Geography of Poland

Poland is a country in Central Europe[1] with an area of 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq. mi.), and mostly temperate climate.[2] with an area of 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq. mi.), and a temperate seasonal climate.[2] Situated on the North-Central European Plain, Poland's mostly flat terrain extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Carpathian Mountains in the south. However, within that large plain, diverse small landforms run in bands east to west.

| |

| Continent | Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | Central Europe |

| Coordinates | 52°00′N 20°00′E |

| Area | Ranked 69th |

| • Total | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi) |

| • Land | 96.93% |

| • Water | 3.07% |

| Coastline | 770 km (480 mi) |

| Borders | 3,582 km (2,226 mi) |

| Highest point | Rysy 2,499 meters (8,199 ft) |

| Lowest point | Raczki Elbląskie −1.8 meters (−6 ft) |

| Longest river | Vistula 1,047 km (651 mi) |

| Largest lake | Śniardwy 113.8 km2 (43.9 sq mi) |

| Climate | temperate climate |

| Terrain | swamps, level terrain, hills, mountains |

| Natural Resources | coal, sulfur, copper, natural gas, iron, zinc, lead, salt, arable land |

| Exclusive economic zone | 30,533 km2 (11,789 sq mi) |

| Maps of Poland | |

|---|---|

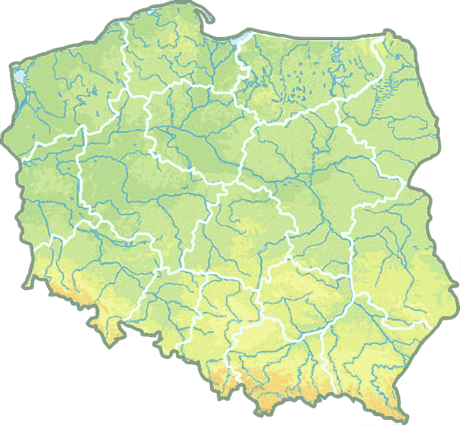

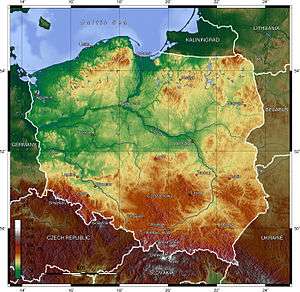

| Topography | |

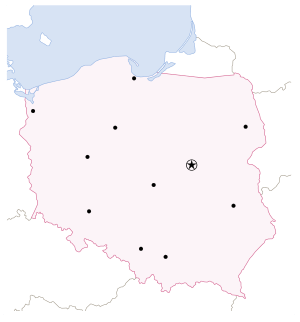

| Major agglomerations | |

Tatra

Sudetes

Interactive map with links to articles | |

| Provinces and highways | |

| |

| Satellite photo by NASA Landsat 7 | |

| |

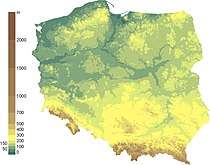

| Hypsometry | |

| |

| Satellite photo, winter 2003 | |

Snow cover in mid-winter |

The Baltic coast has two natural harbors, the larger one in the Gdańsk-Gdynia region, and a smaller one near Szczecin in the far northwest. The northeastern region, also known as the Masurian Lake District with more than 2,000 lakes,[3] is densely wooded and sparsely populated. To the south of the lake district, and across central Poland a vast region of plains extends all the way to the Sudetes on the Czech and Slovak borders southwest, and to the Carpathians on the Czech, Slovak and Ukrainian borders southeast. The central lowlands had been formed by glacial erosion in the Pleistocene ice age. The neighboring countries are Germany to the west, the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Ukraine and Belarus to the east, and Lithuania and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad to the northeast.

