French immigration to Puerto Rico

French immigration to Puerto Rico came about as a result of the economic and political situations which occurred in various places such as Louisiana (United States), Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and in Europe.

| French immigration to Puerto Rico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

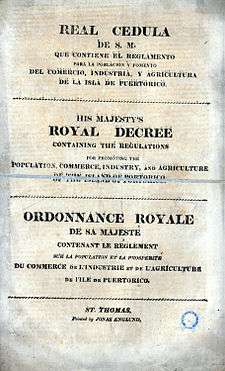

Other important factors which encouraged French immigration to the island was the revival of the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 in the later 19th century.

The Spanish Crown decided that one of the ways to discourage pro-independence movements in Puerto Rico (and Cuba) was to allow Europeans who were not of Spanish origin and who swore loyalty to the Spanish Crown to settle in the island. Therefore, the decree was printed in three languages: the Spanish language, the English language, and the French language and circulated widely through ports and coastal cities throughout Europe.

The French who immigrated to Puerto Rico quickly became part of the Island immigrant communities, which were predominantly Catholic also. They settled in various places in the island. They were instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's tobacco, cotton and sugar industries and distinguished themselves as business people, merchants, tradesmen, politicians and writers.

Situation in Louisiana

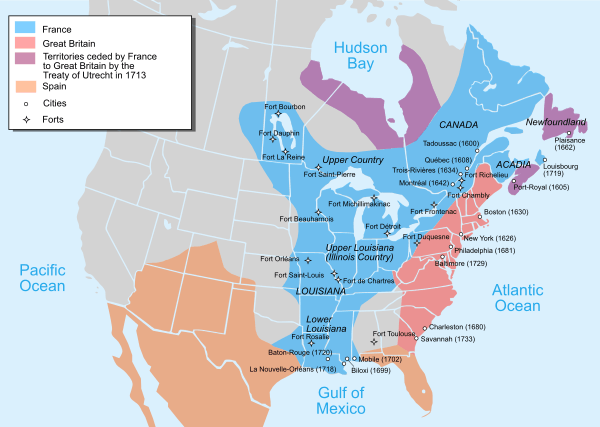

In the 17th century, the French settled an area of North America in what was then referred to as the "New World" which they named New France.

New France included an expansive area of land along both sides of the Mississippi River between the Appalachian Mountains and the Rocky Mountains, including the Ohio Country and the Illinois Country.

"Louisiana" was the name given to an administrative district of New France.[1] Upon the outbreak of the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years' War (1754–1763), between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its North American Colonies against France.

Many of the French settlers fearing the English-speaking intruders who were invading the former French and Spanish territory of Louisiana fled to the Caribbean islands of Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Puerto Rico to re-establish their commercial, trading and agricultural enterprises.

These islands were part of the Spanish and New World Catholic Empire, which welcomed and protected the French from their English and Protestant enemy.[2]

Frenchmen in the defense of Puerto Rico

When the British attempted to invade Puerto Rico in 1797 under the command of Sir Ralph Abercromby, many of the newly arrived French immigrants offered their services to the Spanish colonial government in Puerto Rico in defense of the Island that had taken them in when they fled from the Louisiana "Territory" of the United States.

Among them was Corsair Captain and former Royal Naval officer of the French Navy, Capt. Antoine Daubón, owner and captain of the ship "L'Espiégle" and another Frenchman named Captain Lobeau of the ship "Le Triomphant". Capt. Daubón, who had acquired a "Letter of Marque" from France was in the San Juan Bay area after having captured the American ship "Kitty", of Philadelphia, and was holding captive a crew of American soldiers.

French Capt. Daubón, son of Jacobin French Revolutionary activist, Raymond Daubón, was one of three registered corsairs in the Caribbean's Commercial Tribunal of Basse-Terre, Guadaloupe, licensed to seize and capture enemy vessels on behalf of France.

Daubón offered his services and the use of his vessel and men to the Spanish Colonial Governor of Puerto Rico and together with the French Consul on the island, M. Paris, gathered a group of French immigrants in Puerto Rico and sent these troops to successfully protect the entrance of San Juan at Fort San Gerónimo. Among the French surnames of those who fought on the Island were: Bernard, Hirigoyan, Chateau, Roussell, Larrac and Mallet. It is also worthy of note to mention that the British attempted to land in San Juan harbor with a force of 400 French prisoners, who were forced to fight against their will the other French troops defending Puerto Rico.

