Daniel Inouye

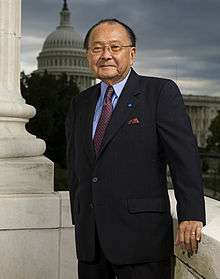

Daniel Ken Inouye (/iːˈnoʊˌeɪ/ ee-NOH-ay;[1] September 7, 1924 – December 17, 2012) served as a United States Senator from Hawaii from 1963 until his death in 2012. A member of the Democratic Party, he was President pro tempore of the United States Senate (third in the presidential line of succession) from 2010 until his death,[2] making him the highest-ranking Asian-American politician in U.S. history.[3] Inouye also chaired various Senate Committees, including those on Intelligence, Commerce and Appropriations.

Daniel Inouye | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2009 | |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office June 28, 2010 – December 17, 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Leahy |

| Chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee | |

| In office January 3, 2009 – December 17, 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Barbara Mikulski |

| Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Ted Stevens |

| Succeeded by | Jay Rockefeller |

| Chair of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee | |

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

| In office January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Mark Andrews |

| Succeeded by | John McCain |

| Secretary of the Senate Democratic Conference | |

| In office January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1989 | |

| Leader | Mike Mansfield Robert Byrd |

| Preceded by | Ted Moss |

| Succeeded by | David Pryor |

| Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee | |

| In office May 19, 1976 – January 3, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Church (Church Committee) |

| Succeeded by | Birch Bayh |

| United States senator from Hawaii | |

| In office January 3, 1963 – December 17, 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Oren Long |

| Succeeded by | Brian Schatz |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Hawaii's at-large district | |

| In office August 21, 1959 – January 3, 1963 | |

| Preceded by | John Burns (Delegate) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Daniel Ken Inouye September 7, 1924 Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, U.S. |

| Died | December 17, 2012 (aged 88) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Maggie Shinobu Awamura

( m. 1949; died 2006) |

| Children | 1 son |

| Education | University of Hawaii, Manoa (BA) George Washington University (JD) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1947 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 442nd Regimental Combat Team |

| Battles/wars | World War II (WIA) |

| Awards | |

Inouye fought in World War II as part of the 442nd Infantry Regiment. He lost his right arm to a grenade wound and received several military decorations, including the Medal of Honor (the nation's highest military award). He later earned a J.D. degree from George Washington University Law School. Returning to Hawaii, Inouye was elected to Hawaii's territorial House of Representatives in 1953, and was elected to the territorial Senate in 1957. When Hawaii achieved statehood in 1959, Inouye was elected as its first member of the U.S. House of Representatives. He was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1962. Inouye never lost an election in 58 years as an elected official, and he exercised an exceptionally large influence on Hawaii politics.

Inouye was the first Japanese American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives and the first Japanese American to serve in the U.S. Senate. Because of his seniority, Inouye became President pro tempore of the Senate following the death of Sen. Robert Byrd on June 29, 2010, making him third in the presidential line of succession after the Vice President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. At the time of his death, Inouye was the most senior sitting US senator, the second-oldest sitting US senator (seven and a half months younger than Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey), and the last sitting US senator to have served during the presidencies of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon.

Inouye was a posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Among other public structures, Honolulu International Airport has since been renamed Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in his honor.

Early life

Inouye was born on September 7, 1924, in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, the son of Hyotaro and Kame (née Imanaga) Inouye.[4] He was a Nisei Japanese American, the son of a Japanese immigrant father and a mother whose parents had migrated from Japan. He grew up in the Bingham Tract, a Chinese-American enclave in the predominantly Japanese-American community of Mōʻiliʻili in Honolulu. Inouye graduated from Honolulu's President William McKinley High School.[5]

Military service (1941–1947)

During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Inouye served as a medical volunteer.[6]

In 1943, when the US Army dropped its enlistment ban on Japanese Americans, Inouye curtailed his premedical studies at the University of Hawaii and enlisted in the Army.[6] He volunteered to be part of the segregated all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team.[7] This army formation was mostly made up of second-generation Japanese Americans from Hawaii and the mainland.[8]

