Geography of Norway

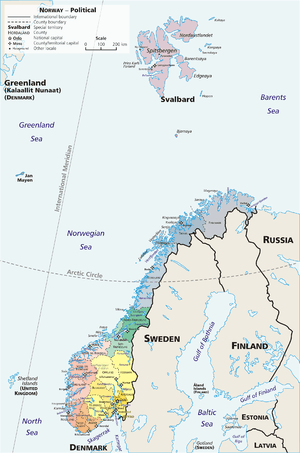

Norway is a country located in Northern Europe on the northern and western parts of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The majority of the country borders water, including the Skagerrak inlet to the south, the North Sea to the southwest, the North Atlantic Ocean (Norwegian Sea) to the west, and the Barents Sea to the north. It has a land border with Sweden to the east and a shorter border with Finland and an even shorter border with Russia to the northeast.

| |

| Continent | Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | Northern Europe |

| Coordinates | 50 degrees north and 8 degrees east |

| Area | |

| • Total | 385,170 km2 (148,710 sq mi) |

| • Land | 94.95% |

| • Water | 5.05% |

| Coastline | 25,148 km (15,626 mi) |

| Borders | Total land borders: 2515 km |

| Highest point | Galdhøpiggen 2,469 m |

| Lowest point | Norwegian Sea -0 meters |

| Longest river | Glomma 604 km |

| Largest lake | Mjøsa 362 km2 |

| Exclusive economic zone | Norway with Svalbard, Jan Mayen and Bouvet Island: 2,385,178 km2 (920,922 sq mi) |

Norway has an elongated shape, one of the longest and most rugged coastlines in the world, and some 50,000 islands off its much indented coastline. It is one of the world's northernmost countries, and it is one of Europe's most mountainous countries, with large areas dominated by the Scandinavian Mountains. The country's average elevation is 460 metres (1,510 ft), and 32 percent of the mainland is located above the tree line. Its country-length chain of peaks is geologically continuous with the mountains of Scotland, Ireland, and, after crossing under the Atlantic Ocean, the Appalachian Mountains of North America. Geologists hold that all these formed a single range prior to the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea.[1]

During the last glacial period, as well as in many earlier ice ages, virtually the entire country was covered with a thick ice sheet. The movement of the ice carved out deep valleys. As a result of the ice carving, Sognefjorden is the world's second deepest fjord and Hornindalsvatnet is the deepest lake in Europe. When the ice melted, the sea filled many of these valleys, creating Norway's famous fjords.[2] The glaciers in the higher mountain areas today are not remnants of the large ice sheet of the ice age—their origins are more recent.[3] The regional climate was up to 1–3 °C (1.8–5.4 °F) warmer in 7000 BC to 3000 BC in the Holocene climatic optimum, (relative to the 1961-90 period), melting the remaining glaciers in the mountains almost completely during that period.

Even though it has long since been released from the enormous weight of the ice, the land is still rebounding several millimeters a year. This rebound is greatest in the eastern part of the country and in the inner parts of the long fjords, where the ice cover was thickest. This is a slow process, and for thousands of years following the end of the ice age, the sea covered substantial areas of what is today dry land. This old seabed is now among the most productive agricultural lands in the country.

.jpg)

Statistics

Geographic coordinates: 62°N 10°E

Map references: Europe

Area:

total: 324,220 km2 (125,180 sq mi)

land: 307,860 km2 (118,870 sq mi)

water: 16,360 km2 (6,320 sq mi)

With Svalbard and Jan Mayen included: 385,199 km2 (148,726 sq mi)

Area - comparative:

The contiguous area is slightly smaller than Vietnam and slightly larger than the US state of New Mexico.

With Svalbard and Jan Mayen included, the area is slightly larger than Japan.

Land boundaries:

total: 2,515 km (1,563 mi)

border countries: Finland 729 km (453 mi); Sweden 1,619 km (1,006 mi); Russia 196 km (122 mi).

Coastline: continental 25,148 km (15,626 mi); including islands 83,281 km (51,748 mi) [4]

Maritime claims:

contiguous zone: 10 nmi (18.5 km; 11.5 mi)

continental shelf: 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi)

exclusive economic zone: 2,385,178 km2 (920,922 sq mi)

territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

Norway's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) totals 2,385,178 km2 (920,922 sq mi). It is one of the largest in Europe and the 17th largest in the world. The EEZ along the mainland makes up 878,575 km2 (339,220 sq mi), the Jan Mayen EEZ makes up 29,349 km2 (11,332 sq mi), and since 1977 Norway has claimed an economic zone around Svalbard of 803,993 km2 (310,423 sq mi).

Physical geography

Overview

Glaciated; mostly high plateaus and rugged mountains broken by fertile valleys; small, scattered plains; coastline deeply indented by fjords; arctic tundra only in the extreme northeast (largely found on the Varanger Peninsula). Frozen ground all-year can also be found in the higher mountain areas and in the interior of Finnmark county. Numerous glaciers are also found in Norway.

Elevation extremes:

Lowest point: Norwegian Sea 0 m

Highest point: Galdhøpiggen 2,469 metres (8,100 ft)

Mainland

Scandinavian Mountains: the Scandinavian Mountains are the most defining feature of the country. Starting with Setesdalsheiene north of the Skagerrak coast, the mountains are found in large parts of the country and intersect the many fjords of Vestlandet. This region includes Hardangervidda, Jotunheimen (with Galdhøpiggen at 2,469 metres (8,100 ft) a.s.l.), Sognefjell, and Trollheimen in the north, with large glaciers, such as Jostedalsbreen, Folgefonna, and Hardangerjøkulen. The mountain chain swings eastwards south of Trondheim, with ranges such as Dovrefjell and Rondane, and reaches the border with Sweden, where they have become mostly gently sloping plateaus. The mountains then follow the border in a northeasterly direction and are known as Kjølen (the "keel"). The mountains intersect many fjords in Nordland and Troms, where they become more alpine and create many islands after they meet the sea. The Scandinavian mountains form the Lyngen Alps, which reach into northwestern Finnmark, gradually becoming lower from Altafjord towards Nordkapp (North Cape), where they finally end at the Barents Sea.

The Scandinavian Mountains naturally divide the country into physical regions; valleys surround the mountains in all directions. The following physical regions will only partially correspond to traditional regions and counties in Norway.

Southern coast: the southern Skagerrak and North Sea coast is the lowland south of the mountain range, from Stavanger in the west to the western reaches of the outer part of the Oslofjord in the east. In this part of the country, valleys tend to follow a north–south direction. This area is mostly hilly, but with some very flat areas such as Lista and Jæren.

Southeast: the land east of the mountains (corresponding to Østlandet, most of Telemark, and Røros) is dominated by valleys running in a north–south direction in the eastern part, and in a more northwest–southeast direction further west, the valleys terminating at the Oslofjord. The longest valleys in the country are here—Østerdal and Gudbrandsdal. This region also contains large areas of lowland surrounding the Oslofjord, as well as the Glomma River and Lake Mjøsa.

