Religion in Poland

Poland is one of the most religious countries in Europe.[2] Though varied religious communities exist in Poland, most Poles adhere to Christianity. Within this, the largest grouping is the Roman Catholic Church: 92.9% of the population identified themselves with that denomination in 2015 (census conducted by the Central Statistical Office (GUS));[1][3] according to the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics, 36.7% of Polish Catholic believers attended Sunday Mass in 2015.[4] Poland is one of the most catholic countries in the world, Neal Pease describes Poland as "Rome’s Most Faithful Daughter."[5]

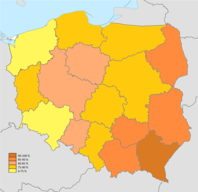

Religion in Poland in 2015 conducted by the Central Statistical Office (GUS)[1]

Roman Catholicism continues to be important in the lives of many Poles, and the Catholic Church in Poland enjoys social prestige and political influence, despite repression experienced under Communist rule.[6] Its members regard it as a repository of Polish heritage and culture.[7] Poland lays claim to having the highest proportion of Roman Catholic citizens of any country in Europe except Malta and San Marino (higher than in Italy, Spain, and Ireland, all countries in which the Roman Catholic Church has been the sole established religion).[8]

The current extent of this numerical dominance results largely from the Holocaust of Jews living in Poland carried out by Nazi Germany and the World War II casualties among Polish religious minorities,[9][10][11][12] as well as the flight and expulsion of Germans, many of whom were not Roman Catholics, at the end of World War II.

The rest of the population consists mainly of Eastern Orthodox (Polish Orthodox Church) (507,196 believers, Polish and Belarusian),[13] various Protestant churches (the largest of which is the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Poland, with 61,217 members)[13] and Jehovah's Witnesses (116,935).[13] There are about 55,000 Greek Catholics in Poland.[13] Other religions practiced in Poland, by less than 0.1% of the population, include Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism.[14]

According to 2015 statistics assembled by Statistics Poland, 94.2% of the population is affiliated with a religion; 3.1% do not belong to any religion. The most practiced religion was Roman Catholicism, whose followers comprised the 92.8% of the population, followed by the Eastern Orthodox with 0.7% (rising from 0.4% in 2011, caused in part by recent immigration from the Ukraine), Jehovah's Witnesses with 0.3%, and various Protestant denominations comprising 0.2% of the Polish population and 0.1 of Greek Catholic Churches.[1]According to the same survey, 61.1% of the population gave religion high to very high importance whilst 13.8% regarded religion as of little or no importance. The percentage of believers is higher in Eastern Poland.

History

For centuries the Slavic people inhabiting the lands of modern day Poland have practiced various forms of paganism known as Rodzimowierstwo (“native faith”).[15][16][17][18] From the beginning of its statehood, different religions coexisted in Poland. With the baptism of Poland in 966, the old pagan religions were gradually eradicated over the next few centuries during the Christianization of Poland. However, this did not put an end to pagan beliefs in the country. The persistence was demonstrated by a series of rebellions known as the Pagan reaction in the first half of the 11th century, which also showed elements of a peasant uprising against landowners and feudalism,[19] and led to a mutiny that destabilized the country.[20][21][22][23] By the 13th century Catholicism had become the dominant religion throughout the country. Nevertheless, Christian Poles coexisted with a significant Jewish segment of the population.[24][25]

In the 15th century, the Hussite Wars and the pressure from the papacy led to religious tensions between Catholics and the emergent Hussite and subsequent Protestant community, particularly after the Edict of Wieluń (1424).[26] The Protestant movement gained a significant following in Poland and, though Roman Catholicism retained a dominant position within the state, the liberal Warsaw Confederation (1573) guaranteed wide religious tolerance.[26] But the reactionary movement succeeded in reducing the scope for tolerance by the late 17th and early 18th century – as evidenced by events such as the Tumult of Toruń (1724).[26][27][28]

When Poland was divided between its neighbors in the late eighteenth century, some Poles were subjected to religious discrimination in the newly expanded Prussia and Russia.[29]

Prior to the Second World War, some 3,500,000 Jews (about 10% of the national population) lived in the Polish Second Republic, largely in cities. Between the Germano-Soviet invasions of Poland and the end of World War II, over 90% of Jews in Poland perished.[30] The Holocaust (also called "Shoah") took the lives of more than three million mostly Ashkenazi Jews in Poland. Comparatively few managed to survive the German occupation or to escape eastward into the territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union, beyond the reach of the Nazi Germany. As elsewhere in Europe during the interwar period, there was both official and popular anti-Semitism in Poland, at times encouraged by the Roman Catholic Church and by some political parties (particularly the right-wing endecja and small ONR groups and factions), but not directly by the Polish government itself.[31]

According to a 2011 survey by Ipsos MORI, 85% of the Poles remain Christians; 8% are irreligious, atheist, or agnostic; 2% adhere to unspecified other religions; and 5% did not answer the question.[32]

The Polish Constitution and religion

The Polish Constitution assures freedom of religion for all. The Constitution also grants national and ethnic minorities the rights to establish educational and cultural institutions and institutions designed to protect religious identity, as well as to participate in the resolution of matters connected with their cultural identities.[34]

Religious organizations in the Republic of Poland can register their institution with the Ministry of Interior and Administration, creating a record of churches and other religious organizations which operate under separate Polish laws. This registration is not necessary, but it does serve the laws guaranteeing freedom of religious practice.

