Irish literature

Irish literature comprises writings in the Irish, Latin, and English (including Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from the seventh century and was produced by monks writing in both Latin and Early Irish. In addition to scriptural writing, the monks of Ireland recorded both poetry and mythological tales. There is a large surviving body of Irish mythological writing, including tales such as The Táin and Mad King Sweeny.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Ireland |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

|

Cuisine

|

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts

|

|

Media

|

|

Monuments |

|

Symbols

|

|

The English language was introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland. The Irish language, however, remained the dominant language of Irish literature down to the nineteenth century, despite a slow decline which began in the seventeenth century with the expansion of English power. The latter part of the nineteenth century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English in the greater part of the country, largely due to the Great Famine (Ireland) and the subsequent decimation of the Irish population by starvation and emigration.[1] At the end of the century, however, cultural nationalism displayed a new energy, marked by the Gaelic Revival (which encouraged a modern literature in Irish) and more generally by the Irish Literary Revival.

The Anglo-Irish literary tradition found its first great exponents in Richard Head and Jonathan Swift followed by Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Also written during the eighteenth century, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill's Irish language keen, "Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire", is widely regarded as the greatest poem written in the century in Ireland or Britain, lamenting the death of her husband, the titular Art Uí Laoghaire.

At the end of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, Irish literature saw an unprecedented sequence of globally successful works, especially those by Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, Elizabeth Bowen, C. S. Lewis, Kate O'Brien and George Bernard Shaw, most of whom left Ireland to make a life in other European countries such as England, Spain, France and Switzerland. Meantime, the descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster formed the Ulster-Scots writing tradition, having an especially strong tradition of rhyming poetry.

Though English was the dominant Irish literary language in the twentieth century, much work of high quality appeared in Irish. A pioneering modernist writer in Irish was Pádraic Ó Conaire, and traditional life was given vigorous expression in a series of autobiographies by native Irish speakers from the west coast, exemplified by the work of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig Sayers. Máiréad Ní Ghráda wrote numerous successful plays often influenced by Bertolt Brecht, as well as the first translation of Peter Pan, Tír na Deo, and Manannán, the first Irish language Science fiction book. The outstanding modernist prose writer in Irish was Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and prominent poets included Caitlín Maude, Máirtín Ó Direáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Prominent bilingual writers included Brendan Behan (who wrote poetry and a play in Irish) and Flann O'Brien. Two novels by O'Brien, At Swim Two Birds and The Third Policeman, are considered early examples of postmodern fiction, but he also wrote a satirical novel in Irish called An Béal Bocht (translated as The Poor Mouth). Liam O'Flaherty, who gained fame as a writer in English, also published a book of short stories in Irish (Dúil). Irish-language literature continues to flourish in the modern day with Éilís Ní Dhuibhne and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill being prolific in poetry and prose.

Most attention has been given to Irish writers who wrote in English and who were at the forefront of the modernist movement, notably James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses is considered one of the most influential works of the century. The playwright Samuel Beckett, in addition to a large amount of prose fiction, wrote a number of important plays, including Waiting for Godot. Several Irish writers have excelled at short story writing, in particular Edna O'Brien, Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. Other notable Irish writers from the twentieth century include, poets Eavan Boland and Patrick Kavanagh, dramatists Tom Murphy and Brian Friel and novelists Edna O'Brien and John McGahern. In the late twentieth century Irish poets, especially those from Northern Ireland, came to prominence including Derek Mahon, Medbh McGuckian, John Montague, Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon Influential works of writing continue to emerge in Northern Ireland with huge success such as Anna Burns, Sinéad Morrissey, and Lisa McGee.

Well-known Irish writers in English in the twenty-first century include Edna O'Brien, Colum McCann, Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle, Moya Cannon, John Boyne, Sebastian Barry, Colm Toibín and John Banville, all of whom have all won major awards. Younger writers include Sinéad Gleeson, Paul Murray, Anna Burns, Billy O'Callaghan, Kevin Barry, Emma Donoghue, Donal Ryan and dramatists Marina Carr and Martin McDonagh. Writing in Irish has also continued to flourish.

The Middle Ages: 500–1500

Irish has one of the oldest vernacular literatures in western Europe (after Greek and Latin).[2][3]

The Irish became fully literate with the arrival of Christianity in the fifth century. Before that time a simple writing system known as "ogham" was used for inscriptions. These inscriptions are mostly simple "x son of y" statements. The introduction of Latin led to the adaptation of the Latin alphabet to the Irish language and the rise of a small literate class, both clerical and lay.[4][5]

The earliest works of literature produced in Ireland are by Saint Patrick; his Confessio and Epistola, both in Latin.[6] The earliest literature in Irish consisted of original lyric poetry and prose sagas set in the distant past. The earliest poetry, composed in the 6th century, illustrates a vivid religious faith or describes the world of nature, and was sometimes written in the margins of illuminated manuscripts. "The Blackbird of Belfast Lough", a fragment of syllabic verse probably dating from the 9th century, has inspired reinterpretations and translations in modern times by John Montague, John Hewitt, Seamus Heaney, Ciaran Carson, and Thomas Kinsella, as well as a version into modern Irish by Tomás Ó Floinn.[7]

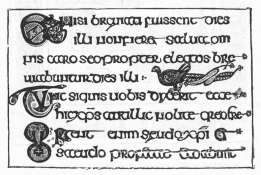

The Book of Armagh is a 9th-century illuminated manuscript written mainly in Latin, containing early texts relating to St Patrick and some of the oldest surviving specimens of Old Irish. It is one of the earliest manuscripts produced by an insular church to contain a near complete copy of the New Testament. The manuscript was the work of a scribe named Ferdomnach of Armagh (died 845 or 846). Ferdomnach wrote the first part of the book in 807 or 808, for Patrick's heir (comarba) Torbach. It was one of the symbols of the office for the Archbishop of Armagh.

The Annals of Ulster (Irish: Annála Uladh) cover years from AD 431 to AD 1540 and were compiled in the territory of what is now Northern Ireland: entries up to AD 1489 were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, under his patron Cathal Óg Mac Maghnusa on the island of Belle Isle on Lough Erne. The Ulster Cycle written in the 12th century, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the traditional heroes of the Ulaid in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Down and Louth. The stories are written in Old and Middle Irish, mostly in prose, interspersed with occasional verse passages. The language of the earliest stories is dateable to the 8th century, and events and characters are referred to in poems dating to the 7th.[8]

After the Old Irish period, there is a vast range of poetry from mediaeval and Renaissance times. By degrees the Irish created a classical tradition in their own language. Verse remained the main vehicle of literary expression, and by the 12th century questions of form and style had been essentially settled, with little change until the 17th century.[9]

Medieval Irish writers also created an extensive literature in Latin: this Hiberno-Latin literature was notable for its learned vocabulary, including a greater use of loanwords from Greek and Hebrew than was common in medieval Latin elsewhere in Europe.

