Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in West Yorkshire, England, near the A1 (or Great North Road) and the M62 motorway. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the five towns in the metropolitan borough of the City of Wakefield and had a population of 30,881 at the 2011 Census.[1][2] Pontefract's motto is Post mortem patris pro filio, Latin for "After the death of the father, support the son", a reference to the English Civil War Royalist sympathies.[3]

| Pontefract | |

|---|---|

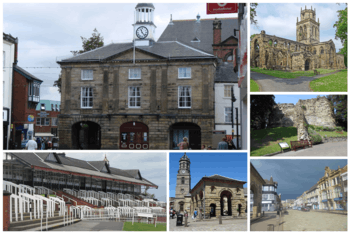

Pontefract. (from top left working clockwise); Old Town Hall, All Saints' Church, Pontefract Castle, Market Place, St Giles' Church and the Buttercross, Pontefract Racecourse. | |

Pontefract Location within West Yorkshire | |

| Population | 30,881 (North+South Wards 2011) |

| OS grid reference | SE455215 |

| • London | 257 mi (414 km) |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PONTEFRACT |

| Postcode district | WF8 |

| Dialling code | 01977 |

| Police | West Yorkshire |

| Fire | West Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament | |

Etymology

At the end of the 11th century, the modern township of Pontefract consisted of two distinct and separate localities known as Tanshelf and Kirkby.[4] The 11th-century historian, Orderic Vitalis, recorded that, in 1069, William the Conqueror travelled across Yorkshire to put down an uprising which had sacked York, but that, upon his journey to the city, he discovered that the crossing of the River Aire at what is modern-day Pontefract had been blockaded by a group of local Anglo-Scandinavian insurgents, who had broken the bridge and held the opposite bank in force.[5] Such a crossing point would have been important in the town's early days, providing access between Pontefract and other settlements to the north and east, such as York.[6] Historians believe that, in all probability, it is this historical event which gives the township of Pontefract its modern name. The name "Pontefract" originates from the Latin for "broken bridge", formed of the elements pons ('bridge') and fractus ('broken'). Pontefract was not recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book, but it was noted as Pontefracto in 1090, four years after the Domesday survey.[7]

History

Neolithic

In 2007 a suspected extension of Ferrybridge Henge – a Neolithic henge – was discovered near Pontefract during a survey in preparation for the construction of a row of houses. Once the survey was complete, the construction continued.[8]

Roman

The modern town is situated on an old Roman road (now the A639), described as the "Roman Ridge", which passes south towards Doncaster. The Roman Ridge is believed to form part of an alternative route from Doncaster to York via Castleford and Tadcaster, as a diversion of the major Roman road Ermine Street, which may have been used to avoid having to cross the River Humber near North Ferriby during rough weather conditions over the Humber.

Anglo-Scandinavian history

The period of Yorkshire's history between the demise of the Viking king Eric Bloodaxe in 954 and the arrival of the Normans in 1068 is known as the Anglo-Scandinavian age. The modern township of Pontefract consisted of two Anglo-Scandinavian settlements, known as Tanshelf and Kirkby. In Yorkshire, place-name locations often contain the distinctive Danish '-by' i.e. Kirkby. And even today, the major streets in Pontefract are designated by the Danish word 'gate' e.g. Bailygate.

Tanshelf and Kirkby

The Anglo-Scandinavian township of Tanshelf recorded variously as Tateshale, Tateshalla, Tateshalle or Tatessella in the 1086 Domesday Book existed in the region that is today occupied by the town of Pontefract. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes its first reference to Tanshelf in the year 947 when King Eadred of England met with the ruling council of Northumbria to accept its submission. King Eadred did not enjoy Northumbria's support for long, and a year later the kingdom voted Eric Bloodaxe King of York.[9]

When the Domesday Book was commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1086 Tanshelf was still a sizeable settlement for the period. The town had a priest, 60 petty burgesses, 16 cottagers, 16 villagers and 8 smallholders, amounting to a total of 101 people. But the actual size of the population might be as much as four or five times larger than this as the people listed are landholders, and therefore the Doomsday Book does not take their families into account. Tanshelf also had a church, a fishery and three mills. Archaeologists have discovered the remains of the church on The Booths in Pontefract, off North Baileygate, below the castle. The oldest grave dates from around 690. The church is likely to be at Tanshelf and may have been similar to the church at Ledsham. The area which is now the town market place was the original meeting place of the Osgoldcross wapentake.[10] In the Anglo-Saxon period a part of the modern township of Pontefract was known by the Anglo-Scandinavian name of Kirkby.