French Consul M. Paris, sent a letter addressed to the French soldiers being forced to fight for England, promising them a safe haven in San Juan which was signed by Governor Castro.

Due in part to this successful effort, the British forces were further weakened when the French prisoners agreed to accept the offer from the French Consul in Puerto Rico and become settlers on the Island.[3][4]

The English invasion quickly floundered and the British retreated on April 30, from the Island to their ships and on May 2, set sail northward out of San Juan Harbor without their 400 French prisoners, who were to become part of the already established immigrant French community in Puerto Rico.

These Frenchmen were immediately accepted and joined the other French immigrants who also had fought against the English invasion with the French prisoners. The newly arrived 400 Frenchmen all stayed and thrive in Puerto Rico. They soon sent for their families who were living in France.

The descendants of these 18th century French immigrant arrivals in Puerto Rico and their families continued as those before them to quickly establish themselves as tradesmen, merchants, traders, community leaders and established innumerable entrepreneurial enterprises with France and other French colonial trading ports and today continue to live in Puerto Rico where they have distinguished themselves among all the aspects of Puerto Rican Insular life.[4]

Haitian Revolution

In 1796, the Spanish Crown ceded the western half of the island of Hispaniola to the French. The Spanish part of the island was named Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) and the French named their part Saint-Domingue (which was later renamed Haiti). The French settlers dedicated themselves to the cultivation of the sugar cane and owned plantations, which required a huge amount of manpower. They enslaved and imported people from Africa to work in the fields. However, soon the population of the enslaved outgrew those of the colonizers. The enslaved lived under terrible conditions and were treated cruelly. In 1791, the enslaved African people were organized into an army led by General Toussaint L'Ouverture who rebelled against the French in what is known as the Haitian Revolution.[5] The ultimate victory of the enslaved over their white colonizing masters came about after the Battle of Vertières in 1803. The French fled to Santo Domingo and made their way to Puerto Rico. Once there, they settled in the western region of the island in towns such as Mayagüez. With their expertise, they helped develop the island's sugar industry, converting Puerto Rico into a world leader in the exportation of sugar.[6]

Settling in Puerto Rico

A Frenchmen who escaped from then-Saint-Domingue was Dr. Luis Rayffer. Rayffer first lived in Mayagüez and in 1796 moved to the town of Bayamón where he established a prosperous coffee plantation.[7]

Juan Bautista Plumey came from Haiti with some slaves and married a woman from San Sebastián. In 1830 he established a coffee hacienda and by 1846, Plumey's hacienda which at the time was called Hacienda La Esperanza, and later called Hacienda Lealtad, "was the only property labeled as an hacienda in official documents. He had 69 cuerdas planted in coffee worked by 33 slaves."[8] Plumey did not allow his workers to work on any other farm.[9][10]

Among the families who settled in Puerto Rico were the Beauchamps. Francois Joseph Beauchamp Menier, from St. Nazaire, France, was a member of the French Army stationed in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) with his family during the Haitian revolution. When the French ranks were disbanded he boarded a ship bound for Martinique, together with his wife Elizabeth Sterling and children. The boat however ran ashore in Puerto Rico instead of reaching Martinique. The Spanish government offered Beauchamp Menier land to cultivate and the family settled in the town of Añasco.

The family had thirteen children, including those who were born in Saint-Domingue (Santo Domingo, today). It is believed that all of the Beauchamps in Puerto Rico are descendants of Francois Joseph Beauchamp Menier and Elizabeth Sterling.[11] The Beauchamp family was active in Puerto Rican politics. Among the notable members of this family are Eduvigis Beauchamp Sterling, named Treasurer of the revolution against Spanish colonial rule known as El Grito de Lares by Ramón Emeterio Betances. He was the person who provided Mariana Bracetti with the materials for the Revolutionary Flag of Lares. Pablo Antonio Beauchamp Sterling was a principal leader of the Mayagüez cell during the Lares Revolution. In the early 20th century another member of the family was an active member of the Puerto Rican independence movement, he was Elías Beauchamp, a member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party who assassinated Colonel Francis Riggs in 1936 in retribution of the events of the Río Piedras massacre. Carlos María Beauchamp Giorgi served as Mayor of Las Marias and Ramón Beauchamp Gonzáles was the Secretary of the Senate in 1916.[11]

Situation in Europe

France and Corsica (an island ceded to France by Genoa in 1768) were going through many economic and political changes during the 19th century.