Topography

The country extends 876 kilometers from north to south and 689 kilometers from east to west. The total area is 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq mi) and includes inland waters. The average elevation is 173 meters, and only 3% of Polish territory, along the southern border, is higher than 500 meters. The highest elevation is Mount Rysy, which rises 2,499 meters in the Tatra Range of the Carpathian Mountains, 95 kilometers south of Kraków. About 63 square kilometers along the Gulf of Gdańsk are below sea level. It has an exclusive economic zone of 30,533 square kilometres (11,789 sq mi) within the Baltic Sea.[4]

Topographic regions

Poland is traditionally divided into five topographic zones from north to south.

The largest, the central lowlands or "Polish Plain" (Polish: Niż Polski or Nizina Polska), is narrow in the west, then expands to the north and south as it extends eastward. Along the eastern border, this zone reaches from the far northeast to within 200 kilometers of the southern border. The terrain in the central lowlands is quite flat, and earlier glacial lakes have been filled by sediment. The region is cut by several major rivers, including the Oder (Odra), which defines the Silesian Lowlands in the southwest, and the Vistula (Wisla), which defines the lowland areas of east-central Poland.

To the south of the lowlands are the lesser Poland uplands, a belt varying in width from 90 to 200 kilometers, formed by the gently sloping foothills of the Sudeten and Carpathian mountain ranges and the uplands that connect the ranges in southcentral Poland. The topography of this region is divided transversely into higher and lower elevations, reflecting its underlying geological structure. In the western section, the Silesia-Kraków Upthrust contains rich coal deposits.

The third topographic area is located on either side of Poland's southern border and is formed by the Sudeten and Carpathian ranges. Within Poland, neither of these ranges is forbidding enough to prevent substantial habitation; the Carpathians are especially densely populated. The rugged form of the Sudeten range derives from the geological shifts that formed the later Carpathian uplift. The highest elevation in the Sudeten is Śnieżka (1,602 meters) in the Karkonosze Mountains. The Carpathians in Poland, formed as a discrete topographical unit in the relatively recent Tertiary Era, are the highest mountains in the country. They are the northernmost edge of a much larger range that extends into the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary, and Romania. Within Poland the range includes two major basins, the Oświęcim and Sandomierz, which are rich in several minerals and natural gas.

To the north of the central lowlands, the lake region includes primeval forests - one of the last remaining in Europe and much of Poland's shrinking unspoiled natural habitat. Glacial action in this region formed lakes and low hills in the otherwise flat terrain adjacent to Lithuania and the Baltic Sea. Small lakes dot the entire northern half of Poland, and the glacial formations that characterize the lake region extend as much as 200 kilometers inland in western Poland. Wide river valleys divide the lake region into three parts. In the northwest, Pomerania is located south of the Baltic coastal region and north of the Warta and Noteć rivers. Masuria occupies the remainder of northern Poland and features a string of larger lakes. Most of Poland's 9,300 lakes that are more than 10,000 square metres in area are located in the northern part of the lake region, where they occupy about 10% of the surface area.

The Baltic coastal plains are a low-lying region formed of sediments deposited by the sea. The coastline was shaped by the action of the rising sea after the Scandinavian ice sheet retreated. The two major inlets in the smooth coast are the Pomeranian Bay on the German border in the far northwest and the Gulf of Gdańsk in the east. The Oder River empties into the former, and the Vistula forms a large delta at the head of the latter. Sandbars with large dunes form lagoons and coastal lakes along much of the coast.

Geology

The geological structure of Poland has been shaped by the continental collision of Europe and Africa over the past 60 million years on the one hand and the other by the Quaternary glaciations of northern Europe. Both processes shaped the Sudetes and the Carpathian Mountains. The moraine landscape of northern Poland contains soils made up mostly of sand or loam, while the ice age river valleys of the south often contain loess. The Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, the Pieniny, and the Western Tatras consist of limestone, while the High Tatras, the Beskids, and the Karkonosze are made up mainly of granite and basalts. The Polish Jura Chain is one of the oldest mountain ranges on earth.

