History of Kollam

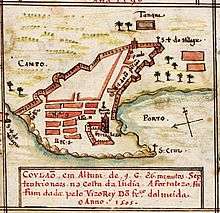

Quilon or Coulão ![]()

![]()

Since the ancient times, city of Kollam(Quilon) has played some major roles in the business, economical, cultural, religious and political history of Asia and Indian sub continent.[4] The Malayalam calendar(Kollavarsham) is also known so with the name of the city Kollam. The city is mentioned in historical citations dating back to Biblical times and the reign of King Solomon, connecting with Red Sea ports of the Arabian Sea (supported by a find of ancient Roman coins). The teak wood used in building King Solomon's throne was taken from Quilon. Merchants from Phoenicia, China, Arab countries, Dutch and the Romae used to visit and trade from Quilon in the ancient times.[5][6]

The history of the district of Kollam as an administrative unit can be traced back to 1835, when the Travancore state consisted of two revenue divisions with headquarters at Kollam and Kottayam. During the integration of Travancore and Cochin states in Kerala in 1949, Kollam was one among the three revenue divisions in the state. Later, those revenue divisions were converted as the first districts in the state.[7]

Etymology

The city name "Kollam" is believed to have been derived from the Sanskrit word Kollam (Sanskrit: कोल्लं), which means Pepper. During the ancient times, Kollam was world-famous for its trade culture, especially for the availability and export of fine quality Pepper. The sole motive of all the Portuguese, Dutch and British who have arrived the Port of Kollam that time was Pepper and other spices available at Kollam[8]

Pre-history of Kollam

Kollam is the most historic and ancient settlement in Kerala, probably in South India. Ingots excavated from Kollam city, Port, Umayanallur, Mayyanad, Sasthamcotta, Kulathupuzha and Kadakkal proved that the whole district and city were human settlements since Stone Age. Teams of archaeologists and anthropologist have conducted visits to Kollam city and Port many times for treasure hunts and researches.[9][10]

The period between 1000 BC and 500 AD is referred to as the Megalithic Culture in South India and is similar to the culture in Africa and Europe. In January 2009, the Department of Archaeology discovered a Megalithic age cist burial ground at Thazhuthala in Kollam Metropolitan Area, which had thrown lights to the past glory and ancient human settlements in Kollam area. Similar cists had been earlier discovered from the south east of Kollam. The team discovered three burial chambers, iron weapons, earthen vessels in black and red and remains of molten iron after their first major excavation in Kollam. They found a cairn circle in 1990 during their first major excavation. In August 2009, a team of archaeologists led by Dr P.Rajendran, UGC research scientist and archaeologist at the Department of History of Kerala University, had discovered Lower Paleolithic tools along with the Chinese coins and potteries from the seabed of Tangasseri in the city. This is for the first time that prehistoric cupules and Lower Paleolithic tools were discovered from below the seabed in India.[11] These tools prove that the Stone Age people lived in present Kollam area and surroundings had moved to the coastal areas during the glacial period in the Pleistocene, when the sea-level was almost 300 feet below the present sea-level.[12] Those tools are made of chert and quartzite rocks.[13]

Voyages to Quilon/Kollam

After AD.23, so many merchant travellers, explorers, missionaries, apostles and army commanders visited Quilon, as Quilon was the most important trading port in India. Pliny, Saint Thomas, Mar Sabor and Mar Proth, Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Zheng He are a few of them.

Pliny had mentioned about the port city of Quilon much accurately. By the ninth century AD., Quilon has evolved as political and trade centre of Kulsekhara dynasty of Venad Empire.

| Time | Traveller | Country from which he/she came to Quilon | Name they used to mention Quilon |

|---|---|---|---|

| A.D. 23–79 | Pliny | Roman Empire | -- |

| A.D. 522 | Cosmas Indicopleustes | Alexandria, Greece | Male[14] |

| A.D. 825 | Mar Sabor and Mar Proth | Syria | Coulão |

| A.D. 845–855 | Sulaiman al-Tajir | Siraf, Iran | Male |

| A.D. 1166 | Benjamin of Tudela | Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre(Now in Spain) | Chulam |