Western fjords: the land west of the mountains (corresponding to Vestlandet north of Stavanger) is dominated by the mountain chain, as the mountains extend, gradually becoming lower, all the way to the coast. This region is dominated by large fjords, the largest being Sognefjord and Hardangerfjord. Geirangerfjord is often regarded as having the ultimate in fjord scenery. The coast is protected by a chain of skerries (small, uninhabited islands—the Skjærgård) that are parallel to the coast and provide the beginning of a protected passage for almost the entire 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) route from Stavanger to Nordkapp. In the south, fjords and most valleys generally run in a west–east direction, and, in the north, in a northwest–southeast direction.

Trondheim region: the land north of Dovre (corresponding to Trøndelag except Røros) comprises a more gentle landscape with more rounded shapes and mountains, and with valleys terminating at the Trondheimsfjord, where they open up onto a large lowland area. Further north is the valley of Namdalen, opening up in the Namsos area. However, the Fosen peninsula and the most northern coast (Leka) is dominated by higher mountains and narrower valleys.

Northern fjords: the land further north (corresponding to Nordland, Troms, and northwestern Finnmark) is again dominated by steep mountains going all the way to the coast and by numerous fjords. The fjords and valleys generally lie in a west–east direction in the southern part of this area, and a more northwest–southeast direction further north. The Saltfjellet mountain range is an exception, as the valley runs in a more north–south direction from these mountains. This long, narrow area includes many large islands, such as Lofoten, Vesterålen, and Senja.

Far northeast: the interior and the coast east of Nordkapp (corresponding to Finnmarksvidda and eastern Finnmark) is less dominated by mountains, and is mostly below 400 m (1,300 ft). The interior is dominated by the large Finnmarksvidda plateau. There are large, wide fjords running in a north–south direction. This coast lacks the small islands, or skerries, typical of the Norwegian coast. Furthest to the east, the Varangerfjord runs in an east–west direction and is the only large fjord in the country whose mouth is to the east.

Arctic islands

Svalbard: further north, in the Arctic ocean, lies the Svalbard archipelago, which is also dominated by mountains that are mostly covered by large glaciers, especially in the eastern part of the archipelago, where glaciers cover more than 90%, with one glacier, Austfonna, being the largest in Europe. Unlike on the mainland, these glaciers calve directly into the open ocean.

Jan Mayen: to the far northwest, halfway towards Greenland, is Jan Mayen island, where the only active volcano in Norway, Beerenberg, is found.

Antarctic islands and claim to Antarctica

Bouvet Island: located in the South Atlantic Ocean at 54°S and mostly covered by glaciers, this island is one of the most remote in the world, inhabited only by seals and birds.

Peter I Island: located in the South Pacific Ocean at 69°S and 90°W, this island is dominated by glaciers and a volcano. As with Bouvet Island, this island is regarded as an external dependency, and not part of the kingdom.

Queen Maud Land is Norway's claim in Antarctica. This large, sectorial area stretches to the South Pole and is completely dominated by the world's largest ice sheet, but with some impressive nunataks (bare rock) penetrating above the ice. The Troll Research Station manned by Norway is located on a snow-free mountain slope, the only station in Antarctica not to be located on the ice.

- Physical geography

Rafsundet in September, Northern Norway

Rafsundet in September, Northern Norway

Svalbard tundra

Svalbard tundra Beerenberg (2277 m) is the world's most northerly active volcano

Beerenberg (2277 m) is the world's most northerly active volcano

Sunlight, time zones, and tides

Areas in Norway located north of the Arctic Circle have extreme darkness in winter, which increases with latitude. At Longyearbyen on the Svalbard islands in the extreme north, the upper part of the sun's disc is above the horizon from 19 April to 23 August, and winter darkness lasts from 27 October to 14 February. The corresponding dates for still northerly Tromsø are 17 May – 25 July, and 26 November – 15 January. The winter darkness is not totally dark on the mainland, as there is twilight for a few hours around noon in Tromsø; but in Longyearbyen there is near total darkness in the midst of the dark period. Even the southern part of the country experiences large seasonal variations in daylight; in Oslo the sun rises at 03:54 and sets 22:54 at the summer solstice, but is only above the horizon from 09:18 - 15:12 at the winter solstice. The northern part of the country is located in the aurora borealis zone; the aurora is occasionally seen in the southern part of the country as well.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kristiansand sunrise & sunset 15. of the month | 09:04 - 16:12 | 08:00 - 17:25 | 06:45 - 18:30 | 06:18 - 20:40 | 05:03 - 21:45 | 04:23 - 22:34 | 04:47 - 22:20 | 05:49 - 21:15 | 06:56 - 19:50 | 08:02 - 18:24 | 08:14 - 16:10 | 09:08 - 15:37 | |

| Trondheim sunrise & sunset 15. of month | 09:38 - 15:18 | 08:12 - 16:55 | 06:38 - 18:18 | 05:51 - 20:48 | 04:13 - 22:19 | 03:04 - 23:34 | 03:41 - 23:05 | 05:12 - 21:31 | 06:41 - 19:45 | 08:05 - 18:02 | 08:39 - 15:26 | 09:55 - 14:32 | |

| Tromsø sunrise & sunset 15. of month | 11:37 - 12:10 | 08:17 - 15:42 | 06:08 - 17:40 | 04:45 - 20:47 | 01:46 - 23:45 | Midnight sun | Midnight sun | 03:42 - 21:51 | 05:55 - 19:22 | 07:53 - 17:05 | 09:23 - 13:33 | Polar night | |

| Source: Almanakk for Norge; University of Oslo, 2011. Note: Daylight saving in effect from last Sunday in March to last Sunday in October. In Tromsø, the sun is below the horizon until 15 January, but is blocked by mountains until 21 January. | |||||||||||||

Norway is on Central European Time, corresponding to the 15°E longitude. As the country is very elongated, this is at odds with the local daylight hours in the eastern and western parts. In Vardø local daylight hours are 64 minutes earlier, and in Bergen, they are 39 minutes later. Thus, Finnmark gains early morning daylight but loses evening daylight, and Vestlandet loses early morning light but gains more evening daylight in this time zone. Daylight saving time (GMT + 2) is observed from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October.

The difference between low tide and high tide is small on the southern coast and large in the north; ranging from on average 0.17 m in Mandal to about 0.30 m in Oslo and Stavanger, 0.90 m in Bergen, 1.80 m in Trondheim, Bodø and Hammerfest and as much as 2.17 m in Vadsø.