One of the changes occurred with the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution, which led to the massive migration of farmworkers to larger cities in search of a better way of life and better-paying jobs. Starvation spread throughout Europe as farms began to fail due to long periods of drought and crop diseases.[12]

There was also widespread political discontent. King Louis-Philippe of France was overthrown during the Revolution of 1848 and a republic was established. In 1870–71, Prussia defeated France in what became known as the Franco-Prussian War. The combination of natural and man-made disasters created an acute feeling of hopelessness in both France and Corsica. Hundreds of families fled Europe and immigrated to the Americas, including Puerto Rico. All of this came about when the Spanish Crown, after losing most of her possessions in the so-called "New World", was growing fearful of the possibility of losing her last two possessions, Cuba and Puerto Rico.[13]

Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

In 1815, the Spanish Crown had issued a Royal Decree of Graces (Real Cédula de Gracias) with the intention of encouraging more commercial trade between Puerto Rico and other countries who were friendly towards Spain. This economic strategy directed at all of Europe and its colonies in the New World in the Caribbean, North, Central and South America.

The decree also offered free land to any Spaniard who would be willing to settle on the island and establish commercial and agricultural enterprises, i.e. plantations, farms and business that reached-out to other colonies.

In the mid-1800s, the decree was revised with many more immigrant-friendly enhancements which invited immigration for other non-Spanish-speaking European immigrants who were also Catholic.

The Spanish colonial governments did this, in an attempt to encourage settlers that would not be "pro-independence" and would show allegiance to Spanish colonial government. The newly revised decree now allowed all European immigrants of non-Spanish origin to settle the island of Puerto Rico. The decree was printed in three languages, Spanish, English and French and circulated throughout all of Europe, where there were already immigrant communities bound for the New World colonies.

Those who immigrated to Puerto Rico were given free land and a "Letter of Domicile" with the condition that they swore loyalty to the Spanish Crown and allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. Most of the new immigrants eventually were settled in the interior of the island which was mostly undeveloped. After residing in the island for five years these European settlers were granted a "Letter of Naturalization" which made them Spanish subjects.[14] Thousands of French and Corsican families (the Corsicans were French citizens of Italian descent) settled in Puerto Rico.

The cultural influence of the French which had already been making a cultural impact on the Island since the 1700s was further strengthened as evidenced by the construction in 1884 of one of Puerto Rico's grandest theater "El Teatro Francés" (The French Theater), was located on the Calle Méndez Vigo in the City of Mayagüez (the theater building was later destroyed by an earthquake).[15]

The Corsicans (who had Italian surnames) settled the mountainous region in and around the towns of Adjuntas, Lares, Utuado, Guayanilla, Ponce and Yauco, where they became successful coffee plantation owners. The French who immigrated with them from mainland France also settled in various places in the island, mostly in the unsettled interior regions of the Island, which up to that point were virtually uninhabited.

They were instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's tobacco, cotton and sugar industries. Among them was Teófilo José Jaime María Le Guillou who in 1823 founded the municipality of Vieques, Puerto Rico.[16]

French influence in Vieques

Teófilo José Jaime María Le Guillou Le Guillou was born in Quimperlé, France. He immigrated from France to the Island of Guadaloupe in the French West Indies where he became a land owner.[17]

In 1823, Le Guillou went to the island of Vieques with the intention of purchasing hardwoods. The island at the time had a few residents who were dedicated woodcutters. He was impressed with the island of Vieques and saw the agricultural potential of the island. He returned the following year and purchased lands from a woodcutter named Patricio Ramos. Soon, he established the largest sugar plantation on the island which he named "La Pacience". He then got rid of the pirates and those involved in contraband activities an action which in itself pleased the Spanish colonial government. Le Guillou is considered to be the founder of the municipality of Vieques.[17]