Medieval

Norman conquest

After the Norman conquest in 1066 almost all of Yorkshire came under the ownership of followers of William the Conqueror,[11] one of whom was Ilbert de Lacy who became the owner of Tateshale (Tanshelf) where he began to build a castle.[11] Pontefract Castle began as a wooden motte and bailey castle, built before 1086 and later rebuilt in stone. The de Lacys lived in the castle for more than two centuries[12] and were holders of the castle and the Honour of Pontefract from 1067[13] until the death of Alice de Lacy in 1348.[14]

King Richard II was murdered at the castle in 1400.[15][16] Little is known of the precise nature of his demise; in particular Shakespeare may have "adjusted" the facts for his own purposes.[17] There are at least three theories which attempt to explain his death:[18] He was starved to death by his keepers, he starved himself to death or he was murdered by Sir Piers (Peter) Exton on 14 February 1399 or 1400.[19]

Robin Hood and the outlaw's connection to Pontefract

The town of Pontefract and the village of Wentbridge are of central importance to the legend of Robin Hood, as it was told in the Middle Ages.[20] The Fifteenth century Robin Hood ballads place the outlaw's activities in the forest of Barnsdale, the southern edge of which bordered modern Wakefield.[21] The earliest surviving manuscript of a Robin Hood ballad, "Robin Hood and the Potter" makes reference to Wentbridge: "'Y mete hem bot at Went breg,' s(e)yde Lytyll John" ('I met him but at Wentbridge', said Little John). Likewise, the Fifteenth Century ballad "A Gest of Robyn Hode", appears to make a cryptic reference to the village by depicting a friendly knight explaining to Robin that he ‘went at a brydge’ where there was 'a wraste-lyng' (wrestling).[22] Significantly, the Gest of Robyn Hode makes a very specific reference to a location within Wentbridge known as 'the Saylis' and 'the Sayles', as in a four line stanza the outlaw chief instructs his Merry Men to,

"Walk up to the Saylis

And so to Watling Street

And wait after some uncouth guest

Upon Chance you may them meet"

The 19th-century antiquarian Joseph Hunter identified the site of the Saylis: a small tenancy, of one-tenth of a knight's fee (i.e. a knight's annual income), located on high ground 500 yards (457.2 metres) to the east of the village of Wentbridge in the manor of Pontefract.[23] The Saylis is recorded as having contributed towards the aid that was granted to King Edward III in 1346-47 for the knighting of his son, the Black Prince.[24] The late, great historians Richard Barrie Dobson and John Taylor indicated that this location provides a very specific clue to Robin Hood's Pontefract heritage, noting that such evidence of continuity makes it virtually certain that the Saylis or Sayles, which was so well known to the Robin Hood of the "Gest" survived into modern times as the 'Sayles Plantation' near Wentbridge.[25] To commemorate this, English Heritage has sited a Blue Plaque on the bridge that stands in the heart of the village, above the River Went, lending weight to Pontefract's claims to be the true home of Robin Hood.[26]

