Offside (ice hockey)

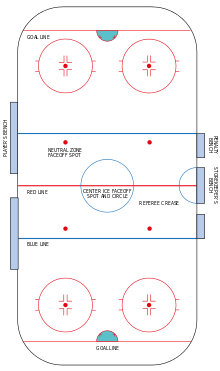

In ice hockey, a play is offside if a player on the attacking team does not control the puck and is in the offensive zone when a different attacking player causes the puck to completely cross the blue line into the offensive zone, until either the puck or all attacking players leave the offensive zone. Simply put, attacking players must not enter the attacking zone before the puck. If a player on the attacking team is in the offensive zone before the puck, they must retreat to the neutral zone

When an offside violation occurs, a linesman will stop play. To restart play, a faceoff is then held at the ice spot closest to the infraction, usually a neutral spot, or if there is a delayed penalty, at a spot in the defending zone of the defending team, which incurred the penalty. Even if the linesman erred in calling offside, the faceoff will still occur.

| No penalty | Delayed penalty | |

|---|---|---|

| Intentional Offside | defending spot of attacking team | defending spot of defending team |

| Offside | neutral spot of defending team (usually) | |

| No Offside (Error) |

Rules

Delayed offside rule

Under the delayed offside rule, an infraction occurs when a play is offside and any attacking player touches the puck or checks a player in the offensive zone. For example, under NHL's delayed offside rule, play is stopped immediately when an attacking player carries the puck into the zone while a teammate is already in the attacking zone, or when an attacking player in the neutral zone completes a pass to a teammate who is already in the attacking zone. A delayed offside occurs when a player on the attacking team is in the offensive zone before the puck and the attacking team causes the puck to enter the zone without the attacking team having possession. When a delayed offside occurs, a linesman will keep an arm up to signal it, and all attacking players must retreat back into the neutral zone without touching the puck or checking an opponent for the delayed offside to end. If an attacking player touches the puck during the delayed offside, play is stopped.

The National Hockey League (NHL) and International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) apply similar rules for determining offside. A player is judged to be offside if both of their skates completely cross the blue line dividing their offensive zone from the neutral zone before the puck completely crosses the same line. In both organizations, it is the position of a player's skates that are important. They cannot use their stick or other part of their body to remain onside. The lone caveat to this rule is that an attacking player's skates may precede the puck into the attacking zone when they are skating backwards if they are in control of the puck.[1][2] The position of the puck is used for determining offside. Offside is determined by the skate positions when the puck completely crosses the blue line. If the puck was in the attacking zone, touches the blue line, and then completely leaves the blue line back into the attacking zone, the puck is considered to have been in the attacking zone the entire time, so there is no determination of offside, and the puck did not completely cross the blue line.

If any individual player is in an offside position, their entire team is offside. A delayed offside occurs if the puck is passed or shot into the offensive zone while an attacking player is offside but has not been touched by a member of the attacking team. In most leagues, the attacking team may "tag up" by having all players exit the offensive zone. At that point the offside is waved off and they may re-enter the offensive zone in pursuit of the puck.[1] If a member of the attacking team has control of the puck while offside, a linesman will stop play and a faceoff will be held at the faceoff spot nearest the point of the infraction. Typically, this means the spot closest to the blue line if the puck is carried into the zone, or in the case of a pass, the spot closest to where the pass originated. If a linesman judges that the attacking team acted to force a deliberate stoppage in play by going offside, they can move the faceoff into that team's defensive zone.[2] If a goal is scored from a shot (at the neutral or defensive zone) that creates a delayed offside, the goal will be denied, even if the attacking team clears the offensive zone before the puck enters the goal.

Immediate offside rule

Under the immediate offside rule, an infraction occurs when a play is offside, even if the attacking team does not control the puck. Some levels of hockey use this rule and stop play instead of starting a delayed offside.

At some levels, such as younger divisions of minor hockey sanctioned by USA Hockey, the delayed offside rule is replaced by the immediate offside rule in which the linesman will stop play as soon as a play goes offside, regardless of whether or not the attacking team is in possession of the puck.[3]

Under both NHL (Rules 83.1 and 83.2) and IIHF (Rule 7) rules, there is one condition (two under NHL rules) under which an offside can be waved off even with players in the attacking zone ahead of the puck.

- A defending player has legally carried the puck out of his own zone, and then passes the puck back into his own zone only for the puck to be intercepted by an attacking player.

