Geography of Portugal

Portugal is a coastal nation in southwestern Europe, located at the western end of the Iberian Peninsula, bordering Spain (on its northern and eastern frontiers: a total of 1,214 kilometres (754 mi)). The Portuguese territory also includes a series of archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean (the Açores and Madeira), which are strategic islands along the North Atlantic. The extreme south is not too far from the Strait of Gibraltar, leading to the Mediterranean Sea. In total, the country occupies an area of 92,090 square kilometres (35,560 sq mi) of which 91,470 square kilometres (35,320 sq mi) is land and 620 square kilometres (240 sq mi) water.[1]

| |

| Continent | Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | Iberian Peninsula, Southern Europe |

| Coordinates | |

| Area | Ranked 109th |

| • Total | 92,391 km2 (35,672 sq mi) |

| • Land | 99.55% |

| • Water | †% |

| Coastline | 1,794 km (1,115 mi) |

| Borders | Total land borders: Portugal-Spain border (1214 km) |

| Highest point | Mount Pico 2351 m |

| Lowest point | Sea level (Atlantic Ocean |

| Longest river | Tagus (275 km within Portugal) |

| Largest lake | Lake Alqueva |

| Exclusive economic zone | 1,727,408 km2 (666,956 sq mi) |

Despite these definitions, the Portugal-Spain border remains an unresolved territorial dispute between the two countries. Portugal does not recognise the border between Caia and Ribeira de Cuncos River deltas, since the beginning of the 1801 occupation of Olivenza by Spain. This territory, though under de facto Spanish occupation, remains a de jure part of Portugal, consequently no border is henceforth recognised in this area.

Physical

Portugal is located on the western coast of the Iberian Peninsula and plateau, that divides the inland Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. It is located on the Atlantic coast of this plateau and crossed by several rivers which have their origin in Spain. Most of these rivers flow from east to west disgorging in the Atlantic; from north to south, the primary rivers are the Minho, Douro, Mondego, Tagus and the Guadiana.[2]

Coastline

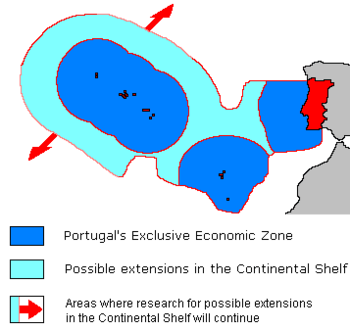

The continental shelf has an area of 28,000 square kilometres (11,000 sq mi), although its width is variable from 150 kilometres (93 mi) in the north to 25 kilometres (16 mi) in the south.[2] Its strong relief is marked by deep submarine canyons and the continuation of the main rivers. The Estremadura Spur separates the Iberian Abyssal and Tagus Abyssal Plains, while the continental slope is flanked by sea-mounts and abuts against the prominent Gorringe Bank in the south.[2] Currently, the Portuguese government claims a 200-metre (660 ft) depth, or to a depth of exploitation.

The Portuguese coast is extensive; in addition to approximately 943 kilometres (586 mi) along the coast of continental Portugal, the archipelagos of the Azores (667 km) and Madeira (250 km) are primarily surrounded by rough cliff coastlines. Most of these landscapes alternate between rough cliffs and fine sand beaches; the region of the Algarve is recognized for its sandy beaches popular with tourists, while at the same time its steep coastlines around Cape St. Vincent is well known for steep and forbidding cliffs. An interesting feature of the Portuguese coast is Ria Formosa with some sandy islands and a mild and pleasant climate characterized by warm but not very hot summers and generally mild winters.

Alternatively, the Ria de Aveiro coast (near Aveiro, referred to as "The Portuguese Venice"), is formed by a delta (approximately 45 kilometres (28 mi) length and a maximum 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) width) rich in fish and seabirds. Four main channels flow through several islands and islets at the mouth of the Vouga, Antuã, Boco, and Fontão Rivers. Since the 16th century, this formation of narrow headlands formed a lagoon, that, due to its characteristics allowed the formation and production of salt. It was also recognized by the Romans, whose forces exported its salt to Rome (then seen as a precious resource).