| A.D. 1292 | Marco Polo | Republic of Venice | Kiulan |

| A.D. 1273 | Abu'l-Fida | Hamāh, Syria | Coilon / Coilun |

| A.D. 1311–1321 | Jordanus Catalani | Sévérac-le-Château, France | Columbum |

| A.D. 1321 | Odoric of Pordenone | Holy Roman Empire | Polumbum[15] |

| A.D. 1346–1349 | Ibn Battuta | Morocco | --[16] |

| A.D. 1405–1407 A.D. 1409–1411 | Zheng He | China | --[17][18] |

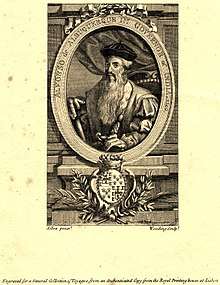

| A.D. 1503 | Afonso de Albuquerque | Kingdom of Portugal | --[19] |

| A.D. 1502–1503 | Vasco da Gama | Kingdom of Portugal | --[20] |

| A.D. 1503 | Giovanni da Empoli | Kingdom of Portugal | -- |

| A.D. 1510–1517 | Duarte Barbosa | Kingdom of Portugal | Coulam[21] |

| A.D. 1578 | Henrique Henriques | Kingdom of Portugal | --[22] |

Arrival of Saint Thomas

The arrival of Christianity in Kerala begins with the expedition of Saint Thomas, one of the 12 disciples of Jesus in AD 52. He founded Seven and a half Churches in Kerala, started from Maliankara and then Kodungallur, Kollam, Niranam, Nilackal, Kokkamangalam, Kottakkavu, Palayoor (Chattukulangara) and Thiruvithamcode Arappally (a "half church").[23][24][25]

Inception of the Port of Kollam

In 822 AD, two East Syriac bishops Mar Sabor and Mar Proth, settled in Quilon with their followers. After the beginning of Kollam Era (824 AD), Quilon became the premier city of the Malabar region ahead of Travancore and Cochin.[26] Kollam Port was founded by Mar Sabor at Thangasseri in 825 as an alternative to reopening the inland Seaport of Kore-ke-ni Kollam near Backare (Thevalakara), which was also known as Nelcynda and Tyndis to the Romans and Greeks and as Thondi to the Tamils.[26]

Migration of East Syriac Christians to Kerala started in 4th century. Their second migration is dated to the year AD 823 and that was to the city of Quilon. The tradition claims that the Christian immigrants rebuilt the city of Quilon in AD 825 from which date the Malayalam era is reckoned.[27]

Beginning of Kollam Era

Kollam Era (also known as Malayalam Era or Kollavarsham or Malayalam Calendar or Malabar Era) is a solar and sidereal Hindu calendar used in Kerala, India. The origin of the calendar has been dated as 825 CE (Pothu Varsham) at Kollam(Quilon).[28][29][30] It replaced the traditional Hindu calendar used widely else where in India and is now prominently used in Kerala. All temple events, festivals and agricultural events in the state are still decided according to the dates in the Malayalam calendar.[31]

There are many theories regarding the origin of the Malayalam calendar - the Kolla Varsham. A major theory is;

According to Herman Gundert Kolla Varsham started as part of erecting a new Shiva Temple in Kollam and because of the strictly local and religious background, the other regions did not follow this system at first. Then once the Kollam port emerged as an important trade center the other countries were also started to follow the new system of calendar. This theory backs the remarks of Ibn Battuta as well.[32][33]

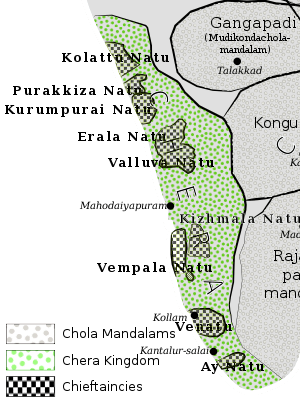

Venad - Kingdom of Quilon

The Kingdom of Quilon or Venad was one of the three prominent late medieval Hindu feudal kingdoms on the Malabar Coast in South India. The rulers of Quilon, the Venattadi Kulasekharas, traces their relations back to the Ay kingdom and the Later Cheras. The last Chera ruler, Rama Varma Kulashekhara, was the first ruler of an independent state of Quilon. In the early 14th century, King Ravi Varma established a short-lived supremacy over South India. After his death, Quilon only included most of modern-day Kollam and Thiruvananthapuram districts of Kerala and Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu. Marco Polo claimed to have visited his capital at Quilon, a centre of commerce and trade with China and the Levant. Europeans were attracted to the region during the late fifteenth century, primarily in pursuit of the then rare commodity, black pepper. Quilon was the forerunner to Travancore.[35]