Wentbridge is a small village in the City of Wakefield district of West Yorkshire, England. It lies around 3 miles (5 km) southeast of its nearest town of size, Pontefract, close to the A1 road. During the Middle Ages the village of Wentbridge was itself sometimes referred to by the name of Barnsdale because it was the main settlement in the Forest of Barnsdale. The county boundary follows the A1 from the River Went to Barnsdale Bar, which is the southernmost point of North Yorkshire. Close by to the southwest is the Roman Ridge, a Roman road, known in the Middle Ages as Watling Street, closely follows the course of the modern-day A639. It was at one time, prior to modern construction works being completed, possible to look down from the Saylis upon Watling Street as it snaked through the village of Wentbridge and it is upon this stretch of highway that Robin Hood and his Merry Men are believed to have committed their famous heists. Earlier historians have usually assumed that this district was heavily wooded. However, aerial photography and excavation have shown that the region has always been a largely pastoral landscape dotted with occasional settlements.[27] In close proximity to the village of Wentbridge there are, or were, some notable landmarks which relate to Robin Hood. The earliest-known Robin Hood place-name reference - in Yorkshire or anywhere else - occurs in a deed of 1322 from the two cartularies of Monk Bretton Priory, near the town of Barnsley.[28] The cartulary deed refers in Latin to a landmark named 'the Stone of Robert Hode' (Robin Hood's Stone), which was located in the Barnsdale area. According to J. W. Walker this was on the eastern side of the Great North Road, a mile south of Barnsdale Bar.[29] On the opposite side of the road once stood Robin Hood's Well, which has since been relocated six miles north-west of Doncaster, on the south-bound side of the Great North Road.[30]

Further evidence of Robin Hood's Wakefield connections comes by way of Michael Drayton's Poly-Olbion Song 28 (67–70), composed in 1622. The poem strengthens Robin Hood's connections to Pontefract because it speaks of the outlaw's death and clearly states that the outlaw died at 'Kirkby'. Kirkby was an Anglo-Saxon settlement upon which the modern town Pontefract stands.[31] In 2014, the historian Dr S. A. La' Chance published a thesis that detailed how a notorious medieval outlaw named Swein-Son-Of-Sicga, and styled by contemporaries as 'The Prince of Thieves' inhabited the forested areas of Barnsdale, on the outskirts of Pontefract, and made a living by robbing, amongst others Abbot Benedict of Selby. Professor J. Green indicates that Hugh Fitz Baldric, the late eleventh century Sheriff of Nottingham and Yorkshire, held responsibility for bringing Swein-Son-Of-Sicga to justice.[32] Acknowledging this, La' Chance suggested that the Robin Hood legend is loosely based upon the deeds of Swein-Son-Of-Sicga. La' Chance closed his thesis by suggesting that, in all likelihood, the outlaw drew his final breath at Saint Nicholas's hospital, Kirkby (modern day Pontefract), which would account for the reference to Robin Hood's death in the Poly-Olbion.[33]

Early modern history

Tudor

In Elizabethan times the castle, and Pontefract itself, was referred to as "Pomfret".[15] William Shakespeare's play Richard III mentions the castle:

Pomfret, Pomfret! O thou bloody prison,

Fatal and ominous to noble peers!

Within the guilty closure of thy walls

Richard the second here was hack'd to death;

And, for more slander to thy dismal seat,

We give thee up our guiltless blood to drink.[15]

Pomfret is referred to in Shakespeare's Richard II also.[34]

My lord, the mind of Bolingbroke is changed:

You must to Pomfret, not unto the Tower.

And, madam, there is order ta'en for you;

With all swift speed you must away to France

Stuart history

Civil war

Pontefract suffered throughout the English Civil War. In 1648–49 the castle was laid under siege by Oliver Cromwell, who said it was "... one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom."[15] Three sieges by the Parliamentarians left the town "impoverished and depopulated".[35] In March 1649, after the third siege, Pontefract inhabitants, fearing a fourth, petitioned Parliament for the castle to be slighted.[35] In their view, the castle was a magnet for trouble,[35] and in April 1649 demolition began.[35] The ruins of the castle remain and are publicly accessible.