Poland has 70 mountains over 2,000 metres (6,600 feet) in elevation, all in the Tatras. The Polish Tatras, which consist of the High Tatras and the Western Tatras, is the highest mountain group of Poland and of the entire Carpathian range. In the High Tatras lies Poland's highest point, the north-western summit of Rysy, 2,499 metres (8,199 ft) in elevation. At its foot lies the mountain lakes of Czarny Staw pod Rysami (Black Lake below Mount Rysy), and Morskie Oko (the Marine Eye).

The second highest mountain group in Poland is the Beskids, whose highest peak is Babia Góra, at 1,725 metres (5,659 ft). The next highest mountain groups is the Karkonosze in the Sudetes, whose highest point is Śnieżka, at 1,603 metres (5,259 ft); Śnieżnik Mountains whose highest point is Śnieżnik, at 1,425 metres (4,675 ft).

Tourists also frequent the Bieszczady Mountains in the far southeast of Poland, whose highest point in Poland is Tarnica, with an elevation of 1,346 metres (4,416 ft), Gorce Mountains in Gorce National Park, whose highest point is Turbacz, with elevations 1,310 metres (4,298 ft), and the Pieniny National Park in the Pieniny Mountains, whose highest point is Trzy Korony with elevations of 982 metres (3,222 ft) (the highest mountain of this range, Wysokie Skałki (Wysoka), with elevations 1,050 metres (3,445 ft), is located outside of the national park). The lowest point in Poland – at 2 metres (6.6 ft) below sea level – is at Raczki Elbląskie, near Elbląg in the Vistula Delta.

The only desert located in Poland stretches over the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie (the Coal Fields of Dąbrowa) region. It is called the Błędów Desert, located in the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland. It has a total area of 32 square kilometres (12 sq mi). It is one of only five natural deserts in Europe. But also, it is the warmest desert that appears at this latitude. Błędów Desert was created thousands of years ago by a melting glacier. The specific geological structure has been of big importance. The average thickness of the sand layer is about 40 metres (131 ft), with a maximum of 70 metres (230 ft), which made the fast and deep drainage very easy.

The Baltic Sea activity in Słowiński National Park created sand dunes which in the course of time separated the bay from the sea. As waves and wind carry sand inland the dunes slowly move, at a speed of 3 to 10 metres (9.8 to 32.8 ft) meters per year. Some dunes are quite high – up to 30 metres (98 ft). The highest peak of the park – Rowokol (115 metres or 377 feet above sea level) — is also an excellent observation point.

Land use

Poland is the fourth most forested country in Europe. Forests cover about 30.5% of Poland's land area based on international standards.[5] Its overall percentage is still increasing. Forests of Poland are managed by the National Program of Reforestation (KPZL), aiming an increase of forest-coverage to 33% in 2050. The richness of Polish forests (per SoEF 2011 statistics) is more than twice as high as the European average (with German and French forests being at the top), containing 2.304 billion cubic metres of trees.[5] The largest forest complex in Poland is Lower Silesian Wilderness.

More than 1% of Poland's territory, 3,145 square kilometres (1,214 sq mi), is protected within 23 Polish national parks. Three more national parks are projected for Masuria, the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, and the eastern Beskids. In addition, wetlands along lakes and rivers in central Poland are legally protected, as are coastal areas in the north. There are over 120 areas designated as landscape parks, along with numerous nature reserves and other protected areas (e.g. Natura 2000).

Present-day Poland is a country with favorable agricultural prospects, and over two million private farms. It is the leading producer of potatoes and rye in Europe,[6] the world's largest producer of triticale,[7] and one of the more important producers of barley, oats, sugar beets, flax, and various fruits.[6] It is also the European Union's fourth largest supplier of pig meat after Germany, Spain and France.[8]

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Poland belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of Poland belongs to three Palearctic Ecoregions of the continental forest spanning Central and Northern European temperate broadleaf and mixed forest ecoregions as well as the Carpathian montane conifer forest.

