World War II, and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[19] It became the first Maccabiah to be held after the establishment of the State of Israel.

Starting from the 4th Maccabiah, the games were changed to take place every four years in the year following the Olympics. The 15th edition was marred by what became known as the Maccabiah bridge disaster, when a temporary bridge built for the march of athletes at the opening ceremony collapsed, plunging about 100 members of the Australian delegation into the waters of the Yarkon River. Four athletes were killed, and 63 injured.[20][21] More than 5,000 participants from over 50 countries competed in those Games.[21]

Over the last two decades, the number of participants grew to 9,000 athletes in the 19th Maccabiah, from 78 countries, making it the 3rd-largest sporting event in the world and the largest sporting event in 2013, behind the Pan-Am Games and the Olympics.[14][22] It is a forum for Jewish athletes to meet and convene, and provides the athletes with opportunities to explore Israel and Jewish history.[1]

Winter Maccabiah

Prior to World War II there was an attempt to organize a winter Maccabiah. Due to the relatively warm temperatures in Palestine, the winter Maccabiot were organized in European nations. The 1st Winter Maccabiah was held in Zakopane, Poland, February 2 to 5, 1933.[23][24] The games were met with great opposition; the Gazeta Warszawska newspaper encouraged Polish youth to intervene during the games to prevent the "Jewification of Polish winter sports venues".[23]

A second attempt at the winter games was relatively more successful. The 2nd Winter Maccabiah took place February 18 to 22, 1936, in Banská Bystrica (then Czechoslovakia).[24] In the games, 2,000 athletes from 12 nations participated.[25][26] This was the last time a winter Maccabiah was ever held, and the only two Maccabiot to not take place in the Land of Israel; although Maccabi still runs smaller regional winter games to date.

Ceremonies

The Maccabiah ceremonies are two ceremonial events that take place during the first and last days of the Maccabiah games. The ceremonies are an important part of the Jewish culture in Israel and the Zionist movement. The ceremonies of the Maccabiah trace their roots to the early Olympic Games of the 20th century. As such, they share many similarities.

The Maccabiah opening ceremony, which is organized by the Maccabi World Union, has recently been presented in English, Hebrew, and Spanish.

Opening

The opening ceremonies represent the official commencement of the Maccabiah. Some sports however, such as golf and rugby, might start prior to the opening ceremonies in order to finish on time.

The opening ceremony for the first Games was held at the new Maccabiah Stadium. The Stadium, which is located next to the Yarkon River in Tel Aviv, was finished just the night before. The Stadium also hosted the 2nd Maccabiah in 1935. For the 3rd Maccabiah, the opening ceremony took place in a new stadium in Ramat Gan. The stadium has been hosting the opening ceremonies of the Maccabiah ever since, with the exception of the 16th, 19th, and 20th Maccabiah Games which were held in Teddy Stadium, Jerusalem.

The ceremonies often start with the introduction of the active participants of the Maccabi youth movement. After the parade of nations, the opening ceremony continues on with a presentation of artistic displays of music, singing, dance, and theater representative of the Jewish culture. In recent games, Jewish singers from around the world participated in the opening ceremony. For example, in 2013, Grammy Award-winner Miri Ben-Ari and X Factor USA finalist Carly Rose Sonenclar performed at the opening ceremony.[27]

Parade of Nations

Just like at the Olympics, the Maccabiah starts out with a "Parade of Nations", during which most participating athletes march into the stadium, country by country. The countries enter the stadium in accordance with the Hebrew alphabet. The parade of nations, in contrast to some other games, include junior and disabled athletes who also partake in the competitions. In accordance with the Maccabiah's tradition, the Israeli delegation always enters last.

Closing

The closing ceremony of the Maccabiah Games takes place after all sporting events have concluded. Typically, a member of Maccabi or some other well-known figure makes the closing speech and the Games officially close. The ceremony includes large artistic displays of music, singing, and dance. Various Jewish singers perform during the closing ceremony. In recent years, the closing ceremonies included popular musicians and live music and dancing.

Medal presentation

A medal ceremony is held after each Maccabiah event is concluded. The winner, second, and third-place competitors or teams stand on top of a three-tiered rostrum to be awarded their respective medals. Medals are awarded by an official Maccabi member.