In 1832, Le Guillou proceeded Francisco Rosello as the military commander of Vieques after Rosello's death. Between 1832 and 1843, Le Guillou who had been given the title of "Political and Military Governor of the Spanish Island of Vieques" by the Spanish Crown, developed a plan for the political and economic organization of the island.[18] He established five sugar plantations in the island named Esperanza, Resolucion, Destino, Mon Repos and Mi Reposo.[19][17]

Le Guillou, who was the most powerful landlord and owner of slaves in the island, requested from the Spanish Crown permission to allow the immigration of French families from the Caribbean Islands of Martinique and Guadalupe which at the time were French possessions. Attracted by the offer of free land as one of the concessions stipulated in the revised Spanish Royal Decree of 1815, dozens of French familles, among them the Mouraille's, Martineau's and Le Brun's, immigrated to Vieques and with the use of slave manpower established sugar plantations.[18] By 1839, there were 138 "habitaciones" which comes from the French word "habitation" meaning plantation.[19] These habitaciones were located from Punta Mulas and Punta Arenas.[17]

Le Guillou died in 1843 and is buried in Las Tumbas de Le Guillou in Isabel Segunda, Vieques Municipality. The town of Isabel II of Vieques was founded in 1844.[19] His wife Madame Guillermina Ana Susana Poncet died in 1855 and is buried alongside Le Guillou.[17] The cemetery where Le Guillou and his wife are buried was officially named "Las Tumbas de J. J. María le Guillou" by the United States Department of the Interior and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in August 26, 1994, reference #94000923.

French influence in Puerto Rican and popular culture

The French, who had been arriving on the Island since the 1700s, quickly became part of the Spanish colonial community.

They accomplished this by quickly establishing commercial and social connections with the already prospering Spanish settlers and marrying into the ever-increasingly successful Spanish-descended families, adopting the Spanish language and all Ibero-European customs of their new homeland, that they already had familiarity with in France.[20]

Their influence in Puerto Rico is very much present and in evidence in the island's cuisine, literature and arts.[21]

French surnames are common in Puerto Rico. This prolonged immigration flow from mainland France and its Mediterranean territories (especially Corsica) to Puerto Rico was the largest in number, second only to that of the steady flow of Peninsular Spanish immigrants from mainland Spain and its own Mediterranean and Atlantic Maritime provinces of Mallorca and the Canary Islands.

Today, the great number of Puerto Ricans of French ancestry are evident in the 19% of family surnames on the island that are of French origin. These are easily traceable to mainland France, French Louisiana émigrés, and other French colonies in the Caribbean which experienced catastrophic slave upheavals that forced the French colonists to flee.

The descendants of the original French settlers have distinguished themselves as business people, politicians and writers. "La Casa del Francés" (The Frenchman's House), built in 1910, is a turn-of-the-century plantation mansion recently designated as a historical landmark by the National Register of Historic Places. It is located on the island of Vieques and is currently used as a guest house.[22]

Besides having distinguished careers in agriculture, the academy, the arts and the military, Puerto Ricans of French descent have made many other contributions to the Puerto Rican way of life. Their contributions can be found, but are not limited to, the fields of education, commerce, politics, science and entertainment.

Among the poets of French descent who have contributed to the literature of Puerto Rico are Evaristo Ribera Chevremont, whose verses are liberated from folkloric subject matter and excel in universal lyricism,[23] José Gautier Benítez, considered by the people of Puerto Rico to be the best poet of the Romantic Era,[24] the novelist and journalist Enrique Laguerre, a nominee for a Nobel Prize in literature,[25] and writer and playwright René Marqués, whose play La Carreta (The Oxcart) helped secure his reputation as a leading literary figure in Puerto Rico. The drama traces a rural Puerto Rican family as it moved to the slums of San Juan and then to New York in search of a better life, only to be disillusioned and to long for their island.[26]

In the field of science Dr. Carlos E. Chardón, the first Puerto Rican mycologist, is known as "the Father of Mycology in Puerto Rico". He discovered the aphid "Aphis maidis", the vector of the sugar cane Mosaic virus. Mosaic viruses are plant viruses.[27] Fermín Tangüis, an agriculturist and scientist developed the seed that would eventually produce the Tangüis cotton in Peru, saving that nation's cotton industry.[28]

Surnames

The following is an official (but not complete) list of the surnames of the first French families who immigrated from mainland France to Puerto Rico in the 19th century.