Slavic Rodzimowiercy groups registered with the Polish authorities in 1995 are the Native Polish Church (Rodzimy Kościół Polski), which represents a pagan tradition which goes back to pre-Christian faiths and continues Władysław Kołodziej's 1921 Holy Circle of Worshipper of Światowid (Święte Koło Czcicieli Światowida), and the Polish Slavic Church (Polski Kościół Słowiański).[35] This native Slavic religion is promoted also by the Native Faith Association (Zrzeszenie Rodzimej Wiary, ZRW), and the Association for Tradition founded in 2015.

Major denominations

Around 125 faith groups and minor religions are registered in Poland.[36] Data for 2018 provided by Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Poland's Central Statistical Office.[13]

| Denomination | Members | Leadership |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic Church in Poland,[36] including: Roman Catholic Byzantine-Ukrainian Armenian |

32,910,865 55,000 670 |

Wojciech Polak, Prymas of Poland Stanisław Gądecki, Chairman of Polish Episcopate Salvatore Pennacchio, Apostolic Nuncio to Poland Jan Martyniak, Archbishop Metropolite of Byzantine-Ukrainian Rite |

| Polish Autocephalous Orthodox Church | 507,196 | Metropolitan of Warsaw Sawa |

| Jehovah's Witnesses in Poland | 116,935 | Warszawska 14, Nadarzyn Pl-05830 |

| Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland | 61,217 | Bishop Fr. Jerzy Samiec |

| Pentecostal Church in Poland | 25,152 | Bishop Marek Kamiński |

| Old Catholic Mariavite Church in Poland (data from 2017) |

22,849 | Chief Bishop Fr. Marek Maria Karol Babi |

| Polish Catholic Church (Old Catholic) | 18,259 | Bishop Wiktor Wysoczański |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church in Poland | 9,726 | President of the Church, Ryszard Jankowski |

| Church of Christ in Poland | 6,326 | Bishop Andrzej W. Bajeński |

| New Apostolic Church in Poland | 6,118 | Bishop Waldemar Starosta |

| Christian Baptist Church in Poland • Baptist Union of Poland |

5,343 | President of the Church: Dr. Mateusz Wichary |

| Church of God in Christ | 4,611 | Bishop Andrzej Nędzusiak |

| Evangelical Methodist Church in Poland (data from 2017) |

4,465 | General Superintendent, Andrzej Malicki |

| Evangelical Reformed Church in Poland | 3,335 | President consistory Dr. Witold Brodziński |

| Catholic Mariavite Church in Poland | 1,838 | Bishop Damiana Maria Beatrycze Szulgowicz |

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in Poland | 1,729 | President of the Church: Russel M. Nelson

Warsaw Mission President: Mateusz Turek |

| Islamic Religious Union in Poland | 523 | President of the Supreme Muslim College Stefan Korycki |

| Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland | 1,860 | • President of the Main Board Piotr Kadlčik • Chief Rabbi of Poland Michael Schudrich |

2015 poll by CBOS

According to an opinion poll conducted in "a representative group of 1,000 people" by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS), published in 2015, 39% of Poles claim they are "believers following the Church's laws", while 52% answered that they are "believers in their own understanding and way", and 5% stated that they are atheists.[37][38]

Selected locations

St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral in Poznań

St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral in Poznań Old Catholic Mariavite Temple of Mercy and Charity in Płock

Old Catholic Mariavite Temple of Mercy and Charity in Płock St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral in Legnica

St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral in Legnica

- Roman Catholic Cathedral in Wrocław

Włocławek Cathedral

Włocławek Cathedral St. Stanislaus Kostka Cathedral in Łódź

St. Stanislaus Kostka Cathedral in Łódź Cathedral in Radom

Cathedral in Radom Romanesque church in Czerwińsk by Vistula river

Romanesque church in Czerwińsk by Vistula river- Cathedral in Lublin

-kosc_Rocha_i_Jana_Chrzciciela.jpg) Saint Roch and John Church in Brochów

Saint Roch and John Church in Brochów Cathedral Basilica of the Holy Family in Częstochowa seen from the John Paul II square

Cathedral Basilica of the Holy Family in Częstochowa seen from the John Paul II square Catholic St. Anne's Church in Warsaw

Catholic St. Anne's Church in Warsaw

St. Catherine church in Gdańsk

St. Catherine church in Gdańsk- Eastern Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit in Białystok

