Goa

Goa (/ˈɡoʊə/ (![]()

Goa | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Colva Beach, Church and Convent of St. Francis of Assisi, Basilica of Bom Jesus, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church, Goa and Gallery de Fontainhas | |

| Motto(s): Sarve Bhadrāni Paśyantu Mā Kaścid Duhkhabhāg bhavet (May everyone see goodness, may none suffer any pain) | |

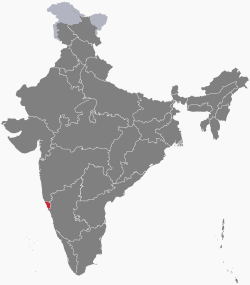

Location of Goa in India | |

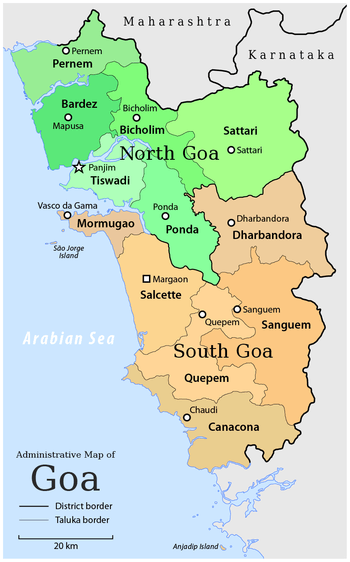

Map of Goa | |

| Coordinates (Panaji): 15.50°N 73.83°E | |

| Country | |

| Formation of state | 30 May 1987 |

| Capital | Panaji (Panjim) |

| Largest city | Vasco da Gama |

| Districts | 2 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Goa |

| • Governor | Satya Pal Malik (BJP) |

| • Chief Minister | Pramod Sawant (BJP) |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (40 seats) |

| • Parliamentary constituency | Rajya Sabha 1 Lok Sabha 2 |

| • High Court | Bombay High Court, Goa Bench |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,702 km2 (1,429 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 28th |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 1,458,545[1] |

| • Rank | 26th |

| Demonym(s) | Goan, Goenkār |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-GA |

| HDI (2018) | |

| Literacy | 88.70% (3rd) |

| Official language | |

| Website | www |

| ^* Konkani in Devanagari script is the sole official language but Marathi and English are also allowed to be used for any or all official purposes.[3][4] | |

Panaji is the state's capital, while Vasco da Gama is its largest city. The historic city of Margao still exhibits the cultural influence of the Portuguese, who first landed in the early 16th century as merchants and conquered it soon thereafter. Goa was a former state of the Portuguese Empire. The Portuguese overseas territory of Portuguese India existed for about 450 years until it was annexed by India in 1961.[8][9] Its majority and official language is Konkani.

Goa is visited by large numbers of international and domestic tourists each year for its white sand beaches, nightlife, places of worship and World Heritage-listed architecture. It has rich flora and fauna, owing to its location on the Western Ghats range, a biodiversity hotspot.

Etymology

In ancient literature, Goa was known by many names, such as Gomanchala, Gopakapattana, Gopakapattam, Gopakapuri, Govapuri, Govem, and Gomantak.[10] Other historical names for Goa are Sindapur, Sandabur, and Mahassapatam.[11]

History

Prehistory

Rock art engravings found in Goa exhibit the earliest traces of human life in India.[12] Goa, situated within the Shimoga-Goa Greenstone Belt in the Western Ghats (an area composed of metavolcanics, iron formations and ferruginous quartzite), yields evidence for Acheulean occupation.[13] Rock art engravings (petroglyphs) are present on laterite platforms and granite boulders in Usgalimal near the west flowing Kushavati river and in Kajur.[14] In Kajur, the rock engravings of animals, tectiforms and other designs in granite have been associated with what is considered to be a megalithic stone circle with a round granite stone in the centre.[15] Petroglyphs, cones, stone-axe, and choppers dating to 10,000 years ago have been found in various locations in Goa, including Kazur, Mauxim, and the Mandovi-Zuari basin.[16] Evidence of Palaeolithic life is visible at Dabolim, Adkon, Shigao, Fatorpa, Arli, Maulinguinim, Diwar, Sanguem, Pilerne, and Aquem-Margaon. Difficulty in carbon dating the laterite rock compounds poses a problem for determining the exact time period.[17]

Early Goan society underwent radical change when Indo-Aryan and Dravidian migrants amalgamated with the aboriginal locals, forming the base of early Goan culture.[18]

Early history

In the 3rd century BC, Goa was part of the Maurya Empire, ruled by the Buddhist emperor, Ashoka of Magadha. Buddhist monks laid the foundation of Buddhism in Goa. Between the 2nd century BC and the 6th century AD, Goa was ruled by the Bhojas of Goa. Chutus of Karwar also ruled some parts as feudatories of the Satavahanas of Kolhapur (2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD), Western Kshatrapas (around 150 AD), the Abhiras of Western Maharashtra, Bhojas of the Yadav clans of Gujarat, and the Konkan Mauryas as feudatories of the Kalachuris.[19] The rule later passed to the Chalukyas of Badami, who controlled it between 578 and 753, and later the Rashtrakutas of Malkhed from 753 to 963. From 765 to 1015, the Southern Silharas of Konkan ruled Goa as the feudatories of the Chalukyas and the Rashtrakutas.[20] Over the next few centuries, Goa was successively ruled by the Kadambas as the feudatories of the Chalukyas of Kalyani. They patronised Jainism in Goa.[21]

In 1312, Goa came under the governance of the Delhi Sultanate. The kingdom's grip on the region was weak, and by 1370 it was forced to surrender it to Harihara I of the Vijayanagara empire. The Vijayanagara monarchs held on to the territory until 1469, when it was appropriated by the Bahmani sultans of Gulbarga. After that dynasty crumbled, the area fell into the hands of the Adil Shahis of Bijapur, who established as their auxiliary capital the city known under the Portuguese as Velha Goa (or Old Goa).[22]

.jpg) The Mahadev Temple, attributed to the Kadambas of Goa; in what is today Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park.

The Mahadev Temple, attributed to the Kadambas of Goa; in what is today Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park.- Gold coins issued by the Kadamba king of Goa, Shivachitta Paramadideva. Circa 1147–1187 CE.

Portuguese period

In 1510, the Portuguese defeated the ruling Bijapur sultan Yusuf Adil Shah with the help of a local ally, Timayya. They set up a permanent settlement in Velha Goa. This was the beginning of Portuguese colonial rule in Goa that would last for four and a half centuries, until its annexation in 1961. The Goa Inquisition, a formal tribunal, was established in 1560, and was finally abolished in 1812.[23]

In 1843 the Portuguese moved the capital to Panaji from Velha Goa. By the mid-18th century, Portuguese Goa had expanded to most of the present-day state limits. Simultaneously the Portuguese lost other possessions in India until their borders stabilised and formed the Estado da Índia Portuguesa or State of Portuguese India.

