Laie, Hawaii

Laie (Hawaiian: Lāʻie) is a census-designated place (CDP) located in the Koolauloa District on the island of Oahu (Oʻahu) in Honolulu County, Hawaii, United States. In Hawaiian, lāʻie means "ʻie leaf" (ʻieʻie is a climbing screwpine: Freycinetia arborea). The population was 6,138 at the 2010 census.[1]

Laie Lāʻie | |

|---|---|

The Laie Hawaii Temple, the fifth oldest LDS Church temple worldwide | |

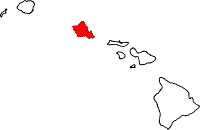

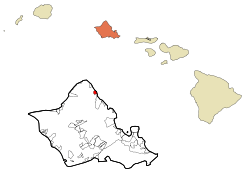

Location in Honolulu County and the state of Hawaii | |

| Coordinates: 21°38′55″N 157°55′32″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Hawaii |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.1 sq mi (5.5 km2) |

| • Land | 1.3 sq mi (3.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.9 sq mi (2.2 km2) |

| Elevation | 9 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,138 |

| • Density | 2,900/sq mi (1,100/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (Hawaii-Aleutian) |

| ZIP code | 96762 |

| Area code(s) | 808 |

| FIPS code | 15-43250 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0361691 |

History

Historically, Lāʻie was a puʻuhonua, a sanctuary for fugitives. While a fugitive was in the puʻuhonua, it was unlawful for that fugitive's pursuers to harm him or her. During wartime, spears with white flags attached were set up at each end of the city of refuge. If warriors attempted to pursue fugitives into the puʻuhonua, they would be killed by sanctuary priests. Fugitives seeking sanctuary in a city of refuge were not forced to permanently live within the confines of its walls. Instead, they were given two choices. In some cases, after a certain length of time (ranging from a couple of weeks to several years), fugitives could enter the service of the priests and assist in the daily affairs of the puʻuhonua. A second option was that after a certain length of time the fugitives would be free to leave and re-enter the world unmolested. Traditional cities of refuge were abolished in 1819.[2]

The history of Lāʻie began long before European contact. The name Lāʻie is said to derive from two Hawaiian words: lau meaning "leaf", and ʻie referring to the ʻieʻie (red-spiked climbing screwpine, Freycinetia arborea), which wreaths forest trees of the uplands or mauka regions of the mountains of the Koʻolau Range behind the community of Lāʻie. In Hawaiian mythology, this red-spiked climbing screwpine is sacred to Kāne, god of the earth, god of life, and god of the forests, as well as to Laka, the patron goddess of the hula.

The name Lāʻie becomes more environmentally significant through the Hawaiian oral history (kaʻao) entitled Laieikawai. In this history, the term ikawai, which means "in the water", also belongs to the food-producing tree called kalalaikawa. The kalalaikawa tree was planted in a place called Paliula's garden, which is closely associated with the spiritual home, after her birth and relocation of Laieikawai. According to Hawaiian oral traditions, the planting of the kalalaikawa tree in the garden of Paliula is symbolic of the reproductive energy of male and female, which union in turns fills the land with offspring. From its close association with nature through its name, and through its oral traditions and history, the community of Lāʻie takes upon itself a precise identification and a responsibility in perpetuating life and in preserving all life forms. Sometimes the land itself provided sanctuary for the Hawaiian people. Lāʻie was such a place. The earliest information about Lāʻie states that it was a small, sparsely populated village with a major distinction: "it was a city of refuge". Within this city of refuge were located at least two heiau, traditional Hawaiian temples, of which very little remains today. Moohekili heiau was destroyed, but its remains can be found in taro patches makai (seaward) of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints's (LDS Church) Laie Hawaii Temple. Towards the mountain (mauka), the remains of Nioi heiau can be found on a small ridge. All that is left of Nioi is a coral platform.[3]

Between 1846 and 1848, the traditional Hawaiian feudal ownership of land by the king, the aliʻi nui, and his leading chiefs or konohiki was changed through the Great Mahele, or major land division. The aliʻi nui at the time was Kauikeouli King Kamehameha III, and his konohiki (leading chief) for Lāʻie was Peni Kealiʻiwaiwaiole (which means "The Chief without Riches"); the wife to this konohiki descended directly from the aliʻi nui of Oʻahu named Kakuiewa, making his wife of higher rank than he. The result of the mahele was not in compliance with the original intent of Kamehameha III. The result was that the chiefs received about 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km2), the king kept about 1 million acres (4,000 km2), which were called crown lands, and about 1 million acres (4,000 km2) were set aside as government lands.