The literary Irish language (known in English as Classical Irish), was a sophisticated medium with elaborate verse forms, and was taught in bardic schools (i.e. academies of higher learning) both in Ireland and Scotland.[10] These produced historians, lawyers and a professional literary class which depended on the aristocracy for patronage. Much of the writing produced in this period was conventional in character, in praise of patrons and their families, but the best of it was of exceptionally high quality and included poetry of a personal nature. Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh (14th century), Tadhg Óg Ó hUiginn (15th century) and Eochaidh Ó hEoghusa (16th century) were among the most distinguished of these poets. Every noble family possessed a body of manuscripts containing genealogical and other material, and the work of the best poets was used for teaching purposes in the bardic schools.[11] In this hierarchical society, fully trained poets belonged to the highest stratum; they were court officials but were thought to still possess ancient magical powers.[12]

Women were largely excluded from the official literature, though female aristocrats could be patrons in their own right. An example is the 15th century noblewoman Mairgréag Ní Cearbhaill, praised by the learned for her hospitality.[13] At that level a certain number of women were literate, and some were contributors to an unofficial corpus of courtly love poetry known as dánta grádha.[14]

Prose continued to be cultivated in the medieval period in the form of tales. The Norman invasion of the 12th century introduced a new body of stories which influenced the Irish tradition, and in time translations were made from English.[15]

Irish poets also composed the Dindsenchas ("lore of places"),[16][17] a class of onomastic texts recounting the origins of place-names and traditions concerning events and characters associated with the places in question. Since many of the legends related concern the acts of mythic and legendary figures, the dindsenchas is an important source for the study of Irish mythology.

Irish mythological and legendary saga cycles

Early Irish literature is usually arranged in four epic cycles. These cycles are considered to contain a series of recurring characters and locations.[18] The first of these is the Mythological Cycle, which concerns the Irish pagan pantheon, the Tuatha Dé Danann. Recurring characters in these stories are Lug, The Dagda and Óengus, while many of the tales are set around the Brú na Bóinne. The principle tale of the Mythological cycle is Cath Maige Tuired (The Battle of Moytura), which shows how the Tuatha Dé Danann defeated the Fomorians. Later synthetic histories of Ireland placed this battle as occurring at the same time as the Trojan War.

Second is the Ulster Cycle, mentioned above, also known as the Red Branch Cycle or the Heroic Cycle. This cycle contains tales of the conflicts between Ulster and Connacht during the legendary reigns of King Conchobar mac Nessa in Ulster and Medb and Ailill in Connacht. The chief saga of the Ulster cycle is Táin Bó Cúailnge, the so-called "Iliad of the Gael,".[19] Other recurring characters include Cú Chulainn, a figure comparable to the Greek hero Achilles, known for his terrifying battle frenzy, or ríastrad.[20], Fergus and Conall Cernach. Emain Macha and Cruachan are the chief locations. The cycle is set around the end of the 1st century BC and the beginning of the 1st century AD, with the death of Conchobar being set at the same day as the Crucifixion.[21]

Third is a body of romance woven round Fionn Mac Cumhaill, his son Oisin, and his grandson Oscar, in the reigns of the High King of Ireland Cormac mac Airt, in the second and third centuries AD. This cycle of romance is usually called the Fenian cycle because it deals so largely with Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his fianna (militia). The Hill of Allen is often associated with the Fenian cycle. The chief tales of the Fenian cycle are Acallam na Senórach (often translated as Colloquy with the Ancients or Tales of the Elders of Ireland) and Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne). While there are early tales regarding Fionn, the majority of the Fenian cycle appears to have been written later than the other cycles.

Fourth is the Historical Cycle, or Cycle of the Kings. The Historical Cycle ranges from the almost entirely mythological Labraid Loingsech, who allegedly became High King of Ireland around 431 BC, to the entirely historical Brian Boru, who reigned as High King of Ireland in the eleventh century AD. The Historical Cycle includes the late medieval tale Buile Shuibhne (The Frenzy of Sweeney), which has influenced the works of T.S. Eliot and Flann O'Brien, and Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib (The War of the Irish with the Foreigners), which tells of Brian Boru's wars against the Vikings. Unlike the other cycles there is not a consistent set of characters or locations in this cycle, as the stories settings span more than a thousand years; though many stories feature Conn Cétchathach or Niall Noígíallach and the Hill of Tara is a common location.

Unusually among European epic cycles, the Irish sagas were written in prosimetrum, i.e. prose, with verse interpolations expressing heightened emotion. Although usually found in manuscripts of later periods, many of these works are feature language that is older than the time of the manuscripts they are contained in. Some of the poetry embedded in the tales is often significantly older the tale it is contained in. It is not unusual to see poetry from the Old Irish period in a tale written in principally in Middle Irish.

While these four cycles are common to readers today they are the invention of modern scholars. There are several tales which do not fit neatly into one category, or not into any category at all. Early Irish writers though of tales in terms of genre's such as Aided (Death-tales), Aislinge (Visions), Cath (Battle-tales), Echtra (Adventures), Immram (Voyages), Táin Bó (Cattle Raids), Tochmarc (Wooings) and Togail (Destructions).[22] As well as Irish mythology there were also adaptations into Middle Irish of Classical mythological tales such as Togail Troí (The Destruction of Troy, adapted from Daretis Phrygii de excidio Trojae historia, purportedly by Dares Phrygius)[23], Togail na Tebe (The Destruction of Thebes, from Statius' Thebaid)[24] and Imtheachta Æniasa (from Virgil's Aeneid).[25]

The Early Modern period: 1500–1800

The 17th century saw the tightening of English control over Ireland and the suppression of the traditional aristocracy. This meant that the literary class lost its patrons, since the new nobility were English speakers with little sympathy for the older culture. The elaborate classical metres lost their dominance and were largely replaced by more popular forms.[26] This was an age of social and political tension, as expressed by the poet Dáibhí Ó Bruadair and the anonymous authors of Pairliment Chloinne Tomáis, a prose satire on the aspirations of the lower classes.[27] Prose of another sort was represented by the historical works of Geoffrey Keating (Seathrún Céitinn) and the compilation known as the Annals of the Four Masters.

The consequences of these changes were seen in the 18th century. Poetry was still the dominant literary medium and its practitioners were often poor scholars, educated in the classics at local schools and schoolmasters by trade. Such writers produced polished work in popular metres for a local audience. This was particularly the case in Munster, in the south-west of Ireland, and notable names included Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin and Aogán Ó Rathaille of Sliabh Luachra. A certain number of local patrons were still to be found, even in the early 19th century, and especially among the few surviving families of the Gaelic aristocracy.[28]

Irish was still an urban language, and continued to be so well into the 19th century. In the first half of the 18th century Dublin was the home of an Irish-language literary circle connected to the Ó Neachtain (Naughton) family, a group with wide-ranging Continental connections.[29]

There is little evidence of female literacy for this period, but women were of great importance in the oral tradition. They were the main composers of traditional laments. The most famous of these is Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire, composed in the late 18th century by Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, one of the last of the Gaelic gentry of West Kerry.[30] Compositions of this sort were not committed to writing until collected in the 19th century.