This additional list (below) was compiled by genealogists and historians of Proyecto Salon Hogar who have done an exhaustive research on the matter.[29]

| Surnames of the first French families in Puerto Rico | ||||

| Abesto, Abre Resy, Affigne, Affrige, Agapit, Agrand, Albet, Alegre, Alers, Alexo, Alfonso, Allinor, Ambar, Ambies, Amil, Andragues, Andrave, Anduze, Anglada, Angur, Aran, Ardu, Arnaud, Arril, Artaud Herajes, Auber, Aymee, Bablot, Baboan, Bacon, Bainy, Balsante Petra, Baner, Bapeene, Bargota Boyer, Baron, Barrera, Bassat, Baux, Baynoa, Beabieu, Beauchamp, Beaupied, Begonguin, Beinut, Belnar, Beltran, Belvi, Bellevue, Benevant, Benito, Berantier, Bergonognau, Bernal Capdan, Bernard, Bernier, Berteau, Bertrand, Betancourt, Bicequet, Bidot, Bignon, Binon, Binot, Bitre, Blain, Blanchet, Blaudin, Blondet, Boirie, Boldnare, Bollei, Bonafoux Adarichb, Bonch, Bonifor, Bontet, Bordenare, Boreau Villoseatj, Borras, Bosan, Botreau, Boudens, Boudovier Bertran, Bougeois, Boulet, Boulier, Boullerie, Boure, Bourjae, Boyer, Boyse, Boyset, Braschi, Brayer, Brevan, Brison, Broccand, Brochard, Brun, Bruny, Bruseant, Brusso, Bueno, Bufos, Bugier, Buis, Bulancie, Bullet, Burbon, Buriac, Burtel, Busquets, Cachant, Calmelz, Callasee, Cambet, Camelise, Camoin, Camy, Capifali, Cappdepor, Carbonell, Cardose, Carile, Carle, Caro, Casado Jafiet, Casadomo, Catalino, Catery Judikhe Vadelaisse, Caumil, Caussade, Cayenne, Cecila, Cerce, Ciobren, Ciriaco, Clausell, Coillas, Coin, Combertier, Compared, Conde, Constantin, Coriel, Cottes Ledoux, Coulandres, Couppe, Cristy, Croix, Crouset, Cruzy Marcillac, Curet, Chadrey, Chamant, Chamanzel, Chansan, Chanvet, Charle, Charles, Chariot, Charpentier, Charron, Chasli, Chassereau or Chasserian, Chatel, Chatelan, Chavalier or Chevalier, Chavarnier, Chebri, Cherot, Chevalot, Chevremont, Chicatoy Arenas, Choudens, Dabey, Dacot, Daloz, Daltas, Dalvert, Dambe, Damelon, Dandelor, Danloits, Dapie, Datjbon Duphy, Daunies, Debornes, Debrat, Declet, Defontaine, Delange, Delarue, Delema or Delima, Delestre, Delmas or Delinas, Delorise, Denasps Gue, Denichan, Denis, Denton, Desaint, Desjardins, Despres, Desuze, Detbais, Deuview, Dodin Dargomet, Doisteau, Dollfus, Domincy, Domon, Donz, Doval, Dubine, Dubois, Dubost, Du-Croe, Dudoy, Dufan, Duffant, Duffrenet, Dufour, Dugomis, Duha or Dulia, Dumartray, Dumas, Dumestre, Dumont, Dupay, Duplesi, Dupont, Dupret, Durey, Durad, Duran, Durant, Durecu, Durecu Hesont, Durruin, Duteil, Dutil, D'Yssoyer, Eduardo, Eilot, Eitie, Enrique Ferrion, Enscart, Escabi, Escache or Escachi, Escott, Esmein, Espiet, Espri Saldont, Faffin Fabus, Faja, Falasao or Tasalac, Falist Oliber, Farine De Rosell, Farrait, Faulat Palen, Feissonniere, Ferrer, Ferry Pelieser, Ficaya, Fineta, Fleuricun, Fleyta 0 Fleyeta, Fol, Follepe, Foncarde, Fongerat, Fontan, Forney, Francolin, Frene, Froger, Furo, Garie, Garo or Laro, Gaspierre, Gaston, Gautier, Georgatt, Gevigi, Gineau, Giraldet, Giraud, Girod, Girod Danise, Glaudina Godreau, Golbe, Gonzaga, Gonzago, Goriel, Goulain Jabet, Gregori, Gremaldi, Greton, Grivot, Grolau or Grolan, Guestel, Gueyt, Gullie or Gille Forastier, Guillon, Guillot, Guinbes, Guinbon, Guuiot, Guinot, Gure, Habe, Hardoy Laezalde, Hilario or