Eastern Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral in Warsaw

Eastern Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral in Warsaw

Nożyk Synagogue in Warsaw

Nożyk Synagogue in Warsaw Tempel Synagogue in Kraków

Tempel Synagogue in Kraków Mosque in Kruszyniany

Mosque in Kruszyniany Mosque in Gdańsk

Mosque in Gdańsk

See also

- Roman Catholicism in Poland

- Slavic Native Faith in Poland

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Poland

- Protestantism in Poland

- Islam in Poland

- Buddhism in Poland

- Hinduism in Poland

- History of the Jews in Poland

- Bahá'í Faith in Poland

- Polish anti-religious campaign (1945–1990)

- Irreligion in Poland

References

- GUS. "Infographic - Religiousness of Polish inhabitiants". stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "Co łączy Polaków z parafią? Komunikat z badań" [What Connects Poles with Parish? Training Message] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Centre for Public Opinion Research CBOS. March 2005. Preface. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Sadłoń, Wojciech (ed.). Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2018 (PDF) (in Polish). Warszawa: Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC. p. 4. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.23260.90248.

- Pease, Neal (2009). Rome’s Most Faithful Daughter: The Catholic Church and Independent Poland, 1914–1939. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821443620.

- "Religion in Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Archived 1 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/21/christianity-non-christian-europe-young-people-survey-religion

- Project in Posterum, Poland World War II casualties. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Holocaust: Five Million Forgotten: Non-Jewish Victims of the Shoah. Remember.org.

- AFP/Expatica, Polish experts lower nation's WWII death toll, Expatica.com, 30 August 2009

- Tomasz Szarota & Wojciech Materski, Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami, Warsaw, IPN 2009, ISBN 978-83-7629-067-6 (Introduction online. Archived 1 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Niektóre wyznania religijne w Polsce w 2018 r. (Selected religious denominations in Poland in 2018)". Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2019 (Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland 2019) (PDF) (in Polish and English). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2019. pp. 114–115. ISSN 1640-3630.

- Ciecieląg, Paweł, ed. (2016). Wyznania religijne w Polsce 2012-2014 (PDF). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 142–173. ISBN 9788370276126.

- http://www.polishtoledo.com/pagan/

- Gniazdo – Rodzima wiara i kultura, nr 2(7)/2009 – Ratomir Wilkowski: Rozważania o wizerunku rodzimowierstwa na przykładzie...

- https://rkp.org.pl/

- https://wildhunt.org/2016/07/paganism-in-poland.html

- http://www.krakowpost.com/6956/2013/08/resurgence-of-pre-christian-beliefs-in-poland

- Gerard Labuda (1992). Mieszko II król Polski: 1025–1034 : czasy przełomu w dziejach państwa polskiego. Secesja. p. 102. ISBN 978-83-85483-46-5. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Gerard Labuda (1992). Mieszko II król Polski: 1025–1034 : czasy przełomu w dziejach państwa polskiego. Secesja. p. 102. ISBN 978-83-85483-46-5. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Polska Akademia Nauk. Komitet Słowianoznawstwa (1967). Słownik starożytności słowiańskich: encyklopedyczny zarys kultury słowian od czasów najdawniejszych. Zkład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 247. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

Widziano w M. wodza powstania pogańsko-ludowego

- Oskar Halecki; W: F. Reddaway; J. H. Penson. The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-00-128802-4. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-674-92685-1.

- Jerzy Lukowski; W. H. Zawadzki (6 July 2006). A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-521-85332-3. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Hillar, Marian (1992). "The Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791: Myth and Reality". The Polish Review. 37 (2): 185–207. JSTOR 25778627.

- Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- Beata Cieszynska (2 May 2008). "Polish Religious Persecution as a Topic in British Writing in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century". In Richard Unger; Jakub Basista (eds.). Britain and Poland-Lithuania: Contact and Comparison from the Middle Ages to 1795. BRILL. p. 243. ISBN 90-04-16623-8.

- "Anna M". Web.ku.edu. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Lukas, Richard C. (1989). Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 5, 13, 111, 201. ISBN 978-0-8131-1692-1.

The estimates of Jewish survivors in Poland,.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

—— (2001). The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation, 1939–1944. Hippocrene Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7818-0901-6.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Poland's Holocaust by Tadeusz Piotrowski. Published by McFarland. From Preface: policy of genocide.

- Views on globalisation and faith Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ipsos MORI, 5 July 2011.

- http://stat.gov.pl/en/infographics-and-widgets/infographics/infographic-religiousness-of-polish-inhabitiants,4,1.html

-

- Simpson, Scott (2000). Native Faith: Polish Neo-Paganism At the Brink of the 21st Century

- "Society". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2002. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- Boguszewski, Rafał (February 2015). "ZMIANY W ZAKRESIE PODSTAWOWYCH WSKAŹNIKÓW RELIGIJNOŚCI POLAKÓW PO ŚMIERCI JANA PAWŁA II" (PDF). CBOS. p. 6. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Wierzę w Boga Ojca, ale nie w Kościół powszechny". Oko.press. 23 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.