Queen Maud Land

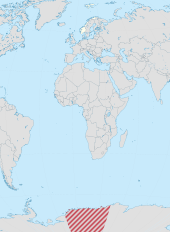

Queen Maud Land (Norwegian: Dronning Maud Land)[note 1] is a c. 2.7 million square kilometre (1.04 million sq mi)[4] region of Antarctica claimed as a dependent territory[5] by Norway. The territory lies between 20° west and 45° east, between the claimed British Antarctic Territory to the west and the similarly claimed Australian Antarctic Territory to the east. On most maps there had been an unclaimed area between Queen Maud Land's borders of 1939 and the South Pole until 12 June 2015 when Norway formally annexed that area.[6] Positioned in East Antarctica, the territory comprises about one-fifth of the total area of Antarctica. The claim is named after the Norwegian queen Maud of Wales (1869–1938).

Queen Maud Land | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Sovereign state | Norway |

| Annexed by Norway | 14 January 1939 |

| Dependency status | 21 June 1957 |

| Antarctic Treaty | 23 June 1961 |

| Expanded | 12 June 2015 |

| Sector claim | 20°W – 45°E |

| Government | Dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Harald V |

• Administered by | Ministry of Justice and Public Security |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,700,000 km2 (1,000,000 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,000 m (7,000 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 3,148 m (10,328 ft) |

| ISO 3166 code | AQ |

| Internet TLD | |

Norwegian Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen was the first person known to have set foot in the territory, in 1930. On 14 January 1939, the territory was claimed by Norway. On 23 June 1961, Queen Maud Land became part of the Antarctic Treaty System, making it a demilitarised zone. It is one of two Antarctic claims made by Norway, the other being Peter I Island. They are administrated by the Polar Affairs Department of the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security in Oslo.

Most of the territory is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, and a tall ice wall stretches throughout its coast. In some areas further within the ice sheet, mountain ranges breach through the ice, allowing for birds to breed and the growth of a limited flora. The region is divided into the Princess Martha Coast, Princess Astrid Coast, Princess Ragnhild Coast, Prince Harald Coast and Prince Olav Coast. The waters off the coast are called the King Haakon VII Sea.

There is no permanent population, although there are 12 active research stations housing a maximum of around 40 scientists, the numbers fluctuating depending on the season. Six are occupied year-round, while the remainder are seasonal summer stations. The main aerodromes for intercontinental flights, corresponding with Cape Town, South Africa, are Troll Airfield, near the Norwegian Troll research station, and a runway at the Russian Novolazarevskaya Station.[7]

Geography

Queen Maud Land extends from the boundary with Coats Land in the west to the boundary with Enderby Land in the east, and is divided into the Princess Martha Coast, Princess Astrid Coast, Princess Ragnhild Coast, Prince Harald Coast and Prince Olav Coast.[8] The territory is estimated to cover around 2,700,000 square kilometres (1,000,000 sq mi).[4] The limits of the claim, put forth in 1939, did not fix the northern and southern limits other than as "the mainland beach in Antarctica ... with the land that lies beyond this beach and the sea beyond".[9][note 2] The sea that extends off the coast between the longitudal limits of Queen Maud Land is generally called King Haakon VII Sea.[10][note 3]

There is no ice-free land at the coast; the coast consists of a 20-to-30-metre high (70 to 100 ft) wall of ice throughout almost the entire territory.[11][12][13] It is thus only possible to disembark from a ship in a few places.[13] Some 150 to 200 kilometres (90 to 120 mi) from the coast, rocky peaks pierce the ice cap, itself at a mean height of around 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) above sea level, with the highest point at Jøkulkyrkja (3,148 metres or 10,328 feet) in the Mühlig-Hofmann Mountains.[11][12] The other major mountain ranges are the Heimefront Range, Orvin Mountains, Wohlthat Mountains and Sør Rondane Mountains.[2]

Geologically, the ground of Queen Maud Land is dominated by Precambrian gneiss, formed c. 1 to 1.2 Ga, before the creation of the supercontinent Gondwana. The mountains consist mostly of crystalline and granitic rocks, formed c. 500 to 600 Ma in the Pan-African orogeny during the assembly of Gondwana.[14] In the farthest western parts of the territory, there are younger sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Research on the thickness of the ice has revealed that without the ice, the coast would be similar to those of Norway and Greenland, with deep fjords and islands.[11]