Ylario, Hilnse, Hory, Hubert Chavaud, Icaire, Ithier, Jayaoan De Roudier, Joanel, Jourdan, Jovet, Juliana, Julien, Kercado, Kindell, LaRue, LaSalle, Labaden Laguet, Labault De Leon, Labergne or Labergue, Labord, Laboy, Lacode or Lecode, Lacon, Lacorte, Lacroix, Lafalle, Lafebre, Laffch, Lafont De La Vermede, Lafountain, Laguerre, Laporet, Lagar Daverati, Lagarde, Lairguat, Lalane, Lambert Beniel, Lamida, Lamond, Landrami, Landro, Lang, Lantiao, Lapierre, Laporte, Larbizan, Larohe, Larracontre, Larrony or Labrouy, L'Artigaut, Lasy or Lasey, Lasenne, Lassere, Lassise, Laugier, Lavergne, Laveiere or Lavesier, Layno, Lazus, Le Guillou, Lebron, Lebrum, Ledaut, Ledir or Lediz, Ledoux, Lefaure, Lefebre, Lefran, Legran, Legre, Le Guillon, Lelon, Lesirges, Libran, Liciz Getas, Logellanercies, Lombarda, Longueville, Loubet, Loubriel, Lourent or Saint Lourent, Lubes, Luca, Luca O'Herisson, Luis, Maillet, Malaret, Marqués, Malerve, Mande, Mange, Maoy, Marciel, Mareaty, Maren, Maria, Martel Belleraoch, Martilly, Martin, Mase, Mates Caslbol, Maturin, Mayar, Mayer, Mayostiales, Maysonave, Meaux, Medar, Menases, Mengelle, Mentrie, Merced, Micard, Michar Sibeli or Libeli, Michet, Midard Garrousette, Miguncci, Millet, Miyet, Moget, Molier, Moncillae, Monclova, Mondear, Monge, Monroig, Mons, Montas, Montrousier, Morell, Moret, Morin, Mosenp or Moreno, Mouliert, Moulinie, Mourei, Moysart, Misteau or Msiteau Chevalier, Naclero or Nadero, Nairsteant, Neaci, Nevi, Nod or Noel, Nogues, Noublet, Nunci, Nurez, Oclave, Odeman, Odiot, Ogea, Oliney, Orto, Oschembein, Osoglas, Panel, Paret, Parna, Patterne, Paulin Cesuezon, Pedangais, Pedevidou, Perrosier, Petit, Pepin, Peyredisu, Pibalan, Pilagome, Piletti, Pilioner, Pinaud Marchisa, Pinaud Marquisa, Pinplat or Puiplat, Pipau, Pitre, Plumet, Plumey, Poigmirou, Polok, Pomes, Ponteau, Porrata Doria, Posit, Potier Defur, Pouyolk, Pras, Preagnard, Preston, Principe Boussit, Privat, Pujols, Punan Sordeau, Raff, Ramel, Raplis De Pierrugues, Raty Menton, Raymond, Regnaire or Reguaire, Regnan, Reis, Reive, Renuchi, Resu, Rey, Richard, Rined De Boudens, Rinire, Rirwan, Riset, Ritter, Rivier, Roberson, Robiens, Robledo, Roblin, Rochette, Ronde, Ronse or Rouse, Rormi or Piormi, Roudier, Rous, Rousset, Roy, Royer, Rufait, Ruffin, Sabatel Mariel, Sabathie, Saladin, Salcedo, Saldri or Saldu, Saleinon, Sallaberry, Samanos, Saneburg, Sanlecque Botle, Sanocouret, Sansous, Sante Ylaide or Haide, Santeran, Santerose, Santie or Santiecor, Sapeyoie, Satraber, Saunion, Savignat Bruchat, Schabrie, Seguinot, Segur, Sellier, Sena Feun Fewhet, Senac De Laforest, Serracante Cacoppo, Simon Poncitan, Simonet, Sofi Mase, Sotier, Souche, Souffbont, Souffront, Soutearud, Stefani, Steinacher, Stucker, Suquet, Tablas, Tafa, Taret, Taura or Faura, Teanjou, Teber, Teissonniere, Telmo Navarro, Tellot, Terrefor, Terrible, Terrior, Thillet, Tibaudien, Timoleon, Tinot, Tolifru, Tollie, Tomet, Tomey, Totti, Tourne or St. Tounne, Tourne, Trabesier, Traver, Turpeand or Turpeaud, Umosquita, Ursula, Vanel, Veuntidos, Verges, Viado, Vignalon, Vignon, Villanueva, Vilencourt, Villard, Vigoreaux, Vizco, Vodart, Vora Bonel, Walleborge, Yarden or Garden, Ybar, Ylario, Yorde or Forte Godiezu, Yormie, Yuldet, Zanti | ||||