Climate

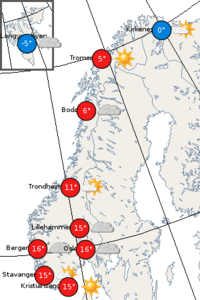

The climate of Norway is more temperate than could be expected for such high latitudes. This is mainly due to the North Atlantic Current with its extension, the Norwegian Current, raising the air temperature;[5] the prevailing southwesterlies bringing mild air onshore; and the general southwest–northeast orientation of the coast, which allows the westerlies to penetrate into the Arctic. The January average in Brønnøysund[6] is 14.6 °C (26.2 °F) warmer than the January average in Nome, Alaska,[7] even though both towns are situated on the west coast of the continents at 65°N. In July, the difference is reduced to 2.9 °C (5.2 °F). The January average of Yakutsk, in Siberia but slightly further south, is 42.2 °C (76.0 °F) colder than in Brønnøysund.[8]

Precipitation

Some areas of Vestlandet and southern Nordland are Europe's wettest, due to orographic lift, particularly where the westerlies are first intercepted by high mountains. This occurs slightly inland from the outer skerry guard. Brekke in Sogn og Fjordane has the highest annual precipitation with 3,575 mm (140.7 in). Annual precipitation can exceed 5,000 mm (196.9 in) in mountain areas near the coast. Lurøy, near the Arctic Circle, gets 2,935 mm (115.6 in) on average, a remarkable amount of precipitation for a polar location. Precipitation is heaviest in autumn and early winter along the coast, while April-to-June is the driest.

The innermost parts of the long fjords are somewhat drier: annual precipitation in Lærdal is 491 mm (19.3 in), in Levanger 750 mm (29.5 in), and only 300 mm (11.8 in) in Skibotn at the head of Lyngenfjord, the latter also having the national record for clear-weather days. The regions east of the mountains (including Oslo) have a more continental climate, with less precipitation, and enjoy more sunshine and usually warmer summers.

Precipitation is highest in summer and early autumn (often with brief, heavy showers) while winter and spring tend to be driest inland. Valleys surrounded by mountains can be very dry compared to nearby areas, and a large area in the interior of Finnmark gets less than 400 mm (15.7 in) of precipitation annually. Svalbard Airport has the lowest average annual precipitation with 190 mm (7.5 in), while Skjåk has the lowest average on the mainland, with only 278 mm (10.9 in). The lowest ever recorded on the mainland is 64 mm (2.5 in) at Hjerkinn in Dovre.

Monthly averages vary from 5 mm (0.20 in) in April in Skjåk to 454 mm (17.9 in) in September in Brekke. Coastal areas from Lindesnes north to Vardø have more than 200 days per year with precipitation; however, this is with a very low threshold value (0.1 mm precipitation). The average annual number of days with at least 3 mm (0.12 in) precipitation is 77 in Blindern/Oslo, 96 in Kjevik/Kristiansand, 158 in Florida/Bergen, 93 in Værnes/Trondheim, and 109 in Tromsø.[9]

Temperature

The coast experiences milder winters than other areas at the same latitudes. The average temperature differences between the coldest month and the warmest is only 10–15 °C (18–27 °F) in coastal areas; some lighthouses have a yearly amplitude of just 10 °C (18 °F), such as Svinøy in Herøy with a coldest month of 2.7 °C (36.9 °F).[10] The differences of inland areas are larger, with a maximum difference of 30 °C (54 °F) in Karasjok. Finnmarksvidda has the coldest winters in mainland Norway, but inland areas much further south can also experience severe cold. Røros has recorded −50 °C (−58 °F) and Tynset has a January average of −13 °C (9 °F).

The islands of southern Lofoten are the most northerly locations in the world where all winter months have mean temperatures above 0 °C (32 °F).[11] Spring is the season when the temperature differences between the southern and northern part of the country is largest; this is also the time of year when daytime and nighttime temperatures differ the most. Inland valleys and the innermost fjord areas have less wind and see the warmest summer days. The Oslofjord lowland is warmest with 24 July-hr average of 17 °C (62.6 °F), but even Alta, at 70°N, has a July average of 13.5 °C (56.3 °F). Commercial fruit orchards are common in the innermost areas of the western fjords, but also in Telemark. Inland areas reach their peak warmth around mid-July and coastal areas by the first half of August. Humidity is usually low in summer.

The North Atlantic Current splits in two over the northern part of the Norwegian Sea, one branch going east into the Barents Sea and the other going north along the west coast of Spitsbergen. This modifies the Arctic polar climate somewhat and results in open water throughout the year at higher latitudes than any other place in the Arctic. On the eastern coast of the Svalbard archipelago, the sea used to be frozen during most of the year, but the last years' warming (graph) have seen open waters noticeably longer.

Normal monthly averages range from −17.1 °C (1.2 °F) in January in Karasjok 129 m (423 ft) amsl[12] to 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) in July in Oslo – Studenterlunden 15 m (49 ft) amsl.[13] The warmest yearly average temperature is 7.7 °C (45.9 °F) in Skudeneshavn, in Karmøy, and the coldest is −3.1 °C (26.4 °F) in Sihccajavri, in Kautokeino, (excluding higher mountains and Svalbard). This is a 10.8 °C (19.4 °F) difference, about the same as the temperature difference between Skudeneshavn and Athens, Greece.[14]

The warmest temperature ever recorded in Norway is 35.6 °C (96.1 °F) in Nesbyen. The coldest temperature ever is −51.4 °C (−60.5 °F) in Karasjok. The warmest month on record was July 1901 in Oslo, with a mean 24-hour temperature of 22.7 °C (72.9 °F)), and the coldest month was February 1966 in Karasjok, with a mean of −27.1 °C (−16.8 °F). Southwesterly winds further warmed by a foehn wind can give warm temperatures in narrow fjords in winter: Tafjord has recorded 17.9 °C (64.2 °F) in January and Sunndal 18.9 °C (66.0 °F) in February.

Compared to coastal areas, inland valleys and the innermost fjord areas have larger diurnal temperature variations, especially in spring and summer. In July, the average daily high temperature is 20.1 °C (68.2 °F) in Lærdal and 17.8 °C (64.0 °F) in Karasjok, roughly 3 °C (5.4 °F) warmer than coastal locations at the same latitude.

| Location | Elevation | Temperature (°C) | Precip | GS/FFD (days) | Summer (days) | Snow >25 cm (days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | April | July | Oct | year | ||||||

| Blindern/Oslo | 94 m | -4.3/-1.8 | 4.5 | 16.4/21.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 763 mm | 188 / 177 | 133 | 30 |

| Oslo Airport, Gardermoen | 202 m | -7.2/-3.9 | 2.8 | 15.2/20.7 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 862 mm | 172 / 145 | 115 | 76 |

| Lillehammer | 242 m | -9.1/- | 2.3 | 14.7/20.8 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 660 mm | 165 / 138 | 108 | 110 |

| Geilo | 810 m | -8.2/-4.5 | -1.1 | 11.2/16.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 700 mm | 127 / 84 | 67 | 162 |

| Sognefjellhytta in Lom (Sognefjell) | 1413 m | -10.7/- | -5.8 | 5.7/10.2 | -2.1 | -3.1 | 860 mm | 58 / - | 0 | 244 |

| Tønsberg | 10 m | -3.2/- | 4.6 | 16.8/- | 7.3 | 6.3 | 930 mm | 194 / - | 136 | 9 |

| Kristiansand | 22 m | -0.9/1.3 | 5.2 | 15.7/20.1 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 1380 mm | 205 / 174 | 145 | 21 |