History

Early activity

Queen Maud Land was the first part of Antarctica to be sighted, on 27 January 1820 by Fabian von Bellingshausen. It was however among the last to be explored, as it required aircraft in combination with ships to undertake systematic exploration.[2] Early Norwegian research activities in Antarctica rested entirely on whaling and sealing expeditions funded by ship owners, particularly by Christen Christensen and his son Lars. The first two Norwegian expeditions were carried out by sealing ships in 1892–93 and 1893–94. While they were primarily sent for exploring, sealing, and whaling possibilities, they also performed scientific research.[15] Further Norwegian expeditions were mounted into the first decades of the 20th century.[16]

The Antarctic Plateau was claimed for Norway by Roald Amundsen as the King Haakon VII Plateau when his expedition was the first to reach the South Pole on 14 December 1911. It was mapped as a circular territory comprising the plateau around the South Pole, including all the land above latitude 85°S. However, roughly the same area had been claimed by the British as the King Edward VII Plateau, which was in conflict with the Norwegian claim. Amundsen's claim has never been officially claimed by the Norwegian government.[17][18][19]

%2C_Norwegian_aviator%2C_explorer_and_businessman_(small).jpg)

The name Queen Maud Land was initially applied in January 1930 to the land between 37°E and 49°30′E discovered by Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen and Finn Lützow-Holm during Lars Christensen's Norvegia expedition of 1929–30.[2][11] It was named after the Norwegian queen Maud of Wales, wife of the then-reigning King Haakon VII.[12] The territory was explored further during the Norvegia expedition of 1930–31.[11] During this whaling season, a total of 265 whaling ships, mostly Norwegian, worked off the coast of Queen Maud Land.[1] In the same season, Riiser-Larsen discovered the Prince Olav Coast, Princess Martha Coast and Princess Ragnhild Coast from the air. Captain H. Halvorsen of the whaler Sevilla discovered the Princess Astrid Coast independently at the same time. Six years later, during Christensen's expedition of 1936–37, Viggo Widerøe flew over and discovered the Prince Harald Coast.[2] Negotiations with the British government in 1938 resulted in the western border of Queen Maud Land being set at 20°W.[11]

Norway's claim was disputed by Germany,[20] which in 1938 dispatched the German Antarctic Expedition, led by Alfred Ritscher, to fly over as much of it as possible.[2][11] The ship Schwabenland reached the pack ice off Antarctica on 19 January 1939.[21] During the expedition, an area of about 350,000 square kilometres (140,000 sq mi) was photographed from the air by Ritscher,[22] who dropped darts inscribed with swastikas every 26 kilometres (16 mi). Germany eventually attempted to claim the territory surveyed by Ritscher under the name New Swabia,[2] but lost any claim to the land following its defeat in the Second World War.[20][note 4]

On 14 January 1939, five days prior to the German arrival, Queen Maud Land was annexed by Norway,[12] by royal decree:[11]

That part of the mainland coast in the Antarctic extending from the limits of the Falkland Islands Dependencies in the west (the boundary of Coats Land) to the limits of the Australian Antarctic Territory in the east (45° east long.), with the land lying within this coast and the environing sea, shall be brought under Norwegian sovereignty.

— Norwegian royal resolution, 14 January 1939.[23]

The primary basis for the annexation were the Norwegian explorations and the need to secure the Norwegian whaling industry's access to the region.[12][24] Scientific operations were also a basis, with Norwegian contributions to international polar science extending back to the late 19th century.[12] Norway was in addition forced to contend with competing claims made by the United Kingdom and other countries in the years prior to the Norwegian claim, including the new threat of German claims in Queen Maud Land.[24] The Norwegian claim was sometimes referred to as the "Bouvet sector", drawing from the previously annexed Bouvet Island.[20] During 1946 and 1947, vast areas of Queen Maud Land were photographed during the Richard Evelyn Byrd expedition. In 1948, Norway and the United Kingdom agreed to limit Queen Maud Land to longitudes from 20°W to 45°E, and that the Bruce Coast and Coats Land were to be incorporated into Norwegian territory.[11]