In the Sangam age most of the present-day Kerala state was ruled by the Chera dynasty, Ezhimala rulers and the Ay rulers. Venad, ruled by the dynasty of the same name, was in the Ay kingdom. However, the Ays were the vassals of the Pandyas. By the 9th century, Venad became a part of the Later Chera Kingdom as the Pandya power diminished and traded with distant parts of the world. It became a semi-autonomous state within the Later Chera Kingdom. In the 11th century the region fell under the Chola empire.[36]

During the 12th century, the Venad dynasty merged the remnants of the old Ay Dynasty to them forming the Chirava Mooppan (the ruling King) and the Thrippappur Mooppan (the Crown Prince). The provincial capital of the local patriarchal dynasty was at port Kollam. The port was visited by Nestorian Christians, Chinese and Arabs. In same century, the capital of the war-torn Later Chera Kingdom was relocated to Kollam and the Kulasekhara dynasty merged with the Venad rulers. The last King of the Kulasekhara dynasty based on Mahodayapuram, Rama Varma Kulashekhara, was the first ruler of an independent Venad. The Hindu kings of Vijayanagar empire ruled Venad briefly in the 16th century.[36]

Copper Plate Inscriptions from Quilon

_plate_1.jpg)

The Tharisappalli Copper Plates (849 AD) are a copper-plate grant issued by the King of Venad (Quilon), Ayyanadikal Thiruvadikal, to the Saint Thomas Christians on the Malabar Coast in the 5th regnal year of the Chera ruler Sthanu Ravi Varma.[37] The inscription describes the gift of a plot of land to the Syrian Church at Tangasseri near Quilon (now known as Kollam), along with several rights and privileges to the Syrian Christians led by Mar Sapir Iso.[38]

The Tharisappalli copper plates are one of the important historical inscriptions of Kerala, the date of which has been accurately determined.[39] The grant was made in the presence of important officers of the state and the representatives of trade corporations or merchant guilds. It also throws light on the system of taxation that prevailed in early Venad, as several taxes such as a profession tax, sales tax and vehicle tax are mentioned. It also testifies to the enlightened policy of religious toleration followed by the rulers of ancient Kerala.

There are two sets of plates as part of this document, and both are incomplete. The first set documents the land while the second details the attached conditions. The signatories signed the document in the Hebrew, Pahlavi, and Kufic languages.[40]

The Portuguese Invasion (1502–1661)

The Portuguese were the first Europeans came to the city of Quilon. They came as traders and established a trading center at Tangasseri in Quilon during 1502. The then Queen of Quilon first invited the Portuguese to the city in 1501 for discussing about spices trade. But they refused that due to Vasco da Gama's close relations with the Raja of Cochin. Later the Queen negotiated with the Raja and he permitted to send two Portuguese ships to Quilon to buy fine quality pepper. In 1503, the Portuguese General Afonso de Albuquerque went to Quilon as per the Queen's request and collected required spices from there.[41] It is believed that the colonial era in India started with the establishment of the Portuguese trading center at Quilon in 1502.[42]

Factory in Quilon

The resumption of the pepper blockade seems to have put a crimp in Albuquerque's preparations of the return fleet, much of it having still lacked spice cargoes. Albuquerque dispatched two ships down to Quilon (Coulão, Kollam), with the factor António de Sá, to see if more could be procured there - Quilon having been better connected to Ceylon and points east, its spice supply was not as dependent on the Zamorin's sway and had often invited the Portuguese before. But soon after their departure, Albuquerque heard that the Zamorin of Calicut was preparing a Calicut fleet of some 30 ships for Quilon. Afonso de Albuquerque left Cochin and hurried down to Quilon himself.

Albuquerque arrived in Quilon, and instructed the Portuguese factor to hurry his business along, and sought out an audience with the regent-queen of Quilon.[43] They were still docked when the Calicut fleet arrived, carrying an embassy from the Zamorin with the mission to persuade (or intimidate) Quilon from abandoning the Portuguese. The regent queen of Quilon rejected the Zamorin's request, but also forbade Albuquerque from engaging in hostilities in the harbor. Albuquerque, realizing Quilon was the only spice supply he had access to, acceded to her request. Albuquerque resigned himself to negotiating a commercial treaty and establishing a permanent Portuguese factory in Quilon (the third in India), placing it under factor António de Sá, with two assistants and twenty armed men to protect the factory.[44] That settled, Albuquerque returned to Cochin on 12 January 1504 to make final preparations for his departure. Albuquerque signed a treaty of friendship with the Royal family of Quilon and established a factory there in 1503 itself. That voyage was the beginning of trade relations between Portugal and city of Quilon, which became the center of their trade in pepper. Soon, Quilon emerged as the richest town of the entire Malabar coast.[45]