Inouye was promoted to sergeant within his first year, and he was assigned as a platoon sergeant. He served in Italy in 1944 during the Rome-Arno Campaign before his regiment was transferred to the Vosges Mountains region of France, where he spent two weeks in the battle to relieve the Lost Battalion, a battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment that was surrounded by German forces. He received a battlefield commission to second lieutenant for his actions there, becoming the youngest officer in his regiment.[9] At one point while he was leading an attack, a shot struck him in the chest directly above his heart, but the bullet was stopped by the two silver dollars he happened to have stacked in his shirt pocket.[10] He continued to carry the coins throughout the war in his shirt pocket as good luck charms, until he lost them shortly before the battle in which he lost his arm.[11]

Assault on Colle Musatello

On April 21, 1945, Lt. Inouye was grievously wounded while leading an assault on a heavily defended ridge near San Terenzo in Liguria, Italy, called the Colle Musatello. The ridge served as a strongpoint of the German fortifications known as the Gothic Line, the last and most unyielding line of German defensive works in Italy. As he led his platoon in a flanking maneuver, three German machine guns opened fire from covered positions 40 yards away, pinning his men to the ground. Inouye stood up to attack and was shot in the stomach. Ignoring his wound, he proceeded to attack and destroy the first machine gun nest with hand grenades and his Thompson submachine gun. When informed of the severity of his wound, he refused treatment and rallied his men for an attack on the second machine gun position, which he successfully destroyed before collapsing from blood loss.[12]

As his squad distracted the third machine gunner, Lt. Inouye crawled toward the final bunker, coming within 10 yards. As he raised himself on his left elbow and cocked his right arm to throw his last hand grenade, a German soldier saw Inouye and fired a 30mm Schiessbecher antipersonnel rifle grenade from inside the bunker, which struck Inouye directly on his right elbow. The high explosive grenade failed to detonate, saving Lt. Inouye from instant death but amputating most of his right arm at the elbow (except for a few tendons and a flap of skin) via blunt force trauma. Despite this gruesome injury, Lt. Inouye was again saved from likely death due to the blunt, low-velocity grenade tearing the nerves in his arm unevenly and incompletely, which involuntarily squeezed the grenade tightly via a reflex arc instead of going limp and dropping it at Inouye's feet. However, this still left him crippled, in terrible pain, under fire with minimal cover and staring at a live grenade "clenched in a fist that suddenly didn't belong to me anymore."[13]

Inouye's horrified soldiers moved to his aid, but he shouted for them to keep back out of fear his severed fist would involuntarily relax and drop the grenade. As the German inside the bunker began hastily reloading his rifle with regular full metal jacket ammunition (replacing the wood-tipped rounds used to propel rifle grenades), Inouye quickly pried the live hand grenade from his useless right hand and transferred it to his left. The German soldier had just finished reloading and was aiming his rifle to finish him off when Lt. Inouye threw his grenade through the narrow firing slit, killing the German. Stumbling to his feet with the remnants of his right arm hanging grotesquely at his side and his Thompson in his off-hand, braced against his hip, Lt. Inouye continued forward, killing at least one more German before suffering his fifth and final wound of the day (in his left leg), which finally halted his one-man assault for good and sent him tumbling unconscious to the bottom of the ridge. He awoke to see the worried men of his platoon hovering over him. His only comment before being carried away was to gruffly order them back to their positions, saying "Nobody called off the war!"[14]

The remainder of Inouye's mutilated right arm was later amputated at a field hospital without proper anesthesia, as he had been given too much morphine at an aid station and it was feared any more would lower his blood pressure enough to kill him.[15]

Post-injury career

Although Inouye had lost his right arm, he remained in the military until 1947 and was honorably discharged with the rank of captain. At the time Inouye left the Army, he was a recipient of the Bronze Star Medal and the Purple Heart. Inouye was initially awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery in this action, with the award later being upgraded to the Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton (alongside 19 other Nisei servicemen who served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and were believed to have been denied proper recognition of their bravery due to their race).[16] His story, along with interviews with him about the war as a whole, were featured prominently in the 2007 Ken Burns documentary The War,[17] where he made the following statement about Medics. "To me the real heroes of war are those who seldom get medals, the Medics. Whenever a man gets injured, he very seldom calls out for his sweetheart or mother, the first thing he calls out for is a Medic, always a Medic, and whenever that word is heard, the Medic rushes over dodging bullets.......that takes guts."

