National Eisteddfod of Wales

The National Eisteddfod of Wales (Welsh: Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru) is the most important of several eisteddfodau that are held annually, mostly in Wales. Its eight days of competitions and performances are considered the largest music and poetry festival in Europe.[1] Competitors typically number 6,000 or more, and overall attendance generally exceeds 150,000 visitors.[2] The 2018 Eisteddfod was held in Cardiff Bay with a fence-free 'Maes'.

| National Eisteddfod Of Wales Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru | |

|---|---|

| |

A view of the Pafiliwn (Pavilion) for the 2003 National Eisteddfod, held at Meifod, Powys | |

| Status | Active |

| Genre | Cultural, music, poetry |

| Frequency | 1st week of August |

| Location(s) | Multiple (2019-Conwy County) |

| Country | |

| Established | 1861 |

| Participants | 6,000 |

| Attendance | 160,000 |

| Website | eisteddfod eisteddfod |

| 1 The festival has occasionally been held in England in the past. | |

History

The National Museum of Wales says that "the history of the Eisteddfod may [be] traced back to a bardic competition held by the Lord Rhys in Cardigan Castle in 1176",[3] and local Eisteddfodau have certainly been held for many years prior to the first national Eisteddfod. There have been multiple Eisteddfodau held on a national scale in Wales, such as the Gwyneddigion Eisteddfod of 1789, the Provincial Eisteddfodau from 1819–1834,[4] and the Abergavenny Eisteddfodau of 1835 to 1851,[5][6][7] and The Great Llangollen Eisteddfod of 1858,[8] but the National Eisteddfod of Wales as an organisation traces its history back to the first event held in 1861, in Aberdare.[9][10]

One of the most dramatic events in Eisteddfod history was the award of the 1917 chair to the poet Ellis Humphrey Evans, bardic name Hedd Wyn, for the poem Yr Arwr (The Hero). The winner was announced, and the crowd waited for the winner to stand up to accept the traditional congratulations before the chairing ceremony, but no winner appeared. It was then announced that Hedd Wyn had been killed the previous month on the battlefield at Passchendaele in Belgium. These events were portrayed in the Academy Award nominated film Hedd Wyn.

In 1940, during the Second World War, the Eisteddfod was not held, for fear that it would be a bombing target. Instead, the BBC broadcast an Eisteddfod radio programme, and the Chair, Crown and a Literature Medal (as opposed to the usual Prose Medal) were awarded.[11]

In 1950 a new rule was created that required all competitions to be held in Welsh. However, settings of the mass in Latin are allowed and this has been controversially used to allow concerts featuring international soloists.[12]

In recent years efforts have been made to attract more non-Welsh speakers to the event, with the officlal website stating "everyone is welcome at the Eisteddfod, whatever language they speak". The Eisteddfod offers bilingual signage and simultaneous-translation of many events though wireless headphones. There is also a Welsh-learners area called Maes D. These efforts has helped increase takings, and the 2006 Eisteddfod reported a profit of over £100,000, despite costing £2.8m to stage. The Eisteddfod attracts some 160,000 people annually. The National Eisteddfod in Cardiff (2008) drew record crowds, with over 160,000 visitors attending.

It was proposed that the 2018 National Eisteddfod in Cardiff would use permanent buildings to host events rather than in the traditional Maes site and tents. This was due partially to a lack of suitable land that could be repaired affordably after the festival. It was billed as an "Eisteddfod with no fence" in the media and was held at Cardiff Bay.[13][14][15] The 2019 Eisteddfod in Llanrwst returned to the traditional Maes.

The 2020 Eisteddfod was postponed for 12 months because of the international Covid-19 pandemic. This was the first year an Eisteddfod hadn't taken place since 1914, when the event was cancelled at short notice because of the outbreak of the Great War.[16]

Attendance

(incomplete)

| year | total attendance | profit/loss |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 144,220 | - |

| 2003 | 176,402 | |

| 2004 | 147,785 | - |

| 2005 | 157,820 | - |

| 2006 | 155,437 | +£100,000 |

| 2007 | 154,944[17] | +£4,324[18] |

| 2008 | 156,697 | +£38,000[19] |

| 2009 | 164,689 | +£145,000[20] |

| 2010 | 136,933[21] | -£47,000[20] |

| 2011 | 148,892[22] | -£90,000[20] |

| 2012 | 138,767[23] | +£50,000 |

| 2013 | 153,704[22] | +£76,000 |

| 2014 | 143,502 | +£90,000 |

| 2015 | 150,776 | +£54,721[24] |

| 2016 | 140,229 | +£6,000[25] |

| 2017 | 147,498 | +£93,200[26] |

| 2018 | ~500,000 | -£290,000[27] |

| 2019 | 150,000 | -£158,982[28] |

Overview

The National Eisteddfod is traditionally held in the first week of August, and the competitions are all held in the Welsh language. However, settings of the mass in Latin are allowed and this has been controversially used to allow concerts featuring international soloists.[29]