Pontefract Priory history

Pontefract was the site of Pontefract Priory, a Cluniac priory founded in 1090 by Robert de Lacy dedicated to St John the Evangelist. The priory was dissolved by royal authority in 1539. The abbey maintained the Chartularies of St John, a collection of historic documents later discovered among family papers by Thomas Levett, the High Sheriff of Rutland and a native of Yorkshire, who later gave them to Roger Dodsworth, an antiquary.[36] They were later published by the Yorkshire Archaeological Society.[37]

Pontefract today

_geograph.jpg)

Pontefract has been a market town since the Middle Ages; market days are Wednesday and Saturday, with a smaller market on Fridays. The covered market is open all week, except Thursday afternoons and Sundays. Thursday afternoon is half-day closing in the town. The town is called 'Ponte'/'Ponty' by its citizens and sometimes jokingly referred to as Ponte Carlo, in reference to Monte Carlo. This theme is continued in the name of bars in the Xscape complex, Glasshoughton between Pontefract and Castleford, referred to locally as 'Cas Vegas'. Numerous pubs can be found in the town centre in particular, for example Beastfair Vaults, the Liquorice Bush, the Red Lion, the Malt Shovel and the Blackmoor Head. A Wetherspoon public house opened on Horsefair in 2010. It is said by some that Pontefract once held a record for being the town with the highest number of pubs per square mile in the UK [38][39], but this is likely an urban legend, and the title is currently held by another town [40]

Pontefract's deep, sandy soil makes it one of the few British places in which liquorice can successfully be grown. The town has a liquorice-sweet industry; and the famous Pontefract cakes are produced, though the liquorice plant itself is no longer grown there. The town's two liquorice factories are owned by Haribo (formerly known as Dunhills) and Tangerine Confectionery (formerly part of the Cadbury's Group as Monkhill Confectionery, and before that Wilkinson's), respectively. A Liquorice Festival is held annually. Poet laureate Sir John Betjeman wrote a poem entitled "The Licorice Fields at Pontefract". In 2012 local farmer Robert Copley announced that he would be re-introducing a liquorice crop to Pontefract.[41][42]

Close by is the site of the former coal-fired power station at Ferrybridge, although the local coal mines largely closed in the 1990s, contributing to high unemployment in the local area. The final colliery, Prince of Wales Colliery, closed in August 2002.[43]

There are a number of supermarkets in Pontefract which include a Tesco and Morrisons which are located opposite each other, and an Asda, which was originally a Kwik Save store, a short distance outside the town centre. The secondary schools in the town are Carleton Community High School in Carleton, and the King's School on Mill Hill Lane, both for pupils aged 11–16. A sixth-form college, NEW College, Pontefract, is located on Park Lane.

The old Pontefract General Infirmary on Southgate (pictured) was a general hospital; it is the place at which serial killer Harold Shipman began to murder his elderly patients. Beneath this building is an old hermitage, open to the public on certain days. Pontefract Museum, from which the hermitage schedule can be obtained, is in the town centre, housed in the former Carnegie library. A new hospital was built on Friarwood and opened in 2010 with the new name of Pontefract Hospital and there is now a modern library building.

Near to the hospital is Friarwood Valley Gardens, a rose garden, a sensory garden, a pinhole camera (formerly an aviary and earlier a Georgian gambling den), and an avenue of cherry trees. Friends of Friarwood Valley Gardens now work to improve it.

Pontefract has three railway stations: Pontefract Baghill, on the Dearne Valley Line, which connects York and Sheffield; and Pontefract Monkhill and Pontefract Tanshelf, which connects with Leeds and Wakefield. There are also rail services from Bradford to London that stop at Pontefract Monkhill.

The local police force is West Yorkshire Police, with the town's neighbourhood policing team being situated at the new fire station on Stumpcross Lane. The original police station situated in Sessions House yard is due for closure since the new divisional headquarters for the Wakefield District opened in Normanton and the neighbouring magistrates' court has moved over to Leeds following the closure of the Wakefield and Pontefract courts..

Fire cover is provided by West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue with one pump (sometimes two) based at Pontefract Fire Station. Formerly located on Stuart Road in the town centre, the station has now moved to a new site at Stumpcross Lane, by the A645 road at the town's eastern edge. The new fire station also provides cover for Knottingley, that town's fire station having been closed as part of the merging of fire cover for Pontefract and Knottingley.