The land of the mahele itself was cut up into parcels, much like the traditional Hawaiian land divisions, centering on the ahupuaʻa, which followed a fairly uniform pattern. Each parcel was shaped roughly like a piece of pie with the tip in the mountains, the middle section in the foothills and coastal plain, and the broad base along the ocean front and the sea. The size and shape of the ahupuaʻa varied. However, the purpose of these remained the same. The village of Lāʻie is located in the ahupuaʻa of Lāʻie. As such, Lāʻie followed the general pattern of life in the ahupuaʻa, but only the valleys in the foothills had ample water. There were ten streams that flowed through the ahupuaʻa of Lāʻie before 1865 (see 1865 map). Their names were Kahooleinapea, Kaluakauila, Kahawainui, Kaihihi, Kawaipapa, Kawauwai, Wailele, Koloa, Akakii, and Kokololio. There were more streams flowing through the ahupuaʻa of Lāʻie than through any of the other surrounding ahupuaʻa, including Kaipapau and Hauula to the southeast and Malaekahana, Keana, and Kahuku to the northwest.

Latter-day Saints

A new phase of development for Lāʻie began when the plantation of that name was purchased by George Nebeker, the president of the Hawaiian Mission of the LDS Church. The Latter-day Saints in Hawaii were then encouraged to move to this location.[4] This purchase occurred in 1865.[5] The sugarcane plantation was rarely profitable, and through 1879 the church had subsidized its operations with about $40,000.[5]

Soon after the settlement a sugar factory was built. Much of the land was used to grow sugar, but other food crops were also raised. Significantly, Lāʻie was one of the few sugarcane plantations where both kalo (taro) and sugar were grown simultaneously. This was unusual because sugar and kalo are both thirsty crops. In the plantation economy of Hawaii in the late 19th century and early 20th century, kalo usually lost out to sugar. One of the reasons both kalo and sugar grew on the plantation is because of the commitment of Hawaiian plantation workers to growing their staple. Their dedication to growing kalo included their insistence that Saturday not be a work day on the plantation so that they could make poi for their families.[6] Both schools and church buildings were constructed in the town in the ensuing years.

Samuel E. Woolley, who served as mission president for 24 years, pushed the expansion of the operations at Laie. In 1898 he negotiated a $50,000 loan that allowed for the building of a new pump.[7]

The Hawaiian Mission was headquartered in Lāʻie until 1919 when the headquarters were moved to Honolulu, but by then the temple had been built in Lāʻie, so it remained the spiritual center of the Latter-day Saint community in Hawaii.[8]

Community

Lāʻie is one of the best known communities of the LDS Church and the site of the Laie Hawaii Temple, the church's fifth oldest operating temple in the world. Brigham Young University–Hawaii is located in Lāʻie. The Polynesian Cultural Center, the state's largest living museum, draws millions of visitors annually.[9][10]

Though small, Lāʻie has had a significant impact on Hawaiian culture, despite many of its residents' tracing their lineages from various Pacific Island countries such as Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, and New Zealand. Fundraisers and feasts on the beach in the late 1940s inspired "The Hukilau Song",[11] written, composed and originally recorded by Jack Owens, The Cruising Crooner, and made famous by Alfred Apaka.

Geography

Lāʻie is located at 21°38′55″N 157°55′32″W.[12] Lāʻie is located north of Hauula and south of Kahuku along Kamehameha Highway (State Route 83).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 2.1 square miles (5.4 km2). 1.3 square miles (3.4 km2) of it is land and 0.9 square miles (2.3 km2) of it (40.65%) is water.