The Azores are also sprinkled with both alternating black sand and boulder-lined beaches, with only a rare exception, is there white sand beach (such as on the island of Santa Maria in Almagreira. The island of Porto Santo is one of the few extensive dune beaches in Portugal, located in the archipelago of Madeira.

Tidal gauges along the Portuguese coast have identified a 1–1.5 millimetres (0.039–0.059 in) rise in sea levels, causing large estuaries and inland deltas in some major rivers to overflow.[2]

As a result of its maritime possessions and long coastline, Portugal has an Exclusive Economic Zone of 1,727,408 km2 (666,956 sq mi). This is the 3rd largest EEZ of all countries in the European Union and the 20th in the world. The sea-zone, over which Portugal exercises special territorial rights over the economic exploration and use of marine resources encircles an area of 1,727,408 square kilometres (666,956 sq mi) (divided as: Continental Portugal 327,667 km2, Azores Islands 953,633 km2, Madeira Islands 446,108 km2).

Continent

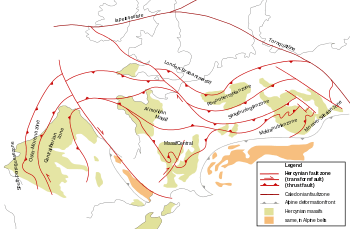

The Portuguese territory came into existence during the history of Gondwana and became aligned with European landforms after the super-continent Pangea began its slow separation into several smaller plates. The Iberian plate was formed during the Cadomian Orogeny of the late Neoproterozoic (about 650-550 Ma), from the margins of the Gondwana continent. Through collisions and accretion a group of island arcs (that included the Central Iberian Plate, Ossa-Morena Plate, South Portuguese Plate) began to disintegrate from Gondwana (along with other European fragments). These plates never separated substantially from each other since this period.[3] By the Mesozoic, the three "Portuguese plates" were a part of the Northern France Armoric Plate until the Bay of Biscay began to separate. Following the separation of the Iberian Abyssal Plain, Iberia and Europe began to drift progressively from North America, as the Mid-Atlantic fracture zone pulled the three plates away from the larger continent. Eventually, Iberia collided with southern France attaching the region into a peninsula of Europe (during the Cenozoic). Since the late Oligocene, the Iberian plate has been moving as part of the Eurasian plate, with the boundary between Eurasia and Africa situated along the Azores–Gibraltar fracture zone.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

The Iberian peninsula, defined by is coastline, is due to a fragment of the Variscan tectonic fracture zone, the Iberian-Hesperian Massif, which occupies the west-central part of the plateau.[2] This formation is crossed by the Central System, along an east-northeast to west-southwest alignment, parallel to the European Baetic Chain (an aspect of the Alpine Chain).[2] The Central Cordillera is itself divided into two blocks, while three main river systems drain the differing geomorphological terrains:[2]

- the Northern Meseta (with a mean altitude of 800 metres (2,600 ft)) is drained by the Douro River (running east to west);

- the Southern Meseta (within a range of 200 to 900 metres (660 to 2,950 ft) altitude) is drained by the Tagus River (running east to west) from Spain, and the Guadiana River (running north to south), comprising the Lower Tagus and Sado Basins.

To the north the landscape is mountainous in the interior areas with plateaus, cut by four breakings lines that allow the development of more fertile agricultural areas.

The south down as far as the Algarve features mostly rolling plains with a climate somewhat warmer and drier than the cooler and rainier north. Other major rivers include the Douro, the Minho and the Guadiana, similar to the Tagus in that all originate in Spain. Another important river, the Mondego, originates in the Serra da Estrela (the highest mountains in mainland Portugal at 1,993 m).