The manuscript tradition

| Reformation era literature |

|---|

Well after the introduction of printing to Ireland, works in Irish continued to be disseminated in manuscript form. The first printed book in Ireland was the Book of Common Prayer.[31]

Access to the printing press was hindered in the 1500s and the 1600s by official caution, although an Irish version of the Bible (known as Bedell's Bible after the Anglican clergyman who commissioned it) was published in the 17th century. A number of popular works in Irish, both devotional and secular, were available in print by the early 19th century, but the manuscript remained the most affordable means of transmission almost until the end of the century.[32]

Manuscripts were collected by literate individuals (schoolmasters, farmers and others) and were copied and recopied. They might include material several centuries old. Access to them was not confined to the literate, since the contents were read aloud at local gatherings. This was still the case in the late 19th century in Irish-speaking districts.[33]

Manuscripts were often taken abroad, particularly to America. In the 19th century many of these were collected by individuals or cultural institutions.[34]

The Anglo-Irish tradition (1): In the 18th century

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), a powerful and versatile satirist, was Ireland's first earliest notable writer in English. Swift held positions of authority in both England and Ireland at different times. Many of Swift's works reflected support for Ireland during times of political turmoil with England, including Proposal for Universal Use of Irish Manufacture (1720), Drapier's Letters (1724), and A Modest Proposal (1729), and earned him the status of an Irish patriot.[35]

Oliver Goldsmith (1730–1774), born in County Longford, moved to London, where he became part of the literary establishment, though his poetry reflects his youth in Ireland. He is best known for his novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), his pastoral poem The Deserted Village (1770), and his plays The Good-Natur'd Man (1768) and She Stoops to Conquer (1771, first performed in 1773). Edmund Burke (1729–1797) was born in Dublin and came to serve in the House of Commons of Great Britain on behalf of the Whig Party, and establish a reputation in his oratory and published works for great philosophical clarity as well as a lucid literary style.

Literature in Ulster Scots (1): In the 18th century

Scots, mainly Gaelic-speaking, had been settling in Ulster since the 15th century, but large numbers of Scots-speaking Lowlanders, some 200,000, arrived during the 17th century following the 1610 Plantation, with the peak reached during the 1690s.[36] In the core areas of Scots settlement, Scots outnumbered English settlers by five or six to one.[37]

In Ulster Scots-speaking areas the work of Scottish poets, such as Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) and Robert Burns (1759–96), was very popular, often in locally printed editions. This was complemented by a poetry revival and nascent prose genre in Ulster, which started around 1720.[38] A tradition of poetry and prose in Ulster Scots began around 1720.[38] The most prominent being the 'rhyming weaver' poetry, publication of which began after 1750, though a broadsheet was published in Strabane in 1735.[39]

These weaver poets looked to Scotland for their cultural and literary models but were not simple imitators. They were inheritors of the same literary tradition and followed the same poetic and orthographic practices; it is not always immediately possible to distinguish between traditional Scots writing from Scotland and Ulster. Among the rhyming weavers were James Campbell (1758–1818), James Orr (1770–1816), Thomas Beggs (1749–1847).

The Modern period: from 1800

In the 19th century English was well on the way to becoming the dominant vernacular. Down until the Great Famine of the 1840s, however, and even later, Irish was still used over large areas of the south-west, the west and the north-west.

A famous long poem from the beginning of the century is Cúirt an Mheán Oíche (The Midnight Court), a vigorous and inventive satire by Brian Merriman from County Clare. The copying of manuscripts continued unabated. One such collection was in the possession of Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin, a teacher and linen draper of County Kilkenny who kept a unique diary in vernacular Irish from 1827 to 1835 covering local and international events, with a wealth of information about daily life.

The Great Famine of the 1840s hastened the retreat of the Irish language. Many of its speakers died of hunger or fever, and many more emigrated. The hedge schools of earlier decades which had helped maintain the native culture were now supplanted by a system of National Schools where English was given primacy. Literacy in Irish was restricted to a very few.

A vigorous English-speaking middle class was now the dominant cultural force. A number of its members were influenced by political or cultural nationalism, and some took an interest in the literature of the Irish language. One such was a young Protestant scholar called Samuel Ferguson who studied the language privately and discovered its poetry, which he began to translate.[40] He was preceded by James Hardiman, who in 1831 had published the first comprehensive attempt to collect popular poetry in Irish.[41] These and other attempts supplied a bridge between the literatures of the two languages.

The Anglo-Irish tradition (2)

Maria Edgeworth (1767–1849) furnished a less ambiguous foundation for an Anglo-Irish literary tradition. Though not of Irish birth, she came to live there when young and closely identified with Ireland. She was a pioneer in the realist novel.

Other Irish novelists to emerge during the 19th century include John Banim, Gerald Griffin, Charles Kickham and William Carleton. Their works tended to reflect the views of the middle class or gentry and they wrote what came to be termed "novels of the big house". Carleton was an exception, and his Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry showed life on the other side of the social divide. Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, was outside both traditions, as was the early work of Lord Dunsany. One of the premier ghost story writers of the nineteenth century was Sheridan Le Fanu, whose works include Uncle Silas and Carmilla.

The novels and stories, mostly humorous, of Edith Somerville and Violet Florence Martin (who wrote together as Martin Ross), are among the most accomplished products of Anglo-Irish literature, though written exclusively from the viewpoint of the "big house". In 1894 they published The Real Charlotte.

George Moore spent much of his early career in Paris and was one of the first writers to use the techniques of the French realist novelists in English.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), born and educated in Ireland, spent the latter half of his life in England. His plays are distinguished for their wit, and he was also a poet.

The growth of Irish cultural nationalism towards the end of the 19th century, culminating in the Gaelic Revival, had a marked influence on Irish writing in English, and contributed to the Irish Literary Revival. This can be clearly seen in the plays of J.M. Synge (1871–1909), who spent some time in the Irish-speaking Aran Islands, and in the early poetry of William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), where Irish mythology is used in a personal and idiosyncratic way.

Literature in Irish

There was a resurgence of interest in the Irish language in the late 19th century with the Gaelic Revival. This had much to do with the founding in 1893 of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge). The League insisted that the identity of Ireland was intimately bound up with the Irish language, which should be modernised and used as a vehicle of contemporary culture. This led to the publication of thousands of books and pamphlets in Irish, providing the foundation of a new literature in the coming decades.[42]

Patrick Pearse (1879–1916), teacher, barrister and revolutionary, was a pioneer of modernist literature in Irish. He was followed by, among others, Pádraic Ó Conaire (1881–1928), an individualist with a strongly European bent. One of the finest writers to emerge in Irish at the time was Seosamh Mac Grianna (1900–1990), writer of a powerful autobiography and accomplished novels, though his creative period was cut short by illness. His brother Séamus Ó Grianna (1889–1969) was more prolific.

This period also saw remarkable autobiographies from the remote Irish-speaking areas of the south-west – those of Tomás Ó Criomhthain (1858–1937), Peig Sayers (1873–1958) and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin (1904–1950).

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906–1970), a language activist, is generally acknowledged as the doyen (and most difficult) of modern writers in Irish, and has been compared to James Joyce. He produced short stories, two novels and some journalism. Máirtín Ó Direáin (1910–1988), Máire Mhac an tSaoi (b. 1922) and Seán Ó Ríordáin (1916–1977) were three of the finest poets of that generation. Eoghan Ó Tuairisc (1919–1982), who wrote both in Irish and English, was noted for his readiness to experiment in both prose and verse. Flann O'Brien (1911–66), from Northern Ireland, published an Irish language novel An Béal Bocht under the name Myles na gCopaleen.

Caitlín Maude (1941–1982) and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill (b. 1952) may be seen as representatives of a new generation of poets, conscious of tradition but modernist in outlook. The best known of that generation was possibly Michael Hartnett (1941–1999), who wrote both in Irish and English, abandoning the latter altogether for a time.

Writing in Irish now encompasses a broad range of subjects and genres, with more attention being directed to younger readers. The traditional Irish-speaking areas (Gaeltacht) are now less important as a source of authors and themes. Urban Irish speakers are in the ascendancy, and it is likely that this will determine the nature of the literature.