| Sola/Stavanger | 7 m | 0.8/3.1 | 5.5 | 14.2/17.9 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 1180 mm | 215 / 198 | 144 | 0 |

| Bergen | 12 m | 1.3/3.6 | 5.9 | 14.3/17.6 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 2250 mm | 215 / 208 | 143 | 3 |

| Lærdal | 24 m | -2.5/0.8 | 5.2 | 14.7/20.1 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 491 mm | 193 / 154 | 124 | 0 |

| Årø/Molde | 3 m | -0.3/- | 4.6 | 13.9/- | 6.8 | 6.3 | 1640 mm | 198 / 186 | 115 | 54 |

| Kongsvoll in Oppdal (Dovrefjell) | 885 m | -9.8/-5.5 | -2.5 | 9.9/14.8 | 1.4 | -0.3 | 445 mm | 115 / 65 | 9 | 127 |

| Værnes/Trondheim | 12 m | -3.4/0.1 | 3.6 | 13.7/18.4 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 892 mm | 180 / 154 | 114 | 14 |

| Brønnøysund | 5 m | -1.1/- | 3.7 | 13.1/- | 6.6 | 5.6 | 1510 mm | 186 / - | 108 | 9 |

| Fauske | 14 m | -4.1/- | 1.9 | 13.0/16.9 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 1040 mm | 163 / - | 95 | 88 |

| Helle/Svolvær (Lofoten) | 9 m | -1.1/1.2 | 1.9 | 12.3/15.2 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 1500 mm | 167 / 163 | 81 | 39 |

| Bardufoss | 76 m | -10.4/-5.9 | -0.2 | 13.0/17.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 652 mm | 134 / 113 | 77 | 126 |

| Langnes/Tromsø | 8 m | -3.8/-1.4 | 0.7 | 11.8/15.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1000 mm | 139 / 137 | 65 | 160 |

| Kautokeino (Finnmarksvidda) | 330 m | -15.9/-11.1 | -4.1 | 12.4/16.5 | -1.9 | -2.5 | 360 mm | 113 / 84 | 64 | 135 |

| Kirkenes | 10 m | -11.5/-8.2 | -2.0 | 12.6/16.1 | 0.9 | -0.2 | 450 mm | 125 / 118 | 65 | 140 |

| Longyearbyen/Svalbard | 28 m | -14.6/- | -11.0 | 6.5/8.6 | -5.5 | -6.0 | 210 mm | 50 / - | 0 | 34 |

| Average daily high for January is added, snow will start to melt when temperatures exceeds 0 °C. Average daily high for July is added as summer warmth is significant for vegetation patterns/biomes. Kongsvoll/Dovrefjell daily high data from Fokstugu (973 m). Fauske average daily high data based on data from Narvik, Svolvær average high from Skrova, Kautokeino daily high from Sihccajavri (382 m), Kirkenes daily high data from Kirkenes airport 1964-1990 (89 m). Sognefjellhytta: Mountain lodge above treeline on the western side of Jotunheimen, daily high for July based on 21 years from 1979-2010 (some missing years in data) GS/FFD: Growing season/Frost-free days: Growing season is the period of the year when the 24-hour average temperature reaches 5 °C and lasting until it drops below in autumn. Frost-free days is the average length of the frost free period from the last overnight frost in spring to the first frost in autumn (base period for FFD is 1995-2010); some Arctic-alpine plants can grow in temperatures almost down to 0 °C. FFD from nearby locations: Kristiansand airport Kjevik for Kristiansand, Tafjord for Molde, Fokstugu (973 m) for Dovrefjell, Bodø Airport for Svolvær, Kirkenes airport for Kirkenes. Summer: Number of days/year with 24-hour average temperature at least 10 °C; based on average temperature calculated for each day of the year giving a smooth curve; by this definition summer starts 12 May in Oslo and Bergen, 21 May in Trondheim and 11 June in Bardufoss. Snow: Number of days/year with at least 25 cm (9.8 in) snow cover on the ground; 1971–2000 base period. Snow cover data from nearby locations: Slagentangen is used for Tønsberg, Kjevik for Kristiansand, Rørvik for Brønnøysund, Leknes Airport for Svolvær, Karasjok for Kautokeino, Neiden for Kirkenes and Svalbard Airport snow data (1976–2000 base period) is used for Longyearbyen and also used for July high (1978–90). Tromsø snow data from the meteorological station (100 m); Molde snow data from Nøisomhed, Molde (14 m, 1979 - 87 base period), Kongsvoll snow data 1957 - 77 base period. | ||||||||||

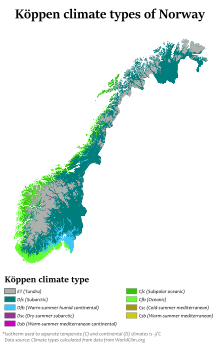

As seen from the table, Norway's climate shows large variations; but with the exception of a small area along the northeastern coast in Finnmark, all areas below the treeline (populated areas) of the Norwegian mainland have temperate or subarctic climates (Köppen groups C and D). Svalbard and Jan Mayen have a polar climate (Köppen group E). More specifically, the climate is maritime mild temperate / marine west coast (Köppen: Cfb) along the southwestern and part of the southern coast, as at Bergen and Kristiansand; hemiboreal / humid continental (Dfb) in the lowlands in the southeast, as at Oslo; cool maritime/subpolar oceanic (Cfc) along the northwestern coastal areas, as at Svolvær; continental subarctic climate (Dfc) in inland valleys and highlands below the treeline in much of the country and reaching to the coast in the northernmost part, as at Geilo, Bardufoss, and Kirkenes; and alpine tundra climate above the treeline in mountain areas all over the country, as at Dovrefjell and Sognefjell. Polar tundra (ET) is found at Jan Mayen and on the Svalbard archipelago, including Longyearbyen, and also includes a narrow area along the northeastern coast from Nordkapp to Vardø on the mainland. True ice cap climate (EF) can only be found at elevations higher than approximately 400–800 metres (1,300–2,600 ft) on Svalbard and Jan Mayen, with the lowest temperatures at Nordaustlandet.

Climate since 1990

Temperatures have tended to be higher in recent years, which may be a consequence of global warming. Using the same data source but with the more recent 20-year period 1991-2010 as a base period, this results in winter temperatures for the same stations that are 1 to 2.5 °C (1.8 to 4.5 °F) higher, while July 24-hr average temperatures increase by approximately 1 °C (34 °F). For Blindern/Oslo, the 1991-2010 period gives a January average of −2.4 °C (27.7 °F) and a July 24-hour average of 17.4 °C (63.3 °F). For Bergen the corresponding temperatures are 2.6 and 15.5 °C (36.7 and 59.9 °F), for Værnes/Trondheim −1.0 and 15.1 °C (30.2 and 59.2 °F), and for Langnes/Tromsø −2.5 and 12.1 °C (27.5 and 53.8 °F). Compared to the 1961-90 period, a much larger area along the coast, from Kristiansand north to Svolvær, has average temperatures above freezing all year.[15]

As a consequence of warming, summers last longer and winters are getting shorter. Snow cover has tended to decrease in those lowland areas where winter temperatures often hover around freezing (including most major cities), while winter precipitation in the mountains and cold inland areas falls as snow, and might have increased in higher mountain areas. Using these recent twenty years as a base period would result in substantial areas in Norway being classified in a different climate zone compared to 1961–90. Oslo and Trondheim would be maritime temperate (Cfb), Tromsø cool maritime (Cfc), and Lillehammer, earlier located at the intersection between subarctic (Dfc) and humid continental (Dfb) climate, would be firmly humid continental. Substantial mountain areas above the treeline would eventually be wooded. The strongest warming has been observed on Svalbard, where the years 2005–2007 have been the warmest ever observed.[16] In addition to warming, precipitation has increased on the mainland, especially in autumn and winter, increasing erosion and the risk of landslides.