Later developments

.jpg)

The Norwegian–British–Swedish Antarctic Expedition of 1949–52 was the first international scientific expedition in Antarctica. The expedition established its winter quarters at a base called Maudheim at 71°S, 11°W, and mapped much of western Queen Maud Land.[25][26] During the International Geophysical Year (1957–1958), year-round stations were established in Queen Maud Land by Norway, the Soviet Union, Belgium and Japan. The Norwegian expedition continued with topographical mapping, while the others started geophysical and geological research. Norway's Norway Station was lent to South Africa following the withdrawal of the Norwegian expedition in 1960. South Africa later built the SANAE station, near the now-defunct Norway Station. The Soviet Union, and later Russia, has maintained continual operations, although it moved from Lazarev Station to Novolazarevskaya Station. Japan has been based at its Showa Station since 1957, except for a hiatus of a few years. Belgium closed its King Baudouin Station in 1961, though it mounted limited operations in cooperation with the Netherlands in 1964–66. The United States established the temporary Plateau Station in 1966.[11]

In 1948, the newly created Norwegian Polar Institute was assigned the administration of Norwegian territories in the Arctic and Antarctic, including Queen Maud Land.[16] Norway sent two major expeditions to the territory in the 1940s and 1950s, but its efforts declined after that.[12] On 21 June 1957, Queen Maud Land became subject to Norwegian sovereignty as a dependency (biland),[5] and the Antarctic Treaty officially came into force on 23 June 1961.[27] Norwegian activity during the 1960s was limited to some minor co-expeditions with the United States, until it gradually picked up again following a larger expedition to western Queen Maud Land and the eastern Weddell Sea by the Norwegian Polar Institute in 1976–77.[11][12]

Founded in 1978,[28] the Polar Affairs Department of the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police, headquartered in Oslo, has been assigned the administration of the Norwegian polar areas including Queen Maud Land.[29] Since 1979, the Norwegian Polar Institute has been a directorate under the Ministry of the Environment.[30]

In 1992, an expedition by Ivar Tollefsen made the first ascents of several mountains, including the tallest, Jøkulkyrkja.[11] Norway established the summer station Troll in 1989–90.[11][12] In 2003, Minister of the Environment Børge Brende was the first Norwegian minister to visit Queen Maud Land, and he soon allocated funds to expand the Troll station.[31] Troll was upgraded to a year-round station in 2005[11][12] as part of the centenary of Norway's independence.[31] Among the guests were Minister of Foreign Affairs Jan Petersen and Minister of the Environment Knut Arild Hareide,[31] and Troll was officially opened by Queen Sonja of Norway, the first queen to ever visit Antarctica.[7][32] In 2008, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg, accompanied by forty officials, scientists and reporters, became the first Norwegian prime minister to visit Queen Maud Land. He personally named three mountains around the Troll station where he was based, although he chose to sleep outdoors in a tent, rather than in a bed inside. He said the purposes of the visit were to claim Norway's possessions in Antarctica, as well as to learn more about the climate research at Troll, which he said was key to better understanding of global climate change.[7][32]

In 2015, King Harald V became the world's first reigning monarch to visit Antarctica when he went to Queen Maud Land.[33]

Legal status

Like all other territorial claims in Antarctica, the Norwegian claim of Queen Maud Land (along with its claim of Peter I Island) is subject to the Antarctic Treaty System. The treaty makes clear that Antarctica can only be used for peaceful purposes and assures the freedom of scientific activity. It promotes international scientific cooperation and bans any nuclear-related activities. Although territorial claims are not invalidated by the treaty, all claims under Article III of the treaty are in effect suspended as long as it is in force.[30][34][35] Norway, Australia, France, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have all mutually recognised each other's claims in Antarctica.[36] But there is a question on the actual boundaries of the claim, since the initial Norwegian demarcations both towards the South Pole and into the sea were left unclear. Apparently this was to avoid accepting use of the "sector principle" for Arctic Ocean claims by the Soviet Union.[37]