End of the Portuguese era

The trade relation between Quilon and Portuguese got set back due to an insurrection happened at the Port of Quilon between the Arabs and the Portuguese. The captain of one of the Portuguese fleets saw an Arab ship is loading pepper from the port and that burst fighting between them. Aftermath, the battle started between them. 13 Portuguese men were killed including António de Sá and the St. Thomas church was burned down. To prevent further devastation, the Queen of Quilon signed a treaty with the Portuguese and as a result, they got customs tax exemption and monopoly over the spice and pepper tread with Quilon. The royal family of Quilon agreed to rebuild the destroyed church.[46][47]

The Portuguese conquered Quilon till 1661. They fought with the Arab traders and captured a huge amount of gold after killing more than 2000 Arab traders. With the arrival of the Dutch and their peace treaty signing with Quilon, the Portuguese started losing their authority on Quilon and later, Quilon officially became a Dutch protectorate.[48]

Dutch Quilon: The Dutch Invasion (1661–1795)

The Dutch started expanding their empire to India in 1602 with the commencement of Dutch East India Company. They arrived Quilon in the year 1658 and signed a peace treaty in 1659. Thus Quilon became the official protectorate of the Dutch and their officer in-charge, Rijcklof van Goens, placed a military troop in the city to protect it from probable invasions from Portuguese and the British. The West Quilon region including Tangasseri named as 'Dutch Quilon' then. But English East India Company began to follow the Dutch Method of "Triangular Trade" in early 1600s itself. The English signed a trade treaty with Portuguese and gained right to trade across the Portuguese holdings in Asia. During the mid-eighteenth century, Travancore's Raja of Marthanda Varma decided to consolidate various independent kingdoms including Quilon, Kayamkulam and Kottarakkara with Kingdom of Travancore. The plan was dismissive because of the presence of the Dutch, who fortified their base city of Quilon against such invasions. The Dutch and allies have conquered Paravur and marched to Attingal and despatched another expedition to Kottarakkara as well. But ignoring the stiff resistance, the army of Marthanda Varma attacked and defeated the Dutch at Colachel in 1741 and marched to Quilon and attacked the city. After signing the Treaty of Mannar, several territories under Quilon royal family were added to the Travancore Kingdom.[49]

Later in 1795, British gained control of Dutch Quilon and eventually became part of British Madras.[50]

References

- "History of Swathi Thirunal's Lineage". Swathithirunal.in. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (12 November 2012). Page No.710, International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. ISBN 9781136639791. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Kollam, Ashtamudi Lake - great alternatives to Kochi, Vembanad Lake". Economic Times. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Kollam on the itinerary". The Hindu. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "The legendary beauty of Kollam".

- "History of Kollam". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- "Kollam District". District Authority of Quilon. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India". 1834. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Ingots found in Kollam throws light on life of Megalithic people". Malayala Manorama - On Manorama. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Emergence of antiques triggers treasure hunt in Kollam". The Hindu. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "History under Seabed". The Hindu. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "History under Seabed". TNIE. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Megalithic age idols unearthed in Kerala". The Hindu. 12 September 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Maritime India: Trade, Religion and Polity in the Indian Ocean. Pius Malekandathil. 2010. ISBN 978-9380607016.

- René Grousset (2010). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers. p. 312. ISBN 9780813506272.

- "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Chapter 10". Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Chan 1998, 233–236.

- Zheng He's Voyages Down the Western Seas. China Intercontinental Press. 2005. pp. 22, 24, 33.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 516.

- "Vasco da Gama (c.1469–1524)". Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Boda, Sharon La (1994). Page No.710, International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. ISBN 9781884964046. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Tamil saw its first book in 1578 - The Hindu". Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- James Arampulickal (1994). The pastoral care of the Syro-Malabar Catholic migrants. Oriental Institute of Religious Studies, India Publications. p. 40.

- Orientalia christiana periodica: Commentaril de re orientali ...: Volumes 17–18. Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. 1951. p. 233.

- Adrian Hastings (15 August 2000). A World History of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8028-4875-8.

- Aiyya, V.V Nagom, State Manual p. 244

- "Before the Portuguese arrival". Malankara Orthodox Church. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218

- R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408.