Literature in Ulster Scots (2)

In Ulster Scots-speaking areas there was traditionally a considerable demand for the work of Scottish poets, such as Allan Ramsay and Robert Burns, often in locally printed editions. This was complemented with locally written work, the most prominent being the rhyming weaver poetry, of which, some 60 to 70 volumes were published between 1750 and 1850, the peak being in the decades 1810 to 1840.[39] These weaver poets looked to Scotland for their cultural and literary models and were not simple imitators but clearly inheritors of the same literary tradition following the same poetic and orthographic practices. It is not always immediately possible to distinguish traditional Scots writing from Scotland and Ulster.[38]

Among the rhyming weavers were James Campbell (1758–1818), James Orr (1770–1816), Thomas Beggs (1749–1847), David Herbison (1800–1880), Hugh Porter (1780–1839) and Andrew McKenzie (1780–1839). Scots was also used in the narrative by novelists such as W. G. Lyttle (1844–1896) and Archibald McIlroy (1860–1915). By the middle of the 19th century the Kailyard school of prose had become the dominant literary genre, overtaking poetry. This was a tradition shared with Scotland which continued into the early 20th century.[38]

A somewhat diminished tradition of vernacular poetry survived into the 20th century in the work of poets such as Adam Lynn, author of the 1911 collection Random Rhymes frae Cullybackey, John Stevenson (died 1932), writing as "Pat M'Carty"[43] and John Clifford (1900–1983) from East Antrim.[43] A prolific writer and poet, W. F. Marshall (8 May 1888 – January 1959) was known as "The Bard of Tyrone". Marshall composed poems such as Hi Uncle Sam, Me an' me Da (subtitled Livin' in Drumlister), Sarah Ann and Our Son. He was a leading authority on Mid Ulster English (the predominant dialect of Ulster).

The polarising effects of the politics of the use of English and Irish language traditions limited academic and public interest until the studies of John Hewitt from the 1950s onwards. Further impetus was given by more generalised exploration of non-"Irish" and non-"English" cultural identities in the latter decades of the 20th Century.

In the late 20th century the Ulster Scots poetic tradition was revived, albeit often replacing the traditional Modern Scots orthographic practice with a series of contradictory idiolects.[44] James Fenton's poetry, at times lively, contented, wistful, is written in contemporary Ulster Scots,[38] mostly using a blank verse form, but also occasionally the Habbie stanza.[38] He employs an orthography that presents the reader with the difficult combination of eye dialect, dense Scots, and a greater variety of verse forms than employed hitherto.[44] Michael Longley is another poet who has made use of Ulster Scots in his work.

Philip Robinson's (1946– ) writing has been described as verging on "post-modern kailyard".[45] He has produced a trilogy of novels Wake the Tribe o Dan (1998), The Back Streets o the Claw (2000) and The Man frae the Ministry (2005), as well as story books for children Esther, Quaen o tha Ulidian Pechts and Fergus an tha Stane o Destinie, and two volumes of poetry Alang the Shore (2005) and Oul Licht, New Licht (2009).[46]

A team in Belfast has begun translating portions of the Bible into Ulster Scots. The Gospel of Luke was published in 2009.

Irish literature in English (20th century)

The poet W. B. Yeats was initially influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites and made use of Irish "peasant folk traditions and ancient Celtic myth" in his early poetry.[47] Subsequently, he was drawn to the "intellectually more vigorous" poetry of John Donne, along with Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, and became one of the greatest 20th-century modernist poets.[48] Though Yeats was an Anglo-Irish Protestant he was deeply affected by the Easter Rising of 1916 and supported the independence of Ireland.[49] He received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1923 and was a member of the Irish Senate from 1922–28.[50]

A group of early 20th-century Irish poets worth noting are those associated with the Easter Rising of 1916. Three of the Republican leadership, Patrick Pearse (1879–1916), Joseph Mary Plunkett (1879–1916) and Thomas MacDonagh (1878–1916), were noted poets.[51] It was to be Yeats' earlier Celtic mode that was to be most influential. Amongst the most prominent followers of the early Yeats were Padraic Colum (1881–1972),[52] F. R. Higgins (1896–1941),[53] and Austin Clarke (1896–1974).[54]

Irish poetic Modernism took its lead not from Yeats but from Joyce. The 1930s saw the emergence of a generation of writers who engaged in experimental writing as a matter of course. The best known of these is Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969. Beckett's poetry, while not inconsiderable, is not what he is best known for. The most significant of the second generation Modernist Irish poets who first published in the 1920s and 1930s include Brian Coffey (1905–1995), Denis Devlin (1908–1959), Thomas MacGreevy (1893–1967), Blanaid Salkeld (1880–1959), and Mary Devenport O'Neill (1879–1967).[55]

While Yeats and his followers wrote about an essentially aristocratic Gaelic Ireland, the reality was that the actual Ireland of the 1930s and 1940s was a society of small farmers and shopkeepers. Inevitably, a generation of poets who rebelled against the example of Yeats, but who were not Modernist by inclination, emerged from this environment. Patrick Kavanagh (1904–1967), who came from a small farm, wrote about the narrowness and frustrations of rural life.[56] A new generation of poets emerged from the late 1950s onward, which included Anthony Cronin, Pearse Hutchinson, John Jordan, and Thomas Kinsella, most of whom were based in Dublin in the 1960s and 1970s. In Dublin a number of new literary magazines were founded in the 1960s; Poetry Ireland, Arena, The Lace Curtain, and in the 1970s, Cyphers.

Though the novels of Forrest Reid (1875–1947) are not necessarily well known today, he has been labelled 'the first Ulster novelist of European stature', and comparisons have been drawn between his own coming of age novel of Protestant Belfast, Following Darkness (1912), and James Joyce's seminal novel of growing up in Catholic Dublin, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1924). Reid's fiction, which often uses submerged narratives to explore male beauty and love, can be placed within the historical context of the emergence of a more explicit expression of homosexuality in English literature in the 20th century.[57]

James Joyce (1882–1941) is one of the most significant novelists of the first half of the 20th century, and a major pioneer in the use of the "stream of consciousness" technique in his famous novel Ulysses (1922). Ulysses has been described as "a demonstration and summation of the entire Modernist movement".[58] Joyce also wrote Finnegans Wake (1939), Dubliners (1914), and the semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1914–15). Ulysses, often considered to be the greatest novel of the 20th century, is the story of a day in the life of a city, Dublin. Told in a dazzling array of styles, it was a landmark book in the development of literary modernism.[59] If Ulysses is the story of a day, Finnegans Wake is a night epic, partaking in the logic of dreams and written in an invented language which parodies English, Irish and Latin.[60]

Joyce's high modernist style had its influence on coming generations of Irish novelists, most notably Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), Brian O'Nolan (1911–66) (who published as Flann O'Brien and as Myles na gCopaleen), and Aidan Higgins (1927–2015). O'Nolan was bilingual and his fiction clearly shows the mark of the native tradition, particularly in the imaginative quality of his storytelling and the biting edge of his satire in works such as An Béal Bocht. Samuel Beckett, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, is one of the great figures in 20th-century world literature. Perhaps best known for his plays, he also wrote works of fiction, including Watt (1953) and his trilogy Molloy (1951), Malone Dies (1956) and The Unnamable (1960), all three of which were first written, and published, in French.

The big house novel prospered into the 20th century, and Aidan Higgins' (1927–2015) first novel Langrishe, Go Down (1966) is an experimental example of the genre. More conventional exponents include Elizabeth Bowen (1899–73) and Molly Keane (1904–96) (writing as M.J. Farrell).

