Carthage

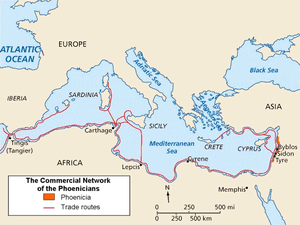

Carthage was the center or capital city of the ancient Carthaginian civilization, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now the Tunis Governorate in Tunisia. Carthage was widely considered the most important trading hub of the Ancient Mediterranean and was arguably one of the most affluent cities of the classical world.

Baths of Antoninus, Carthage | |

Shown within Tunisia | |

| Location | Tunisia |

|---|---|

| Region | Tunis Governorate |

| Coordinates | 36.8528°N 10.3233°E |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 37 |

| State Party | |

| Region | North Africa |

The city developed from a Phoenician colony into the capital of a Punic empire which dominated large parts of the Southwest Mediterranean during the first millennium BC.[1] The legendary Queen Alyssa or Dido is regarded as the founder of the city, though her historicity has been questioned. According to accounts by Timaeus of Tauromenium, she purchased from a local tribe the amount of land that could be covered by an oxhide. Cutting the skin into strips, she laid out her claim and founded an empire that would become, through the Punic Wars, the only existential threat to Rome until the coming of the Vandals several centuries later.[2]

The ancient city was destroyed by the Roman Republic in the Third Punic War in 146 BC and then re-developed as Roman Carthage, which became the major city of the Roman Empire in the province of Africa. The city was sacked and destroyed by Umayyad forces after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire.[3] It remained occupied during the Muslim period[4] and was used as a fort by the Muslims until the Hafsid period when it was taken by the Crusaders with its inhabitants massacred during the Eighth Crusade. The Hafsids decided to destroy its defenses so it could not be used as a base by a hostile power again.[5] It also continued to function as an episcopal see.

The regional power had shifted to Kairouan and the Medina of Tunis in the medieval period, until the early 20th century, when it began to develop into a coastal suburb of Tunis, incorporated as Carthage municipality in 1919. The archaeological site was first surveyed in 1830, by Danish consul Christian Tuxen Falbe. Excavations were performed in the second half of the 19th century by Charles Ernest Beulé and by Alfred Louis Delattre. The Carthage National Museum was founded in 1875 by Cardinal Charles Lavigerie. Excavations performed by French archaeologists in the 1920s first attracted an extraordinary amount of attention because of the evidence they produced for child sacrifice. There has been considerable disagreement among scholars concerning whether child sacrifice was practiced by ancient Carthage.[6][7] The open-air Carthage Paleo-Christian Museum has exhibits excavated under the auspices of UNESCO from 1975 to 1984.

Name

The name Carthage /ˈkɑːrθɪdʒ/ is the Early Modern anglicisation of Middle French Carthage /kar.taʒ/,[8] from Latin Carthāgō and Karthāgō (cf. Greek Karkhēdōn (Καρχηδών) and Etruscan *Carθaza) from the Punic qrt-ḥdšt (𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕) "new city",[9] implying it was a "new Tyre".[10] The Latin adjective pūnicus, meaning "Phoenician", is reflected in English in some borrowings from Latin—notably the Punic Wars and the Punic language.

The Modern Standard Arabic form قرطاج (![]()

Topography, layout and society

Overview

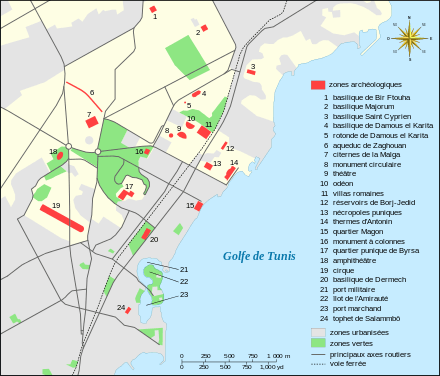

Carthage was built on a promontory with sea inlets to the north and the south. The city's location made it master of the Mediterranean's maritime trade. All ships crossing the sea had to pass between Sicily and the coast of Tunisia, where Carthage was built, affording it great power and influence. Two large, artificial harbors were built within the city, one for harboring the city's massive navy of 220 warships and the other for mercantile trade. A walled tower overlooked both harbors. The city had massive walls, 37 km (23 mi) long, which was longer than the walls of comparable cities. Most of the walls were on the shore and so could be less impressive, as Carthaginian control of the sea made attack from that direction difficult. The 4.0 to 4.8 km (2.5 to 3 mi) of wall on the isthmus to the west were truly massive and were never penetrated.