The venue is officially proclaimed a year in advance, at which time the themes and texts for the competitions are published. The organisation for the location will have begun a year or more earlier, and locations are generally known two or three years ahead. The Eisteddfod Act of 1959 allowed local authorities to give financial support to the event. Traditionally the Eisteddfod venue alternates between north and south Wales; the decision to hold both the 2014 and 2015 Eisteddfodau in South Wales was thus seen as controversial,[30] but the decision was later reversed and Montgomeryshire named as host county for 2015.[31] Occasionally the Eisteddfod has been held in England, although the last occasion was in 1929.[9]

Hundreds of tents, pavilions and booths are erected in an open space to create the Maes (field). The space required for this means that it is rare for the Eisteddfod to be in a city or town: instead it is held somewhere with more space. Car parking for day visitors alone requires several large fields, and many people camp on the site for the whole week.

The festival has a quasi-druidic flavour, with the main literary prizes for poetry and prose being awarded in colourful and dramatic ceremonies under the auspices of the Gorsedd of Bards of the Island of Britain, complete with prominent figures in Welsh cultural life dressed in flowing druidic costumes, flower dances, trumpet fanfares and a symbolic Horn of Plenty. However, the Gorsedd is not an ancient institution or a pagan ceremony but rather a romantic creation by Iolo Morganwg in the 1790s, which first became a formal part of the Eisteddfod ceremonial in 1819.[3] Nevertheless, it is taken very seriously, and an award of a crown or a chair for poetry is a great honour. The Chairing and Crowning ceremonies are the highlights of the week, and are presided over by the Archdruid. Other important awards include the Prose Medal (first introduced in 1937).

If no stone circle is there already, one is created out of Gorsedd stones, usually taken from the local area. These stone circles are icons all across Wales and signify the Eisteddfod having visited a community. As a cost-saving measure, the 2005 Eisteddfod was the first to use a temporary "fibre-glass stone" circle for the druidic ceremonies instead of a permanent stone circle. This also has the benefit of bringing the Gorsedd ceremonies onto the maes: previously they were often held many miles away, hidden from most of the public.

As well as the main pavilion with the main stage, there are other venues through the week. Some are fixtures every year, hosting gigs (Maes B/Llwyfan y Maes/Caffi Maes B). Other fixtures of the maes are the Pabell Lên (literature pavilion), the Neuadd Ddawns (dance hall), the Pabell Wyddoniaeth a Thechnoleg (science and technology pavilion), Maes D (learners' pavilion), at least one theatre, Y Cwt Drama (the drama hut), Tŷ Gwerin (folk house), Y Lle Celf ("the Art Place") and hundreds of stondinau (stands and booths) where groups, societies, councils, charities and shops exhibit and sell. Since 2004, alcohol has been sold on the maes; previously there was a no-alcohol policy.

Poetry awards

The Eisteddfod's most well-known awards are those for poetry.

Chairing of the Bard

Crowning of the Bard

Welsh-language album of the year

In 2014 the Eisteddfod began to award a Welsh-language Album of the Year (Albwm Cymraeg Y Flwyddyn) during its Maes B event.[32]

| Year | Winner |

|---|---|

| 2014 | The Gentle Good – Y Bardd Anfarwol[32] |

| 2015 | Gwenno – Y Dydd Olaf[33] |

| 2016 | Sŵnami – Sŵnami[34] |

| 2017 | Bendith – Bendith[35] |

| 2018 | Mellt – Mae’n Hawdd Pan ti’n Ifanc[36] |

National Eisteddfod venues

(Venues in England are in italics)