No large natural lakes exist in Continental Portugal, and the largest inland water surfaces are dam-originated reservoirs, such as the Alqueva Reservoir with 250 square kilometres (97 sq mi), the largest in Europe. However, there are several small freshwater lakes in Portugal, the most notable of which are located in Serra da Estrela, Lake Comprida (Lagoa Comprida) and Lake Escura (Lagoa Escura), which were formed from ancient glaciers. Pateira de Fermentelos is a small natural lake near Aveiro one the largest natural lake in the Iberian Peninsula and with rich wildlife. In the Azores archipelago lakes were formed in the caldera of extinct volcanoes. Lagoa do Fogo and Lagoa das Sete Cidades (two small lakes connected by a narrow way) are the most famous lakes in São Miguel Island.

Lagoons in the shores of the Atlantic exist. For instance, the Albufeira Lagoon and Óbidos Lagoon (near Foz do Arelho, Óbidos).

Archipelagos

In addition to continental Europe, Portugal consists of two Autonomous Regions in the Atlantic Ocean, consisting of the archipelagos of Madeira and Azores. Madeira is located on the African Tectonic Plate, and comprises the main island of Madeira, Porto Santo and the smaller Savage Islands. The Azores, which are located between the junction of the African, European and North American Plates, straddle the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. There are nine islands in this archipelago, usually divided into three groups (Western, Central and Eastern) and several smaller Formigas (rock outcroppings) located between São Miguel and Santa Maria Islands. Both island groups are volcanic in nature, with historic volcanology and seismic activity persisting to the present time. In addition, there are several submarine volcanos in the Azores (such as Dom João de Castro Bank), that have erupted historically (such as the Serrata eruption off the coast of Terceira Island). The last major volcanic event occurred in 1957-58 along the western coast of Faial Island, which formed the Capelinhos Volcano. Seismic events are common in the Azores. The Azores are occasionally subject to very strong earthquakes, as is the continental coast. Wildfires occur mostly in the summer in mainland Portugal and extreme weather in the form of strong winds and floods also occurs mainly in winter. The Azores are occasionally stricken by tropical cyclones such as Hurricane Jeanne (1998) and Hurricane Gordon (2006).

Climate

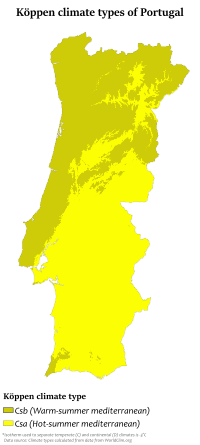

Most of Portugal has a warm Mediterranean climate according to the Köppen climate classification: Csa in most of the lands south of the Tagus River, inland Douro Valley in the North and Madeira Islands. The Csb pattern can be found north of that river, Costa Vicentina in coastal Southern Portugal, and the eastern group of the Azores islands. Most of the Azores have an Oceanic climate or Cfb, while a small region in inland Alentejo has Bsk or semi-arid climate. The Savage Islands, that belong to the Madeira archipelago, also have an arid climate. The sea surface temperatures in these archipelagos vary from 16–18 °C (60.8–64.4 °F) in winter to 23–24 °C (73.4–75.2 °F) in the summer, occasionally reaching 26 °C (78.8 °F).