Carthage was one of the largest cities of the Hellenistic period and was among the largest cities in preindustrial history. Whereas by AD 14, Rome had at least 750,000 inhabitants and in the following century may have reached 1 million, the cities of Alexandria and Antioch numbered only a few hundred thousand or less.[12] According to the not-always-reliable history of Herodian, Carthage rivaled Alexandria for second place in the Roman empire.[13]

Layout

The Punic Carthage was divided into four equally sized residential areas with the same layout, had religious areas, market places, council house, towers, a theater, and a huge necropolis; roughly in the middle of the city stood a high citadel called the Byrsa. Surrounding Carthage were walls "of great strength" said in places to rise above 13 m, being nearly 10 m thick, according to ancient authors. To the west, three parallel walls were built. The walls altogether ran for about 33 kilometres (21 miles) to encircle the city.[14][15] The heights of the Byrsa were additionally fortified; this area being the last to succumb to the Romans in 146 BC. Originally the Romans had landed their army on the strip of land extending southward from the city.[16][17]

Outside the city walls of Carthage is the Chora or farm lands of Carthage. Chora encompassed a limited area: the north coastal tell, the lower Bagradas river valley (inland from Utica), Cape Bon, and the adjacent sahel on the east coast. Punic culture here achieved the introduction of agricultural sciences first developed for lands of the eastern Mediterranean, and their adaptation to local African conditions.[18]

The urban landscape of Carthage is known in part from ancient authors,[19] augmented by modern digs and surveys conducted by archeologists. The "first urban nucleus" dating to the seventh century, in area about 10 hectares (25 acres), was apparently located on low-lying lands along the coast (north of the later harbors). As confirmed by archaeological excavations, Carthage was a "creation ex nihilo", built on 'virgin' land, and situated at what was then the end of a peninsula. Here among "mud brick walls and beaten clay floors" (recently uncovered) were also found extensive cemeteries, which yielded evocative grave goods like clay masks. "Thanks to this burial archaeology we know more about archaic Carthage than about any other contemporary city in the western Mediterranean." Already in the eighth century, fabric dyeing operations had been established, evident from crushed shells of murex (from which the 'Phoenician purple' was derived). Nonetheless, only a "meager picture" of the cultural life of the earliest pioneers in the city can be conjectured, and not much about housing, monuments or defenses.[20][21] The Roman poet Virgil (70–19 BC) imagined early Carthage, when his legendary character Aeneas had arrived there:

"Aeneas found, where lately huts had been,

marvelous buildings, gateways, cobbled ways,

and din of wagons. There the Tyrians

were hard at work: laying courses for walls,

rolling up stones to build the citadel,

while others picked out building sites and plowed

a boundary furrow. Laws were being enacted,

magistrates and a sacred senate chosen.

Here men were dredging harbors, there they laid

the deep foundations of a theatre,

and quarried massive pillars... ."[22][23]

The two inner harbours, named cothon in Punic, were located in the southeast; one being commercial, and the other for war. Their definite functions are not entirely known, probably for the construction, outfitting, or repair of ships, perhaps also loading and unloading cargo.[24][25][26] Larger anchorages existed to the north and south of the city.[27] North and west of the cothon were located several industrial areas, e.g., metalworking and pottery (e.g., for amphora), which could serve both inner harbours, and ships anchored to the south of the city.[28]

About the Byrsa, the citadel area to the north,[29] considering its importance our knowledge of it is patchy. Its prominent heights were the scene of fierce combat during the fiery destruction of the city in 146 BC. The Byrsa was the reported site of the Temple of Eshmun (the healing god), at the top of a stairway of sixty steps.[30][31] A temple of Tanit (the city's queen goddess) was likely situated on the slope of the 'lesser Byrsa' immediately to the east, which runs down toward the sea.[32] Also situated on the Byrsa were luxury homes.[33]