Many animals that have since died out in other parts of Europe still survive in Poland, such as the wisent in the ancient woodland of the Białowieża Forest and in Podlaskie. Other such species include the brown bear in Białowieża, in the Tatras, and in the Beskids, the gray wolf and the Eurasian lynx in various forests, the moose in northern Poland, and the beaver in Masuria, Pomerania, and Podlaskie.

In the forests, one also encounters game animals, such as red deer, roe deer and wild boars. In eastern Poland there are a number of ancient woodlands, like Białowieża forest, that have never been cleared by people. There are also large forested areas in the mountains, Masuria, Pomerania, Lubusz Land and Lower Silesia.

Poland is the most important breeding ground for a variety of European migratory birds.[10] Out of all of the migratory birds who come to Europe for the summer, one quarter of the global population of white storks (40,000 breeding pairs) live in Poland,[11] particularly in the lake districts and the wetlands along the Biebrza, the Narew, and the Warta, which are part of nature reserves or national parks.

Hydrology

The longest rivers are the Vistula (Polish: Wisła), 1,047 kilometres (651 mi) long; the Oder (Polish: Odra) which forms part of Poland's western border, 854 kilometres (531 mi) long; its tributary, the Warta, 808 kilometres (502 mi) long; and the Bug, a tributary of the Vistula, 772 kilometres (480 mi) long. The Vistula and the Oder flow into the Baltic Sea, as do numerous smaller rivers in Pomerania.

The Łyna and the Angrapa flow by way of the Pregolya to the Baltic, and the Czarna Hańcza flows into the Baltic through the Neman. While the great majority of Poland's rivers drain into the Baltic Sea, Poland's Beskids are the source of some of the upper tributaries of the Orava, which flows via the Váh and the Danube to the Black Sea. The eastern Beskids are also the source of some streams that drain through the Dniester to the Black Sea.

Poland's rivers have been used since early times for navigation. The Vikings, for example, traveled up the Vistula and the Oder in their longships. In the Middle Ages and in early modern times, when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was the breadbasket of Europe;[12] the shipment of grain and other agricultural products down the Vistula toward Gdańsk and onward to other parts of Europe took on great importance.[12]

With almost ten thousand closed bodies of water covering more than 1 hectare (2.47 acres) each, Poland has one of the highest numbers of lakes in the world. In Europe, only Finland has a greater density of lakes.[13] The largest lakes, covering more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), are Lake Śniardwy and Lake Mamry in Masuria, and Lake Łebsko and Lake Drawsko in Pomerania.

In addition to the lake districts in the north (in Masuria, Pomerania, Kashubia, Lubuskie, and Greater Poland), there is also a large number of mountain lakes in the Tatras, of which the Morskie Oko is the largest in area. The lake with the greatest depth—of more than 100 metres (328 ft)—is Lake Hańcza in the Wigry Lake District, east of Masuria in Podlaskie Voivodeship.

Among the first lakes whose shores were settled are those in the Greater Polish Lake District. The stilt house settlement of Biskupin, occupied by more than one thousand residents, was founded before the 7th century BC by people of the Lusatian culture.

Lakes have always played an important role in Polish history and continue to be of great importance to today's modern Polish society. The ancestors of today's Poles, the Polanie, built their first fortresses on islands in these lakes. The legendary Prince Popiel ruled from Kruszwica tower erected on the Lake Gopło.[14] The first historically documented ruler of Poland, Duke Mieszko I, had his palace on an island in the Warta River in Poznań. Nowadays the Polish lakes provide a location for the pursuit of water sports such as yachting and wind-surfing.

The Polish Baltic coast is approximately 528 kilometres (328 mi) long and extends from Świnoujście on the islands of Usedom and Wolin in the west to Krynica Morska on the Vistula Spit in the east. For the most part, Poland has a smooth coastline, which has been shaped by the continual movement of sand by currents and winds. This continual erosion and deposition has formed cliffs, dunes, and spits, many of which have migrated landwards to close off former lagoons, such as Łebsko Lake in Słowiński National Park.