Biological diversity

Due to the large latitudinal range of the country and its varied topography and climate, Norway has a higher number of habitats than almost any other European country. There are approximately 60,000 species of plant and animal life in Norway and adjacent waters. The Norwegian Shelf large marine ecosystem is considered highly productive.[17] The total number of species include 16,000 species of insects (probably 4,000 more species yet to be described), 20,000 species of algae, 1,800 species of lichen, 1,050 species of mosses, 2,800 species of vascular plants, up to 7,000 species of fungi, 450 species of birds (250 species nesting in Norway), 90 species of mammals, 45 species of freshwater fish, 150 species of saltwater fish, 1,000 species of freshwater invertebrates and 3,500 species of saltwater invertebrates.[18] About 40,000 of these species have been scientifically described. In the summer of 2010, scientific exploration in Finnmark discovered 126 species of insects new to Norway, of which 54 species were new to science.[19]

The 2006 IUCN Red List names 3,886 Norwegian species as endangered,[20] 17 of which, such as the European beaver, are listed because they are endangered globally, even if the population in Norway is not seen as endangered. There are 430 species of fungi on the red list, many of these are closely associated with the small remaining areas of old-growth forests.[21] There are also 90 species of birds on the list and 25 species of mammals. As of 2006, 1,988 current species are listed as endangered or vulnerable, of which 939 are listed as vulnerable, 734 as endangered, and 285 as critically endangered in Norway, among them the gray wolf, the Arctic fox (healthy population on Svalbard), and the pool frog.

The largest predator in Norwegian waters is the sperm whale, and the largest fish is the basking shark. The largest predator on land is the polar bear, while the brown bear is the largest predator on the Norwegian mainland, where the common moose is the largest animal.

Flora

.png)

Natural vegetation in Norway varies considerably, as can be expected in a country having such variations in latitude. There are generally fewer species of trees in Norway than in areas in western North America with a similar climate. This is because European north–south migration routes after the ice age are more difficult, with bodies of water (such as the Baltic Sea and the North Sea) and mountains creating barriers, while in America land is contiguous and the mountains follow a north–south direction. However, recent research using DNA-studies of spruce and pine and lake sediments have proven that Norwegian conifers survived the ice age in ice-free refuges to the north as far as Andøya.[22] Many imported plants have been able to bear seed and spread. Less than half of the 2,630 plant species in Norway today actually occur naturally in the country.[23] About 210 species of plants growing in Norway are listed as endangered, 13 of which are endemic.[24] The national parks in Norway are mostly located in mountain areas; about 2% of the productive forests in the country are protected.[25]

Some plants are classified as western due to their need for high humidity or low tolerance of winter frost; these will stay close to the southwestern coast, with their northern limit near Ålesund. Some examples are holly and bell heather. Some western species occur as far north as Helgeland (such as Erica tetralix), some even as far as Lofoten (such as Luzula sylvatica).

The mild temperatures along the coast allow for some surprises. Some hardy species of palm grow as far north as Sunnmøre. One of the largest remaining Linden forests in Europe grows at Flostranda, in Stryn.[26] Planted deciduous trees, such as horse chestnut and beech, thrive north of the Arctic Circle (as at Steigen).

Plants classified as eastern need comparatively more summer sunshine, with less humidity, but can tolerate cold winters. These will often occur in the southeast and inland areas: examples being Daphne mezereum, Fragaria viridis, and spiked speedwell. Some eastern species common to Siberia grow in the river valleys of eastern Finnmark. There are species which seem to thrive in between these extremes, such as the southern plants, where both winter and summer climate is important (such as pedunculate oak, European ash, and dog's mercury). Other plants depend on the type of bedrock.

There is a considerable number of alpine species in the mountains of Norway. These species can not tolerate summers that are comparatively long and warm, nor are they able to compete with plants adapted to a longer and warmer growing season. Many alpine plants are common in the North Boreal zone and some in the Middle Boreal zone, but their main area of distribution is on the alpine tundra in the Scandinavian Mountains and on the Arctic tundra. Many of the hardiest species have adapted by ripening seeds over more than one summer. Examples of alpine species are glacier buttercup, Draba lactea, and Salix herbacea. A well-known anomaly is the 30 American alpine species, which in Europe only grow in two mountainous parts of Norway: the Dovre–Trollheimen and Jotunheim mountains in the south; and the Saltdal, to western Finnmark, in the north.[27] Other than in Norway, these species—such as Braya linearis and Carex scirpoidea—grow only in Canada and Greenland. It is unknown whether these survived the ice age on some mountain peak penetrating the ice, or spread from further south in Europe, or why did they not spread to other mountainous regions of Europe. Some alpine species have a wider distribution and grow in Siberia, such as Rhododendron lapponicum (Lapland rosebay). Other alpine species are common to the whole Arctic and some grow only in Europe, such as globe-flower.

The following vegetation zones in Norway are all based on botanical criteria,[28] although, as mentioned, some plants will have specific demands. Forests, bogs, and wetlands, as well as heaths, are all included in the different vegetation zones. A South Boreal bog will differ from a North Boreal bog, although some plant species might occur on both.

Nemoral

A small area along the southern coast—from Soknedal in southern Rogaland and east to Fevik in Aust-Agder (including Kristiansand)—belongs to the Nemoral vegetation zone. This zone is located below 150 metres (490 ft) above sea level and at most 30 kilometres (19 mi) inland along the valleys. This is the predominant vegetation zone in Europe north of southern France, the Alps, the Carpathians, and the Caucasus. The hallmark of this zone in Norway is the predominance of oak and the virtually complete lack of typical boreal species such as Norway spruce and grey alder, although a lowland variant of pine occurs. Nemoral covers a total of 0.5% of the land area (excluding Svalbard and Jan Mayen).