The Territorial Army, Army Cadets and Air Training Corps all have a presence within the town and are based at the historic Pontefract Barracks building on Wakefield Road. It now houses a Rifles Regiment Recruitment team.

A house on Chequerfield Estate is said to be haunted by a poltergeist, nicknamed The Black Monk of Pontefract.[44]

Media, arts and entertainment

The local newspaper is the Pontefract and Castleford Express. Pontefract is known for its 'down-to-earth' nightlife.[45] Venues include The Red Lion, the Green Dragon, the Tap and Barrel, The Broken Bridge (Wetherspoons), the Malt Shovel, and the Ponty Tavern (formally The Blackmoor Head) or Blacky in local terms. In August 2012 one of Pontefract's oldest but most prestige nightclubs, Kiko's, re-opened its doors to the public after being closed since 2007, then closed again in 2013 due to the building being too far away from the town & other nightlife spots. Kiko's once hosted many notable performances back in the 1970s and 80s from notable bands such as The Bay City Rollers. As of Early 2020 the building is now vacant & severely damaged inside awaiting revival, venue change or demolition.

Novelist Jack Vance, in the "Demon Princes" cycle has named the capital of Aloysius, the main planet in the Vega system, after Pontefract. The hero of the series, Kirth Gersen, has his residence there.

Ridings FM is the town's local commercial radio station, Launched in October 1999, Ridings FM can be heard across Pontefract on 106.8 FM. The station serves the wider Wakefield District. The station has a close relationship with the community and is actively involved in local charities' fundraising efforts.

Pontefract, made local and national newspapers in April 2020, with a range of Art which lay tribute to the key workers and NHS during the coronavirus outbreak. The art was painted by a local mural artist, Rachel List.[46]

Governance

For local government purposes the town lies in the City of Wakefield, coming under the governance of Wakefield Council. For this purpose it is divided into two electoral wards, Pontefract North and Pontefract South. Pontefract South is currently represented by three Labour councillors with North ward represented by three Labour councillors [as of September 2015].[47] South ward is a marginal ward, containing relatively affluent suburbs of Pontefract and outlying villages such as Darrington, combined with less wealthy areas such as Chequerfield, whilst North Ward includes parts of Monkhill, Ladybalk, Nevison and Myson Chair.

From 1978 to 1997 the local ex-miner and former local NUM branch leader Geoff Lofthouse (18 December 1925 – 1 November 2012) was MP for the former constituency of Pontefract and Castleford. During this time he rose to the position of Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons. When the general election of 1997 was called he stood down to allow Yvette Cooper to be selected as the Labour Party candidate for that election. He was made a peer on 11 June 1997.

Yvette Cooper MP, was elected MP for the Pontefract and Castleford constituency at the 1997 general election. Cooper held a number of positions in the Labour governments up to 2010, followed by Shadow Cabinet roles (most notably Shadow Home Secretary) after the election of that year, but returned to the back benches following the Labour leadership election of 2015. Pontefract and Castleford was merged with the Normanton constituency in a boundary change before the 2010 general election.

In her maiden speech to the House of Commons, Cooper said:

It is true that my constituency is plagued by unemployment, but I represent hard-working people who are proud of their strong communities and who have fought hard across generations to defend them. They are proud of their socialist traditions, and have fought for a better future for their children and their grandchildren. In the Middle Ages, that early egalitarian, the real Robin Hood, lived, so we maintain, in the Vale of Wentbridge to the south of Pontefract. It was a great base from which to hassle the travelling fat cats on the Great North Road.

The seat, which has a history of mining and industry, has consistently returned Labour MPs at general elections. Yvette Cooper polled 59.5% of the vote in the 2017 general election. Support appears to have fallen with the majority falling to 48.1% of the vote in the 2019 general election.