Prior to the end of the Second World War and subsequent change in national borders, Poland had only a very small coastline; this was situated at the end of the 'Polish Corridor', the only internationally recognised Polish territory which afforded the country access to the sea. However, after World War II, the redrawing of Poland's borders and resulting 'shift' of the country's borders left it with a greatly expanded coastline, thus allowing for far greater access to the sea than was ever previously possible. The significance of this event, and importance of it to Poland's future as a major industrialised nation, was alluded to by the 1945 Wedding to the Sea.

The largest spits are Hel Peninsula and the Vistula Spit. The largest Polish Baltic island is Wolin. The largest sea harbours are Szczecin, Świnoujście, Gdańsk, Gdynia, Police and Kołobrzeg. The main coastal resorts are Świnoujście, Międzyzdroje (Misdroy), Kołobrzeg, Łeba, Sopot, Władysławowo and the Hel Peninsula.

Drainage

Nearly all of Poland is swirled northward into the Baltic Sea by the Vistula, the Oder, and the tributaries of these two major rivers. About half the country is drained by the Vistula, which originates in the Silesian Beskids in far south-central Poland.

The Vistula Basin includes most of the eastern half of the country and is drained by a system of rivers that mainly join the Vistula from the east. One of the tributaries, the Bug, defines 280 kilometers of Poland's eastern border with Ukraine and Belarus.

The Oder and its major tributary, the Warta, and a few smaller rivers as Kłodnica, Mała Panew, Bóbr, Lusatian Neisse (Nysa Łużycka) and Ina, form a basin that drains the western third of Poland into the Bay of Szczecin. The drainage effect on a large part of Polish terrain is weak, however, especially in the lake region and the inland areas to its south. The predominance of swampland, level terrain, and small, shallow lakes hinders large-scale movement of water. The rivers have two high-water periods per year. The first is caused by melting snow and ice dams in spring adding to the volume of lowland rivers; the second is caused by heavy rains in July.

Climate

.jpg)

Poland's long-term and short-term weather patterns are made transitional and variable by the collision of diverse air masses above the country's surface. Maritime air moves across Western Europe, Arctic air sweeps down from the North Atlantic Ocean, and subtropical air arrives from the South Atlantic Ocean. Although the Polar air dominates for much of the year, its conjunction with warmer currents generally moderates temperatures and generates considerable precipitation, clouds, and fog. When the moderating influences are lacking, winter temperatures in mountain valleys may drop to a minimum of −20 °C (−4 °F).

The spring arrives slowly in March or April, bringing mainly sunny days after a period of alternating wintertime and springtime conditions. Summer, which extends from June to August, is generally less humid than winter. Showers and thunderstorms alternate with dry sunny weather that is generated when southern and eastern winds prevail. Early autumn is generally sunny and warm before a period of rainy, colder weather in November begins the transition into winter. Winter, which may last from one to three months, brings frequent snowstorms but relatively low total precipitation.

The range of mean temperatures is 6 °C (42.8 °F) in the northeast to 10 °C (50 °F) in the southwest, but individual readings in Poland's regions vary widely by season. On the highest mountain peaks, the mean temperature is below 0 °C (32 °F). The Baltic coast, influenced by moderating west winds, mostly in Świnoujście, Międzyzdroje, Dziwnów, Nowe Warpno, Police and Szczecin, has cooler summers and warmer winters. The other temperature extreme is in the southeast along the border with Ukraine, where the greatest seasonal differences occur and winter temperatures average 4.5 °C below those in western Poland. The hottest cities in Poland are Tarnów, Wrocław and Słubice.