Hemiboreal (Boreonemoral)

The hemiboreal zone covers a total of 7% of the land area in Norway, including 80% of Østfold and Vestfold. This vegetation represents a mix of nemoral and boreal plant species, and belongs to the Palearctic, Sarmatic mixed forests terrestrial ecoregion (PA0436). The nemoral species tend to predominate on slopes facing southwest and with good soil, while the boreal species predominate on slopes facing north and with waterlogged soil. In some areas, other factors overrule this, such as where the bedrock gives little nutrient, where oak and the boreal pine often share predominance. The boreonemoral zone follows the coast from Oslofjord north to Ålesund, becoming discontinuous north of Sunnmøre. In Oslo, this zone reaches to an elevation of 200 metres (660 ft) above sea level. It also reaches into some of the lower valleys and just reaches the lowland around Mjøsa, but not as far north as Lillehammer. In the valleys of the south, this vegetation might exist up to 300–400 metres (980–1,310 ft) above sea level. The zone follows the lowland of the west coast and into the largest fjords, reaching an elevation of 150 metres (490 ft) there, even to 300 metres (980 ft) in some sheltered fjords and valleys in Nordmøre, with nutrient-rich soil. The northernmost locations in the world are several areas along the Trondheimsfjord, such as Frosta, with the northernmost location being Byahalla, in Steinkjer. Some nemoral species in this zone are English oak, sessile oak, European ash, elm, Norway maple, hazel, black alder, lime, yew, holly (southwest coast), wild cherry, ramsons, beech (a late arrival only common in Vestfold), and primrose. Typical boreal species are Norway spruce, pine, downy birch, grey alder, aspen, rowan, wood anemone, and Viola riviniana.

Boreal

Boreal species are adapted to a long and cold winter, and most of these species can tolerate colder winter temperatures than winters in most of Norway. Thus they are distinguished by their need for growing season length and summer warmth. Bogs are common in the boreal zone, with the largest areas in the North and Middle Boreal Zones, as well as in the area just above the tree line. The large boreal zone is usually divided into three subzones: South Boreal, Middle Boreal, and North Boreal.

Boreal ecoregions

The boreal zones in Norway belong to three ecoregions. The area dominated by spruce forests (some birch, pine, willow, aspen) mostly belong to the Scandinavian and Russian taiga ecoregion (PA0608). The Scandinavian coastal conifer forests ecoregion (PA0520) in coastal areas with mild winters and frequent rainfall follows the coast from south of Stavanger north to southern Troms and includes both hemiboreal and boreal areas. Bordering the latter region is the Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands ecoregion (PA1110). This region seems to include both mountain areas with alpine tundra and lowland forests, essentially all the area outside the natural range of Norway spruce forests.[29] This ecoregion thus shows a very large range of climatic and environmental conditions, from the temperate forest along the fjords of Western Norway to the summit of Galdhøpiggen, and northeast to the Varanger Peninsula. The area above the conifer treeline is made up of mountain birch Betula pubescens-czerepanovii (fjellbjørkeskog). The Scots pine reaches its altitudinal limit about 200 metres (660 ft) lower than the mountain birch.

South Boreal

The South Boreal zone (SB) is dominated by boreal species, especially Norway spruce, and covers a total of 12% of the total land area. The SB is the only boreal zone with a few scattered—but well-developed—warmth-demanding broadleaf deciduous trees, such as European ash and oak. Several species in this zone need fairly warm summers (SB has 3–4 months with a mean 24-hr temperature of at least 10 °C (50 °F)), and thus are very rare in the middle boreal zone. Some of the species not found further north are black alder, hop, oregano, and guelder rose. This zone is found above the hemiboreal zone, up to 450 metres (1,480 ft) amsl in Østlandet and 500 metres (1,600 ft) in the most southern valleys. In the eastern valleys it reaches several hundred kilometers into Gudbrandsdal and Østerdal, and up to Lom and Skjåk, in Ottadalen. Along the southwestern coast, the zone reaches an elevation of 400 metres (1,300 ft) at the head of large fjords (such as in Lærdal), and about 300 metres (980 ft) nearer to the coast. Norway spruce is lacking in Vestlandet (Voss is an exception). North of Ålesund, SB vegetation predominates in the lowland down to sea level, including islands such as Hitra. Most of the lowland in Trøndelag below 180 metres (590 ft) elevation is SB, up to 300 metres (980 ft) above sea level in inland valleys such as Gauldalen and Verdalen, and up to 100 metres (330 ft) in Namdalen. The coastal areas and some fjord areas further north—such as Vikna, Brønnøy, and the best locations along the Helgeland coast—is SB north to the mouth of Ranfjord, while inland areas north of Grong are dominated by Middle Boreal zone vegetation in the lowland. There are small isolated areas with SB vegetation further north, as in Bodø and Fauske, the most northern location being a narrow strip along the northern shore of Ofotfjord; and the endemic Nordland-whitebeam only grows in Bindal.[30] Agriculture in Norway, including grain cultivation, takes place mostly in the hemiboreal and SB zones.

Middle Boreal

The typical closed-canopy forest of the Middle Boreal (MB) zone is dominated by boreal plant species. The MB vegetation covers a total of 20% of the total land area. Norway spruce is the dominant tree in large areas in the interior of Østlandet, Sørlandet, Trøndelag, and Helgeland and the MB and SB spruce forests are the commercially most important in Norway. Spruce does not grow naturally north of Saltfjell in mid-Nordland (the Siberian spruce variant occurs in the Pasvik valley), due to mountain ranges blocking their advance, but is often planted in MB areas further north for economic reasons, contributing to a different landscape. Birch is usually dominant in these northern areas; but pine, aspen, rowan, bird cherry and grey alder are also common. This MB birch is often a cross between silver birch and downy birch and is taller (6–12 metres (20–39 ft)) than the birch growing near the tree line. Conifers will grow taller. Some alpine plants grow in the MB zone; nemoral species are rare. The understory (undergrowth) is usually well developed if the forest is not too dense. Many plants do not grow further north: grey alder, silver birch, yellow bedstraw, raspberry, mugwort, and Myrica gale are examples of species in this zone that do not grow further north or higher up. MB is located at an altitude of 400–750 metres (1,310–2,460 ft) in Østlandet, up to 800 metres (2,600 ft) in the southern valleys, 300–600 metres (980–1,970 ft) (800 metres (2,600 ft) at the head of the long fjords) on the southwest coast, and 180–450 metres (590–1,480 ft) in Trøndelag (700 metres (2,300 ft) in the interior, as at Røros and Oppdal). Further north, MB is common in the lowland: up to 100 metres (330 ft) above sea level in Lofoten and Vesterålen, 200 metres (660 ft) at Narvik, 100 metres (330 ft) at Tromsø, 130–200 metres (430–660 ft) in inland valleys in Troms, and the lowland at the head of Altafjord is the most northerly area of any size—small pockets exist at Porsanger and Sør-Varanger. This is usually the most northerly area with some farming activity, and barley was traditionally grown even as far north as Alta.