Contemporary period

After India gained independence from the British in 1947, India requested that Portuguese territories on the Indian subcontinent be ceded to India. Portugal refused to negotiate on the sovereignty of its Indian enclaves. On 19 December 1961, the Indian Army invaded with Operation Vijay resulting in the annexation of Goa, and of Daman and Diu islands into the Indian union. Goa, along with Daman and Diu, was organised as a centrally administered union territory of India.[24] On 30 May 1987, the union territory was split, and Goa was made India's twenty-fifth state, with Daman and Diu remaining a union territory.[25]

Geography and climate

Geography

Goa encompasses an area of 3,702 km2 (1,429 sq mi). It lies between the latitudes 14°53′54″ N and 15°40′00″ N and longitudes 73°40′33″ E and 74°20′13″ E.

Goa is a part of the coastal country known as the Konkan, which is an escarpment rising up to the Western Ghats range of mountains, which separate it from the Deccan Plateau. The highest point is the Sonsogor, with an altitude of 1,167 metres (3,829 ft). Goa has a coastline of 160 km (99 mi).

Goa's seven major rivers are the Zuari, Mandovi, Terekhol, Chapora, Galgibag, Kumbarjua canal, Talpona and the Sal.[26] The Zuari and the Mandovi are the most important rivers, interspaced by the Kumbarjua canal, forming a major estuarine complex.[26] These rivers are fed by the Southwest monsoon rain and their basin covers 69% of the state's geographical area.[26] These rivers are some of the busiest in India. Goa has more than 40 estuarine, eight marine, and about 90 riverine islands. The total navigable length of Goa's rivers is 253 km (157 mi). Goa has more than 300 ancient water-tanks built during the rule of the Kadamba dynasty and over 100 medicinal springs.

The Mormugao harbour on the mouth of the River Zuari is one of the best natural harbours in South Asia.

Most of Goa's soil cover is made up of laterites rich in ferric-aluminium oxides and reddish in colour. Further inland and along the riverbanks, the soil is mostly alluvial and loamy. The soil is rich in minerals and humus, thus conducive to agriculture. Some of the oldest rocks in the Indian subcontinent are found in Goa between Molem and Anmod on Goa's border with Karnataka. The rocks are classified as Trondjemeitic Gneiss estimated to be 3,600 million years old, dated by rubidium isotope dating. A specimen of the rock is exhibited at Goa University.

- Dudhsagar Falls at Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park

Dudhsagar Waterfalls in August.

Dudhsagar Waterfalls in August. Train passing next to the Dudhsagar Falls.

Train passing next to the Dudhsagar Falls.- Lower half of Dudhsagar Falls.

Climate

Goa features a tropical monsoon climate under the Köppen climate classification. Goa, being in the tropical zone and near the Arabian Sea, has a hot and humid climate for most of the year. The month of May is usually the hottest, seeing daytime temperatures of over 35 °C (95 °F) coupled with high humidity. The state's three seasons are: Southwest monsoon period (June – September), post-monsoon period (October – January) and fair weather period (February – May).[26] Over 90% of the average annual rainfall (120 inches) is received during the monsoon season.[26]

| Climate data for Goa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.4 (81.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.2 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.2 (0.05) |

11.8 (0.46) |

112.7 (4.44) |

868.2 (34.18) |

994.8 (39.17) |

512.7 (20.19) |

251.9 (9.92) |

124.8 (4.91) |

30.9 (1.22) |

16.7 (0.66) |

2,926 (115.2) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 21.9 | 27.2 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 90.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 313.1 | 293.8 | 291.4 | 288.0 | 297.6 | 126.0 | 105.4 | 120.9 | 177.0 | 248.0 | 273.0 | 300.7 | 2,834.9 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Hong Kong Observatory[28] for sunshine and mean temperatures | |||||||||||||

Subdivisions

The state is divided into two districts: North Goa and South Goa. Each district is administered by a district collector, appointed by the Indian government.

Panaji is the headquarters of North Goa district and is also the capital of Goa.

North Goa is further divided into three subdivisions – Panaji, Mapusa, and Bicholim; and five talukas (subdistricts) – Tiswadi/Ilhas de Goa (Panaji), Bardez (Mapusa), Pernem, Bicholim, and Sattari (Valpoi).

Margao is the headquarters of South Goa district.

South Goa is further divided into five subdivisions – Ponda, Mormugao-Vasco, Margao, Quepem, and Dharbandora; and seven talukas – Ponda, Mormugao, Salcete (Margao), Quepem, and Canacona (Chaudi), Sanguem, and Dharbandora. (Ponda taluka was shifted from North Goa to South Goa in January 2015).

Goa's major cities include Panaji, Margao, Vasco, Mapusa, Ponda, Bicholim, and Valpoi.

Panaji has the only Municipal Corporation in Goa.

There are thirteen Municipal Councils: Margao, Mormugao (including Vasco), Pernem, Mapusa, Bicholim, Sanquelim, Valpoi, Ponda, Cuncolim, Quepem, Curchorem, Sanguem, and Canacona. Goa has a total number of 334 villages.[29]

Government and politics

The politics of Goa are a result of the uniqueness of this region due to 450 years of Portuguese rule, in comparison to three centuries of British colonialism experienced by the rest of India. The Indian National Congress was unable to achieve electoral success in the first two decades after the State's incorporation into India.[30] Instead, the state was dominated by the regional political parties like Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party and the United Goans Party.[31]

Government

In the Parliament of India, Goa has two seats in the Lok Sabha (House of the People), one representing each district, and one seat in the Rajya Sabha (Council of the States).

Goa's administrative capital is Panaji in English, Pangim in Portuguese, and Ponjê in the local language. It lies on the left bank of the Mandovi. The seat of the Goa Legislative Assembly is in Porvorim, across the Mandovi from Panaji. As the state comes under the Bombay High Court, Panaji has a bench in it. Unlike other states, which follow the British Indian model of civil laws framed for individual religions, the Portuguese Goa civil code, a uniform code based on the Napoleonic code, has been retained in Goa.

Goa has a unicameral legislature, the Goa Legislative Assembly, of 40 members, headed by a speaker. The Chief Minister heads the executive, which is made up from the party or coalition elected with a majority in the legislature. The Governor, the head of the state, is appointed by the President of India. After having stable governance for nearly thirty years up to 1990, Goa is now notorious for its political instability having seen fourteen governments in the span of the fifteen years between 1990 and 2005.[32]

In March 2005, the assembly was dissolved by the Governor and President's Rule was declared, which suspended the legislature. A by-election in June 2005 saw the Indian National Congress coming back to power after winning three of the five seats that went to polls. The Congress Party and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are the two largest parties in the state. In the assembly poll of 2007, the INC-led coalition won and formed the government.[33] In the 2012 Vidhan Sabha Elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party along with the Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party won a clear majority, forming the new government with Manohar Parrikar as the Chief Minister. Other parties include the United Goans Democratic Party, the Nationalist Congress Party.[34]

In the 2017 assembly elections, the Indian National Congress gained the most seats, with the BJP coming in second. However, no party was able to gain a majority in the 40 member house. The BJP was invited to form the Government by Governor Mridula Sinha. The Congress claimed the use of money power on the part of the BJP and took the case to the Supreme Court. However, the Manohar Parikkar led Government was able to prove its majority in the Supreme Court mandated "floor test".[35][36][37]

Flora and fauna

Equatorial forest cover in Goa stands at 1,424 km2 (549.81 sq mi),[10] most of which is owned by the government. Government-owned forest is estimated at 1,224.38 km2 (472.74 sq mi) whilst private is given as 200 km2 (77.22 sq mi). Most of the forests in the state are located in the interior eastern regions of the state. The Western Ghats, which form most of eastern Goa, have been internationally recognised as one of the biodiversity hotspots of the world. In the February 1999 issue of National Geographic Magazine, Goa was compared with the Amazon and the Congo basins for its rich tropical biodiversity.