Sports

The town is home to many sports including cricket, football and squash. Prominent squash players Lee Beachill and James Willstrop both train at Pontefract Squash Centre. Notable institutions are horse racing at Pontefract Racecourse and Featherstone Rovers, the area's professional rugby league club.

Pontefract Racecourse is the longest continuous horse racing circuit in Europe at 2 miles 125 yards (3,333 m; 16.57 furlongs).[48] It stages flat racing between the end of March and the end of October. Pontefract swimming pool is on Stuart Road.

Pontefract has its own non-league football club, Pontefract Collieries F.C., which was founded in 1958 and plays adjacent to the former Prince of Wales Colliery off Beechnut Lane. The team, known locally as "Ponte Colls" play in the Northern Premier League Division One North West (correct as of the start of the 2019/20 season). Pontefract is also home to the Pontefract Knights rugby league football club.

Pontefract RUFC is based at Moor Lane Carleton. It runs three senior sides as well as a number of junior and girls teams. Rugby Union has been played in the town since the 19th century when Pontefract won the Yorkshire Cup.

Pontefract used to boast two cricket clubs, Lakeside CC (based in Pontefract Park) and Pontefract CC (adjacent to Pontefract Collieries FC), but by 2002 neither of these clubs were still in existence, leaving the town without its own club despite giving its name to the Pontefract and District Cricket League. Nowadays cricketers must travel to clubs in neighbouring towns and villages, with the closest being Hundhill Hall Cricket Club based in nearby East Hardwick.

Transport

Pontefract lies in close proximity to the A1 and the M62. Bus transport is provided by Arriva Yorkshire, the main hub in the town for this being Pontefract bus station. The town has direct rail connections with Leeds, Wakefield, Goole, Castleford, York and Sheffield from the town's three railway stations; Pontefract Monkhill, Pontefract Tanshelf and Pontefract Baghill. The closest airports are Leeds Bradford and Doncaster Sheffield

Notable people

- Thurstan of Bayeux, (c. 1071–1140), archbishop, died at Pontefract.

- Richard de Pontefract (?–1320?), Dominican friar

- John Ramsden (1594–1646), High Sheriff of Yorkshire, MP for Pontefract in the Short Parliament, and Royalist soldier

- John Jackson (1595?–1637), MP for Pontefract during the Happy Parliament

- Francis Drake (1696–1771), antiquary and surgeon

- Robert Monckton, (1726–1782), MP for Pontefract and British army general

- John Smyth (1748–1811), MP for Pontefract

- Jesse Hartley (1780–1860), civil engineer and Superintendent of the Concerns of the Dock Estate, Liverpool; built the Albert Dock and many other parts of Liverpool Docks

- Charles Coleman (1807–1874), English painter

- Isaac Cole (1886–1940), rugby union and league player who represented England

- Edward Upward (1903–2009), novelist, lived in Pontefract from 2004 until his death in 2009

- Barbara Castle (1910–2002), Labour Party politician

- John Poulson (1910–1993), architectural designer and businessman

- Don Robinson (1932–2017), 1954 Rugby League World Cup winning rugby league footballer who represented Great Britain, Wakefield Trinity, Leeds, and Doncaster

- Mal Kirk (1936–1987), wrestler

- Margaret Drabble (1939–), novelist, was evacuated to Pontefract during WW2[49]

- Harvey Proctor (1947–), Conservative Member of Parliament[50]

- Mick Jackson (1947–), musician, writer of "Blame It on the Boogie"[51]

- Kevin Moreton (1959 ), actor known for Coronation Street

- Jane Collins (1962– ), politician, UKIP, Brexit Party MEP Yorkshire (2014–2019)

- Paul Crichton (1968– ), former footballer who currently serves as goalkeeping coach for Huddersfield Town

- Helen Baxendale (1970–), actress known for Cold Feet, Friends and Cuckoo

- Paul Newlove (1971– ), English rugby league footballer who played in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s

- Dave Smith (1971– ), professional darts player from Knottingley, Wakefield, West Yorkshire

- Chris Silverwood (1975– ), cricketer who represented Yorkshire and current coach of the England Men's Cricket team