While recovering at Percy Jones Army Hospital from war wounds and the amputation of his right forearm following the grenade wound, Inouye met future Republican presidential candidate Bob Dole, then a fellow patient. While at the same hospital, Inouye also met future fellow Democratic senator Philip Hart, who had been injured on D-Day. Dole mentioned to Inouye that after the war, he planned to go to Congress; Inouye beat him there by a few years. The two remained lifelong friends. In 2003, the hospital was renamed the Hart-Dole-Inouye Federal Center in honor of the three World War II veterans.[18]

Medal of Honor citation

Citation:

Second Lieutenant Daniel K. Inouye distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action on 21 April 1945, in the vicinity of San Terenzo, Italy. While attacking a defended ridge guarding an important road junction, Second Lieutenant Inouye skillfully directed his platoon through a hail of automatic weapon and small arms fire, in a swift enveloping movement that resulted in the capture of an artillery and mortar post and brought his men to within 40 yards of the hostile force. Emplaced in bunkers and rock formations, the enemy halted the advance with crossfire from three machine guns. With complete disregard for his personal safety, Second Lieutenant Inouye crawled up the treacherous slope to within five yards of the nearest machine gun and hurled two grenades, destroying the emplacement. Before the enemy could retaliate, he stood up and neutralized a second machine gun nest. Although wounded by a sniper's bullet, he continued to engage other hostile positions at close range until an exploding grenade shattered his right arm. Despite the intense pain, he refused evacuation and continued to direct his platoon until enemy resistance was broken and his men were again deployed in defensive positions. In the attack, 25 enemy soldiers were killed and eight others captured. By his gallant, aggressive tactics and by his indomitable leadership, Second Lieutenant Inouye enabled his platoon to advance through formidable resistance, and was instrumental in the capture of the ridge. Second Lieutenant Inouye's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army.[19]

Congressional career

Due to the loss of his arm, Inouye abandoned his plans to become a surgeon,[6] and returned to college to study political science under the G.I. Bill. He graduated from the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 1950 with a Bachelor of Arts in political science. He earned his J.D. degree from George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., in 1953 and was elected into the Phi Delta Phi legal fraternity.

In 1953, Daniel Inouye was elected to the Hawaii territorial House of Representatives and was immediately elected majority leader. He served two terms there, and was elected to the Hawaii territorial senate in 1957.

Midway through Inouye's first term in the territorial senate, Hawaii achieved statehood. He won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as Hawaii's first full member, and took office on August 21, 1959, the same date Hawaii became a state; he was re-elected in 1960.

United States Senate

In 1962, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, succeeding fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

He was the Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee between 1976 and 1979 and Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee between 1987 and 1995. He introduced the National Museum of the American Indian Act in 1984 which led to the inauguration of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. He was Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee between 2001 and 2003, Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee between 2007 and 2009 and Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee between 2009 and 2012.

He was reelected eight times, usually without serious difficulty. His closest race was in 1992 when state senator Rick Reed held him to 57 percent of the vote—the only time he received less than 69 percent of the vote. He delivered the keynote address at the turbulent 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago[6] and gained national attention for his service on the Senate Watergate Committee.

Inouye was also involved in the Iran-Contra investigations of the 1980s, chairing a special committee (Senate Select Committee on Secret Military Assistance to Iran and the Nicaraguan Opposition) from 1987 until 1989. During the hearings, Inouye referred to the operations that had been revealed as a "secret government" saying:

[There exists] a shadowy Government with its own Air Force, its own Navy, its own fundraising mechanism, and the ability to pursue its own ideas of the national interest, free from all checks and balances, and free from the law itself.[20]

— Daniel Inouye

Criticizing the logic of Marine Lt. Colonel Oliver North's justifications for his actions in the affair, Inouye made reference to the Nuremberg trials, provoking a heated interruption from North's attorney Brendan Sullivan, an exchange that was widely repeated in the media at the time. He was also seen as a pro-Taiwan senator and helped in forming the Taiwan Relations Act.

On May 1, 1977, Inouye stated that President Carter had telephoned him to express his objections to a sentence in the Senate Intelligence Committee's report on the Central Intelligence Agency.[21]

On November 20, 1993, Inouye voted against the North American Free Trade Agreement.[22] The trade agreement linked the United States, Canada, and Mexico into a single free trade zone and was signed into law on December 8 by President Bill Clinton.[23]

In 2009, Inouye assumed leadership of the powerful Senate Committee on Appropriations after longtime chairman Robert Byrd stepped down. Following the latter's death on June 28, 2010, Inouye was elected President pro tempore, the officer third in the presidential line of succession.