Goa's wildlife sanctuaries boast of more than 1512 documented species of plants, over 275 species of birds, over 48 kinds of animals and over 60 genera of reptiles.[38]

Goa is also known for its coconut cultivation. The coconut tree has been reclassified by the government as a palm (like a grass), enabling farmers and real estate developers to clear land with fewer restrictions.

Rice is the main food crop, and pulses (legume), Ragi (Finger Millet) and other food crops are also grown. Main cash crops are coconut, cashewnut, arecanut, sugarcane and fruits like pineapple, mango and banana.[10] Goa's state animal is the Gaur, the state bird is the Ruby Throated Yellow Bulbul, which is a variation of Black-crested Bulbul, and the state tree is the Matti (Asna).

The important forests products are bamboo canes, Maratha barks, chillar barks and the bhirand. Coconut trees are ubiquitous and are present in almost all areas of Goa barring the elevated regions. A variety of deciduous trees, such as teak, Sal tree, cashew and mango trees are present. Fruits include jackfruit, mango, pineapple and "black-berry" ("podkoam" in Konkani language). Goa's forests are rich with medicinal plants.

Foxes, wild boar and migratory birds are found in the jungles of Goa. The avifauna (bird species) includes kingfisher, myna and parrot. Numerous types of fish are also caught off the coast of Goa and in its rivers. Crab, lobster, shrimp, jellyfish, oysters and catfish are the basis of the marine fishery. Goa also has a high snake population. Goa has many famous "National Parks", including the renowned Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary on the island of Chorão. Other wildlife sanctuaries include the Bondla Wildlife Sanctuary, Molem Wildlife Sanctuary, Cotigao Wildlife Sanctuary, Madei Wildlife Sanctuary, Netravali Wildlife Sanctuary, and Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary.

Goa has more than 33% of its geographic area under government forests (1224.38 km²) of which about 62% has been brought under Protected Areas (PA) of Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Park. Since there is a substantial area under private forests and a large tract under cashew, mango, coconut, etc. plantations, the total forest and tree cover constitutes 56.6% of the geographic area.

Economy

| Gross State Domestic Product (in millions of Rupees)[39] | |

| Year | GSDP |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 3,980 |

| 1985 | 6,550 |

| 1990 | 12,570 |

| 1995 | 33,190 |

| 2000 | 76,980 |

| 2010 | 150,000 |

Goa's state domestic product for 2017 is estimated at $11 billion at current prices. Goa is India's richest state with the highest GDP per capita – two and a half times that of the country – with one of its fastest growth rates: 8.23% (yearly average 1990–2000).[40] Tourism is Goa's primary industry: it gets 12%[41] of foreign tourist arrivals in India. Goa has two main tourist seasons: winter and summer. In winter, tourists from abroad (mainly Europe) come, and summer (which, in Goa, is the rainy season) sees tourists from across India. Goa's net state domestic product (NSDP) was around US$7.24 billion in 2015–16.[42]

The land away from the coast is rich in minerals and ores, and mining forms the second largest industry. Iron, bauxite, manganese, clays, limestone, and silica are mined. The Mormugao port handled 31.69 million tonnes of cargo last year, which was 39% of India's total iron ore exports. Sesa Goa (now owned by Vedanta Resources) and Dempo are the lead miners. Rampant mining has been depleting the forest cover as well as posing a health hazard to the local population. Corporations are also mining illegally in some areas. During 2015–16, the total traffic handled by Mormugao port was recorded to be 20.78 million tonnes.

Agriculture, while of shrinking importance to the economy over the past four decades, offers part-time employment to a sizeable portion of the populace. Rice is the main agricultural crop, followed by areca, cashew, and coconut. Fishing employs about 40,000 people, though recent official figures indicate a decline of the importance of this sector and also a fall in catch, due perhaps, to traditional fishing giving way to large-scale mechanised trawling.

Medium scale industries include the manufacturing of pesticides, fertilisers, tyres, tubes, footwear, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, wheat products, steel rolling, fruits and fish canning, cashew nuts, textiles, brewery products.

Currently, there are 16 planned SEZs in Goa. The Goa government has recently decided to not allow any more Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Goa after strong opposition to them by political parties and the powerful Goa Catholic Church.[43]

Goa is also notable for its low priced beer, wine, and spirits prices due to its very low excise duty on alcohol. Another main source of cash inflow to the state is remittance, from many of its citizens who work abroad, to their families. It is said to have some of the largest bank savings in the country.

Goa is the second state in India to achieve a 100 percent automatic telephone system with a solid network of telephone exchanges. As of September 2017, Goa had a total installed power generation capacity of 547.88 MW. Goa is also one of the few states in India to achieve 100 percent rural electrification.[44]

- Commercial area in Panaji.

Demographics

Population

| Population growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1951 | 547,000 | — | |

| 1961 | 590,000 | 7.9% | |

| 1971 | 795,000 | 34.7% | |

| 1981 | 1,008,000 | 26.8% | |

| 1991 | 1,170,000 | 16.1% | |

| 2001 | 1,347,668 | 15.2% | |

| 2011 | 1,458,545 | 8.2% | |

A native of Goa is called a Goan. Goa has a population of 1.459 million residents as of 2011,[45] making it India's fourth smallest (after Sikkim, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh). The population has a growth rate of 8.23% per decade. There are 394 people for each square kilometre of land which is higher than national average 382 per km2. Goa is the state with highest proportion of urban population with 62.17% of the population living in urban areas. The sex ratio is 973 females to 1,000 males. The birth rate is 15.70 per 1,000 people in 2007. Goa also is the state with lowest proportion of Scheduled Tribes at 0.04%.[46] A relatively small Goan-Portuguese mixed race population resulted from Portuguese colonisation, one estimate being that less than 100 mestiço families left in 1961 when Portugal lost the colony.[47] Estimates put the migrant, or non-Goan, population at 20% of the population, with a state government study projecting that by 2021 the migrant community will outnumber the native population.[48]

Languages

The Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act, 1987 makes Konkani in the Devanagari script the sole official language of Goa, but provides that Marathi may also be used "for all or any of the official purposes". Portuguese was the sole official language during Portuguese colonial rule. The government also has a policy of replying in Marathi to correspondence received in Marathi.[50] Whilst there have been demands for according Konkani in the Roman script official status in the state, there is widespread support for keeping Konkani as the sole official language of Goa.[51] It is however notable to mention that the entire liturgy and communication of the Catholic church in Goa is done solely in the Roman script of Konkani.