Ceremony hosts

| Year | Hosts (s) |

|---|---|

| 1981 | Azaria Rapoport (Closing) |

| 2005 | Becky Griffin and Rodrigo Gonzales |

| 2009 | Galit Giat and Michael HarPaz |

| 2013 | Miri Nevo and Dana Grotsky |

| 2017 |

|

Sports

_-_The_Winners_of_the_10%2C000_M_Walk.jpg)

_-_Israeli_High_Jumping_Champion_Gideon_Harmat.jpg)

The Maccabiah Games recognize all 28 current Olympic sports, plus a number of other sports such as chess, cricket, and netball. In contrast with the Olympic Games and other major international sporting events, the Maccabiah rules regarding accepting new sports are very lenient. New sports are accepted to the Maccabiah Games provided that competitions will only take place if at least four delegations bring competitors for that sport (three in the case of female sports, as well as the junior divisions).[28] As a result, the Maccabiah has held various unique competitions such as duplicate bridge.

Karate, not yet on the Olympic schedule, made its debut in 1977 at the 10th Maccabiah Games. The requisite number of initial countries signed on and agreed to send delegations. Since 1977, karate has participated uninterrupted. Although at the beginning karate was only contested in the fighting or kumite category, forms or kata was included in 1981. In 1985, women's karate was added. Junior and youth categories made their debut in 2009. The World Karate Federation, a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), oversees and supervises the rules of karate competition at the Maccabiah.

The Maccabiah Games are organized into four divisions: Open, Junior, Masters, and Paralympics.

- Open – The Open games are generally unlimited in age, and are intended for the best athletes from each delegation, bound by the governing international rules in each sport.

- Junior – The Junior Maccabiah games are open to any qualifying athlete aged 15–18.

- Masters – The Masters games are for older competitors; they are divided into a number of different age categories.

- Paralympic – The Paralympic games are generally open to all athletes with a range of physical and intellectual disabilities. Past games included Para-cycling, Paralympic swimming, Para table tennis, Half Marathon, and Wheelchair Basketball.

In recent Maccabiot there has been a renewed interest in introducing new sports to the Maccabiah. In the 15th Maccabiah Games, ice hockey was first introduced. Ice hockey was not included in immediately subsequent games, but returned in the 19th Maccabiah. Squash became an official sport in the 10th Maccabiah Games in 1977. The 19th Maccabiah was also granted provisional approval for dressage and jumping competitions from the FEI.[29]

Champions and medalists

Notable participants

Athletes who have competed in the Maccabiah Games include many Olympic gold medalists, world champions, and world record holders. Among them have been Mark Spitz, Lenny Krayzelburg, Jason Lezak, Marilyn Ramenofsky, and Anthony Ervin (swimming); Mitch Gaylord, Abie Grossfeld, Ágnes Keleti, Valery Belenky, and Kerri Strug (gymnastics); Ernie Grunfeld, Danny Schayes, (coaches); Larry Brown, Nat Holman, and Dolph Schayes (basketball); Carina Benninga (field hockey); Lillian Copeland, Gerry Ashworth, and Gary Gubner (track and field); Angela Buxton, Brad Gilbert, Julie Heldman, Allen Fox, Nicolás Massú, and Dick Savitt (tennis); Dave Blackburn (softball); Angelica Rozeanu (table tennis); Sergey Sharikov, Vadim Gutzeit, and Mariya Mazina (fencing); Isaac Berger and Frank Spellman (weightlifting); and Lindsey Durlacher, Jason Goldman, Fred Oberlander and Henry Wittenberg (wrestling); Max Fried and Dean Kremer (baseball); Madison Gordon-Lavaee (volleyball); Donald Spero and Michael Oren (rowing); Bruce Fleisher (golf); and Adam Bacher, Dennis Gamsy, Neil Rosendorff, Marshall Rosen, Bob Herman (cricket);[30] Boris Gelfand and Judit Polgár (chess); Elizabeth Foody (interpretive dance); Adam Rubin (soccer); Aaron R. Schwid (bowling); Jessica Schulman (soccer); Irwin Cotler (ping pong); Marcelo Lipatin, Jeff Agoos, and Jonathan Bornstein (association football), and Steve March Tormé (fast-pitch softball); Shawn Lipman (rugby), Dov Sternberg and Ilyse Sternberg (Karate); and Ori Sasson (judo).[31][32]