The coastline is marked by Lāʻie Point, a prominent lithified dune jutting out into the ocean. Two other lithified dunes (Kukuihoolua and Mokualai) lie just offshore of the point as scenic islets. Lāʻie Beach Park was originally called Pahumoa Beach Park, after Pahumoa "John" Kamakeʻeʻāina (1879–1944), a fisherman from Lāʻie Maloʻo in the late 19th century and early 20th century who lived here and kept his nets on the beach adjacent to Kōloa Stream. He was well known in Lāʻie for his generosity and gave fish to everyone in the village, especially to those who could not fish for themselves. Pahumoa conducted many hukilau, a method of community net fishing.[13] His family, the Kamakeʻeʻāinas, were a well known fishing family in the area, and stories can still be found today of their abilities in fishing. To the south of town is Pounders Beach, named for the pounding shorebreak. The name change occurred in the 1950s, when a group of students at the Church College of the Pacific (now Brigham Young University–Hawaii) called the beach "Pounders" after the shorebreak that provided popular bodysurfing rides; the nickname stuck. Another bodysurfing beach is Hukilau, located at the north end of town, at the mouth of Kahawainui Stream.

Demographics

As of the census of 2000,[14] there were 4,585 people, 903 households, and 735 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 3,601.7 people per square mile (1,393.9/km2). There were 1,010 housing units at an average density of 793.4 per square mile (307.1/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 27.59% White, 0.35% Black or African American, 0.15% Native American, 9.23% Asian, 36.88% Pacific Islander, 0.65% from other races, and 25.15% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.12% of the population.

There were 903 households, out of which 46.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.2% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 18.6% were non-families. 9.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.47 and the average family size was 4.75.

In the CDP the population was spread out, with 31.8% under the age of 18, 21.8% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 14.5% from 45 to 64, and 5.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 24 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $50,875, and the median income for a family was $59,432. Males had a median income of $40,242 versus $26,750 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $13,785. About 10.7% of families and 17.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.8% of those under the age of 18 and 11.6% of those ages 65 and older.

Education

Lāʻie is within the Hawaii Department of Education. Lāʻie Elementary School is in the CDP.[15]

Notable people

- Joseph Kekuku (1874–1931), inventor of steel guitar

- Neff Maiava (1924–2018), professional wrestler

- Ken Niumatalolo (born 1965), head football coach, United States Naval Academy

- Keala Settle (born 1975), actress and singer

- Manti Te'o (born 1991), American football linebacker

- Roman Salanoa (born 1997), rugby union prop

- Liam Wilson (born 2002), professional surfer

References

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Laie CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Mulholland, John F. Hawaii's Religions. Rutland: Tuttle, 1970, p. 121

- Sterling & Summers 1978, p. 158

- Jenson, Andrew. Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1941) p. 324

- Mulholland, Hawaii's Religions, p. 122

- Compton, Cynthia (December 2005). "The Making of the Ahupuaa of Laie into a Gathering Place and Plantation, The Creation of an Alternative Space to Capitalism" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-28. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mulholland, Hawaii's Religions, p. 123

- Jenson. Encyclopedic History. p. 324

- Polynesian Cultural Center Official Site - Best Luau Oahu, Hawaii

- Theresa Bigbie (July 8, 2004). "Lai'e - A Sacred Privilege and Responsibility". devotional.byuh.edu. byuh.edu. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- History of the Hukilau Song Archived 2008-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Hawaii Place Names, Shores, Beaches, and Surf Sites" by John R. K. Clark, University of Hawaii Press, November 2001, Page 207, referring to Lahilahi Point and the LaMariana Sailing Club. As well as "Beaches of Oʻahu, Revised Edition" by John R. K. Clark, University of Hawaii Press, 2004, page 91. Reference information annotated with updated information from the Kamakeʻeʻāina family genealogical data by Kāwika Kolomona Kamakeʻeʻāina, great-great grandson of Pahumoa "John" Kamakeʻeʻāina.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Laie CDP, Hawaii." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

Further reading

- Aikau, Hokulani K. (Winter 2008). "Resisting Exile in the Homeland: He Moʻolemo No Lāʻie". American Indian Quarterly. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 32 (1): 70–95. doi:10.1353/aiq.2008.0003. ISSN 0095-182X.

- Dorrance, William H. (1998). Oʻahu's Hidden History: Tours into the Past. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing. ISBN 1-56647-211-3.

- Sterling, Elspeth P.; Catherine C. Summers (1978). Sites of Oahu. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. pp. 155–160. ISBN 0-910240-73-6.

- Moffat, Riley (1997). Historical Sites Around Laʻie. Lāʻie: Mormon Pacific Historical Society.