In 2010, Inouye announced his decision to run for a ninth term.[24] He easily won the Democratic primary—the real contest in this heavily Democratic state—and then trounced Republican state representative Campbell Cavasso with 74 percent of the vote.

Inouye ran for Senate majority leader several times without success.[25]

Prior to his death, Inouye announced that he planned to run for a record tenth term in 2016 when he would have been 92 years old.[26][27] He also said,

I have told my staff and I have told my family that when the time comes, when you question my sanity or question my ability to do things physically or mentally, I don't want you to hesitate, do everything to get me out of here, because I want to make certain the people of Hawaii get the best representation possible.[28]

1980s

In 1986, West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd opted to run for Senate Majority Leader, believing that his two opponents to claiming the position would be Inouye and Louisiana Senator J. Bennett Johnston. Cutting a deal with Inouye, Byrd pledged that he would step aside from the position in 1989 in the event that Inouye supported him for Majority Leader for the 100th United States Congress. Inouye accepted the offer and was given the chance to select the new Senate sergeant-at-arms. Inouye publicly did not deny this deal, though implied his backing of Byrd for Majority Leader was from both respect and friendship.[29] The same year as the deal with Byrd, Inouye was named as one of the 80 individuals to receive the Ellis Island Medal of Honor from the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation.[30]

Foreign policy

In early 1981, Inouye called for tighter restrictions on what Americans can ship overseas, citing his belief that American international stature would be harmed along with the country's foreign policy interests in the event of the shipments causing environmental damage.[31]

In March 1981, Inouye was one of 24 elected officials to issue a joint statement calling on the Reagan administration to compose a method of finding a peaceful solution that would end The Troubles in Northern Ireland.[32]

In July 1981, a Federal commission began hearings to decide on rewarding compensations to Japanese-Americans placed in internment camps during World War II, Inouye and fellow Hawaii Senator Spark M. Matsunaga delivering opening statements.[33] In November, during an appearance at the opening of a 10-day public forum at Tufts University on Japanese internment, Inouye stated his opposition to distributing reparation fees for Japanese-Americans previously incarcerated during World War II, adding that it "would be insulting even to try to do so."[34] In August 1988, Inouye attended President Reagan's signing of legislation apologizing for the internment camps and establishing a 1.25 billion trust fund to pay reparations to both those who were placed in camps and to their families.[35] In September 1989, during the Senate's debate over bestowing reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II, Inouye delivered his first public speech on the issue and noted 22,000 dollars were bestowed to each captive American in the Iran hostage crisis.[36]

Domestic policy

In April 1981, Inouye introduced a Senate joint resolution proclaiming April 19–26, 1982, as "National Nurse-Midwifery Week." Inouye stated the profession deserved such recognition because of "the unique contribution that our nation's nurse-midwives have made to the high quality of life that we possess in the United States."[37]

In March 1982, amid controversy surrounding Democrat Harrison A. Williams for taking bribes in the Abscam sting operation,[38] Inouye delivered a closing defense argument stating the possibility of the Senate looking foolish in the event the conviction was reversed on appeal. Inouye confirmed that he had received telephone calls regarding Williams critiquing his remarks during his defense of himself the previous week and questioned if the Senate was going to punish him "because his presentation was rambling, not in the tradition of Daniel Webster" and for his wife believing in him.[39] In October 1982, after President Reagan appointed two new members to the board of the Legal Services Corporation, Inouye was one of 32 Senators to sign a letter expressing grave concerns over the appointments.[40] On December 23, Inouye voted against[41] a 5 cent a gallon increase on gasoline taxes across the US imposed to aid the financing of highway repairs and mass transit. The bill passed on the last day of the 97th United States Congress.[42][43]

In March 1984, Inouye voted against a constitutional amendment authorizing periods in public school for silent prayer[44] and against President Reagan's unsuccessful proposal for a constitutional amendment permitting organized school prayer in public schools.[45][46] In August, Inouye secured the acceptance of the Senate's defense appropriations subcommittee for an amendment meant to cure mainland milk arriving at Hawaiian and Alaskan military bases sour, arguing thousands of gallons of milk coming from the mainland must be dumped due to their souring and said shipments were arriving eight days after pasteurization.[47]