- 1861 – Aberdare

- 1862 – Caernarfon

- 1863 – Swansea

- 1864 – Llandudno

- 1865 – Aberystwyth

- 1866 – Chester

- 1867 – Carmarthen

- 1868 – Ruthin

- 1869 – Holywell

- 1872 – Tremadog

- 1873 – Mold

- 1874 – Bangor

- 1875 – Pwllheli

- 1876 – Wrexham

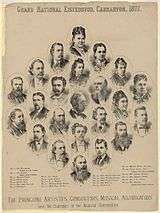

- 1877 – Caernarfon

- 1878 – Birkenhead

- 1879 – Conwy

- 1880 – Caernarfon

- 1881 – Merthyr Tydfil

- 1882 – Denbigh

- 1883 – Cardiff

- 1884 – Liverpool

- 1885 – Aberdare

- 1886 – Caernarfon

- 1887 – London Royal Albert Hall

- 1888 – Wrexham

- 1889 – Brecon

- 1890 – Bangor

- 1891 – Swansea

- 1892 – Rhyl

- 1893 – Pontypridd

- 1894 – Caernarfon

- 1895 – Llanelli

- 1896 – Llandudno

- 1897 – Newport

- 1898 – Blaenau Ffestiniog

- 1899 – Cardiff

- 1900 – Liverpool

- 1901 – Merthyr Tydfil

- 1902 – Bangor

- 1903 – Llanelli

- 1904 – Rhyl

- 1905 – Mountain Ash

- 1906 – Caernarfon

- 1907 – Swansea

- 1908 – Llangollen

- 1909 – London Royal Albert Hall

- 1910 – Colwyn Bay

- 1911 – Carmarthen

- 1912 – Wrexham

- 1913 – Abergavenny

- 1914 – Not held

- 1915 – Bangor

- 1916 – Aberystwyth

- 1917 – Birkenhead

- 1918 – Neath

- 1919 – Corwen

- 1920 – Barry

- 1921 – Caernarfon

- 1922 – Ammanford

- 1923 – Mold

- 1924 – Pontypool

- 1925 – Pwllheli

- 1926 – Swansea

- 1927 – Holyhead

- 1928 – Treorchy

- 1929 – Liverpool

- 1930 – Llanelli

- 1931 – Bangor

- 1932 – Aberavon

- 1933 – Wrexham

- 1934 – Neath

- 1935 – Caernarfon

- 1936 – Fishguard

- 1937 – Machynlleth

- 1938 – Cardiff

- 1939 – Denbigh

- 1940 – Mountain Ash, Radio Eisteddfod

- 1941 – Old Colwyn

- 1942 – Cardigan

- 1943 – Bangor

- 1944 – Llandybie

- 1945 – Rhosllannerchrugog

- 1946 – Mountain Ash

- 1947 – Colwyn Bay

- 1948 – Bridgend

- 1949 – Dolgellau

- 1950 – Caerphilly

- 1951 – Llanrwst

- 1952 – Aberystwyth

- 1953 – Rhyl

- 1954 – Ystradgynlais

- 1955 – Pwllheli

- 1956 – Aberdare

- 1957 – Llangefni

- 1958 – Ebbw Vale

- 1959 – Caernarfon

- 1960 – Cardiff

- 1961 – Rhosllannerchrugog

- 1962 – Llanelli

- 1963 – Llandudno

- 1964 – Swansea

- 1965 – Newtown

- 1966 – Aberavon

- 1967 – Bala

- 1968 – Barry

- 1969 – Flint

- 1970 – Ammanford

- 1971 – Bangor

- 1972 – Haverfordwest

- 1973 – Ruthin

- 1974 – Carmarthen

- 1975 – Criccieth

- 1976 – Cardigan

- 1977 – Wrexham

- 1978 – Cardiff

- 1979 – Caernarfon

- 1980 – Gowerton – Lliw Valley

- 1981 – Machynlleth

- 1982 – Swansea

- 1983 – Llangefni

- 1984 – Lampeter

- 1985 – Rhyl

- 1986 – Fishguard

- 1987 – Porthmadog

- 1988 – Newport

- 1989 – Llanrwst

- 1990 – Rhymney Valley

- 1991 – Mold

- 1992 – Aberystwyth

- 1993 – Llanelwedd

- 1994 – Neath

- 1995 – Abergele

- 1996 – Llandeilo (Ffairfach)

- 1997 – Bala

- 1998 – Bridgend (Pencoed)

- 1999 – Anglesey (Llanbedrgoch)

- 2000 – Llanelli

- 2001 – Denbigh

- 2002 – St David's

- 2003 – Meifod, near Welshpool

- 2004 – Newport

- 2005 – Faenol Estate, near Bangor

- 2006 – Swansea (Felindre)

- 2007 – Mold

- 2008 – Cardiff

- 2009 – Bala

- 2010 – Ebbw Vale[30][37][38]

- 2011 – Wrexham[30]

- 2012 – Llandow, Vale of Glamorgan[30]

- 2013 – Denbigh[30]