- Jamie Davis (1981– ), actor, best known for his roles in Footballers' Wives, Hex and currently in Casualty as Max Walker

- Rob Burrow (1982– ), rugby league footballer with Leeds; he has represented both England and Great Britain

- Toby Kebbell (1982– ) actor known for "Black Mirror", "RocknRolla", "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes", "Warcraft", "Kong: Skull Island"

- Jamie McCombe, (1983– ), footballer who currently plays for Doncaster Rovers

- Paul Green (1983– ), footballer who plays for Oldham in the English Football League

- Tim Bresnan (1985– ), cricketer who has represented Yorkshire and England

- Ben Parker (1987– ), former footballer who played for Leeds United and represented England U19

- Oliver Hindle (1988– ), artist and musician, best known for his band project Superpowerless

- Max Litchfield (1995– ), swimmer, silver medallist in the 400m medley at the European Long Course Championships

- Jake Johnson (2002), British gymnast

- Robin Hood

Location grid

Notes

- "Pontefract South Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- "Pontefract North Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Padgett 170

- Eric Houlder, Ancient Roots North: When Pontefract Stood on the Great North Road, (Pontefract: Pontefract Groups Together, 2012) p.7.

- Orderic Vitalis, Ecclesiastical History of England, 2:27.

- Ayto & Crofton

- Frank Barlow, William I and the Norman Conquest (London: The English Universities Press, 1965) p.95. David Crouch, The Normans: The History of a Dynasty (London: Hambledon and London, 2002) p.105

- "Ferrybridge Henge extension discovered in West Yorkshire". Culture24. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- Towns in Anglo-Saxon West Yorkshire Archived 13 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Settlements in Anglo-Saxon West Yorkshire. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- Hey

- Fletcher 16–17

- Padgett 54

- Padgett 55

- Padgett 85

- "Yorkshire's Castles: Pontefract Castle"; H2G2.com, Not Panicking Ltd.

- Padgett 106

- Holmes 373

- Holmes 373, 374

- Holmes 374

- Bellamy, John, Robin Hood: An Historical Enquiry (London: Croom Helm, 1985). Bradbury, Jim, Robin Hood (Stroud: Amberley Publishing: 2010). Dobson, R.B., "The Genesis of a Popular Hero" in Robin Hood in Popular Culture: Violence, Transgression and Justice, ed. by Thomas Hahn (Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 2000) pp. 61–77. Keen, Maurice, The Outlaws of Medieval Legend, 2nd edn (London and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul; Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1977). Maddicot, J.R., Simon De Montfort (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- Lewis, Brian, Robin Hood: A Yorkshire Man. Dr Eric Houlder, PontArch Archaeological Society.

- The Gest of Robyn Hode, Stanza 135 p.88

- Joseph Hunter, "The Great Hero of the Ancient Minstrelsy of England", Critical and Historical Tracts 4 (1852 pp. 15-16).

- Hunter, pp. 15-16)

- Dobson, R. B. and John Taylor, Rymes of Robyn Hode: An Introduction to the English Outlaw, 3rd edition (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1997) p.22

- English Heritage Blue Plaque, Awarded to Wentbridge, Pontefract (photo to follow soon)

- Eric Houlder, Ancient Roots North: When Pontefract Stood on the Great North Road, (Pontefract: Pontefract Groups Together, 2012) p.7.