Konkani is spoken as a native language by about 66.11% of the people in the state but almost all Goans can speak and understand Konkani. Other linguistic minorities in the state per the 2011 census are speakers of Marathi (10.89%), Hindi (10.29%), Kannada (4.66%) and Urdu (2.83%).[52]

Historically, Konkani was neither the official or administrative language used by the various rulers of the State. Under the Kadambas (c. 960 – 1310) the court language was Kannada, a Dravidian language, and when under Muslim rule (1312-1370 and 1469-1510), the official and cultural language was Persian; various stones in the Goa Archaeological Museum from the period are inscribed in Kannada and Persian.[53] During the intervening periods of Muslim rule, the Vijayanagara control of the State mandated the use of Kannada and Telugu, both Dravidian languages.[53]

Religion

Religion in Goa (2011)[54]

According to the 2011 census, in a population of 1,458,545 people, 66.1% were Hindu, 25.1% were Christian, 8.3% were Muslim and 0.1% were Sikh.[54]

Due to the economic decline of Portuguese India from the 18th century, there was a large-scale migration of Goan Catholics. The local Indian Christians were called "indiacatos" and the mixed population, mestiços by the Portuguese. The population moved from 64.5% Christian and 35% Hindu in 1851 to 50% Christian and 50% Hindu in 1900, with a steady increase in the Hindu proportion from then onwards.[55]

The Catholics in Goa state and Daman and Diu union territory are served by the Metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Goa and Daman, the primatial see of India, in which the titular Patriarchate of the East Indies is vested.

Tourism

Tourism is generally focused on the coastal areas of Goa, with decreased tourist activity inland. In 2010, there were more than 2 million tourists reported to have visited Goa, about 1.2 million of whom were from abroad.[56] As of 2013, Goa was a destination of choice for Indian and foreign tourists, particularly Britons and Russians, with limited means who wanted to party. The state was hopeful that changes could be made which would attract a more upscale demographic.[57]

Goa stands 6th in the Top 10 Nightlife cities in the world in National Geographic Travel.[58] Notable nightclubs in Goa include Chronicle, Mambos and Sinq.

One of the biggest tourist attractions in Goa is water sports. Beaches like Baga and Calangute offer jet-skiing, parasailing, banana boat rides, water scooter rides, and more. Patnem beach in Palolem stood third in CNN Travel's Top 20 Beaches in Asia.[59]

Over 450 years of Portuguese rule and the influence of the Portuguese culture presents to visitors to Goa a cultural environment that is not found elsewhere in India. Goa is often described as a fusion between Eastern and Western culture with Portuguese culture having a dominant position in the state be it in its architectural, cultural or social settings. The state of Goa is famous for its excellent beaches, churches, and temples.[60] The Bom Jesus Cathedral, Fort Aguada and a new wax museum on Indian history, culture and heritage in Old Goa are other tourism destinations.

Historic sites and neighbourhoods

Goa has two World Heritage Sites: the Bom Jesus Basilica[61] and churches and convents of Old Goa. The basilica holds the mortal remains of St. Francis Xavier, regarded by many Catholics as the patron saint of Goa (the patron of the Archdiocese of Goa is actually Saint Joseph Vaz). These are both Portuguese-era monuments and reflect a strong European character. The relics are taken down for veneration and for public viewing, per the prerogative of the Church in Goa, not every ten or twelve years as popularly thought and propagated. The last exposition was held in 2014.[62]

| Year | Total Arrivals | % Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1985 | 775,212 | |

| 1990 | 881,323 | |

| 1995 | 1,107,705 | |

| 2000 | 1,268,513 | |

| 2005 | 2,302,146 | |

| 2010 | 2,644,805 | |

| 2015 | 5,297,902 |

Goa has the Sanctuary of Saint Joseph Vaz in Sancoale. Pilar monastery which holds novenas of Venerable Padre Agnelo Gustavo de Souza from 10 to 20 November yearly. There is a claimed Marian Apparition at the Church of Saints Simon and Jude at Batim, Ganxim, near Pilar, where Goans and non-resident Goans visit. There is the statue of the bleeding Jesus on the Crucifix at the Santa Monica Convent in Velha Goa. There are churches (Igorzo), like the baroque styled Nixkollounk Gorb-Sombhov Saibinnich Igorz (Church of the Our Lady of Immaculate Conception) in Panaji, the Gothic styled Mater Dei (Dêv Matechi Igorz/ Mother of God) church in Saligao and each church having its own style and heritage, besides Kopelam/ Irmidi (chapels).

The Velhas Conquistas regions are known for Goa-Portuguese style architecture. There are many forts in Goa such as Tiracol, Chapora, Corjuem, Aguada, Reis Magos, Nanus, Mormugao, Fort Gaspar Dias and Cabo de Rama.

In many parts of Goa, mansions constructed in the Indo-Portuguese style architecture still stand, though in some villages, most of them are in a dilapidated condition. Fontainhas in Panaji has been declared a cultural quarter, showcasing the life, architecture and culture of Goa. Influences from the Portuguese era are visible in some of Goa's temples, notably the Shanta Durga Temple, the Mangueshi Temple, the Shri Damodar Temple and the Mahalasa Temple. After 1961, many of these were demolished and reconstructed in the indigenous Indian style.

Museums and science centre

Goa has three important museums: the Goa State Museum, the Naval Aviation Museum and the National Institute of Oceanography. The aviation museum is one of three in India (the others are in Delhi and Bengaluru). The Goa Science Centre is in Miramar, Panaji.[64] The National Institute of Oceanography, India (NIO) is in Dona Paula.[65] Museum of Goa is a privately owned contemporary art gallery in Pilerne Industrial Estate, near Calangute.

Culture

Having been a Portuguese territory for over 450 years, Goan culture is an interesting amalgamation of both Eastern and Western styles, with the latter having a more dominant role. The tableau of Goa showcases religious harmony by focusing on the Deepastambha, the Cross and Ghode Modni followed by a chariot. Western royal attire of kings is as much part of Goa's cultural heritage as are regional dances performed depicting a unique blend of different religions and cultures of this State. Prominent local festivals are Christmas, Easter, Carnival, Diwali, Shigmo, Chavoth, Samvatsar Padvo, Dasara etc. The Goan Carnival and Christmas-new year celebrations attract many tourists.

The Gomant Vibhushan Award, the highest civilian honour of the State of Goa, is given annually by Government of Goa since 2010.[66][67]

Dance and music

Traditional Goan art forms are Dekhnni, Fugdi, Corridinho, Mando, Dulpod and Fado.[68] Goan Catholics are fond of social gatherings and Tiatr (Teatro). As part of its Portuguese history, music is an integral part of Goan homes. It is often said that "Goans are born with music and sport". Western musical instruments like the piano, guitars and violins are widely used in most religious and social functions of the Catholics.

Goan Hindus are very fond of Natak, Bhajan and Kirtan. Many famous Indian classical singers hail from Goa, including Mogubai Kurdikar, Kishori Amonkar, Kesarbai Kerkar, Jitendra Abhisheki and Pandit Prabhakar Karekar.

Goa is also known as the origin of Goa trance.

Theatre

Natak, Tiatr (most popular) and Jagor are the chief forms of Goa's traditional performance arts. Other forms are Ranmale, Dashavatari, Kalo, Goulankala, Lalit, Kala and Rathkala. Stories from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata along with more modern social subjects are narrated with song and dance.[69][70]

"Jagor", the traditional folk dance-drama, is performed by the Hindu Kunbi and Christian Gauda community of Goa, to seek the Devine Grace for protection and prosperity of the crop. Literal meaning of Jagor is "jagran" or wakeful nights. The strong belief is that the night long performance, awakens the deities once a year and they continue to remain awake throughout the year guarding the village.