The annual average temperature in mainland Portugal varies from 12–13 °C (53.6–55.4 °F) in the mountainous interior north to 17–18 °C (62.6–64.4 °F) in the south (in general the south is warmer and drier than the north). The Madeira and Azores archipelagos have a narrower temperature range. Extreme temperatures occur in the mountains in the interior North and Centre of the country in winter, where they may fall below −10 °C (14 °F) or in rare occasions below −20 °C (−4 °F), particularly in the higher peaks of Serra da Estrela, and in southeastern parts in the summer, sometimes exceeding 45 °C (113 °F). The official absolute extreme temperatures are −16 °C (3.2 °F) in Penhas da Saúde on 4 February 1954 and Miranda do Douro, and 47.4 °C (117.3 °F) in Amareleja in the Alentejo region, on 1 August 2003.[14] There are, however, unofficial records of 50.5 °C (122.9 °F) on 4 August 1881 in Riodades, São João da Pesqueira.[15] Such temperatures are not validated since these were measured in enclosures that were much more susceptible to solar radiation and/or in enclosed gardens which tend to heat up a lot more than in the open where temperatures should be measured. There are also records of -17,5 °C (0,5 °F) from a Polytechnic Institute in Bragança, and below −20 °C (−4.0 °F) in Serra da Estrela, which have no official value since they were not recorded by IPMA. Such values are however perpetuated by weather enthusiasts who are fond of extremes. The annual average rainfall varies from a bit more than 3,000 mm (118.1 in) in the mountains in the north to less than 500 mm (19.7 in) in southern parts of Alentejo. Portugal as a whole is amongst the sunniest areas in Europe, with around 2300–3200 hours of sunshine a year, an average of 4-6h in winter and 10-12h in the summer. The sea surface temperature is higher in the south coast where it varies from 15–16 °C (59.0–60.8 °F) in January to 22–23 °C (71.6–73.4 °F) in August, occasionally reaching 25 °C (77 °F); on the west coast the sea surface temperature is around 14–15 °C (57.2–59.0 °F) in winter and 18–20 °C (64–68 °F) in the summer.

Seasons in Portugal

| Seasons | Meteorological | Astronomical | real feel |

|---|---|---|---|

| spring | 1 March to 31 May | 21 March to 20 June | March to May |

| summer | 1 June to 31 August | 21 June to 20 September | June to September |

| autumn | 1 September to 30 November | 21 September to 20 December | October to November |

| winter | 1 December to 28/29 February | 21 December to 20 March | December to February |

Weather phenomena recorded in previous years in Portugal

| Events (average annual) | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain days | 16 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 12 |

| Snow days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hail days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thunderstorm days | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Fog days | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| Tornado days* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Day hours | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| Daily sunny hours | 8 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 6 |

*Tornados - counted for last 5 years [16]

Whole year UV Index table for Portugal [17]

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Environment

Environment - current issues: soil erosion; air pollution caused by industrial and vehicle emissions; water pollution, especially in coastal areas

Environment - international agreements:

party to:

Air Pollution, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Marine Life Conservation, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands

signed, but not ratified:

Air Pollution-Persistent Organic Pollutants, Air Pollution-Volatile Organic Compounds, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Environmental Modification, Nuclear Test Ban

Terrain: Mountainous and hilly north of the Tagus River, rolling plains in south

Elevation extremes:

lowest point:

Atlantic Ocean 0 m

highest point:

Ponta do Pico (Pico or Pico Alto) on Ilha do Pico in the Azores 2,351 m

Natural resources: fish, forests (cork), tungsten, iron ore, uranium ore, marble, arable land, hydroelectric power

Land use:

arable land:

26%

permanent crops:

9%

permanent pastures:

9%

forests and woodland:

36%

other:

20% (1993 est.)

Irrigated land: 6,300 km2 (1993 est.)

References

- "Portugal". CIA - The World Factbook. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- Eldridge M. Moores and Rhodes Whitmore Fairbridge (1997), p.612

- López-Guijarro et al. 2008.

- Srivastava et al.

- Le Pichon & Sibuet 1971.

- Le Pichon, Sibuet & Francheteau 1977.

- Sclater, Hellinger & Tapscott 1977.

- Grimaud, S.; Boillot, G.; Collette, B.J.; Mauffret, A.; Miles; P.R.; Roberts, D.B. (January 1982). "Western extension of the Iberian-European plate-boundary during early Cenozoic (Pyrenean) convergence: a new model". Marine Geology. 45 (1–2): 63–77. Bibcode:1982MGeol..45...63G. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(82)90180-3.

- JL Olivet; JM Auzende; P Beuzart (September 1983). "Western extension of the Iberian-European plate boundary during the Early Cenozoic (Pyrenean) convergence: A new model — Comment". Marine Geology. 53 (3): 237–238. Bibcode:1983MGeol..53..237O. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(83)90078-6.

