St Asaph

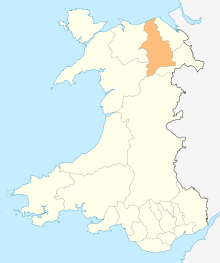

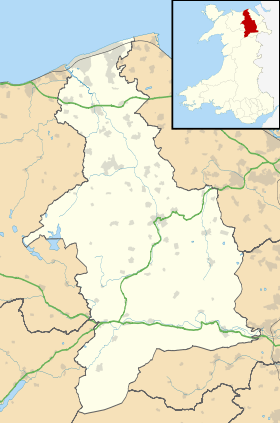

St Asaph (/ˈæsəf/;[1] Welsh: Llanelwy [ɬanˈɛlʊɨ̯]) is a city[2] and community on the River Elwy in Denbighshire, Wales. In the 2011 Census it had a population of 3,355[3] making it the second-smallest city in Britain in terms of population and urban area. It is in the historic county of Flintshire.

St Asaph

| |

|---|---|

St. Asaph Cathedral | |

St Asaph Location within Denbighshire | |

| Population | 3,355 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SJ035743 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ST. ASAPH |

| Postcode district | LL17 |

| Dialling code | 01745 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament |

|

The city of St Asaph is surrounded by countryside and views of the Vale of Clwyd. It is situated close to a number of busy coastal towns such as Rhyl, Prestatyn, Abergele, Colwyn Bay and Llandudno. The historic castles of Denbigh and Rhuddlan are also nearby.

History

The earliest inhabitants of the vale of Elwy lived at the nearby Paleolithic site of Pontnewydd (Bontnewydd), which was excavated from 1978 by a team from the University of Wales, led by Stephen Aldhouse Green. Teeth and part of a jawbone excavated in 1981 were dated to 225,000 years ago. This site is the most north-western site in Eurasia for remains of early hominids and is considered of international importance. Based on the morphology and age of the teeth, particularly the evidence of taurodontism, the teeth are believed to belong to a group of Neanderthals who hunted game in the vale of Elwy in an interglacial period.

Later some historians postulate that the Roman fort of Varae sat on the site of the cathedral. However, the city is believed to have developed around a 6th-century Celtic monastery founded by Saint Kentigern, and is now home to the small 14th century St Asaph Cathedral. This is dedicated to Saint Asaph (also spelt in Welsh as Asaff), its second bishop.

The cathedral has had a chequered history. In the 13th century, the troops of Edward I of England burnt the cathedral almost to the ground, and in 1402 Owain Glyndŵr's troops went on the rampage, causing severe damage to the furnishings and fittings. Two hundred and fifty years later, during the Commonwealth, the building was used to house farm animals: pigs, cattle and horses.[4]

The Laws in Wales Act 1535 placed St Asaph in Denbighshire. However, in 1542 St Asaph was placed in Flintshire for voting purposes. Between 1 April 1974 and 1 April 1996 it was part of non-metropolitan Clwyd.

City status

As the seat of a medieval cathedral and diocese, St Asaph was historically regarded as a city, and the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica refers to it as a city on that basis; however the UK government clarified that St Asaph was previously the only one of the twenty two ancient cathedral dioceses in England and Wales (pre-reformation) not to have been awarded city status.[5] The town applied for the status in competitions held by the British government in 2000 (for the Millennium) and 2002 (Queen's Golden Jubilee) but was unsuccessful. In 2012 it again competed for city status during the Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations. It was announced on 14 March 2012 that the application was successful, and city status was to be bestowed upon St Asaph alongside Chelmsford and Perth.[6][7] The status was formally granted by letters patent dated 1 June 2012.[8]

The award of city status is typically granted to a local authority,[9] whose administrative area is then considered to be the formal borders of the city. By this definition, the whole community area of St Asaph is considered to be the extent of the city, including its urban and rural areas. St Asaph contains the second lowest population of all the cities of the UK, and has the second smallest urban area of 0.5 sq mi (1.3 km2), both measures behind St Davids which has 1,841 residents and covers 0.23 sq mi (0.60 km2). However, with the formal city sizing defined by its community council area of 2.49 sq mi (6.4 km2), two other UK cities are smaller than St Asaph by boundary, the City of London smallest at 1.12 sq mi (2.9 km2) and Wells second with 2.11 sq mi (5.5 km2). In Wales, St Asaph is the smallest by council area, with Bangor a close second at 2.79 sq mi (7.2 km2).

Community

Despite the previous lack of official city status, the community council had referred to itself as the City of St Asaph Town Council. The local community is passionate about St Asaph's historic claim to be known as a city like its Welsh cousin St Davids, which has led to a number of local businesses using 'City' as part of their business name. The city is promoted locally as the "City of Music".

The past few decades have seen the local economy in St Asaph thrive, first with the opening of the A55 road in 1970, which took east–west traffic away from the city, and, more recently, with a business park being built, attracting investment from home and overseas.