The average temperatures are rising,[17] however. In the period of 1980 to 2010, there were 19 Decembers without snow, and in the period of 2000 to 2010 seven. December 2006 was the warmest one in Poland since 1779. In most of Poland, average temperatures rose by 3-5 degrees Celsius during the last three decades.[18]

The average annual precipitation for the whole country is 600 mm (23.6 in), but isolated mountain areas receive as much as 1,300 mm (51.2 in) per year. The total is slightly higher in the southern uplands than in the central plains. A few areas, notably along the Vistula between Warsaw and the Baltic Sea and in the far northwest, average less than 500 mm (19.7 in). In winter about half the precipitation in the lowlands and the entire amount in the mountains falls as snow. On average, precipitation in summer is twice of that in winter, providing a dependable supply of water for crops. The growing season is about 40 days longer in the southwest than in the northeast, where spring arrives latest.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political geography

Poland's current voivodeships (provinces) are largely based on the country's historic regions, whereas those of the past two decades (to 1998) had been centred on and named for individual cities. The new units range in area from less than 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) for Opole Voivodeship to more than 35,000 square kilometres (14,000 sq mi) for Masovian Voivodeship. Administrative authority at voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed voivode (governor), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and an executive elected by that assembly.

The voivodeships are subdivided into powiats (often referred to in English as counties), and these are further divided into gminas (also known as communes or municipalities). Major cities normally have the status of both gmina and powiat. Poland has 16 voivodeships, 379 powiats (including 65 cities with powiat status), and 2,478 gminas.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Historical regions of the current Polish state

Within Poland's modern borders are the following historic regions:

- Greater Poland (Polish: Wielkopolska, Latin: Polonia Maior)

- Lesser Poland (Polish: Małopolska, Latin: Polonia Minor)

- Red Ruthenia (Polish: Ruś Czerwona, Latin: Ruthenia Rubra, only partially in modern Poland)

- Prussia (Polish: Prusy, German: Preußen, Latin: Borussia, only partially in modern Poland, also a German historical region)

- Lithuania Minor (Polish: Litwa Mniejsza, Latin: Lithuania Minor), only part in Poland, also a Lithuanian land and German historical region now mostly within the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia

- Masovia (Polish: Mazowsze, Latin: Mazovia)

- Kuyavia (Polish: Kujawy, Latin: Cuiavia)

- Lusatia (Polish: Łużyce, German: Lausitz, Latin: Lusatia, only partially in modern Poland, also a German historical region)

- Podlaskie (Polish: Podlasie, Polish: Podlaskie, Latin: Podlachia)

- Southern Podlasie (Polish: Podlasie Południowe)

- Pomerania (Polish: Pomorze, German: Pommern, Latin: Pomerania, only partially in modern Poland, also a German historical region)

- Pomerelia (Polish: Pomorze Gdańskie, German: Pommerellen, Latin: Pomerania)

- Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Silesian: Ślůnsk, German: Schlesien, Czech: Slezsko, Latin: Silesia), only part in Poland, also a Czech land and German historical region

Position in Europe

Linguistically, Poland may be placed in Eastern Europe because the official and most widely spoken language of the state is Polish – one of the West Slavic languages generally associated with the eastern section of the continent.[19] Using historical and cultural criteria, Poland can be identified as Western Europe as well, due to customs and cuisine it used to share with Italy,[20] and France.[21][22] For instance, Queen Bona Sforza revolutionized Polish eating habits after 1518 with unknown vegetables, fruits and legumes which became Poland's staples for centuries to come.[20] Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga introduced French specialties and brought with her scores of craftsmen, cooks and pâté makers along with table customs considered innately Polish today.[21][22] Poland shares customs and cuisine with present-day Belarus and Ukraine also,[23] much of it stemming from their common heritage as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[24] Multiple supranational organizations of significance categorize Poland as an Eastern European country for statistical purposes, including the Statistics Division of the United Nations[25] and EuroVoc (the multilingual thesaurus) of the European Union.[26] Several other agencies of the UN also place Poland in Eastern Europe.[27][28][29] Another common definition identifies the former Eastern Bloc territories as Eastern European states, thus including Poland.[30] However, critics of this categorization consider it outdated and detrimental to the reputation of the country.[31]