- http://www.vaikhari.org/kollavarsham.html

- "Kollam - Short History". Statistical Data. kerala.gov.in. Archived from the original (Short History) on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- A. Sreedhara Menon (2007) [1967]. "CHAPTER VIII - THE KOLLAM ERA". A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books, Kottayam. pp. 104–110. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Karashima, Noboru, ed. (2014). A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780198099772.

- Keralam anjum arum noottandukalili, Prof. Ilamkulam Kunjan Pillai

- "Travancore." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. Web. 11 November 2011.

- A Survey of Kerala History - A. Sreedhara Menon. ISBN 81-264-1578-9.

- S.G. Pothan (1963) The Syrian Christians of Kerala, Bombay: Asia Publishing House.

- Cheriyan, Dr. C.V. Orthodox Christianity in India. pp. 85, 126, 127, 444–447.

- M. K. Kuriakose, History of Christianity in India: Source Materials, (Bangalore: United Theological College, 1982), pp. 10–12. Kuriakose gives a translation of the related but later copper plate grant to Iravi Kortan on pp. 14–15. For earlier translations, see S. G. Pothan, The Syrian Christians of Kerala, (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1963), pp. 102–105.

- "Kollam - Kerala Tourism". Kerala Tourism. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "The ugly and good side of conversions in South Asia". NewsIn Asia. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Barros (p.99), Correia (p.405). Curiously, Empoli (p.225), who was with the Quilon ships and witnessed the encounter, identifies the ruler as a king, not a queen. Empoli refers to the king "Nambiadora", almost certainly a variation of 'Naubeadarim' or 'Naubea Daring', names that can be frequently found in Portuguese chronicles to refer to the royal heirs in other Malabari kingdoms (e.g. Calicut, Cochin) and thus almost certainly a title. i.e. it is possible the 'king' Empoli met was just a royal prince, the queen of Quilon's heir, conducting business on her behalf.

- Barros, p.99

- Shipbuilding, Navigation and the Portuguese in Pre-modern India. United Kingdom: Routledge. 2018. ISBN 978-1138094765.

- International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Volume 5. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. 1994. ISBN 9781884964053.

- "From a Portuguese atlas, 1630". columbia.edu. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- "How the Portuguese used Hindu-Muslim wars - and Christianity - for the bloody conquest of Goa". Dailyo.in. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- M. O. Koshy (2007) [1989]. "CHAPTER 4 - The Confrontation at Colachel". The Dutch Power in Kerala, 1729-1758. Mittal Publications, New Delhi. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-81-709-9136-6. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- Boda, Sharon La (1994). Page No.712, International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. ISBN 9781884964046. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

Bibliography

- Ring, Trudy (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Volume 5. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781884964053.

- Chan, Hok-lam (1998). "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsüan-te reigns, 1399–1435". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243322.

- Lin (2007). Zheng He's Voyages Down the Western Seas. Fujian Province: China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 9787508507071.

- Yule, Henry, ed. and trans. (1863). Mirabilia descripta: the wonders of the East. London: Hakuyt Society.

- Yule, Henry (1913). "Additional notes and corrections to the translation of the Mirabilia of Friar Jordanus". Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China (Volume 3). London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 39–44.

- Henry Yule's Cathay, giving a version of the Epistles, with a commentary, &c. (Hakluyt Society, 1866) pp. 184–185, 192–196, 225-230

- Kurdian, H. (1937). "A correction to 'Mirabilia Descripta' (The Wonders of the East). By Friar Jordanus circa 1330". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 69 (3): 480–481. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00086032.

- F. Kunstmann, Die Mission in Meliapor und Tana und die Mission in Columbo in the Historisch-politische Blätter of Phillips and Görres, xxxvii. 2538, 135-152 (Munich, 1856), &c.

- Beazley, C.R. (1906). The Dawn of Modern Geography (Volume 3). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 215–235.

- Ayyar, Ramanatha (1924). Travancore Archaeological Series: Vol 1 to 7. Trivandrum: Government Press. ISBN 8186365737.

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 8126415789.

- Pothan, S G (1963). The Syrian Christians of Kerala. Mumbai: Asia Publishing House.

- Cherian, P J. Perspectives on Kerala History.

- Thundy, Zacharias. The Kerala Story: Chera times of the Kulasekharas. Northern Michigan University.

- Nair, Sivasankaran K (2005). Venadinte Parinamam. Kottayam: D C Books.