- (NHL only) A defending player clears the puck out of his own zone, but the puck then bounces off another defending player in neutral ice back into his own zone. (Under IIHF rules, this results in a delayed offside being signaled.)

During a faceoff, a player may be judged to be in an offside position if they are lined up within 15 feet of the centres before the puck is dropped. This may result in a faceoff violation, at which point the official dropping the puck will wave the centre out of the faceoff spot and require that another player take their place. If one team commits two violations during the same attempt to restart play, it will be assessed a minor penalty for delay of game.[4]

Offside pass

An offside pass (or two-line pass) occurs when a pass from inside a team's defending zone crosses the red line. When such a pass occurs, play is stopped and a faceoff is conducted in the defending zone of the team that committed the infraction.

There are two determining factors in an offside pass violation:

- Puck position when pass is released. Since the blue line is considered part of the zone the puck is in, if the puck is behind or in contact with the blue line when the pass is released, the pass may be an offside pass.

- Skate position of the receiver. If the receiver has skate contact with the red line at the instant the puck completely crosses it, the pass is legal regardless of where the puck actually makes contact with his stick. Both of his skates must be completely on the far side of the red line when the puck crosses the red line into the attacking zone to be governed by the aforementioned offside rule.

This offside pass rule is not observed by all leagues. For instance, it was abolished by the IIHF, and its member countries' leagues (except the NHL) in 1998. The National Hockey League adopted the version used by the top minor leagues, under the terms of their 2005 Collective Bargaining Agreement, in which the centre line is no longer used to determine a two-line pass. This was one of many rule changes intended to open up the game and improve scoring chances.

History

In the sport's earliest history, hockey was played similar to rugby, in which forward passing is not allowed. Also, hockey's offside penalty was influenced by the offside penalty from soccer. A legal pass could be made only to a teammate who is in an "onside" position behind the puck, thus forcing players to skate with the puck to move it forward.[5] In the event of an offside pass, the play was stopped and a faceoff conducted from the point of the infraction, regardless of where it occurred. The first significant relaxation of this rule occurred in 1905, when the Ontario Hockey Association began to allow defensive players to play the puck within three feet of their goal if the puck rebounded off the goaltender. In some cases, a black line was painted onto the ice surface at that three foot mark, which served as an early precursor to the modern blue lines.[6]

Forward passing within the neutral and defensive zones was first allowed in the NHL in 1927, but after a season of extremely low scoring in 1928–29, the league first allowed forward passing in all zones. The result was immediate and dramatic as the number of goals scored per game more than doubled immediately.[7] Under the NHL's new rule, there were no restrictions placed on where a player could be relative to the puck, resulting in players standing deep in their offensive zone while waiting for teammates to bring the puck forward. As a result, the NHL introduced the modern offside rule on December 16, 1929, effective six days later.[8]

The rink was divided into three zones by two blue lines as of the 1928–29 season, and the centre line did not yet exist. Teams were allowed a forward pass in any of the zones, but the puck must be carried over a blue line by a skater.[9] Frank Boucher and Cecil Duncan introduced the centre red line in the 1943–44 season, in an effort to open up the game by reducing the number of offside infractions and create excitement with quicker counter-attacks.[10] The change allowed the defending team to pass the puck to out of their own zone up to the red line, instead of being required to skate over the nearest blue line then pass the puck forward.[9]

See also

References

- "Rule 83 – Off-side". National Hockey League. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "Rule 450 – Offsides" (PDF). International Ice Hockey Federation. pp. 45–47. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "2013–17 Official Rules of Ice Hockey" (PDF). USA Hockey. p. 79. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "Rule 76 – Face-offs". National Hockey League. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- Harper, Stephen J. (2013). A Great Game: The Forgotten Leafs and the Rise of Professional Hockey. Simon & Schuster Canada. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4767-1653-4.

- Harper, Stephen J. (2013). A Great Game: The Forgotten Leafs and the Rise of Professional Hockey. Simon & Schuster Canada. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4767-1653-4.

- Pincus, Arthur (2006). The Official Illustrated NHL History. Readers Digest. p. 36. ISBN 1-57243-445-7.

- "N.H.L. moguls amend forward pass rule". Ottawa Citizen. December 17, 1929. p. 11.

- "Historical Rule Changes: 1929–30". NHL Records. National Hockey League. 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Shea, Kevin (November 19, 2011). "Spotlight – One on One with Frank Boucher". Legends of Hockey. Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 12, 2020.