With the rise of the Irish Free State and the Republic of Ireland, more novelists from the lower social classes began to emerge. Frequently, these authors wrote of the narrow, circumscribed lives of the lower-middle classes and small farmers. Exponents of this style range from Brinsley MacNamara (1890–1963) to John McGahern (1934–2006). Other notable novelists of the late 20th and early 21st century include John Banville, Sebastian Barry, Seamus Deane, Dermot Healy, Jennifer Johnston, Patrick McCabe, Edna O'Brien, Colm Tóibín, and William Trevor.

The Irish short story has proved a popular genre, with well-known practitioners including Frank O'Connor, Seán Ó Faoláin, and William Trevor.

A total of four Irish writers have won the Nobel Prize for Literature – W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney.

Literature of Northern Ireland

After 1922 Ireland was partitioned into the independent Irish Free State, and Northern Ireland, which retained a constitutional connection to the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland has for several centuries consisted of two distinct communities, Protestant, Ulster Scots and Irish Catholics. While the Protestants majority emphasise the constitutional ties to the United Kingdom, most Catholics would prefer a United Ireland. The long-standing cultural and political division led to sectarian violence in the late 1960s known as The Troubles, which officially ended in 1998, though sporadic violence has continued. This cultural division created, long before 1922, two distinct literary cultures.

C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) and Louis MacNeice (1907–63) are two writers who were born and raised in Northern Ireland, but whose careers took them to England. C. S. Lewis was a poet, novelist, academic, medievalist, literary critic, essayist, lay theologian, and Christian apologist. Born in Belfast, he held academic positions at both Oxford University, and Cambridge University. He is best known both for his fictional work, especially The Screwtape Letters (1942), The Chronicles of Narnia (1949–54), and The Space Trilogy (1938–45), and for his non-fiction Christian apologetics, such as Mere Christianity, Miracles, and The Problem of Pain. His faith had a profound effect on his work, and his wartime radio broadcasts on the subject of Christianity brought him wide acclaim.

Louis MacNeice was a poet and playwright. He was part of the generation of "thirties poets" that included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis, nicknamed "MacSpaunday" as a group – a name invented by Roy Campbell, in his Talking Bronco (1946). His body of work was widely appreciated by the public during his lifetime. Never as overtly (or simplistically) political as some of his contemporaries, his work shows a humane opposition to totalitarianism as well as an acute awareness of his Irish roots. MacNeice felt estranged from the Presbyterian Northern Ireland, with its "voodoo of the Orange bands",[61] but felt caught between British and Irish identities.[62]

Northern Ireland has also produced a number of significant poets since 1945, including John Hewitt, John Montague, Seamus Heaney, Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon, James Fenton, Michael Longley, Frank Ormsby, Ciarán Carson and Medbh McGuckian. John Hewitt (1907–87), whom many consider to be the founding father of Northern Irish poetry, was born in Belfast, and began publishing in the 1940s. Hewitt was appointed the first writer-in-residence at Queen's University, Belfast in 1976. His collections include The Day of the Corncrake (1969) and Out of My Time: Poems 1969 to 1974 (1974) and his Collected Poems in 1991.

John Montague (1929– ) was born in New York and brought up in County Tyrone. He has published a number of volumes of poetry, two collections of short stories and two volumes of memoir. Montague published his first collection in 1958 and the second in 1967. In 1998 he became the first occupant of the Ireland Chair of Poetry[63] (virtually Ireland's Poet laureate). Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) is the most famous of the poets who came to prominence in the 1960s and won the Nobel prize in 1995. In the 1960s Heaney, Longley, Muldoon, and others, belonged to the so-called Belfast Group. Heaney in his verse translation of Beowulf (2000) uses words from his Ulster speech.[64] A Catholic from Northern Ireland, Heaney rejected his British identity and lived in the Republic of Ireland for much of his later life.[65]

James Fenton's poetry is written in contemporary Ulster Scots, and Michael Longley (1939– ) has experimented with Ulster Scots for the translation of Classical verse, as in his 1995 collection The Ghost Orchid. Longley has spoken of his identity as a Northern Irish poet: "some of the time I feel British and some of the time I feel Irish. But most of the time I feel neither and the marvellous thing about the Good Friday agreement was that it allowed me to feel more of each if I wanted to."[66] He was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 2001. Medbh McGuckian's, (born Maeve McCaughan, 1950) first published poems appeared in two pamphlets in 1980, the year in which she received an Eric Gregory Award. Medbh McGuckian's first major collection, The Flower Master (1982), was awarded a Rooney prize for Irish Literature, an Ireland Arts Council Award (both 1982) and an Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize (1983). She is also the winner of the 1989 Cheltenham Prize for her collection On Ballycastle Beach, and has translated into English (with Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin) The Water Horse (1999), a selection of poems in Irish by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill. Among her recent collections are The Currach Requires No Harbours (2007), and My Love Has Fared Inland (2008). Paul Muldoon (1951– ) has published over thirty collections and won a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the T. S. Eliot Prize. He held the post of Oxford Professor of Poetry from 1999 to 2004. Derek Mahon's (1941– ) first collection Twelve Poems appeared in 1965. His poetry, which is influenced by Louis MacNeice and W. H. Auden, is "often bleak and uncompromising".[67] Though Mahon was not an active member of The Belfast Group, he associated with the two members, Heaney and Longley, in the 1960s.[68] Ciarán Carson's poem Belfast Confetti, about the aftermath of an IRA bomb, won The Irish Times Irish Literature Prize for Poetry in 1990.[69]

The most significant dramatist from Northern Ireland is Brian Friel (1929– ), from Omagh, County Tyrone,[70][71][72][73] hailed by the English-speaking world as an "Irish Chekhov",[74] and "the universally accented voice of Ireland".[75] Friel is best known for plays such as Philadelphia, Here I Come! and Dancing at Lughnasa but has written more than thirty plays in a six-decade spanning career that has seen him elected Saoi of Aosdána. His plays have been a regular feature on Broadway.[76][77][78][79]

Among the most important novelists from Northern Ireland are Flann O'Brien (1911–66), Brian Moore (1921–1999), and Bernard MacLaverty (1942–). Flann O'Brien, Brian O'Nolan, Irish: Brian Ó Nualláin, was a novelist, playwright and satirist, and is considered a major figure in twentieth century Irish literature. Born in Strabane, County Tyrone, he also is regarded as a key figure in postmodern literature.[80] His English language novels, such as At Swim-Two-Birds, and The Third Policeman, were written under the nom de plume Flann O'Brien. His many satirical columns in The Irish Times and an Irish language novel An Béal Bocht were written under the name Myles na gCopaleen. O'Nolan's novels have attracted a wide following for their bizarre humour and Modernist metafiction. As a novelist, O'Nolan was powerfully influenced by James Joyce. He was nonetheless sceptical of the cult of Joyce, which overshadows much of Irish writing, saying "I declare to God if I hear that name Joyce one more time I will surely froth at the gob." Brian Moore was also a screenwriter[81][82][83] and emigrated to Canada, where he lived from 1948 to 1958, and wrote his first novels.[84] He then moved to the United States. He was acclaimed for the descriptions in his novels of life in Northern Ireland after the Second World War, in particular his explorations of the inter-communal divisions of The Troubles. He was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1975 and the inaugural Sunday Express Book of the Year award in 1987, and he was shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times (in 1976, 1987 and 1990). His novel Judith Hearne (1955) is set in Belfast. Bernard MacLaverty, from Belfast, has written the novels Cal; Lamb (1983), which describes the experiences of a young Irish Catholic involved with the IRA; Grace Notes, which was shortlisted for the 1997 Booker Prize, and The Anatomy School. He has also written five acclaimed collections of short stories, the most recent of which is Matters of Life & Death. He has lived in Scotland since 1975.