Norwegian administration of Queen Maud Land is controlled by the Polar Affairs Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Police, located in Oslo.[38] The annexation of the territory is regulated by the Dependency Act of 24 March 1933; Queen Maud Land was added on 21 June 1957. It establishes that Norwegian criminal law, private law and procedural law applies to the territory, in addition to other laws that explicitly state they are valid in the territory. Furthermore, it establishes that all the land belongs to the state, and prohibits both nuclear detonations and the storage of nuclear waste.[39]

Since 5 May 1995, Norwegian law has required all Norwegian activity in Antarctica to follow international environmental law for Antarctica. Norwegian citizens who plan activities in Queen Maud Land must therefore report to the Norwegian Polar Institute, which may prohibit any non-compliant activity. Those who visit Queen Maud Land must follow laws regarding protection of nature, treatment of waste, pollution and insurance for search and rescue operations.[40]

Fauna and flora

There are three types of birds around Troll: the Antarctic petrel, the snow petrel and the south polar skua. The Antarctic petrel lives on the sea ice for most of the year, with the exception of its breeding season (in Antarctica, from November to February), when it moves to the inland mountains and nunataks.[41] The 3.9-square-kilometre (1.5 sq mi) area of ice-free cliffs in Princess Astrid Coast called Svarthamaren Mountain hosts Antarctica's largest known inland colony of breeding seabirds, almost 1 million (250,000 pairs) Antarctic petrels.[12][41] Many snow petrels and south polar skuas also breed in this area. Snow petrels are generally spread out in smaller colonies throughout the mountainous areas of Queen Maud Land. During the breeding season, the south polar skua feeds exclusively upon the eggs, as well as both young and adult birds, of both petrel species.[41]

The emperor penguin has some of its breeding places concentrated in Queen Maud Land.[42] All four of the true Antarctic seals, namely the Weddell seal, leopard seal, crabeater seal and Ross seal, can be found in the King Haakon VII Sea off Queen Maud Land.[43][44] The Ross seal is notably found in its greatest numbers in the King Haakon VII Sea.[45]

The nunatak areas have a scarcity of flora, limited to lichen, bryophyte and algae. Flowering plants are not found there. The Norwegian Polar Institute has not registered the occurrence of any threatened or rare plants or animals in Queen Maud Land, the known ones thus existing in healthy populations.[43]

Research stations

Queen Maud Land is currently home to 12 research stations: the Norwegian Troll and Tor stations; Russia's Novolazarevskaya Station; South Africa's SANAE IV; the Swedish Wasa; the Finnish Aboa; the German Neumayer-Station III and Kohnen; India's Maitri station; the Japanese Showa Station and Dome Fuji Station; and Belgium's Princess Elisabeth Base. These stations' total summer population is approximately 494, but with considerably fewer in winter.

These stations are connected by the Dronning Maud Land Air Network Project (DROMLAN), which is a cooperative agreement for transportation between eleven nations with research stations in East Antarctica. Long-range aircraft fly between Cape Town, South Africa and either the Troll Airfield, located at the Troll research station, or the runway at the Novolazarevskaya Station. From these two main airfields, smaller aircraft may fly further to other Antarctic destinations.[7]

Norway's Troll station serves as a major hub of the DROMLAN network through the Troll Airfield.[7] Research at Troll include air and atmospheric measurements,[46] monitoring of greenhouse gases and bird colonies, as well as meteorological and climate research.[31] The other Norwegian station, Tor, was established for researching birds at the breeding colony in Svarthamaren Mountain.[41]

Activities conducted by Russia's Novolazarevskaya Station include environmental monitoring, geodesy/mapping, geomagnetic and meteorological observations, glaciology, biology, ionospheric / auroral observations, limnology, geology, geophysics and seismology.[47]

South Africa's SANAE IV station, the successor to three former stations, was completed in 1997. Research at SANAE IV include invasion biology/ecology, geology, geomorphology and atmospheric sciences. Its facilities include a small hospital and a two-helicopter hangar.[48]