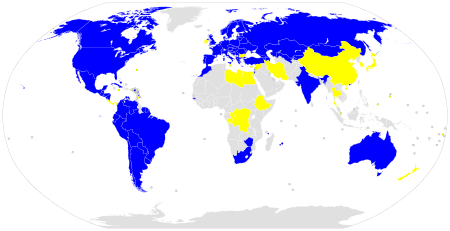

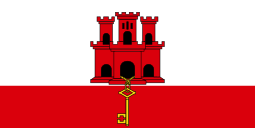

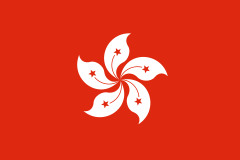

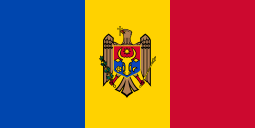

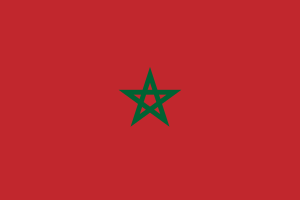

Participating nations

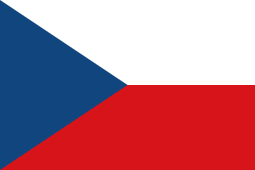

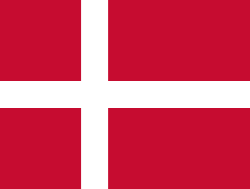

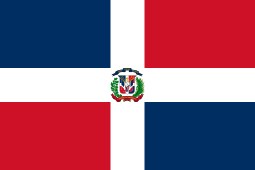

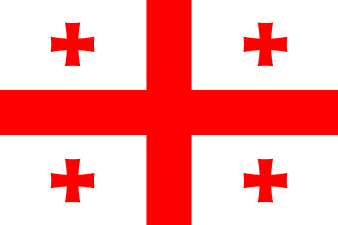

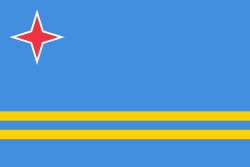

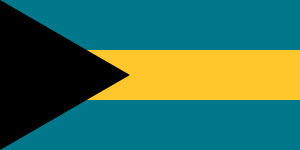

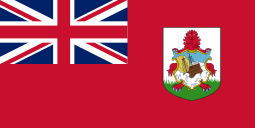

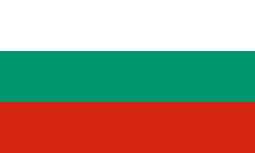

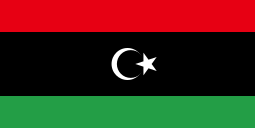

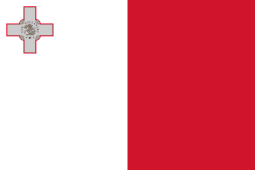

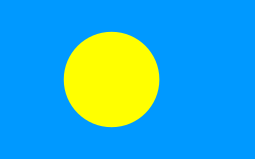

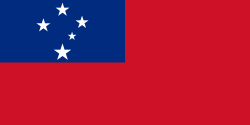

– Past participants.

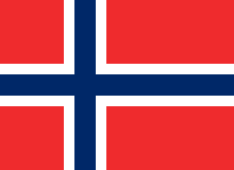

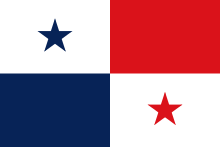

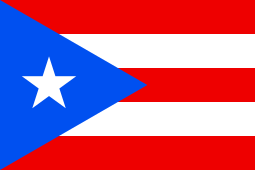

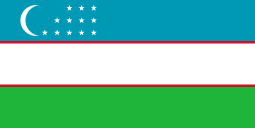

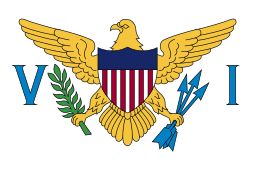

The Maccabiah Games have grown into one of the world's largest sporting events, with 85 participating countries in the current edition of the Maccabiah. Below is a list of countries that participated in the most recent games in 2017. Scroll down for participating nations from the 2014 edition and other games[33]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Early games featured many delegations from the Arab nations. Iran, a Muslim, but not Arab country, which debuted at the 7th Maccabiah, stopped participating following the Iranian Revolution. Some of these countries have participated under multiple flags. Countries that previously participated but did not in the most recent Maccabiah are:

.svg.png)

See also

References

- "About Us – Maccabiah". Maccabiah. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- Nauright, p. 364.