Other noteworthy writers from Northern Ireland include poet Robert Greacen (1920–2008), novelist Bob Shaw (1931–96),[85] and science fiction novelist Ian McDonald (1960). Robert Greacen, along with Valentin Iremonger, edited an important anthology, Contemporary Irish Poetry in 1949. Robert Greacen was born in Derry, lived in Belfast in his youth and then in London during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. He won the Irish Times Prize for Poetry in 1995 for his Collected Poems, and subsequently he moved to Dublin when he was elected a member of Aosdana. Shaw was a science fiction author, noted for his originality and wit. He won the Hugo Award for Best Fan Writer in 1979 and 1980. His short story "Light of Other Days" was a Hugo Award nominee in 1967, as was his novel The Ragged Astronauts in 1987.

Theatre

The first well-documented instance of a theatrical production in Ireland is a 1601 staging of Gorboduc presented by Lord Mountjoy Lord Deputy of Ireland in the Great Hall in Dublin Castle. Mountjoy started a fashion, and private performances became quite commonplace in great houses all over Ireland over the following thirty years. The Werburgh Street Theatre in Dublin is generally identified as the "first custom-built theatre in the city," "the only pre-Restoration playhouse outside London," and the "first Irish playhouse." The Werburgh Street Theatre was established by John Ogilby at least by 1637 and perhaps as early as 1634.[86]

The earliest Irish-born dramatists of note were: William Congreve (1670–1729), author of The Way of the World (1700) and one of the most interesting writers of Restoration comedies in London; Oliver Goldsmith (1730–74) author of The Good-Natur'd Man (1768) and She Stoops to Conquer (1773); Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816), known for The Rivals, and The School for Scandal. Goldsmith and Sheridan were two of the most successful playwrights on the London stage in the 18th century.

In the 19th century, Dion Boucicault (1820–90) was famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the Atlantic as one of the most successful actor-playwright-managers then in the English-speaking theatre. The New York Times heralded him in his obituary as "the most conspicuous English dramatist of the 19th century."[87]

It was in the last decade of the century that the Irish theatre came of age with the establishment in Dublin in 1899 of the Irish Literary Theatre, and emergence of the dramatists George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) and Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), though both wrote for the London theatre. Shaw's career began in the last decade of the nineteenth century, and he wrote more than 60 plays. George Bernard Shaw turned the Edwardian theatre into an arena for debate about important political and social issues, like marriage, class, "the morality of armaments and war" and the rights of women.[88]

In 1903 a number of playwrights, actors and staff from several companies went on to form the Irish National Theatre Society, later to become the Abbey Theatre. It performed plays by W.B. Yeats (1865–1939), Lady Gregory (1852–1932), John Millington Synge (1871–1909), and Seán O'Casey (1880–1964). Equally importantly, through the introduction by Yeats, via Ezra Pound, of elements of the Noh theatre of Japan, a tendency to mythologise quotidian situations, and a particularly strong focus on writings in dialects of Hiberno-English, the Abbey was to create a style that held a strong fascination for future Irish dramatists.[89]

Synge's most famous play, The Playboy of the Western World, "caused outrage and riots when it was first performed" in Dublin in 1907.[90] O'Casey was a committed socialist and the first Irish playwright of note to write about the Dublin working classes. O'Casey's first accepted play, The Shadow of a Gunman, which is set during the Irish War of Independence, was performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1923. It was followed by Juno and the Paycock (1924) and The Plough and the Stars (1926). The former deals with the effect of the Irish Civil War on the working class poor of the city, while the latter is set in Dublin in 1916 around the Easter Rising.

The Gate Theatre, founded in 1928 by Micheál MacLiammóir, introduced Irish audiences to many of the classics of the Irish and European stage.

The twentieth century saw a number of Irish playwrights come to prominence. These included Denis Johnston (1901–84), Samuel Beckett (1906–89), Brendan Behan (1923–64), Hugh Leonard (1926–2009), John B. Keane (1928–2002), Brian Friel (1929– ), Thomas Kilroy (1934– ), Tom Murphy (1935– ), and Frank McGuinness (1953– ),

Denis Johnston's most famous plays are The Old Lady Says No! (1929), and The Moon in the Yellow River (1931).

While there no doubt that Samuel Beckett is an Irishman he lived much of his life in France and wrote several works first in French. His most famous plays are Waiting for Godot (1955) (originally En attendant Godot, 1952), Endgame (originally Fin de partie) (1957), Happy Days (1961), written in English, all of which profoundly affected British drama.

In 1954, Behan's first play The Quare Fellow was produced in Dublin. It was well received; however, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop in Stratford, London, that gained Behan a wider reputation – this was helped by a famous drunken interview on BBC television. Behan's play The Hostage (1958), his English-language adaptation of his play in Irish An Giall, met with great success internationally.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Hugh Leonard was the first major Irish writer to establish a reputation in television, writing extensively for television, including original plays, comedies, thrillers and adaptations of classic novels for British television.[91] He was commissioned by RTÉ to write Insurrection, a 50th anniversary dramatic reconstruction of the Irish uprising of Easter 1916. Leonard's Silent Song, adapted for the BBC from a short story by Frank O'Connor, won the Prix Italia in 1967.[92]

Three of Leonard's plays have been presented on Broadway: The Au Pair Man (1973), which starred Charles Durning and Julie Harris; Da (1978); and A Life (1980).[93] Of these, Da, which originated off-off-Broadway at the Hudson Guild Theatre before transferring to the Morosco Theatre, was the most successful, running for 20 months and 697 performances, then touring the United States for ten months.[94] It earned Leonard both a Tony Award and a Drama Desk Award for Best Play.[95] It was made into a film in 1988.

Brian Friel, from Northern Ireland, has been recognised as a major Irish and English-language playwright almost since the first production of "Philadelphia, Here I Come!" in Dublin in 1964.[96]

Tom Murphy is a major contemporary playwright[97] and was honoured by the Abbey Theatre in 2001 by a retrospective season of six of his plays. His plays include the historical epic Famine (1968), which deals with the Irish Potato Famine between 1846 and spring 1847, The Sanctuary Lamp (1975), The Gigli Concert (1983) and Bailegangaire (1985).

Frank McGuinness first came to prominence with his play The Factory Girls, but established his reputation with his play about World War I, Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, which was staged in Dublin's Abbey Theatre in 1985 and internationally. The play made a name for him when it was performed at Hampstead Theatre.[98] It won numerous awards including the London Evening Standard "Award for Most Promising Playwright" for McGuinness.

Since the 1970s, a number of companies have emerged to challenge the Abbey's dominance and introduce different styles and approaches. These include Focus Theatre, The Children's T Company, the Project Theatre Company, Druid Theatre, Rough Magic, TEAM, Charabanc, and Field Day. These companies have nurtured a number of writers, actors, and directors who have since gone on to be successful in London, Broadway and Hollywood.