In contemporary times, Poland is leaning politically westwards – as a member of the EU[32] and NATO,[33] its government maintains generally close ties with Western Europe and the United States of America. Some argue that Eastern Europe is defined as a region with main characteristics consisting of Byzantine, Orthodox, and some Turco-Islamic influences. Although the Orthodox Ruthenians and Islamic Lipka Tatars together made up a large part of Poland's population throughout history, the Polish state and most ethnic Poles have embraced Catholicism;[34] as such, Poland is excluded from this category. Some scholars agree that Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic are Central European states due to their shared Habsburg heritage.[35] Economically, due to its membership in the Visegrád Group,[36] Poland is sometimes grouped together with the V4 states and Germany as part of Mitteleuropa (Central Europe).[37]

Statistics

- Area - comparative: slightly smaller than the US state of New Mexico.

- Land boundaries: total: 2,888 km (1,794 mi).

- Border countries and length: Belarus: 416 km (258 mi), Czech Republic: 790 km (490 mi), Germany: 467 km (290 mi), Lithuania: 103 km (64 mi), Russia (via Kaliningrad Oblast): 210 km (130 mi), Slovakia: 541 km (336 mi), and Ukraine: 528 km (328 mi)

- Coastline: 770 km (478 mi).

- Maritime claims: exclusive economic zone is 30,533 square kilometres (11,789 sq mi) and defined by international treaties.

- Territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

- Elevation extremes: lowest point Raczki Elbląskie -1.8 m (5 ft); highest point: Rysy 2,499 m (8,198 ft)

- Sea islands: Wolin, eastern part of Uznam (Usedom)

Resources and land use

- Natural resources: coal, sulfur, copper, natural gas, iron, zinc, lead, salt, arable land

- Land use: arable land: 47%; permanent crops: 15%; permanent pastures 13%

- Forests of Poland and woodlands: 29%; other: 10% (1993 est.)

- Irrigated land: 1,000 km.2 (1993 est.)

- Important rivers: Vistula (Wisła), Oder (Odra), Bug, Warta River, Narew, San

Environmental concerns

Natural hazards: Occasional flooding

National parks

Environment - current issues: The situation has improved since 1989 due to decline in heavy industry and increased environmental concern by postcommunist governments; air pollution nonetheless remains serious because of sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants, and the resulting acid rain has caused forest damage; water pollution from industrial and municipal sources is also a problem, as is disposal of hazardous wastes

Environment - international agreements:

party to: Air Pollution, Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Nuclear Test Ban, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Wetlands

signed, but not ratified: Air Pollution-Nitrogen Oxides, Air Pollution-Persistent Organic Pollutants, Air Pollution-Sulphur 1994, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol

Geography - note: historically, an area of conflict because of flat terrain and the lack of natural barriers on the North European Plain

See also

- Administrative division of Poland

- Borders of Poland

- Extreme points of Poland

- Tourism in Poland

- List of caves in Poland

- List of cities in Poland

- List of forests in Poland

- List of islands of Poland

- List of rivers of Poland

- List of mountains in Poland

- Poland A and B

References

- "Europe :: Poland — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland, 2008. Archived October 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Central Statistical Office (Poland). 28 July 2008.

- Masurian Lake District, at mazury.info.pl (in Polish)

- Inc., Advanced Solutions International. "404" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych (June 2012), Raport o stanie lasów w Polsce (Report on the Status of Forests in Poland) (PDF file, direct download 4.12 MB) (in Polish), Dyrekcja Generalna Lasów Państwowych (Main Directorate of State Forest), p. 8, retrieved 14 September 2013,

Określona według standardu międzynarodowego lesistość Polski na koniec roku 2011 wynosiła 30,5%.

- Glenn E. Curtis (1992). "Poland: A Country Study". Library of Congress Country Studies (GPO Country Studies Index, Washington).

- Gnel Gabrielyan, Domestic and Export Price Formation of U.S. Hops Archived April 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine School of Economic Sciences at Washington State University. PDF file, direct download 220 KB. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "Agriculture in the European Union. Statistical and Economic Information 2011" (PDF file, direct download 6.24 MB). World production and gross domestic production of main pigmeat-producing or exporting countries. European Union. Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. p. 307. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

EU: official slaughter only. Source: FAO.