- S. Grimaud; G. Boillot; B.J. Collette; A. Mauffret; P.R. Miles; D.B. Roberts (September 1983). "Western extension of the Iberian-European plate boundary during the Early Cenozoic (Pyrenean) convergence: A new model — Reply". Marine Geology. 53 (3): 238–239. Bibcode:1983MGeol..53..238G. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(83)90079-8.

- Olivet et al. 1984.

- Schouten, Srivastava & Klitgord 1984.

- Savostovin et al. 1986.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2018-12-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "World Weather Trivia Page". Archived from the original on 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- "The best time and weather to travel to Portugal . Travel weather and climate". hikersbay.com. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- http://www.ipma.pt. "IPMA - IUV Geo". www.ipma.pt. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

Sources

- Central Intelligence Agency, ed. (2010). "Portugal: CIA World Factbook". Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- Symington, Martin (2003). "Portugal". Eyewitness Travel Guide series. Dorling Kindersley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7894-9423-8.

- Moores, Eldridge M.; Fairbridge, Rhodes Whitmore, eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of European and Asian Regional Geology. London, England: Chapman & Hall. pp. 611–619. ISBN 9780412740404.

- Le Pichon, X.; Sibuet, J.C. (September 1971). "Western extension of boundary between European and Iberian plates during the Pyrenean orogeny" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 12 (1): 83–88. Bibcode:1971E&PSL..12...83L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.493.7034. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(71)90058-6.

- Olivet, Jean-Louis; Bonnin, J.; Beuzart, Paul; Auzende, Jean-Marie (1984). Cinématique de l'Atlantique Nord et Central [Kinematics of the North and Central Atlantic] (Report). Publications du C.N.E.X.O. Série "Rapports scientifiques et techniques". 54. Institut français de recherche pour l'exploitation de la mer. pp. 1–108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Pichon, X.; Sibuet, J. C.; Francheteau, J. (23 March 1977). "The fit of the continents around the North Atlantic Ocean". Tectonophysics. 38 (3–4): 169–209. Bibcode:1977Tectp..38..169L. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(77)90210-4.

- López-Guijarro, Rafael; Armendáriz, Maider; Quesada, Cecilio; Fernández-Suárez, Javier; Murphy, J. Brendan; Pin, Christian; Bellido, Felix (2008). "Ediacaran–Palaeozoic tectonic evolution of the Ossa Morena and Central Iberian zones (SW Iberia) as revealed by Sm–Nd isotope systematics" (PDF). Tectonophysics. Elsevier. 461 (1–4): 202–214. Bibcode:2008Tectp.461..202L. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2008.06.006. ISSN 0040-1951 – via ScienceDirect.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Savostovin, L. A.; Sibuet, J. C.; Zonenshain, L. P.; Le Pichon, X.; Roulet, M. J. (1986). "Kinematic evolution of the Tethys belt from the Atlantic ocean to the pamirs since the Triassic". Tectonophysics. 123 (1–4): 1–35. Bibcode:1986Tectp.123....1S. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(86)90192-7.

- Schouten H.; Srivastava S. P.; Klitgord, K. (1984). Trans. Am. Geophys. Union. 65: 190. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sclater, J. G.; Hellinger, S.; Tapscott, C. R. J. (1977). "Paleobathymetry Of Atlantic Ocean From Jurassic To Present". The Journal of Geology. 85 (5): 509–552. Bibcode:1977JG.....85..509S. doi:10.1086/628336. ISSN 0022-1376.

- Seber, D.; Barazangi, M.; Ibenbrahim, A.; Demnati, A. (1996). "Geophysical evidence for lithospheric delamination beneath the Alboran Sea and Rif--Betic mountains" (PDF). Nature. 379 (6568): 785–790. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..785S. doi:10.1038/379785a0.

- Srivastava, S.P.; Schouten, H.; Roest, W.R.; Klitgord, K.D.; Kovacs, L.C.; Verhoef, J.; Macnab, R. (19 April 1990). "Iberian Plate Kinematics: A Jumping Plate Boundary between Eurasia and Africa". Nature. 344 (6268): 756–759. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..756S. doi:10.1038/344756a0.

.png)