Perni Jagor is the ancient mask dance – drama of Goa, performed by Perni families, using well crafted and painted wooden masks, depicting various animals, birds, supernatural power, deities, demons, and social characters.

Gauda Jagor, is an impression of social life, that displays all the existing moods and modes of human characters. It is predominantly based on three main characters, Gharasher, Nikhandar and Parpati wearing shining dress and headgears. The performance is accompanied by vibrant tunes of Goan folk instruments like Nagara/Dobe, Ghumat, Madale, and Kansale.

In some places, Jagor performances are held with participation of both Hindus and Christian community, whereby, characters are played by Hindus and musical support is provided by Christian artistes.[71]

Tiatr (Teatro) and its artists play a major role in keeping the Konkani language and music alive. Tiatrs are conducted solely in the Roman script of Konkani as it is primarily a Christian community-based act. They are played in scenes with music at regular intervals, the scenes are portrayals of daily life and are known to depict social and cultural scenarios. Tiatrs are regularly held especially on weekends mainly at Kala Academy, Panaji, Pai Tiatrist Hall at Ravindra Bhavan, Margao and most recent shows have also started at the new Ravindra Bhavan, Baina, Vasco. Western Musical Instruments such as Drums, bass, Keyboards, and Trumpets. are part of the show and most of them are played acoustically. It is one of Goa's few art forms that is renowned across the world with performances popular among Goans in the Middle-East, Americas and Europe.

Konkani cinema

Konkani cinema is an Indian film industry, where films are made in the Konkani language, which is spoken mainly in the Indian states of Goa, Maharashtra and Karnataka and to a smaller extent in Kerala. Konkani films have been produced in Goa, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Kerala.[72]

The first full-length Konkani film was Mogacho Anvddo, released on 24 April 1950, and was produced and directed by A. L.Jerry Braganza, a native of Mapusa, under the banner of ETICA Pictures.[73][74] Hence, 24 April is celebrated as Konkani Film Day.[75]

Since 2004, starting from the 35th edition, the International Film Festival of India moved its permanent venue to Goa, it is annually held in the months of November and December.[76]

Konkani film Paltadcho manis has been included in the world's best films of 2009 list.[77]

Konkani films are eligible for the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Konkani. The most commercially successful Konkani film (as of June 2011) is O Maria directed by Rajendra Talak.[78]

In 2012, the whole new change adopted in Konkani Cinema by introducing Digital Theatrical Film "The Victim" directed by Milroy Goes.[79]

Some old Konkani films are Sukhachem Sopon, Amchem Noxib, Nirmonn, Mhoji Ghorkarn, Kortubancho Sonvsar, Jivit Amchem Oxem, Mog ani Moipas, Bhuierantlo Munis, Suzanne, Boglantt, Padri and Bhogsonne. Ujwadu is a 2011 Konkani film directed by Kasargod Chinna and produced by KJ Dhananjaya and Anuradha Padiyar.

Food

Goan prawn curry, a popular dish throughout the state.

Goan prawn curry, a popular dish throughout the state. Pork vindaloo is a popular Goan curry dish in the state and around the world.

Pork vindaloo is a popular Goan curry dish in the state and around the world. Chamuças, Goan samosas

Chamuças, Goan samosas Traditional Goan fish curry

Traditional Goan fish curry Left Tandoori lobster with fries and vegetables.

Left Tandoori lobster with fries and vegetables.

Right Tandoori prawns with sauce.

Rice with fish curry (xit koddi in Konkani) is the staple diet in Goa. Goan cuisine is famous for its rich variety of fish dishes cooked with elaborate recipes. Coconut and coconut oil are widely used in Goan cooking along with chili peppers, spices, and vinegar is used in the Catholic cuisine, giving the food a unique flavour. The Goan cuisine is heavily influenced by Portuguese cuisine.

Goan food may be divided into Goan Catholic and Goan Hindu cuisine with each showing very distinct tastes, characteristics, and cooking styles. Pork dishes such as Vindalho, Xacuti, chouriço, and Sorpotel are cooked for major occasions among the Goan Catholics. An exotic Goan vegetable stew, known as Khatkhate, is a very popular dish during the celebrations of festivals, Hindu and Christian alike. Khatkhate contains at least five vegetables, fresh coconut, and special Goan spices that add to the aroma.

Sannas, Hitt, are variants of idli and Polle, Amboli, and Kailoleo are variants of dosa; all are native to Goa. A rich egg-based, multi-layered sweet dish known as bebinca is a favourite at Christmas.

There are some places in Goa which are famous for Goa's traditional & special cuisines. Ros omelette is one of the most popular snacks and street foods in Goa, it is traditionally sold on food carts on streets.

The most popular alcoholic beverage in Goa is feni; cashew feni is made from the fermentation of the fruit of the cashew tree, while coconut feni is made from the sap of toddy palms. Urrak is another local liquor prepared from Cashew fruit. In fact the bar culture is one of the unique aspects of the Goan villages where a local bar serves as a meeting point for villagers to unwind.[80] Goa also has a rich wine culture.[81][82]

Architecture

The architecture of Goa is a combination of Goan, Ottoman and Portuguese styles. Since the Portuguese ruled and governed for four centuries, many churches and houses bear a striking element of the Portuguese style of architecture. Goan Hindu houses do not show any Portuguese influence, though the modern temple architecture is an amalgam of original Goan temple style with Dravidian, Hemadpanthi, Islamic, and Portuguese architecture.[83] The original Goan temple architecture fell into disuse as the temples were demolished by the Portuguese and the Sthapati known as Thavayi in Konkani were converted to Christianity though the wooden work and the Kavi murals can still be seen.[84]

Media and communication

Goa is served by almost all television channels available in India. Channels are received through cable in most parts of Goa. In the interior regions, channels are received via satellite dishes. Doordarshan, the national television broadcaster, has two free terrestrial channels on air.[85]

DTH (Direct To Home) TV services are available from Dish TV, Videocon D2H, Tata Sky & DD Direct Plus. The All India Radio is the only radio channel in the state that broadcasts on both FM and AM bands. Two AM channels are broadcast, the primary channel at 1287 kHz and the Vividh Bharati channel at 1539 kHz. AIR's FM channel is called FM Rainbow and is broadcast at 105.4 MHz. A number of private FM radio channels are available, Big FM at 92.7 and Radio Indigo at 91.9 MHz. There is also an educational radio channel, Gyan Vani, run by IGNOU broadcast from Panaji at 107.8 MHz. In 2006, St Xavier's College, Mapusa, became the first college in the state to launch a campus community radio station "Voice of Xavier's".[86]

Major cellular service operators include Bharti Airtel, Vodafone Essar, Idea Cellular, Telenor, Reliance Infocomm, Tata DoCoMo, BSNL CellOne and Jio.[87]