- "Poland.pl – White Stork – About White Stork". Storks.poland.pl. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2011). "Kingdom of birds". Experience Poland » Geography » Environment » Fauna.

A real kingdom of birds is the Biebrza Basin, its wildlife making it one of the most unique areas in Poland. It is Europe's most valuable peatland/marshland and an important wildfowl breeding area on the continent, providing refuge for 263 bird species, including 185 nesting species.

- Kevin Hillstrom, Laurie Collier Hillstrom (2003). Europe: A Continental Overview of Environmental Issues, Volume 4. ABC-CLIO World geography. p. 34. ISBN 1-57607-686-5.

- Timothy Snyder (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999. Yale University Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-300-12841-X.

Commonwealth became the breadbasket of Western Europe, wrote Timothy Snyder, thanks to the presence of fertile southeastern regions of Podolia and east Galicia.

- Christine Zuchora-Walske (2013). "The Lakes Region". Poland. ABDO Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 1-61480-877-5.

Insert: Poland is home to 9,300 lakes. Finland is the only European nation with a higher density of lakes than Poland.

- Ḥayah Bar-Yitsḥaḳ (2001). Jewish Poland – legends of Origin: Ethnopoetics and Legendary Chronicles. Wayne State University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-8143-2789-3.

- TripAdvisor. "Top 10 Destinations – Poland". Travelers' Choice 2013 (Winners). TripAdvisor.ca The world largest travel site. pp. 1 of 10. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Wybrzeże Morza Bałtyckiego". www.zalewszczecinski.net (in Polish). Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- http://www.ekoedu.uw.edu.pl/rep/pdf/22fe31f808780c906db3ae3df0bb1728.pdf

- http://www.twojapogoda.pl/artykuly/113139,grudnie-coraz-mniej-sniezne-i-cieplejsze

- "American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages". AATSEEL. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Robert Strybel, Maria Strybel (2005). Polish Heritage Cookery. Hippocrene Books. pp. 11, 513. ISBN 0781811244. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Avigail (2013). "Francuskie wpływy kulinarne" [French culinary influences]. Encyklopedia Niam.pl, Internet Archive. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Katarzyna Urlewicz (2012). "Francuska służba królowej Ludwiki Marii Gonzagi" [French courtiers of Marie Louise Gonzaga in Poland]. Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie (Wilanów Palace Museum). Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Nigel Roberts (Apr 12, 2011), The Bradt Travel Guide 2, Belarus, page 81, (2nd), ISBN 1841623407.

- Based on 1618 population map Archived February 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (p.115), 1618 languages map (p.119), 1657–67 losses map (p.128) and 1717 map Archived February 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (p.141) from Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, Poland a Historical Atlas, Hippocrene Books, 1987, ISBN 0-88029-394-2.

- "UN Subdivision of Europe". UN Statistics Division. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "EuroVoc - subdivisions of Europe". EuroVoc. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "World Population Ageing 1950-2050" (PDF). Population Division, DESA, United Nations. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "UNAIDS Countries". UNAIDS, United Nations. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "UNICEF Eastern Europe". UNICEF, United Nations. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Hirsch, Donald; Kett, Joseph F.; Trefil, James S. (2002), The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 316, ISBN 0-618-22647-8,

Eastern Bloc. The name applied to the former communist states of eastern Europe, including Yugoslavia and Albania, as well as the countries of the Warsaw Pact

- Steven Cassedy. "Regions and Eastern Europe Regionalism". Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "EU 2004 Enlargement". Europa.eu. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Frank Schimmelfennig. "NATO's Enlargement to the East" (PDF). Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2012). Rocznik statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 2012 (PDF). Warszawa: Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych. (in Polish and English)

- "Definitions of regions in Europe". Global Perspectives. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Visegrád Group". Visegrád Group. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Bischof et al. (2000) p.558