In February 1989, after Oliver L. North went on trial in Federal District Court amid accusations of a dozen crimes in accordance with his role in diverting profits from the secret sale of arms to Iran to the Nicaraguan rebels and Jack Brooks questioned North's role in composing a "contingency plan in the event of an emergency that would suspend the American Constitution," Inouye replied that the inquiry touched on both a classified and sensitive matter that would only be discussed in a closed session.[30]

Gang of 14

On May 23, 2005, Inouye was a member of a bipartisan group of 14 moderate senators, known as the Gang of 14, to forge a compromise on the Democrats' use of the judicial filibuster, thus blocking the Republican leadership's attempt to implement the "nuclear option," a means of forcibly ending a filibuster.[48] Under the agreement, the Democrats would retain the power to filibuster a Bush judicial nominee only in an "extraordinary circumstance," and the three most conservative Bush appellate court nominees (Janice Rogers Brown, Priscilla Owen, and William H. Pryor, Jr.) would receive a vote by the full U.S. Senate.[49]

Electoral history

Inouye was wildly popular in his home state and never lost an election.

Family

Inouye's wife of nearly 57 years, Margaret "Maggie" Awamura Inouye, died of cancer on March 13, 2006. On May 24, 2008, he married Irene Hirano in a private ceremony in Beverly Hills, California. Hirano was president and founding chief executive officer of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, California. She resigned the position at the time of her marriage in order to be closer to her husband. According to the Honolulu Advertiser, Inouye was 24 years older than Hirano. On May 27, 2010, Hirano was elected chair of the nation's second largest non-profit organization, The Ford Foundation.[50] Inouye's son Kenny was the guitarist for the hardcore punk band Marginal Man.[51]

Honors and decorations

- Grand Cross of the Philippine Legion of Honor in 1993.[52]

- On June 21, 2000, Inouye was presented the Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton for his service during World War II.

- Also in 2000, Inouye was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun by the Emperor of Japan in recognition of his long and distinguished career in public service.[53]

- In 2006, the U.S. Navy Memorial awarded Inouye its Naval Heritage award for his support of the U.S. Navy and the military during his terms in the Senate.[54]

- Grand Cross (Bayani) of the Order of Lakandula on August 14, 2006.[55]

- In 2007, Inouye was personally inducted as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by President of France Nicolas Sarkozy[56]

- In 2008, Inouye was awarded the Israeli Chief of Staff Medal of Appreciation by Gabi Ashkenazi.

- In February 2009, a bill was introduced in the Philippine House of Representatives by Rep. Antonio Diaz seeking to confer honorary Filipino citizenship on Inouye, Senators Ted Stevens and Daniel Akaka, and Representative Bob Filner for their role in securing the passage of benefits for Filipino World War II veterans.[57]

- In June 2011, Inouye was appointed a Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers, the highest Japanese honor which may be conferred upon a foreigner who is not a head of state. Only the seventh American to be so honored, he is also the first American of Japanese descent to receive it. The conferment of the order was "to recognize his continued significant and unprecedented contributions to the enhancement of goodwill and understanding between Japan and the United States."[58]

- In 2011, Philippine president Benigno Aquino III conferred Order of Sikatuna upon Inouye. He had previously been awarded Order of Lakandula and a Philippine Republic Presidential Unit Citation.[59]

- Inouye was inducted as an honorary member of the Navajo Nation and titled "The Leader Who Has Returned With a Plan."[60]

- On August 8, 2013, Inouye was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. The citation in the press release reads as follows:

- Daniel Inouye was a lifelong public servant. As a young man, he fought in World War II with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, for which he received the Medal of Honor. He was later elected to the Hawaii Territorial House of Representatives, the United States House of Representatives, and the United States Senate. Senator Inouye was the first Japanese American to serve in Congress, representing the people of Hawaii from the moment they joined the Union.[61]

Awards and decorations

On May 27, 1947, he was honorably discharged and returned home as a Captain with a Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star Medal, 2 Purple Hearts, and 12 other medals and citations. In 2000, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.[62][63][64]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

| Combat Infantryman Badge | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st Row | Medal of Honor | Bronze Star Medal | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Row | Purple Heart (with oak leaf cluster) |

Presidential Medal of Freedom | European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (with three service stars: Rome-Arno, Northern France and Northern Apennines campaigns) |