Local publications include the English language O Heraldo (Goa's oldest, once a Portuguese language paper), The Gomantak Times and The Navhind Times. In addition to these, The Times of India and The Indian Express are also received from Mumbai and Bangalore in the urban areas. The Times of India has recently started publication from Goa itself, serving the local population news directly from the state capital. Among the list of officially accredited newspapers are O Heraldo, The Navhind Times and The Gomantak Times in English; Bhaangar Bhuin in Konkani (Devanagari script); and Tarun Bharat, Gomantak, Navprabha, Goa Times, Sanatan Prabhat, Govadoot and Lokmat (all in Marathi). All are dailies. Other publications in the state include Planet Goa (English, monthly), Goa Today (English, monthly), Goan Observer (English, weekly), Vauraddeancho Ixtt (Roman-script Konkani, weekly) Goa Messenger, Vasco Watch, Gulab (Konkani, monthly), Bimb (Devanagari-script Konkani).[88]

Sports

Normally other states are fond of cricket but association football is the most popular sport in Goa and is embedded in Goan culture as a result of the Portuguese influence.[89] Its origins in the state are traced back to 1883 when the visiting Irish priest Fr. William Robert Lyons established the sport as part of a "Christian education".[89][90] On 22 December 1959 the Associação de Futebol de Goa was formed, which continues to administer the game in the state under the new name Goa Football Association.[89] Goa, along with West Bengal and Kerala[89] is the locus of football in India and is home to many football clubs in the national I-League. The state's football powerhouses include Salgaocar, Dempo, Churchill Brothers, Vasco, Sporting Clube de Goa and FC Goa. The first Unity World Cup was held in Goa in 2014. The state's main football stadium, Fatorda Stadium, is located at Margao and also hosts cricket matches.[91] The state hosted few matches of the 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup in Fatorda Stadium.[92]

A number of Goans have represented India in football and six of them, namely Samir Naik, Climax Lawrence, Brahmanand Sankhwalkar, Bruno Coutinho, Mauricio Afonso and Roberto Fernandes have all captained the national team. Goa has its own state football team and league, the Goa Professional League. It is probably the only state in India where cricket is not considered the most important of all sports. Goan's are avid football fans, particularly of the football teams from Portugal (Benfica, Sporting), and Brazil especially during major football events such as the 'European Cup' and the 'World Cup' championships. The Portuguese footballer 'Ronaldo' and Brazilian 'Neymar', are revered superstar football players in Goa.

Goa also has its own cricket team. Dilip Sardesai remains the only Goan to date to play international cricket for India.[93]

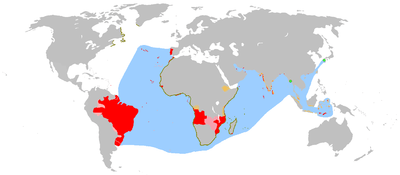

The Indian Olympic Association (IOA) has won the right to host the Asian Beach Games in Goa in 2020.[94] India (Goa) is a member of the 'Lusophony Olympic Games' which are hosted every four years in one of the Portuguese CPLP member countries, with 733 athletes from 11 countries. Most of the countries competing are countries that are members of the CPLP (Community of Portuguese Language Countries), but some are countries with significant Portuguese communities, or have a history with Portugal. This event is similar in concept to the Commonwealth Games (for members of the Commonwealth of Nations) and the Jeux de la Francophonie (for the Francophone community).

Education

Carmel College for Women is affiliated to Goa University. It was established more than 50 years to aid in closing the education gender gap.

Carmel College for Women is affiliated to Goa University. It was established more than 50 years to aid in closing the education gender gap. Goa Medical College, previously called Escola Médico–Cirúrgica de Goa.

Goa Medical College, previously called Escola Médico–Cirúrgica de Goa.

Goa had India's earliest educational institutions built with European support. The Portuguese set up seminaries for religious education and parish schools for elementary education. Founded circa 1542 by Saint Francis Xavier, Saint Paul's College, Goa was a Jesuit school in Old Goa, which later became a college. St Paul's was once the main Jesuit institution in the whole of Asia. It housed the first printing press in India and published the first books in 1556.

Medical education began in 1801 with the offering of regular medical courses at the Royal and Military Hospital in the old City of Goa. Built in 1842 as the Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de (Nova) Goa (Medical-Surgical School of Goa), Goa Medical College is one of Asia's oldest medical colleges and has one of the oldest medical libraries (since 1845).[95] It houses the largest hospital in Goa and continues to provide medical training to this day.

According to the 2011 census, Goa has a literacy rate of 87%, with 90% of males and 84% of females being literate.[96] Each taluka is made up of villages, each having a school run by the government. Private schools are preferred over government-run schools. All schools come under the Goa Board of Secondary & Higher Secondary Education, whose syllabus is prescribed by the state education department. There are also a few schools that subscribe to the all-India ICSE syllabus or the NIOS syllabus. Most students in Goa complete their high school with English as the medium of instruction. Most primary schools, however, use Konkani and Marathi (in private, but government-aided schools). As is the case in most of India, enrolment for vernacular media has seen a fall in numbers in favour of English medium education. Per a report published in The Times of India, 84% of Goan primary schools run without an administrative head.[97]

Some notable schools in Goa include Sharada Mandir School in Miramar, Loyola High School in Margao and The King's School in São José de Areal. After ten years of schooling, students join a Higher Secondary school, which offers courses in popular streams such as Science, Arts, Law and Commerce. A student may also opt for a course in vocational studies. Additionally, they may join three-year diploma courses. Two years of college is followed by a professional degree programme. Goa University, the sole university in Goa, is located in Taleigão and most Goan colleges are affiliated to it.

There are six engineering colleges in the state. Goa Engineering College and National Institute of Technology Goa are government funded colleges whereas the private engineering colleges include Don Bosco College of Engineering at Fatorda, Shree Rayeshwar Institute of Engineering and Information Technology at Shiroda, Agnel Institute of Technology and Design (AITD), Assagao, Bardez and Padre Conceicao College of Engineering at Verna. In 2004, BITS Pilani one of the premier institutes in India, inaugurated its second campus, the BITS Pilani Goa Campus, at Zuarinagar near Dabolim. The Indian Institute of Technology Goa (IIT Goa) began functioning from its temporary campus, located in Goa Engineering College since 2016. The site for permanent campus was finalised in Cotarli, Sanguem.[98]

There are colleges offering pharmacy, architecture and dentistry along with numerous private colleges offering law, arts, commerce and science. There are also two National Oceanographic Science related centres: the National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research in Vasco da Gama and the National Institute of Oceanography in Dona Paula.

Goa Institute of Management located at Sanquelim, near Panaji is one of India's premier business schools.

In addition to the engineering colleges, there are government polytechnic institutions in Panaji, Bicholim and Curchorem, and aided institutions like Father Agnel Polytechnic in Verna and the Institute of Shipbuilding Technology in Vasco da Gama which impart technical and vocational training.[99]

Other colleges in Goa include Shri Damodar College of Commerce and Economics, V.V.M's R.M. Salgaocar Higher Secondary School in Margao, G.V.M's S.N.J.A higher secondary school, Don Bosco College, D.M.'s College of Arts, Science and Commerce, St Xavier's College, Carmel College, The Parvatibai Chowgule College, Dhempe College, Damodar College, M. E. S. College of Arts & Commerce, S. S. Samiti's Higher Secondary School of Science and Rosary College of Commerce & Arts. As the result of renewed interest in the Portuguese language and culture, Portuguese at all levels of instruction is offered in many schools in Goa, largely private ones. In some cases, Goan students do student exchange programs in Portugal.