- Goldman, Ilan (July 8, 2013). "Arab athletes at the Maccabiah: Going for gold, seeking recognition". Haaretz. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- "Amar’e Stoudemire to Revisit Israel as a Maccabi Coach," Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times.

- "Records Fall Before Maccabiah Games Even Begin; U.S. squad is largest ever in what officials say is ‘a life-changing experience’," Archived July 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Jewish Week.

- "Maccabiah Games Welcome 9,000 Athletes – Christian News 24–7 – CBN.com". cbn.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Helen Jefferson Lenskyj (2012). Gender Politics and the Olympic Industry. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bard and Schwartz, p. 84.

- "History of the Maccabiah Games". Maccabi Australia. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- "LEE APPOINTED MACCABI GB HEAD OF FOOTBALL FOR 2015 EUROPEAN MACCABI GAMES". Maccabi GB. October 3, 2013. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- "Levine inducted into Jewish sports hall as Maccabiah athletes feted at JC," Archived July 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Ottawa Sun.

- "80 N.J. athletes head to Maccabiah Games in Israel, world's third-largest sporting event". NJ.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015.

- Aharoni, Oren (July 16, 2013). "Biggest Maccabiah ever begins Thursday". Ynet News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- Silverman, Anav (July 22, 2013). "Maccabiah Games: Uniting Jewish Athletes Across the World". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- "Leah Levey Set to Compete at Maccabiah Games in Israel Next Month". Case Western Reserve University. June 21, 2013. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- Porat, Avinoam (June 11, 2005). "Arab Israeli wins Maccabiah gold". Ynet. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- "Spirit of Judah Maccabee strides into the present day". CNN. December 24, 1997. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- Mendelsohn p. 31.

- Nauright, p. 365.

- Nauright, p. 366.

- Bard and Schwartz, p. 85.

- Sinai, Allon (July 18, 2013). "The opening ceremony of 19th Maccabiah Games 2013". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- Mendelsohn p. 26.

- Hanak. p. 1.

- Hanak. p. 2.

- Unknown (February 21, 1936). "Austria Wins Skiing Event in Winter Maccabiah". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- "Watch the Maccabiah Opening Ceremonies". July 18, 2013. The Jewish Exponent. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- 17th Maccabiah Basic Regulations Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "FEI Grants Approval for Horse Sports at Maccabiah Games". Dressage News. March 2, 2013. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- Prittie, Terence (1975). "Israeli cricket". Wisden. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Lieberman, Randall P. "Water polo among sports to be contested at Maccabiah Games". sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Maccabiah". Maccabi World Union. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Games / Competitions". The Maccabiah. July 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

Works cited

- Mendelsohn, Ezra (March 31, 2009). Jews and the Sporting Life : Studies in Contemporary Jewry XXIII. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195382914.

- Simri, Uriel (July 1981). Physical education and sport in the Jewish history and culture : proceedings of an international seminar. Netanya, Israel: Conference publication. LCCN 83112598. OCLC 25200212. OL 3206919M.

- Hanak, Arthur. The Maccabi—Maccabiah Winter Games in 1933 and 1936.

- Nauright, John. John Nauright, Charles Parrish (ed.). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843002. OCLC 814221941.

- Mitchell Geoffrey Bard; Moshe Schwartz (2005). One Thousand and One Facts Everyone Should Know about Israel. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 84. ISBN 9780742543584. LCCN 2005-012466. OCLC 60188587.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maccabiah Games. |

- Official website

- TV report on the Maccabiah Games in Vienna (German)

- European Maccabi Games 2015 Official Website

- Summaries of each of the games at Jewish Sports

- Jewish swimmer to skip world championship for Maccabiah

- The Maccabiyah Games – a sportive best regards from the fifties, Exhibition in the IDF&defense establishment archives