World War II Victory Medal | ||||||||||||

| 3rd Row | Grand Cross of the Order of Lakandula (Philippines) |

Grand Cross of the Order of Sikatuna (Philippines) |

Chief Commander of the Legion of Honor (Philippines) |

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (Japan) | ||||||||||||

| 4th Row | Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan) | Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur (France) | Chief of Staff Medal of Appreciation (Israel) | Philippine Republic Presidential Unit Citation | ||||||||||||

Death

.jpg)

.jpg)

In 2012, Inouye began using a wheelchair in the Senate to preserve his knees, and received an oxygen concentrator to aid his breathing. In November 2012, he suffered a minor cut after falling in his apartment and was treated at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.[65] On December 6, he was again hospitalized at George Washington University Hospital so doctors could further regulate his oxygen intake, and was transferred to Walter Reed Medical Center on December 10. He died there of respiratory complications seven days later on December 17, 2012.[66][67] According to the senator's Congressional website, his last word was "Aloha."[68] Prior to his death, Inouye left a letter encouraging Governor Neil Abercrombie to appoint Colleen Hanabusa to succeed Inouye should he become incapacitated;[69] instead Abercrombie appointed Hawaii's Lieutenant Governor Brian Schatz.[70][71]

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid announced Inouye's death on the floor of the Senate, referring to Inouye as "certainly one of the giants of the Senate." Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell referred to Inouye as one of the finest Senators in United States history.[72] President Barack Obama referred to him as a "true American hero."[73]

Inouye's body lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda on December 20, 2012.[74] President Obama, former President Bill Clinton, Vice President Joe Biden and House Speaker John Boehner spoke at a funeral service at the Washington National Cathedral on December 21. Inouye's body was then flown to Hawaii where it lay in state at the Hawaii State Capitol on December 22. A second funeral service was held at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu the following day.[75][76][77]

Legacy

In 2007, The Citadel dedicated Inouye Hall at the Citadel/South Carolina Army National Guard Marksmanship Center to Senator Inouye, who helped make the Center possible.[78]

In May 2013, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus announced that the next Arleigh Burke-class destroyer would be named USS Daniel Inouye (DDG-118).[79] The destroyer was officially christened at Bath Iron Works on June 22, 2019.[80]

In December 2013, the Advanced Technology Solar Telescope at Haleakala Observatory on Maui was renamed the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope.[81]

Numerous federal properties at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam and around Hawai'i have been dedicated to Senator Inouye, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Daniel K. Inouye Regional Center (2013)[82], the Hawaii Air National Guard Daniel K. Inouye Fighter Squadron Operations & Aircraft Maintenance Facility (2014)[83], the Senator Daniel K. Inouye Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency building (2015)[84], the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies at Fort Derussy (2015)[85], and the Pacific Missile Range Facility Daniel K. Inouye Range and Operations Center on Kauai (2016)[86].

In 2014, Israel named the Simulator room of the Arrow anti-missile defense system in his honor, the first time that a military facility has been named after a foreign national.[87]

A Boeing C-17 Globemaster III, tail number 5147, of the 535th Airlift Squadron, was dedicated Spirit of Daniel Inouye on August 20, 2014.[88]

The Parade Field at Fort Benning was rededicated to honor Senator Inouye on September 12, 2014[89]

On April 27, 2017, Honolulu's airport was renamed Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in his honor.[90]

In 2018, Honolulu-based Matson, Inc. named its newest container ship, the largest built in the United States, the Daniel K. Inouye.[91]

The University of Hawai‘i at Hilo dedicated its pharmacy college the Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy (DKICP) on December 4, 2019.[92]

See also

- List of Asian American Medal of Honor recipients for World War II

- List of Asian Americans in the United States Congress

- List of United States Congress members who died in office

References

- As pronounced by himself in "Asian Americans Should Run for Office".

- Hulse, Carl (June 28, 2010). "Inouye Sworn In as President Pro Tem". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Raju, Manu (June 28, 2010). "Daniel Inouye now in line of presidential succession". Politico. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- "Inouye". Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- "McKinley High School Hall of Honor". Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- Associated Press (Chicago), "Keynoter Knows Sting of Bias, Poverty", St. Petersburg Times, August 27, 1968.

- Go for Broke National Education Center, "Medal of Honor Recipient 2nd Lieutenant Daniel K. Inouye" Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- "100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry". GlobalSecurity.org. May 23, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- "The War". PBS. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- Smith, Larry (2004). Beyond Glory: Medal of Honor Heroes in Their Own Words. W.W. Norton and Company. p. 47. ISBN 9780393325621.