North Boreal

The North Boreal (NB) zone, (also known as open or sparse taiga) is the zone closest to the tree line, bordering the alpine or polar area, and dominated by a harsh subarctic climate. There are at least 30 summer days with a mean temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) or more, up to about two months. The trees grow very slowly and generally do not get very large. The forest is not as dense as further south or at lower altitudes and is known as the mountain forest (Fjellskog). The NB zone covers a total of 28% of the total land area of Norway, including almost half of Finnmark, where the mountain birch grows down to sea level. The lower part of this zone also has conifers, but the tree line in Norway is mostly formed by mountain birch, a subspecies of downy birch (subspecies czerepanovii),[31] which is not to be confused with dwarf birch). Spruce and pine make up the tree line in some mountain areas with a more continental climate. Alpine plants are common in this zone. The birch forest 1,320 metres (4,330 ft) above sea level at Sikilsdalshorn is the highest tree line in Norway. The tree line is lower closer to the coast and in areas with lower mountains, due to cooler summers, more wind near mountain summits, and more snow in the winter (coastal mountains) leading to later snowmelt. The NB zone covers large areas at 750–950 metres (2,460–3,120 ft) altitude in the interior of Østlandet; is 800–1,200 metres (2,600–3,900 ft) in the central mountain areas; but at the western coast the tree line is down to about 500 metres (1,600 ft) above sea level, increasing significantly in the long fjords (1,100 metres (3,600 ft) at the head of Sognefjord). Further north, large areas in the interior highlands or uplands of Trøndelag and North Norway are dominated by the NB zone, with the tree line at about 800 metres (2,600 ft) amsl in the interior of Trøndelag, 600 metres (2,000 ft) in Rana, 500 metres (1,600 ft) at Narvik, 400 metres (1,300 ft) at Tromsø, 200 metres (660 ft) at Kirkenes and 100 metres (330 ft) at Hammerfest (only pockets in sheltered areas). The large Finnmarksvidda plateau is at an altitude placing it almost exactly at the tree line. The last patch of NB zone gives way to tundra at sea level about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of the North Cape plateau (near Skarsvåg). Areas south of this line are tundra-like with scattered patches of mountain birch woodland (forest tundra) and become alpine tundra even at minor elevations. The trees near the tree line are often bent by snow, wind, and growing-season frost; and their height is only 2–4 metres (6 ft 7 in–13 ft 1 in). Outside Norway (and adjacent areas in Sweden), the only other areas in the world with the tree line mostly made up by a small-leaved deciduous tree such as birch—in contrast to conifers—are Iceland and the Kamtschatka peninsula.

The presence of a conifer tree line is sometimes used (Barskoggrense) to divide this zone into two subzones, as the conifers will usually not grow as high up as the mountain birch. Spruce and pine grow at nearly 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) above sea level in some areas of Jotunheimen, down to 400 metres (1,300 ft) in Bergen (900 metres (3,000 ft) at the head of Sognefjord), 900 metres (3,000 ft) at Lillehammer (mountains near Oslo are too low to have a tree line), 500 metres (1,600 ft) at Trondheim (750 metres (2,460 ft) at Oppdal), 350 metres (1,150 ft) at Narvik, 200 metres (660 ft) at Harstad, 250 metres (820 ft) at Alta; and the most northerly pine forest in the world is in Stabbursdalen National Park in Porsanger. There are some forests in this part of the NB zone; and some conifers can grow quite large even if growth is slow.

Tundra

Alpine tundra is common in Norway, covering a total of 32% of the land area (excluding Svalbard and Jan Mayen) and belonging to the Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands ecoregion (PA1110). The area closest to the tree line (low alpine) has continuous plant cover, with willow species such as Salix glauca, S. lanata, and S. lapponum (0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in) tall); blueberry, common juniper, and twinflower are also common. The low alpine area was traditionally used as summer pasture, and in part still is. This zone reaches an elevation of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) in Jotunheimen, including most of Hardangervidda; 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) in eastern Trollheimen; and about 800 metres (2,600 ft) at Narvik and the Lyngen Alps. Higher up (mid-alpine tundra) the plants become smaller; mosses and lichens are more predominant; and plants still cover most of the ground, even if snowfields lasting into mid-summer and permafrost are common. At the highest elevations (high-alpine tundra) the ground is dominated by bare rock, snow, and glaciers, with few plants.

_2.jpg)

The highest weather station in Norway—Fanaråken in Luster, at 2,062 metres (6,765 ft)—has barely three months of above freezing temperatures and a July average of 2.7 °C (36.9 °F). Still, glacier buttercup has been found only 100 metres (330 ft) below the summit of Galdhøpiggen, and mosses and lichens have been found at the summit.

In northeastern Finnmark (northern half of the Varanger Peninsula and the Nordkinn Peninsula) is a small lowland tundra area which is often considered part of the Kola Peninsula tundra ecoregion (PA1106). Svalbard and Jan Mayen have tundra vegetation except for areas covered by glaciers; and some areas, such as the cliffs at southern Bear Island, are fertilized by seabird colonies. This tundra is often considered part of the Arctic Desert ecoregion (PA1101). The lushest areas on these Arctic islands are sheltered fjord areas at Spitsbergen; they have the highest summer temperatures and the very dry climate makes for little snow and thus comparatively early snowmelt. The short growing season and the permafrost underneath the active layer provide enough moisture. Plants include dwarf birch, cloudberry, Svalbard poppy, and harebell.

A warmer climate would push the vegetation zones significantly northwards and to higher elevations.[32]

Natural resources

In addition to oil and natural gas, hydroelectric power, and fish and forest resources, Norway has reserves of ferric and nonferric metal ores. Many of these have been exploited in the past but whose mines are now idle because of low-grade purity and high operating costs. Europe's largest titanium deposits are near the southwest coast. Coal is mined in the Svalbard islands.

Resources: Petroleum, copper, natural gas, pyrites, nickel, iron ore, zinc, lead, fish, lumber, hydropower.

Land use

Arable land: 3.3% (in use; some more marginal areas are not in use or used as pastures)

- Permanent crops: 0%

- Permanent pastures: 0%

- Forests and woodland: 38% of land area is covered by forest, 21% by conifer forest, and 17% by deciduous forest,[33][34] increasing as many pastures in the higher elevations and some coastal, man-made heaths are no longer used or reforested, as well as increase due to warmer summers

- Other: 59% (mountains and heaths 46%, bogs and wetlands 6.3%, lakes and rivers 5.3%, urban areas 1.1%)[35]

Irrigated land: 970 km2 (370 sq mi), 1993 estimate

Natural hazards:

- European windstorms with hurricane-strength winds along the coast and in the mountains are not uncommon. For centuries one out of four males in coastal communities were lost at sea.

- Avalanches on steep slopes, especially in the northern part of the country and in mountain areas.

- Landslides have on occasions killed people, mostly in areas with soil rich in marine clay, as in lowland areas near Trondheimsfjord.