Transportation

Air

Goa International Airport, is a civil enclave at INS Hansa, a Naval airfield located at Dabolim near Vasco da Gama.[100] The airport caters to scheduled domestic and international air services. Goa has scheduled international connections to Doha, Dubai, Muscat, Sharjah and Kuwait in the Middle East by airlines like Air Arabia, Air India, GoAir, Indigo, Oman Air, SpiceJet and Qatar Airways. Though night operations were not permitted till recently, the military now allows civil airlines to fly during the night. A greenfield airport is under construction at Mopa in Pernem taluka.[101] It is expected to be completed by 2022.[102]

Road

Goa's public transport largely consists of privately operated buses linking the major towns to rural areas. Government-run buses, maintained by the Kadamba Transport Corporation, link major routes (like the Panaji–Margao route) and some remote parts of the state. The Corporation owns 15 bus stands, 4 depots and one Central workshop at Porvorim and a Head Office at Porvorim.[103] In large towns such as Panajiand Margao, intra-city buses operate. However, public transport in Goa is less developed, and residents depend heavily on their own transportation, usually motorised two-wheelers and small family cars.

Goa has four National Highways passing through it. NH-66 (ex NH-17) runs along India's west coast and links Goa to Mumbai in the north and Mangalore to the south. NH-4A running across the state connects the capital Panaji to Belgaum in east, linking Goa to cities in the Deccan. The NH-366 (ex NH-17A) connects NH-66 to Mormugao Port from Cortalim. The new NH-566 (ex NH-17B) is a four-lane highway connecting Mormugao Port to NH-66 at Verna via Dabolim Airport, primarily built to ease pressure on the NH-366 for traffic to Dabolim Airport and Vasco da Gama. NH-768 (ex NH-4A) links Panaji and Ponda to Belgaum and NH-4. Goa has a total of 224 km (139 mi) of national highways, 232 km (144 mi) of state highway and 815 kilometres (506 miles) of district highway. National Highways in Goa are among the narrowest in the country and will remain so for the foreseeable future, as the state government has received an exemption that allows narrow national highways. In Kerala, highways are 45 metres (148 feet) wide. In other states National Highways are grade separated highways 60 metres (200 feet) wide with a minimum of four lanes, as well as 6 or 8 lane access-controlled expressways.[104][105]

Hired forms of transport include unmetered taxis and, in urban areas, auto rickshaws. Another form of transportation in Goa is the motorcycle taxi, operated by drivers who are locally called "pilots". These vehicles transport a single pillion rider, at fares that are usually negotiated. Other than buses, "pilots" tend to be the cheapest mode of transport.[106] River crossings in Goa are serviced by flat-bottomed ferry boats, operated by the river navigation department.

Rail

Goa has two rail lines – one run by the South Western Railway and the other by the Konkan Railway. The line run by the South Western Railway was built during the colonial era linking the port town of Vasco da Gama, Goa with Belgaum, Hubli, Karnataka via Margao. The Konkan Railway line, which was built during the 1990s, runs parallel to the coast connecting major cities on the western coast.

Sea

The Mormugao Port Trust near the city of Vasco handles mineral ore, petroleum, coal, and international containers. Much of the shipments consist of minerals and ores from Goa's hinterland. Panaji, which is on the banks of the Mandovi, has a minor port, which used to handle passenger steamers between Goa and Mumbai till the late 1980s. There was also a short-lived catamaran service linking Mumbai and Panaji operated by Damania Shipping in the 1990s.

See also

- Konkan

- Outline of Goa

- Test Yourself Goa

- Portuguese Goa and Damaon

References

Citations

- "Indian Districts by Population, Sex Ratio, Literacy 2011 Census". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. p. 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "The Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act, 1987" (PDF). daman.nic.in. U.T. Administration of Daman and Diu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Henn, Alexander (2014). Hindu-Catholic Encounters in Goa: Religion, Colonialism, and Modernity. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780253013002. OCLC 890531126. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "The Supreme Court of India". Courts in federal countries : federalists or unitarists?. Kincaid, John, Aroney, Nicholas. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2017. p. 225. ISBN 9781487514662. OCLC 982378193.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Reports of the finance commissions of India: First Finance Commission to the Twelfth Finance Commission: the complete report. India. Finance Commission. Academic Foundation. 2005. p. 268. ISBN 978-81-7188-474-2.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Liberation of Goa". Government Polytechnic, Panaji. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- Pillarisetti, Jagan. "The Liberation of Goa: an Overview". The Liberation of Goa:1961. bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- "Goa". National Informatics Centre(NIC). Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- Sakshena, R.N. (June 2003). Goa: Into the Mainstream. p. 5. ISBN 9788170170051. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Indian Archaeological Society (2006). Purātattva, Issue 36. Indian Archaeological Society. p. 254.

- The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia : inter-disciplinary studies in archaeology, biological anthropology, linguistics and genetics. Petraglia, M. D. (Michael D.), Allchin, Bridget. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. 2007. p. 85. ISBN 9781402055621. OCLC 187951478.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chakravarty, Kalyan Kumar (1997). Indian rock art and its global context. Bednarik, Robert G., Indirā Gāndhī Rāshṭrīya Mānava Saṅgrahālaya. (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 9788120814646. OCLC 38936967.

- Chakravarty, Kalyan Kumar (1997). Indian rock art and its global context. Bednarik, Robert G., Indirā Gāndhī Rāshṭrīya Mānava Saṅgrahālaya. (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 9788120814646. OCLC 38936967.

- C. R. Srinivasan; K. V. Ramesh; S. Subramonia Iyer (2004). Śrī puṣpāñjali: Recent Researches in Prehistory, Protohistory, Art, Architecture, Numismatics, Iconography, and Epigraphy: Dr. C.R. Srinivasan commemoration volume, Volume 1. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. pp. 469 pages (see page4). ISBN 9788180900563.

- Sakhardande, Prajal. "7th National Conference on Marine Archaeology of Indian Ocean Countries: Session V". Heritage and history of Goa. NIO Goa. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 BC – 1352 AD. Ramesh Anant S. Dhume. pp. 355 pages (see pages 100–150).

- De Souza 1990, p. 9

- De Souza 1990, p. 10

- De Souza 1990, p. 11

- Dobbie, Aline (2006). India: The Elephant's Blessing. Melrose Press. pp. 253 pages (see page 220).

- Anant Kakba Priolkar (1961). The Goa Inquisition: Being a Quatercentenary Commemoration Study of the Inquisition in India. Bombay University Press. p. 3.

- "The day India freed Goa". 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Poddar, Prem (2 July 2008). Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures - Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748630271.

- Hiremath, K. G. (2003). Recent advances in environmental science. Discovery Pub. House. p. 401. ISBN 9788171416790. OCLC 56390521.

- "Weather Information for Goa". Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Climatological Information for Goa, India". Hong Kong Observatory. 15 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- "DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING, STATISTICS & EVALUATION" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2018.

- Rubinoff, Arthur G. (1 January 1998). The construction of a political community : integration and identity in Goa. Sage Publications. p. 18. OCLC 38918113.

- Rubinoff, Arthur G. (1 January 1998). The construction of a political community : integration and identity in Goa. Sage Publications. p. 19. OCLC 38918113.