The Swedish Wasa station and the Finnish Aboa station together make up the Nordenskiöld Base, and cooperate in research and logistics. Research carried out includes geodesy/mapping, glaciology, human biology, meteorological observations, geology and geophysics.[49]

The German Neumayer-Station III, finished in 2009, succeeded two former stations that were buried by snow and ice.[1] It conducts geophysical, meteorological and seismological research, as well as air chemistry measurements and atmospheric ozone monitoring.[50] Germany's other station, Kohnen, was opened as part of a major ice-drilling project.[51]

The Maitri station succeeded the Dakshin Gangotri station in 1989, India's first Antarctic base.[52] Maitri's research focus on geology, and the study of the supercontinent Gondwana, when India and Antarctica belonged to the same landmass. It also includes low-temperature engineering research that is relevant to conditions in the Himalayas.[53]

The Showa Station is Japan's main research station in Antarctica. A vast array of research is conducted there, including upper atmosphere physics, meteorology, seismology, gravimetry, geodesy/mapping, oceanography, glaciology, geology, marine and terrestrial biology, and medical research.[54] Japan's other station, Dome Fuji Station was opened as part of a major ice-coring project.[2] It mainly studies climate change and conducts deep drilling and atmospheric observations.[55]

Belgium's Princess Elisabeth Base was established as a project to promote polar sciences, as well as to demonstrate the possibility of building a zero emission station.[56] Research is conducted by an international team of scientists, studying climatology, glaciology and microbiology.[57]

Notes

- The Norwegian name, Dronning Maud Land, is also used by English speakers.[1][2] This derives from a 1974 agreement between Norway and the United Kingdom, in which it was agreed to not translate the place names in each other's respective claims. Informal corresponding agreements are also in effect with Australia, New Zealand and France.[3]

- At the time of the claim, Norway did not validate the sector method of demarcating polar territory. This was in line with Norwegian claims in the Arctic and hence to avoid compromising Norway's position with regard to the former Soviet Union and present-day Russia. In the 2015 White Paper No. 32 (2014–2015) "Norwegian Interests and Policy in Antarctica" the Foreign Ministry confirmed that while Norway rejected the sector method of delimiting claims it was not intended create a difference in interpreation of the Norwegian claim in the Antarctica; White Paper No. 19 (1939) had stated that the purpose of the annexation was to annex "land which is currently terra nullius and that only Norwegians have researched and mapped".

- Russian cartographers however interpose three marginal seas along the coast, namely the Lazarev Sea, Riiser-Larsen Sea and the Cosmonaut Sea.[10]

- Although some, notably Norwegian writer Bjarne Aagaard and German geographer Ernst Herrmann, have claimed that Germany never actually occupied the territory, it is well documented that Germany issued a decree about the establishment of a German Antarctic Sector called New Swabia after the expedition's return in August 1939.[20]

References

- Rubin, 2008, p. 304.

- Mills, 2003, p. 540.

- Ørvoll, Oddveig Øien. "Kartlegginga av Antarktis: Internasjonale avtaler" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- "Minifacts about Norway 2011: 2. Geography, climate and environment". Statistics Norway. 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Forutsetninger for Antarktistraktaten: Dronning Maud Lands statsrettslige stilling – "utviklingen" frem til 1957". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Rapp, Ole Magnus (21 September 2015). "Norge utvider Dronning Maud Land helt frem til Sydpolen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway: Aftenposten. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

…formålet med anneksjonen var å legge under seg det landet som til nå ligger herreløst og som ingen andre enn nordmenn har kartlagt og gransket. Norske myndigheter har derfor ikke motsatt seg at noen tolker det norske kravet slik at det går helt opp til og inkluderer polpunktet.

- Rubin, 2008, p. 305.

- "Queen Maud Land". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Utenriksdepartementet (12 June 2015). "Meld. St. 32 (2014–2015)". Regjeringa.no. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Stonehouse, pp. 155–156.

- Gjeldsvik, Tore. "Dronning Maud Land". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- "Dronning Maud Land" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Shirihai, Hadoram; Cox, John (2008). The complete guide to Antarctic wildlife: birds and marine mammals of the Antarctic continent and the Southern Ocean. Princeton University. p. 517. ISBN 978-0691136660.