- Tsunamis have killed people; usually caused by parts of mountains (rockslide) falling into fjords or lakes. This happened 1905 in Loen in Stryn when parts of Ramnefjell fell into Loenvatnet lake, causing a 40-metre (130 ft) tsunami which killed 61 people. It happened again in the same place in 1936, this time with 73 victims. 40 people were killed in Tafjord in Norddal in 1934.[36]

Environmental concerns

Current issues

Environmental concerns in Norway include how to cut greenhouse gas emissions, pollution of the air and water, loss of habitat, damage to cold-water coral reefs from trawlers, and salmon fish farming threatening the wild salmon by spawning in the rivers, thereby diluting the fish DNA. Acid rain has damaged lakes, rivers and forests, especially in the southernmost part of the country, and most wild salmon populations in Sørlandet have died. Due to lower emissions in Europe, acid rain in Norway has decreased by 40% from 1980 to 2003.[37] Another concern is a possible increase in extreme weather. In the future, climate models[38] predict increased precipitation, especially in the areas with currently high precipitation, and also predict more episodes with heavy precipitation within a short period, which can cause landslides and local floods. Winters will probably be significant milder, and the sea-ice cover in the Arctic ocean might melt altogether in summer, threatening the survival of the polar bear on Svalbard. Both terrestrial and aquatic species are expected to shift northwards, and this is already observed for some species; the growing red deer population is spreading northwards and eastwards, with 2008 being the first hunting season which saw more red deer (35,700) than moose shot.[39] Migratory birds are arriving earlier; trees are coming into leaf earlier; mackerel are becoming common in summer off the coast of Troms. The total number of species in Norway are expected to rise due to new species arriving.[40] Norwegians are statistically among the most worried when it comes to global warming and its effects,[41] even if Norway is among the countries expected to be least negatively affected by global warming, with some possible gains.[42]

International agreements

Norway is a party to:

- Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty

- Antarctic Treaty System

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,

- Environmental Modification Convention,

- Law of the Sea

- London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

- Montreal Protocol (ozone layer protection)

- MARPOL 73/78 (ship pollution)

- International Tropical Timber Agreement, 1983

- International Tropical Timber Agreement, 1994

- Kyoto Protocol (climate change)

- ADR (road transport of hazardous materials)

Major cities and towns (in order of decreasing population)

- Oslo (earlier Kristiania) – capital

- Bergen – former capital, Hansa city

- Trondheim – the first capital of Norway, known by the name Nidaros (Viking Age)

- Stavanger (ranked third by population/conurbation)

- Kristiansand

- Fredrikstad

- Tromsø

- Sandnes

- Drammen

- Skien

See also

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Glozman, Igor. "Plate tectonics".

- "Protected Areas and World Heritage - Norway". United Nations Environment Programme. July 2005. Archived from the original on 15 January 2007.

- "Bjerknes centre for climate research:Norways glaciers". uib.no. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- "Norway in the United Kingdom". Norgesportalen.

- "News - NORKLIMA". www.forskningsradet.no. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- "Bronnoysund Norway, Weather History and Climate Data". www.worldclimate.com.

- "Nome, Alaska (U.S.A.) Weather History and Climate Data". www.worldclimate.com.

- "JAKUTSK USSR, Weather History and Climate Data". www.worldclimate.com.

- Lippestad, Heidi, ed. (29 December 2004). "Nedbør" [Precipitation]. Norwegian Meteorological Institute (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Herøy climate". met.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- institutt, NRK og Meteorologisk. "Weather statistics for Værøy helikopterhavn, Tabbisodden". yr.no.

- Lippestad, Heidi, ed. (25 January 2007). "Temperaturnormaler og Nedbørnormaler for Karasjohka–Karasjok i perioden 1961–1990" [Temperature and Precipitation for Karasjohka-Karasjok, 1961–1990]. Norwegian Meteorological Institute (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Lippestad, Heidi, ed. (5 January 2004). "Temperaturnormaler og Nedbørnormaler for Oslo i perioden 1961–1990" [Temperature and Precipitation for Oslo, 1961–1990]. Norwegian Meteorological Institute (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 10 February 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Athens (Hellinikon), Greece Weather History and Climate Data". www.worldclimate.com.

- "Map". met.no. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- "Svalbard temperature history". met.no. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- Norwegian Shelf ecosystem Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- NOU 2004 Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Stadig flere insekter oppdages i Finnmark" [More and more insects are being found in Finnmark]. Artsdatabanken (in Norwegian). 2006. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Artsdatabanken:Norwegian Red List 2006 Archived 20 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Panda.org:Norway forest heritage

- "Sturdy Scandinavian conifers survived Ice Age". sciencedaily.com.

- "Plants in Norway". environment.no. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- "Plant talk.org". plant-talk.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "26 nye skogreservater". forskning.no. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- "Flostranda nature reserve". miljostatus.no. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- Gjærevoll, 1992, pp 146–160; Moen, 1998, p. 52

- Moen, 1998; Gjærevoll 1992

- "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- "Reppen nature reserve". miljostatus.no. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- Taulavuori, K.M.J.; et al. (2004). "Dehardening of mountain birch (Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii) ecotypes at elevated winter temperatures". New Phytologist. 162: 427–436. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2019 – via Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute.

- "Fact sheet" (PDF). uio.no. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Boreal Forests of the World - NORWAY - FORESTS AND FORESTRY". www.borealforest.org.

- "Statistics". miljostatus.no. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Moen, Asbjørn; Lillethun, Arvid, eds. (1999). Nasjonalatlas for Norge: Vegetasjon. Statens Kartverk. ISBN 9788290408263.

- Furseth, A. (1994). Dommedagsfjellet: Tafjord 1934. Oslo: Gyldendal. Cited in Rød, Sverre Kjetil; Botan, Carl; Holen, Are (June 2012). "Risk communication and worried publics in an imminent rockslide and tsunami situation". Journal of Risk Research. 15 (6): 645–654. doi:10.1080/13669877.2011.652650.

- "Sur Nedbør" [Acid Rain]. Miljøstatus i Norge [Environmental Status in Norway] (in Norwegian). 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Norges klima om 50–100 år" [Norway's climate in 50–100 years]. Miljøstatus i Norge [Environmental Status in Norway] (in Norwegian). 27 December 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Holmemo, Agnete Daae-Qvale (19 March 2009). "Hjortebestand i vill vekst". nrk.no.

- "Impacts in Norway". State of the Environment in Norway. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Flere bekymret over oppvarming, Aftenposten, 6 June 2007, retrieved 11 June 2007. (in Norwegian)

- Sheridan, Barrett (16 April 2007). "Learning to Live with Global Warming". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2019 – via MSNBC.

Sources

- Tollefsrud, J.; Tjørve, E.; Hermansen, P.: Perler i Norsk Natur - En Veiviser. Aschehoug, 1991. ISBN 82-03-16663-6

- Gjærevoll, Olav. "Plantegeografi". Tapir, 1992. ISBN 82-519-1104-4

- Moen, A. 1998. Nasjonalatlas for Norge: Vegetasjon. Statens Kartverk, Hønefoss. ISBN 82-90408-26-9

- Norwegian Meteorological Institute ().

- Bjørbæk, G. 2003. Norsk vær i 110 år. N.W. DAMM & Sønn. ISBN 82-04-08695-4

- Førland, E.. Variasjoner i vekst og fyringsforhold i Nordisk Arktis. Regclim/Cicerone 6/2004.

- University of Oslo. Almanakk for Norge Gyldendal fakta. ISBN 82-05-35494-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geography of Norway. |