- In 1924 the antiquary J. W. Walker redated the deed to 1422 (with apparently excellent justification), claiming an alleged scribal error, and this redating has been widely accepted ever since. ( See ref 4 below.) In both cartularies the actual year written on the 'Robin Hood's Stone' deed is 1322. The older of the two surviving Monk Bretton cartularies is in the British Library. In this the full date of the deed is given, in Latin words and numerals. These translate directly as 'the Sixth of June, the Lord's Day, in the Feast of the Holy Trinity, One-Thousand 300 Twenty-Two' (ie Trinity Sunday, 6 June 1322). This is a perfectly correct date, both in the Church Calendar and in the civil Julian Calendar, which was used in the British Isles until the middle of the 18th century. In 1322 the Sixth of June fell on a Sunday, and Sunday the Sixth of June was Trinity Sunday. In 1422 the Sixth of June fell on a Saturday, and Trinity Sunday was the Seventh of June. (Calendar years are not repeated at 100-year intervals in either the Julian or Gregorian calendars.) In the date itself there is no evidence of scribal error. See C. R. Cheney and Michael Jones: A Handbook of Dates for students of British history (London: Royal Historical Society 1945/new edition: Cambridge University Press 2000, reprinted 2004) pp196-199. See also Jim Lees: "The Quest for Robin Hood" (Nottingham: Temple Nostalgia Press 1987) p120.

- "Abstracts of the Chartularies of the Priory of Monkbretton", Record Series Vol. LXVI, edited by J. W. Walker (Leeds: The Yorkshire Archaeological Society, 1924) pp105-106.

- Dobson and Taylor, p. 22

- David Hepworth, 'A Grave Tale', in Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval, ed. by Helen Phillips (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005) pp.91–112 (p.94.)

- Green, Judith A., English Sheriffs to 1154, Public Records Handbook No. 24 (London: HMSO, 1990), pp.67 & 89

- La' Chance, S. A., The Origins and Development of the Legend of Robin Hood, University of Leeds Press, The School of History, Russel Group Publishing, 2014

- "Richard II: Entire Play". shakespeare.mit.edu. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Padgett 166–169

- Madden, Frederic; Bandinel, Bulkeley (1 May 1835). Collectanea Topographica Et Genealogica. J. B. Nichols and son. p. 103. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Internet Archive.

pontefract levet.

- Early Yorkshire Charters: being a collection of documents anterior to the thirteenth century made from the public records, monastic chartularies, Roger Dodsworth's manuscripts and other available sources; edited by William Farrer. 3 vols. Edinburgh: Printed for the editor by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co., 1914–16

- Wollerton, Alison. "Pontefract". Pontefract Heritage Group. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

It has been said that Pontefract once held a world record for having the highest number of pubs per square mile.

- Krasaukas, Vincent. "The Partynice Guide to Pontefract". Partynice Magazine. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

it is believed that the town now has the highest concentration of pubs in the whole of the UK.

- "Britain's Pub Capitals". Liberty Games. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Rebecca Smithers (30 July 2012). "Liquorice to grow again in Pontefract". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- "The Home of Liquorice". Farmer Copleys. 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Wainwright, Martin (31 August 2002). "Britain's oldest mine closes". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Wilson, Colin (8 November 2010). Poltergeist: A Classic Study in Destructive Hauntings. Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 67, 152. ISBN 978-0-7387-2237-5.

- "Pontefract hotels".

- Frame, Nick; Hale, Olivia (9 April 2020). "'I never expected this'-Pontefract Artist's surprise as NHS tributes are shared across the world". Pontefract and Castleford Express. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Your Councillors by Ward". Wakefield Council. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- "Course Details – Pontefract Racecourse". Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- "My Yorkshire: Margaret Drabble". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Proctor, K. Harvey (29 March 2016). Credible and True: The Political and Personal Memoir of K. Harvey Proctor. Biteback Publishing – via Google Books.

- "PressReader.com – Your favorite newspapers and magazines". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

Sources

- Ayto, John and Crofton, Ian, Brewer's Britain & Ireland, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Fletcher, J. S. (1917), Memorials of a Yorkshire Parish (facsimile), Old Hall Press, Leeds 1993

- Hey, David, Medieval South Yorkshire

- Holmes, Richard (editor) (1887), The Sieges of Pontefract Castle (facsimile reprint), Old Hall Press, Leeds 1985 ISBN 0 946534 02 0

- Mills A. D., Oxford Dictionary of British Place-Names, Oxford University Press.

- Padgett, Lorenzo (1905), Chronicles of Old Pontefract (facsimile), Old Hall Press, Leeds 1993

.jpg)