See also

References

| Part of a series on |

| Puerto Ricans |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Subgroups |

| Culture |

| Religion |

|

| Language |

|

|

- New France

- Historical Preservation Archive: Transcribed Articles & Documents

- Andre Pierre Ledru, Voyage Aux Les Iles de Tenerife, La Trinite, St. Thomas, St. Croix et Porto Rico; p. 135

- ""Historia de Puerto Rico" de Paul G. Miller, Rand McNally, editor, 1947, pp. 221–237". Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography by J. R. Beard, 1863

- The Haitian Revolution Archived August 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Cuaderno Histórico de Bayamón"; Page 20; Publisher: Instituto de Historia y Cultura Municipio de Bayamón – 1983

- Bergad, Laird W. (May 25, 1983). "Coffee and Rural Proletarianization in Puerto Rico, 1840-1898". Journal of Latin American Studies. 15 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00009573. JSTOR 155924.

- James Alexander Robertson (1980). The Hispanic American Historical Review. Board of Editors of the Hispanic American Review.

- "La esclavitud en Puerto Rico: inicios, desarrollo y abolición" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "Beauchamp family". Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- Second Industrial Revolution in France by Hubert Bonin, Retrieved July 31, 2007

- Documents of the Revolution of 1848 in France, Retrieved July 31, 2007

- Archivo General de Puerto Rico: Documentos Archived October 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Puerto Rico, Then And Now", by: Jorge Rigau, page 26, ISBN 978-1-59223-941-2

- Puerto Rico por Dentro

- "United States Department of the Interior National Park Service" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- Enlaces de Vieques (Spanish)

- "Guias para el Desarollo Sustentable de Vieques" (Spanish), By Grupo de Apoyo Tecnicos y Profesionales, Special Commission on Vieques, Pg.5

- Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico Archived February 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved July 31, 2007

- Puerto Rican Cuisine & Recipes

- NOTES FROM THE FORT MUSEUM

- Evaristo Ribera Chevremont: Voz De Vanguardia by Marxuach, Carmen Irene

- El Nuevo Dia Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Rossello, Hernandez Colon, Ferre Urge Nobel Prize in Literature for Enrique Laguerre Associated Press. March 3, 1999

- An Analysis of “The Oxcart” by René Marqués, Puerto Rican Playwright

- Archivo General de Puerto Rico: Documentos Archived October 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved August 3, 2007

- Los Primeros años de Tangüis Archived February 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Historia de Puerto Rico En orden afabético, Retrieved January 20, 2009

External links

- 19th century French Politics

- French influence in Puerto Rican cuisine

- National Register of Historic Places