- 2014 – Llanelli

- 2015 – Meifod, near Welshpool

- 2016 – Abergavenny

- 2017 – Bodedern, Anglesey

- 2018 – Cardiff (Cardiff Bay)

- 2019 – Llanrwst

- 2020 - Not held / Postponed[39]

- 2021 – Tregaron

- 2022 – Boduan

- 2023 - Rhondda Cynon Taf

The Eisteddfod has visited all the traditional counties of Wales. It has visited five of the six cities in Wales: Bangor, Cardiff, Newport, St David's and Swansea; it has never visited St Asaph.

| County | 19th century | 20th century | 21st century | Total (1861–2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| 11 | 15 | 1 | 27 | |

| 1 | 6 | 0 | 7 | |

| 2 | 9 | 2 | 13 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| 4 | 14 | 3 | 21 | |

| 3 | 6 | 1 | 10 | |

| 8 | 24 | 3 | 35 | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 5 | 3 | 9 | |

| 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

References

- Williams, Sian. "Druids, bards and rituals: What is an Eisteddfod?". BBC. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Berry, Oliver; Else, David; Atkinson, David (2010). Discover Great Britain. Lonely Planet. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-74179-993-4.

- "History of the Welsh Eisteddfodau". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "The Provincial Eisteddfodau 1819-1834". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "The Abergavenny Eisteddfod | National Museum Wales". Museum.wales. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Welsh National Eisteddfodau". Genuki. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "History of the Welsh Eisteddfodau". National Museum Wales. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "The Great Llangollen Eisteddfod, 1858 | National Museum Wales". Museum.wales. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Past locations". National Eisteddfod of Wales. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "The Eisteddfod: 1861–1885". National Eisteddfod of Wales. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Lleoliad yr Eisteddfod: Eisteddfod Radio" (in Welsh). BBC. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Rhodri Clark. "Eisteddfod Latin in language loophole". Wales Online. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-07-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Eryl Crump (2017-06-25). "Hundreds parade for 2018 National Eisteddfod proclamation". Daily Post. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Thomas, Huw (2015-08-07). "National Eisteddfod considers ditching the Maes in 2018". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "How another crisis a century ago postponed the National Eisteddfod for the only other time in its history". North Wales Live. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- "Traders count cost of Eisteddfod". 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- Post, North Wales Daily (2008-07-01). "Eisteddfod work pays off with £4,000 profit". northwales. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- Post, North Wales Daily (2009-04-20). "Eisteddfod needs more cash ahead of Bala event". northwales. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- Crump, Eryl (2011-11-28). "National Eisteddfod in Wrexham makes £90k loss". northwales. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "EISTEDDFOD: Festival 'raised valleys' profile'". South Wales Argus. 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "National Eisteddfod 2015: The results from Friday". Wales Online. 2015-08-07. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "National Eisteddfod". Valeofglamorgan.gov.uk. 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Crump, Eryl (2015-11-28). "National Eisteddfod's iconic pink pavilion to be replaced". northwales. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- Crump, Eryl (2016-11-26). "National Eisteddfod 2016 was a 'cultural and financial success'". northwales. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- "National Eisteddfod 2019 in Llanrwst". BBC News. 2017-11-25. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- "National Eisteddfod 2019 in Llanrwst". BBC News. 2018-11-24. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- "The reason why National Eisteddfod 2019 made loss of more than £150,000". North Wales Live. 2019-11-23. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Rhodri Clark (2008-02-26). "Eisteddfod Latin in language loophole". Wales Online. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Prifwyl: Torri'r traddodiad symud?". BBC (in Welsh). 1 July 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Site for the Eisteddfod until 2016 at BBC Wales, 8 July 2010

- "The Gentle Good wins the Welsh Language Album of the Year prize". National Eisteddfod. 2014-08-07. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Albwm Cymraeg y Flwyddyn". National Eisteddfod. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Swnami win this year's Welsh Language Album of the Year". National Eisteddfod. 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Bendith win the Welsh Language Album of the Year Award". National Eisteddfod. 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Mellt yn ennill Albwm Cymraeg y Flwyddyn". golwg360.cymru. 9 August 2018.

- Delight over Eisteddfod 2010 plans at WalesOnline News, 14 August 2008

- Eisteddfod 2010 at the National Eisteddfod website

- "Ceredigion National Eisteddfod postponed for a year | National Eisteddfod". eisteddfod.wales.

- "Past locations". National Eisteddfod. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Eisteddfod of Wales. |

- Official website (in English)

- Official website (in Welsh)