- Irish language theatre

Conventional drama did not exist in Irish before the 20th century. The Gaelic Revival stimulated the writing of plays, aided by the founding in 1928 of An Taibhdhearc, a theatre dedicated to the Irish language. The Abbey Theatre itself was reconstituted as a bilingual national theatre in the 1940s under Ernest Blythe, but the Irish language element declined in importance.[99]

In 1957, Behan's play in the Irish language An Giall had its debut at Dublin's Damer Theatre. Later an English-language adaptation of An Giall, The Hostage, met with great success internationally.

Drama in Irish has since encountered grave difficulties, despite the existence of interesting playwrights such as Máiréad Ní Ghráda. The Taidhbhearc has declined in importance and it is difficult to maintain professional standards in the absence of a strong and lively audience. The tradition persists, however, thanks to troupes like Aisling Ghéar.[100]

See also

Footnotes

- Falc’Her-Poyroux, Erick (1 May 2015). "'The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption". Halshs Archives-Ouvertes. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Maureen O'Rourke Murphy, James MacKillop. An Irish Literature Reader. Syracuse University Press. p. 3.

- "Languages : Indo-European Family". Krysstal.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Dillon and Chadwick (1973), pp. 241–250

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp. 54–72

- "Saint Patrick's Confessio". Confessio. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Sansom, Ian (20 November 2008). "The Blackbird of Belfast Lough keeps singing". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Garret Olmsted, "The Earliest Narrative Version of the Táin: Seventh-century poetic references to Táin bó Cúailnge", Emania 10, 1992, pp. 5–17

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp. 147–156

- See the foreword in Knott (1981).

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp.150–194

- For a discussion of poets' supernatural powers, inseparable from their social and literary functions, see Ó hÓgáin (1982).

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp.165–6.

- Examples can be found in O'Rahilly (2000).

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), p. 149.

- dind "notable place"; senchas "old tales, ancient history, tradition" – Dictionary of the Irish Language, Compact Edition, 1990, pp. 215, 537

- Collins Pocket Irish Dictionary p. 452

- Poppe, Erich (2008). Of cycles and other critical matters: some issues in medieval Irish literary history. Cambridge: Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic, University of Cambridge.

- MacDonald, Keith Norman (1904). "The Reasons Why I Believe in the Ossianic Poems". The Celtic Monthly: A Magazine for Highlanders. Glasgow: Celtic Press. 12: 235. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Literally "the act of contorting, a distortion" (Dictionary of the Irish Language, Compact Edition, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 1990, p. 507)

- Meyer, Kuno. "The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes". CELT - Corpus of Electronic Texts. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- Mac Cana, Pronsias (1980). The Learned Tales of Medieval Ireland. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 9781855001206.

- "Togail Troí". Van Hamel Codecs. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Togail na Tebe". Van Hamel Codecs. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Imtheachta Æniasa". Van Hamel Codecs. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- TLG 201–223

- See the introduction to Williams (1981). The text is bilingual.

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp. 252–268, 282–290. See Corkery (1925) for a detailed discussion of the social context.

- Caerwyn Williams and Ní Mhuiríosa (1979), pp. 279–282.

- See the introduction to Ó Tuama, Seán (1961) (ed.), Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire, An Clóchomhar Tta, Baile Átha Cliath.

- "Church of Ireland - A Member of the Anglican Communion". Ireland.anglican.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- See Niall Ó Ciosáin in Books beyond the Pale: Aspects of the Provincial Book Trade in Ireland before 1850, Gerard Long (ed.). Dublin: Rare Books Group of the Library Association of Ireland. 1996. ISBN 978-0-946037-31-5

- Ó Madagáin (1980), pp.24–38.

- Mac Aonghusa (1979), p.23.

- Stephen DNB pp. 217–218

- Montgomery & Gregg 1997: 585

- Adams 1977: 57

- The historical presence of Ulster-Scots in Ireland, Robinson, in The Languages of Ireland, ed. Cronin and Ó Cuilleanáin, Dublin 2003 ISBN 1-85182-698-X

- Rhyming Weavers, Hewitt, 1974

- O'Driscoll (1976), pp. 23–32.

- O'Driscoll (1976), pp. 43–44.

- Ó Conluain and Ó Céileachair (1976), pp. 133–135.

- Ferguson (ed.) 2008, Ulster-Scots Writing, Dublin, p. 21 ISBN 978-1-84682-074-8

- Gavin Falconer (2008) review of "Frank Ferguson, Ulster-Scots Writing: an anthology" Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Ulster-Scots Writing, ed. Ferguson, Dublin 2008 ISBN 978-1-84682-074-8

- "Philip Robinson". Ulsterscotslanguage.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne-Davies. (New York: Prentice Hall, 1990), pp. 1036–7.

- The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature (1990), pp. 1036-7.

- The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature (1990), p.1037.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Margaret Drabble. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p.1104.

- Kilmer, Joyce (7 May 1916). "Poets Marched in the Van of Irish Revolt". New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2008. Available online free in the pre-1922 NYT archives.

- "Padraic Colum". Poetry Foundation. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Frederick Robert Higgins Poetry Irish culture and customs - World Cultures European". Irishcultureandcustoms.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Harmon, Maurice. Austin Clarke, 1896–1974: A Critical Introduction. Wolfhound Press, 1989.

- Alex David "The Irish Modernists" in The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary Irish Poetry, ed. Matthew Campbell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp76-93.

- "Patrick Kavanagh". Poetry Foundation. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Guide to Print Collections – Forrest Reid Collection". University of Exeter. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- Beebe, Maurice (Fall 1972). "Ulysses and the Age of Modernism". James Joyce Quarterly (University of Tulsa) 10 (1): p. 176.

- Richard Ellmann, James Joyce. Oxford University Press, revised edition (1983).

- James Mercanton. Les heures de James Joyce, Diffusion PUF., 1967, p.233.

- MacNeice, Louis (1939). Autumn Journal.

- Poetry in the British Isles: Non-Metropolitan Perspectives. University of Wales Press. 1995. ISBN 0708312667.

- "Poet Laureate". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Heaney, Seamus (2000). Beowulf. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393320979.

- Sameer Rahim, "Interview with Seamus Heaney". The Telegraph, 11 April 2009.

- Wroe, Nicholas (21 August 2004). "Middle man". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Margaret Drabble, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p.616.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, (1996), p.616; beck.library.emory.edu/BelfastGroup/web/html/overview.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nightingale, Benedict. "Brian Friel's letters from an internal exile". The Times. 23 February 2009. "But if it fuses warmth, humour and melancholy as seamlessly as it should, it will make a worthy birthday gift for Friel, who has just turned 80, and justify his status as one of Ireland's seven Saoi of the Aosdána, meaning that he can wear the Golden Torc round his neck and is now officially what we fans know him to be: a Wise Man of the People of Art and, maybe, the greatest living English-language dramatist."

- "Londonderry beats Norwich, Sheffield and Birmingham to the bidding punch". Londonderry Sentinel. 21 May 2010.

- Canby, Vincent."Seeing, in Brian Friel's Ballybeg". The New York Times. 8 January 1996. "Brian Friel has been recognized as Ireland's greatest living playwright almost since the first production of "Philadelphia, Here I Come!" in Dublin in 1964. In succeeding years he has dazzled us with plays that speak in a language of unequaled poetic beauty and intensity. Such dramas as "Translations," "Dancing at Lughnasa" and "Wonderful Tennessee," among others, have given him a privileged place in our theater."