- Elvevold, Synnøve (2005). "Geologi i Antarktis" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 18 July 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Heldal, 2011, p. 10.

- Heldal, 2011, p. 11.

- Joyner, 1992, p. 47.

- Hatherton, Trevor (1965). Antarctica. Taylor & Francis. The New Zealand Antarctic Society. p. 21.

- "1911". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Widerøe, Turi (2008). "Annekteringen av Dronning Maud Land". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Murphy, 2002, p. 192.

- Murphy, 2002, p. 204.

- Hince, Bernadette (2000). The Antarctic dictionary: a complete guide to Antarctic English. CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-9577471-1-1.

- "Forutsetninger for Antarktistraktaten". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Molle, Kris (2 December 2010). "Maudheim". Polar Conservation Organisation. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Maudheim-ekspedisjonen (NBSX)". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Forutsetninger for Antarktistraktaten: Antarktistraktaten". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Polar Affairs Department". Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Polar Affairs Department". Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Molle, Kris (29 October 2010). "Norway and Antarctica". Polar Conservation Organisation. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Jaklin, G. S. (2005). "Norge: Året rundt i Antarktis" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 18 July 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jenssen, Elin Vinje (22 January 2008). "Stoltenberg named mountains in Antarctica". Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "King Harald visits Antarctic namesake". The Local. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

"Sun shines for king in Antarctica". Newsinenglish.no. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

"King Harald begins Antarctic visit". The Norway Post. NRK/Aftenposten. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015. - "Antarktistraktaten" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "The Antarctic Treaty (ATS}". Ats.aq. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- National Research Council (U.S.) Polar Research Board (1986). Antarctic treaty system: an assessment. National Academies Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-309-03640-5.

- Joyner, Christopher C. (1992). Antarctica and the Law of the Sea. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-0792318231. Retrieved 14 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- "Polar Affairs Department". Norwegian Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "Lov om Bouvet-øya, Peter I's øy og Dronning Maud Land m.m. (bilandsloven)". Lovdata (in Norwegian). 13 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "Antarktis". Norwegian Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Strøm, Hallvard. "Faktaark: Sjøfuglene i Antarktis" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Rubin, 2008, p. 120.

- "Dronning Maud Land" (in Norwegian). Miljøstatus i Norge. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Joyner, 1992, p. 26.

- Stone, David (1995). Seals. International Union for Conservation of Nature. p. 19. ISBN 978-2-8317-0049-6.

- "Antarktis: Troll får nye krefter". Norwegian Institute for Air Research. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- Molle, Kris (2 December 2010). "Novolazarevskaya". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Rubin, 2008, pp. 304–305.

- Molle, Kris (2 November 2010). "Aboa". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Molle, Kris (2 December 2010). "Neumayer". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Mills, 2003, p. 259.

- Rubin, 2008, p. 306.

- McGonigal, 2009, p. 110.

- "Syowa". Polar Conservation Organisation. 3 November 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Molle, Kris (3 November 2010). "Dome Fuji". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Princess Elisabeth Antarctica". Princess Elisabeth Antarctica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Molle, Kris (2 November 2010). "Princess Elisabeth". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

Bibliography

- Heldal, Tom (2011). Abstracts and Proceedings of the Geological Society of Norway: Vinterkonferansen 2011 (PDF). Stavanger: Geological Society of Norway. ISBN 978-82-92394-62-5.

- Joyner, Christopher C. (1992). Antarctica and the law of the sea. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7923-1823-1.

- McGonigal, David (2009). Antarctica: Secrets of the Southern Continent. frances lincoln ltd. ISBN 978-0-7112-2980-8.

- Mills, William James (2003). Exploring Polar frontiers: A–L, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-422-0.

- Murphy, David Thomas (2002). German exploration of the polar world: a history, 1870–1940. University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-0-8032-3205-1.

- Rubin, Jeff (2008). Antarctica. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-549-9.

- Stonehouse, Bernard (2002). Encyclopedia of Antarctica and the southern oceans. John Wiley and Son. ISBN 978-0-471-98665-2.

.svg.png)