- Odds stacked against Parrikar Archived 13 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Anil Sastry, The Hindu, 31 January 2005, verified 2 April 2005

- Banerjee, Sanjay (6 June 2007). "Congress set to rule Goa again". The Times of India. Times Internet Limited. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- "North Goa District website". northgoa.nic.in. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- "Congress Asks Why Is BJP Invited To Form Government in Goa". ndtv.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Supreme Court to hear Congress plea against Goa governor's invitation to BJP". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Goa's BJP-led government wins floor test with support from 22 legislators". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Wildlife Sanctuaries in Goa". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- "Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation". Archived from the original on 13 April 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- Mohan, Vibhor (16 September 2008). "Chandigarh's per capita income is highest in India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Economy of Goa Archived 29 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine, from goenkar.com Archived 2 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine verified 2 April 2005.

- "About Goa: Tourism, Industries, Economy, Growth & Geography Information". ibef.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "Goa not to have any more SEZs". The Times of India. 13 November 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- "Goa Budget 2017" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2018.

- "Goa Population Sex Ratio in Goa Literacy rate data". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Scheduled Casts & Scheduled Tribes Population". Census Department of India. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- Havik, Philip J.; Newitt, Malyn (2015). Creole Societies in the Portuguese Colonial Empire. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 9781443884631. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Walking the Tightrope" (PDF). equitabletourism.org. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Language – India, States and Union Territories" (PDF). Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General. pp. 13–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Commissioner Linguistic Minorities. "42nd report: July 2003 – June 2004". p. para 11.3. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Solving the Language Imbroglio". Navhind Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- "Census of India – DISTRIBUTION OF 10,000 PERSONS BY LANGUAGE". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- Thomaz, Luís Filipe F. R. (1 October 2016). "The Socio-Linguistic Paradox of Goa". Human and Social Studies. 5 (3): 15–38. doi:10.1515/hssr-2016-0021.

- "India's religions by numbers". The Hindu (published 26 August 2015). 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Henn, Alexander (2014). Hindu-Catholic encounters in Goa: religion, colonialism, and modernity. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253013002. OCLC 890531126.

- "Tourist Arrivals (Year Wise)". Department of Tourism, Government of Goa website. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Gethin Chamberlain (31 August 2013). "Why Goa is looking to go upmarket – and banish Brits and backpackers: As visitor numbers dip, the Indian state wants to rid itself of budget tourists – but its rubbish mountains and beach gangs are putting off the rich". The Observer, The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- National Geographic Society (22 January 2015). "Top 10 Nightlife Cities – National Geographic Travel". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- "20 idyllic beach getaways". CNN. 12 July 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Basilica of Bom Jesus, Old Goa | Goa Jesuits". goajesuits.in. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "Pilgrims flock to Goa to see Saint Francis Xavier remains". BBC News. bbc.co.uk. 22 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Administrator. "Department of Tourism, Government of Goa, India - Tourist Arrivals (Year Wise)". goatourism.gov.in. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Nehru Science Centre website. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- NIO website Archived 19 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "R A Mashelkar conferred Gomant Vibhushan award". The Times of India. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Goa's highest civilian award to Charles Correa". The Times of India. 19 December 2011.

- "The Fate of Fado". Mid-Day. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- "Tiatr folk drama of Goa". Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Smitha Venkateswaran (14 April 2007). "Konkan goes Tiatrical". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "17 States and Six Central Ministries to Showcase their Tableaux in Republic Day Parade – 2016". Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Kerala / Kochi News: A Konkani cinema from the youth Archived 10 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Hindu (17 April 2011). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Panaji Konkani Cinema – A Long Way to Go Archived 26 August 2012 at WebCite. Daijiworld.com. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Yahoo! Groups. Yahoo!. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Konkani Cinema Day – Some Reflections Archived 10 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Navhindtimes.in (23 April 2011). Retrieved 28 July 2013

- ANI (18 September 2014). "Goa becomes permanent venue for IFFI". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Dearcinema.com Archived 23 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Celebrating Konkani cinema |iGoa. Navhindtimes.in (26 April 2011). Retrieved 28 July 2013. Archived 28 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Konkani movie 'The Victim' hits screens on September 14 Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine" – Times of India. Articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com (12 September 2012). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Joseph Zuzarte (14 March 2013). "The Rise of Cashew Feni". goastreets.com. Goa Streets. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Sheetal Wadhwa Munshaw (July 2012). "A Date With Port". verveonline.com. Verve. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Ashiqa Salvan. "Wine and dine in Goa". thewineclub.in. The Wine Club. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Mankekar, Kamla (2004). Temples of Goa. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India. pp. 99 pages(see pages 1–17). ISBN 9788123011615.

- Kamat, Krishnanand. Konkanyali Kavikala. Panaji: Goa Konkani Akademi.

- "Doordarshan Goa – Welcome to Doordarsha Kendra, Panaji, Goa, India". doordarshangoa.gov.in. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Goa Radio Stations on FM and mediumwave". asiawaves.net. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Komparify.com. "Komparify allows you to find the best packs and recharge them. Why Komplify? Komparify". komparify.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Goa Newspapers and News Sites". w3newspapers.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Mills, James (Summer 2001). "Football in Goa: Sport, Politics and the Portuguese in India". Soccer & Society. 2 (2): 75–88. doi:10.1080/714004840. S2CID 143324581.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Goan football has little cause to look back". Goa Football Association. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- "Nehru stadium". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- "FIFA U-17 World Cup: Goa stadium handed over to FIFA". The Indian Express. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "[Goanet] Goa Govt. institutes award in memory of Dilip Sardesai". Mail-archive.com. 8 August 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "Goa to host Asian Beach Games in 2018". The Times of India. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "MEDICALEDUCATION CELL-GMC- BAMBOLIM GOA". gmcmec.gov.in. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "District-specific Literates and Literacy Rates, 2001". Education for all in India. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- Malkarnekar, Gauree (6 April 2009). "No Administrative head". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- "Cotarli land for IIT Goa gets Centre's approval". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Diploma institutes and courses". Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Goa airport requests shift in Navy's flying sorties to reduce rush". The Economic Times. 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "After a year, SC allows resuming construction of airport at Goa's Mopa". Live Mint. 16 January 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Goa's Mopa airport delayed by a year". The Indian Express. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Economic Survey 2011–2012" (PDF). Government of Goa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- Goa, Goa Breaking News Archived 4 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. DigitalGoa.com (31 August 2010). Retrieved 28 July 2013

- Highway authority projects hit road block in Kerala, Goa, Bengal Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Business Standard (11 March 2012). Retrieved 28 July 2013

- Abram, David (1 January 2004). The Rough Guide to Goa (5 ed.). Rough Guides. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84353-081-7. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

Sources

- de Souza, Teotonio R. (1989). Essays in Goan history. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-263-7. Retrieved 24 August 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Souza, Teotonio R. (1990). Goa Through the Ages: An economic history. Goa University publication. 2. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-259-0. Retrieved 25 August 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Andrada (undated). The Life of Dom John de Castro: The Fourth Vice Roy of India. Jacinto Freire de Andrada. Translated into English by Peter Wyche. (1664). Henry Herrington, New Exchange, London. Facsimile edition (1994) AES Reprint, New Delhi. ISBN 81-206-0900-X.

External links

- Government

- General information

- Goa Encyclopædia Britannica entry

- Goa at Curlie