The crowded roads in St Asaph have been a hot political issue for many years. In recent years, increasing volumes of traffic on the A525, St Asaph High Street, which links A55 with the Clwyd Valley, Denbigh and Ruthin, have led to severe congestion in the city. This congestion is having a detrimental effect on the city, and residents have repeatedly called for a bypass to take this north–south road and its traffic away from the city, but the National Assembly for Wales rejected these calls in 2004, presenting a further setback for residents campaigning on the issue.

St Asaph is now home to Ysgol Glan Clwyd, a Welsh medium secondary school that opened in Rhyl in 1956 and moved to St Asaph in 1969. It was the first Welsh medium secondary school in Wales.

Festivities

Every year the city hosts the North Wales International Music Festival, which takes place at several venues in the city and attracts musicians and music lovers from all over Wales and beyond. In past years, the main event in September at the cathedral has been covered on television by the BBC.

Other annual events in the city include the increasingly popular Woodfest Wales crafts festival in June, the Beat the Bounds charity walk in July and the Gala Day in August.

Churches

In addition to the cathedral, there are five other churches in St Asaph covering all the major Christian denominations. The Parish Church of St Asaph and St Kentigern (Church in Wales) is placed prominently at the bottom of the High Street, across the river in Lower Denbigh Road is Penniel Chapel (Welsh Methodist) and halfway up the High Street there is Llanelwy Community Church (Baptist). At the top of the city, in Chester Street is St Winifride's (Roman Catholic) and Bethlehem Chapel (Welsh Presbyterian) in Bronwylfa Square.

Governance

The City Council comprises two wards that both elect seven councillors.[11] The presiding officer and chairperson of the council is The Rt Wp The Mayor Cllr Colin Hardie.[11]

Notable people

- See Category:People from St Asaph

A number of famous people have strong links to St Asaph, having been born, raised, lived, worked or died in the city. These include:

- Richard Ian Cox, the Vancouver-based voice actor and online radio host

- Greg Davies, comedian

- The Most Rev. Dr. A. G. Edwards, Lord Bishop of St Asaph, who was elected the first Lord Archbishop of Wales in the Church in Wales

- David Harrison, jockey

- William Mathias, composer

- Chris Maxwell, footballer

- The Rev. William Morgan (later Lord Bishop of St Asaph), who translated the Bible into Welsh in 1588

- Ian Rush, footballer, Wales captain

- Carl Sargeant, Welsh politician[12]

- Lisa Scott-Lee, singer

- Sir Henry Morton Stanley, explorer and journalist

- Neil Taylor, footballer, current Aston Villa left-back, Wales international and Team GB squad member for the London 2012 Olympics

- Dic Aberdaron, who taught himself Latin at the age of 11

- Felicia Hemans (1793–1835), poet ("The boy stood on the burning deck"; her son, G. W. Hemans engineered the Vale of Clwyd railway line through St Asaph);[13]

- Becky Brewerton, golfer on the Ladies European Tour

- Steve Williams, keyboard player, founder of Power Quest and former member of DragonForce

Another well-known individual, Geoffrey of Monmouth, served as Lord Bishop of St Asaph from 1152 to 1155. However, due to war and unrest in Wales at the time, he probably never set foot in his see.

The hospital in the city (formerly the St Asaph Union Workhouse) was named H.M. Stanley Hospital in honour of Sir Henry Morton Stanley; it closed in 2012. The city's hospice was named after Saint Kentigern. The original Welsh Bible is kept on public display in the city's cathedral.

References

Notes

- St Asaph—John Wells's phonetic blog Archived 18 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 15 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012

- BBC News—St Asaph in north Wales named Diamond Jubilee city Archived 30 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 14 March 2012

- Office for National Statistics Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine 2011 census - St. Asaph C

- T. W. Pritchard St Asaph Cathedral Guidebooks

- "St Asaph: A new Diamond city for North Wales". GOV.UK. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

- "WELCOME TO ST ASAPH". www.stasaph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 May 2000.

- "Three towns win city status for Diamond Jubilee". BBC News. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- "No. 60167". The London Gazette. 11 June 2012. p. 11125.

- "Corby City Bid" (PDF). www.corby.gov.uk. Corby Borough Council.

Applications may only be made by an elected local authority – normally, in respect of the entire local authority area.

- "Cathedral to New Inn". St Asaph City Council. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Councillors". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013.

- Carl Sargeant: Profile of long-serving AM's career - BBC News

- "George Willoughby Hemans". Grace's Guide. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

Bibliography

- T.W. Pritchard St Asaph Cathedral R J L Smith Much Wenlock (1997) ISBN 1-872665-91-8

- Dr Chis Stringer Homo Brittanicus 319 pages, publisher: Allen Lane (5 October 2006) ISBN 0-7139-9795-8, ISBN 978-0-7139-9795-8

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article St Asaph. |