- "Inouye Reflects on War Exploits". Associated Press. August 18, 1988.

- Victor Lipman (December 18, 2012). "Leadership Lessons From The Late Sen. Daniel Inouye". Forbes. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Yenne, Bill (2007). Rising sons: the Japanese American GIs who fought for the United States in World War II. Macmillan. p. 216. ISBN 9780312354640.

- Risjord, Norman K. (2006). Giants in their time: representative Americans from the Jazz Age to the Cold War. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 180. ISBN 9780742527850.

- "The War". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- "Medal of Honor recipients". United States Army Center of Military History. August 3, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- "Daniel Inouye". Public Broadcasting system. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- Ed O'Keefe (December 20, 2012). "Bob Dole pays respects to Daniel Inouye in Capitol Rotunda". Washington Post. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Medal of Honor Recipients - World War II (Recipients G-L)". history.army.mil.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbFphX5zb8w

- "Senator Inouye Will See Carter About Release of Report on C.I.A." New York Times. May 2, 1977.

- "Senate Roll-Call On Trade Pact". New York Times. November 21, 1993.

- "Clinton Signs Free Trade Agreement". New York Times. December 9, 1993.

- Sample, Herbert A. (February 20, 2010). "Inouye to seek another Senate term". Seattletimes.nwsource.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Daniel Inouye Dead: Hawaii Senator Dies After Fight With Respiratory Complications". Huffington Post. December 17, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- Manu Raju; John Bresnahan (April 12, 2011). "Sen. Daniel Inouye goes silent on big Hawaiian race". Politico.

- Hamilton, Chris. "Inouye has more he wants to do for (Hawaii Senator emphasizes need for Democrats to remain in control)". The Maui News. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- Mizutani, Ron (April 26, 2010). "Sen. Akaka: 'God willing, I Plan to Run Again in 2012'". KHON2. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "THE BYRD-INOUYE LEADERSHIP DEAL". Washington Post. November 4, 1987.

- "North Trial Opens After Long Delay". New York Times. February 22, 1989.

- "EXPORTS OF WASTE CAUSE CONCERN". New York Times. June 28, 1981.

- "24 POLITICIANS URGE U.S. ROLE IN ENDING ULSTER STRIFE". New York Times. March 17, 1981.

- "HEARINGS START ON INTERNMENT OF JAPANESE-AMERICANS IN '42". New York Times. July 15, 1981.

- "AROUND THE NATION; Nisei Reparations Fee Is Opposed by Inouye". New York Times. November 10, 1981.

- "President Signs Law to Redress Wartime Wrong". New York Times. August 11, 1988.

- "Senate Would Speed Reparations To Survivors of Internment Camps". New York Times. September 30, 1989.

- "REFLECTIONS: Nurse-Midwives Come of Age". Washington Post. April 21, 1982.

- Bachrach, Judy. "Facing Expulsion from the Senate He Loves, Harrison Williams Finds Some Unlikely Supporters", People (magazine), February 1, 1982. "One of them, who asks for anonymity, recalls 'going over to Pete and Nancy's house in Westfield, N.J. and having coffee together. Pete looked about 80 years old—horrible.'"

- "Almost Certain Expulsion Looms Today". Washington Post. March 11, 1982.

- "SENATORS PROTEST CHOICES BY REAGAN". New York Times.

- "The 54-33 vote by which the Senate gave final..." UPI. December 23, 1982.

- Tolchin, Martin (December 24, 1982). "FILIBUSTER CUT OFF, SENATE VOTES RISE IN GAS TAX, 54 TO 33". New York Times.

- "Senate Passes Gas-Tax Bill, Closes the 97th". Washington Post. December 24, 1982.

- "SENATE VOTE ON SCHOOL PRAYER". New York Times. March 16, 1984.

- "AMENDMENT DRIVE ON SCHOOL PRAYER LOSES SENATE VOTE". New York Times. March 21, 1984.

- "SENATE'S ROLL-CALL ON SCHOOL PRAYER". March 21, 1984.

- "Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, struck a blow for fresh..." UPI. August 3, 1984.

- "Senators compromise on filibusters - May 24, 2005". CNN.com. May 24, 2005. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- Lochhead, Carolyn (May 24, 2005). "Senate filibuster showdown averted / COMPROMISE: 14 senators craft agreement to allow vote on some judicial nominees". SFGate. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- "Irene Hirano Inouye to Chair Ford Foundation – Rafu Shimpo". Rafu.com. June 3, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "Inouye". Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- Farolan, Ramon J. (May 25, 2013). "The Fight Continues". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via PressReader.