- Kemp, Conrad. "In the beginning was the image". Mail & Guardian. 25 June 2010. "Brian Friel, who wrote Translations and Philadelphia ... Here I Come, and who is regarded by many as one of the world's greatest living playwrights, has suggested that there is, in fact, no real need for a director on a production."

- Winer, Linda."Three Flavors of Emotion in Friel's Old Ballybeg". Newsday. 23 July 2009. "FOR THOSE OF US who never quite understood why Brian Friel is called "the Irish Chekhov," here is "Aristocrats" to explain – if not actually justify – the compliment."

- O'Kelly, Emer. "Friel's deep furrow cuts to our heart". Sunday Independent. 6 September 2009.

- Lawson, Carol. "Broadway; Ed Flanders reunited with Jose Quintero for 'Faith Healer.'". The New York Times. 12 January 1979. "ALL the pieces are falling into place for Brian Friel's new play, "Faith Healer," which opens 5 April on Broadway."

- McKay, Mary-Jayne. "Where Literature Is Legend". CBS News. 16 March 2010. "Brian Friel's Dancing at Lughnasa had a long run on Broadway"

- Osborne, Robert. "Carroll does cabaret". Reuters/The Hollywood Reporter. 5 March 2007. "Final curtains fall Sunday on three Broadway shows: Brian Friel's "Translations" at the Biltmore; "The Apple Tree," with Kristin Chenoweth, at Studio 54; David Hare's "The Vertical Hour," with Julienne Moore and Bill Nighy, at the Music Box, the latter directed by Sam Mendes"

- Staunton, Denis. "Three plays carry Irish hopes of Broadway honours". The Irish Times. 10 June 2006.

- "Celebrating Flann O'Brien", Los Angeles Times, 13 October 2011.

- "Brian Moore: Forever influenced by loss of faith". BBC Online. 12 January 1999. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Cronin, John (13 January 1999). "Obituary: Shores of Exile". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Walsh, John (14 January 1999). "Obituary: Brian Moore". The Independent. London. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Lynch, Gerald. "Brian Moore". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Nicholls 1981

- Alan J. Fletcher, Drama, Performance, and Polity in Pre-Cromwellian Ireland, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1999; pp. 261–4.

- "Dion Boucicault", The New York Times, 19 September 1890

- "English literature - History, Authors, Books, & Periods". Britannica.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Sands, Maren. "The Influence of Japanese Noh Theater on Yeats". Colorado State University. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature. (1996), p.781.

- Fintan, O'Toole (13 February 2009). "Hugh Leonard Obituary". Irish Times.

- "Prix Italia Winners" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Irish literature at the Internet Broadway Database

- Da at the Internet Broadway Database

- IBDB Da:Awards

- Nightingale, Benedict. "Brian Friel's letters from an internal exile". The Times. 23 February 2009; "Seeing, in Brian Friel's Ballybeg". The New York Times. 8 January 1996.

- McKeon, Belinda (9 July 2012). "Home to Darkness: An Interview with Playwright Tom Murphy". Paris Review. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Maxwell, Dominic. "Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme at Hampstead Theatre, NW3". The Times. Retrieved on 25 June 2009.

- Hoch, John C. (2006). Celtic Culture: An Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 980–981 ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0

- "Aisling Ghéar, Irish Language Theatre". Aislingghear.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

References

- Brady, Anne & Cleeve, Brian (1985). Biographical Dictionary of Irish Writers. Lilliput. ISBN 978-0-946640-11-9

- Educational Media Solutions (2012) 'Reading Ireland, Contemporary Irish Writers in the Context of Place'. Films Media Group. ISBN 978-0-81609-056-3

- Jeffares, A. Norman (1997). A Pocket History of Irish Literature. O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-0-86278-502-4

- Welsh, Robert (ed.) & Stewart, Bruce (ed.) (1996). The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866158-0

- Wright, Julia M. (2008). Irish Literature, 1750–1900: An Anthology. Blackwell Press. ISBN 978-1-4051-4520-6

- Caerwyn Williams, J.E. agus Ní Mhuiríosa, Máirín (1979). Traidisiún Liteartha na nGael. An Clóchomhar Tta. Baile Átha Cliath. Revival 336–350

- Corkery, Daniel (1925). The Hidden Ireland: A Study of Gaelic Munster in the Eighteenth Century. M.H. Son, Ltd. Dublin.

- Céitinn, Seathrún (1982) (eag. De Barra, Pádraig). Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, Athnua 1 & 2. Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta. Baile Átha Cliath. A two volume version of Keating's history in modernised spelling.

- Crosson, Seán (2008). " 'The Given Note' Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry". Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Dublin. ISBN 978-1847185693 An overview of the historical relationship between poetry and music in Ireland.

- De Bhaldraithe, Tomás (ed.) (1976 – third printing). Cín Lae Amhlaoibh. An Clóchomhar Tta. Baile Átha Cliath. ISBN 978-0-7171-0512-0. A shortened version of the diaries of Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin. There is an English translation, edited by de Bhaldraithe: Diary of an Irish Countryman 1827 – 1835. Mercier Press. ISBN 978-1-85635-042-6

- De Brún, Pádraig and Ó Buachalla, Breandán and Ó Concheanainn, Tomás (1975 – second printing) Nua-Dhuanaire: Cuid 1. Institiúid Ardléinn Bhaile Átha Cliath.

- Dillon, Myles and Chadwick, Nora (1973). The Celtic Realms. Cardinal. London. ISBN 978-0-351-15808-7 pp. 298–333

- Williams, J.A. (ed.) (1981). Pairlement Chloinne Tomáis. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Dublin.

- Knott, Eleanor (1981 – second printing). An Introduction to Irish Syllabic Poetry of the Period 1200–1600. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Dublin.

- Merriman, Brian: Ó hUaithne, Dáithí (ed.) (1974 – fourth printing). Cúirt an Mheán Oíche. Preas Dolmen. Baile Átha Cliath. ISBN 978-0-85105-002-7

- Mac Aonghusa, Proinsias (1979). ‘An Ghaeilge i Meiriceá’ in Go Meiriceá Siar, Stiofán Ó hAnnracháin (ed.). An Clóchomhar Tta.

- Mac hÉil, Seán (1981). Íliad Hóiméar. Ficina Typofographica. Gaillimh. ISBN 978-0-907775-01-0

- Nicholls, Kenneth (1972). Gaelic and Gaelicised Ireland in the Middle Ages. Gill and MacMillan. Dublin. ISBN 978-0-7171-0561-8

- Ó Conluain, Proinsias and Ó Céileachair, Donncha (1976 – second printing). An Duinníneach. Sáirséal agus Dill. ISBN 978-0-901374-22-6

- O’Driscoll, Robert (1976). An Ascendancy of the Heart: Ferguson and the Beginnings of Modern Irish Literature in English. The Dolmen Press. Dublin. ISBN 978-0-85105-317-2

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1982). An File. Oifig an tSoláthair. Baile Átha Cliath.

- Ó Madagáin, Breandán (1980 – second edition). An Ghaeilge i Luimneach 1700–1900. An Clóchomhar Tta. Baile Átha Cliath. ISBN 978-0-7171-0685-1

- O’Rahilly, Thomas F. (Ed.) (2000 – reprint). Dánta Grádha: An Anthology of Irish Love Poetry (1350–1750). Cork University Press. ISBN 978-0-902561-09-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Literature of Ireland. |

- National Library of Ireland: Premier cultural institution holding Irish literary collections

- CELT: The online resource for Irish history, literature and politics

- The Irish Playography database