- "Daniel Inouye, Senate". Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- "Lone Sailor Award Recipients". United States Navy Memorial. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Order of Lakandula". Gov.ph. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- "France's President Sarkozy awards US Senator Inouye with the Legion of Honour medal in Washington". Townhall. Reuters. November 6, 2007. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Leila Salaverria (February 24, 2009). "4 US solons as honorary Filipinos". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- "'Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers' for Inouye". Hawaii 24/7. June 22, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Philippines Mourns Death of Senator Inouye". Philippineembassy-usa.org. December 17, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ANDREW TAYLOR, Associated Press (December 17, 2012). "Sen. Daniel Inouye of Hawaii dead at 88". M.utsandiego.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- "President Obama Names Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients". Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. August 8, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- "Inouye military biography". Asianamerican.net. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Inouye Combat Infantryman Badge". Archived from the original on July 6, 2010.

- Starr, Kevin (2009). Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950–1963. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 438. ISBN 978-0199924301. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- "Sen. Inouye hospitalized to regulate oxygen intake | Local News – KITV Home". Kitv.com. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- Blair, Chad (December 14, 2012). "Is Hawaii Sen. Dan Inouye On The Mend? No One Will Say – Honolulu Civil Beat". Civilbeat.com. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Hawaii Sen. Daniel Inouye dies at age 88". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- "Statement on the passing of Senator Daniel K Inouye". United States Congress. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- "CNN: Inouye gave preference for successor before he died". CNN. December 18, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- Kristine Uyeno (December 26, 2012). "Critics weigh in on Schatz as Senate-appointee". KHON. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- Lane, Moe (December 26, 2012). "Neil Abercrombie ignores Daniel Inouye's dying wish, picks Brian Schatz for Hawaii Senate". Red State. Eagle Publishing, Inc. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- "Daniel Inouye dies – Kate Nocera". Politico.Com. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Statement by the President on the Passing of Senator Daniel Inouye". Whitehouse.gov. December 17, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Lying in State or in Honor". US Architect of the Capitol (AOC). Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- "Funeral services set for Sen. Inouye; viewing at U.S. Capitol followed by national then local services". Kitv.com. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- "US President pays tribute to Hawaii's Daniel Inouye". Radio New Zealand International. December 21, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- Neuman, Scott (December 21, 2012). "Sen. Daniel Inouye Remembered As Quiet Inspiration". NPR. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- "Inouye Hall to be dedicated". citadel.edu. February 2, 2007.

- Defense, This story was written by Department of. "Navy Names Next Two Destroyers". www.navy.mil.

- Sharp, David (June 22, 2019). "Widow of hero Inouye christens warship bearing his name". Navy Times. Associated Press.

- "Solar Telescope Named for Late Senator Inouye". National Solar Observatory. December 16, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- Manahane, Sila (December 19, 2013). "NOAA IRC Dedication at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii". US Navy. Naval Facilities Engineering Command Hawaii.

- "Daniel K. Inouye Fighter Squadron Operations & Aircraft Maintenance Facility". Burns McDonnell.

- Lange, Katie (November 10, 2015). "State-of-the-Art Lab Helps Identify Lost Service Members". US Pacific Command.

- Gill, Lorin Eleni (October 9, 2015). "Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies renamed for Hawaii Sen. Inouye". Pacific Business News.

- Purdy, Robert (July 29, 2016). "PMRF Range and Operations Center named for late Sen. Daniel K. Inouye". hookelenews.com.

- "Arrow facility to be named for pro-Israel senator". The Times of Israel. January 6, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Hickam C-17 dedicated in honor of late Sen. Daniel Inouye". US Air Force. 15th Wing Public Affairs Office. August 24, 2014.

- "Ft. Benning Parade Field rededicated to honor WWII Medal of Honor recipient". wtvm.com. September 12, 2014.

- Staff, Web (April 29, 2017). "Honolulu airport renamed after late Sen. Daniel Inouye". khon2.com. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "New Matson Vessel Is Largest Containership Ever Built in US". Transport Topics. November 29, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- "UH Hilo College of Pharmacy building dedicated". University of Hawa'ii News. December 4, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daniel Inouye. |