South of the citadel, near the cothon was the tophet, a special and very old cemetery, which when begun lay outside the city's boundaries. Here the Salammbô was located, the Sanctuary of Tanit, not a temple but an enclosure for placing stone stelae. These were mostly short and upright, carved for funeral purposes. The presence of infant skeletons from here may indicate the occurrence of child sacrifice, as claimed in the Bible, although there has been considerable doubt among archeologists as to this interpretation and many consider it simply a cemetery devoted to infants.[34] Probably the tophet burial fields were "dedicated at an early date, perhaps by the first settlers."[35][36] Recent studies, on the other hand, indicate that child sacrifice was practiced by the Carthaginians.[37][38]

Between the sea-filled cothon for shipping and the Byrsa heights lay the agora [Greek: "market"], the city-state's central marketplace for business and commerce. The agora was also an area of public squares and plazas, where the people might formally assemble, or gather for festivals. It was the site of religious shrines, and the location of whatever were the major municipal buildings of Carthage. Here beat the heart of civic life. In this district of Carthage, more probably, the ruling suffets presided, the council of elders convened, the tribunal of the 104 met, and justice was dispensed at trials in the open air.[39][40]

Early residential districts wrapped around the Byrsa from the south to the north east. Houses usually were whitewashed and blank to the street, but within were courtyards open to the sky.[41] In these neighborhoods multistory construction later became common, some up to six stories tall according to an ancient Greek author.[42][43] Several architectural floorplans of homes have been revealed by recent excavations, as well as the general layout of several city blocks. Stone stairs were set in the streets, and drainage was planned, e.g., in the form of soakways leaching into the sandy soil.[44] Along the Byrsa's southern slope were located not only fine old homes, but also many of the earliest grave-sites, juxtaposed in small areas, interspersed with daily life.[45]

Artisan workshops were located in the city at sites north and west of the harbours. The location of three metal workshops (implied from iron slag and other vestiges of such activity) were found adjacent to the naval and commercial harbours, and another two were further up the hill toward the Byrsa citadel. Sites of pottery kilns have been identified, between the agora and the harbours, and further north. Earthenware often used Greek models. A fuller's shop for preparing woolen cloth (shrink and thicken) was evidently situated further to the west and south, then by the edge of the city.[46] Carthage also produced objects of rare refinement. During the 4th and 3rd centuries, the sculptures of the sarcophagi became works of art. "Bronze engraving and stone-carving reached their zenith."[47]

The elevation of the land at the promontory on the seashore to the north-east (now called Sidi Bou Saïd), was twice as high above sea level as that at the Byrsa (100 m and 50 m). In between runs a ridge, several times reaching 50 m; it continues northwestward along the seashore, and forms the edge of a plateau-like area between the Byrsa and the sea.[48] Newer urban developments lay here in these northern districts.[49]

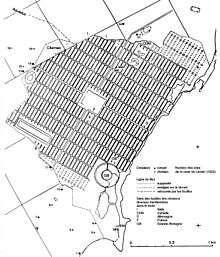

Due to the Roman's leveling of the city, the original Punic urban landscape of Carthage was largely lost. Since 1982, French archaeologist Serge Lancel excavated a residential area of the Punic Carthage on top of Byrsa hill near the Forum of the Roman Carthage. The neighborhood can be dated back to early second century BC, and with its houses, shops, and private spaces, is significant for what it reveals about daily life of the Punic Carthage.[50]

The remains have been preserved under embankments, the substructures of the later Roman forum, whose foundation piles dot the district. The housing blocks are separated by a grid of straight streets about 6 m (20 ft) wide, with a roadway consisting of clay; in situ stairs compensate for the slope of the hill. Construction of this type presupposes organization and political will, and has inspired the name of the neighborhood, "Hannibal district", referring to the legendary Punic general or sufet (consul) at the beginning of the second century BC. The habitat is typical, even stereotypical. The street was often used as a storefront/shopfront; cisterns were installed in basements to collect water for domestic use, and a long corridor on the right side of each residence led to a courtyard containing a sump, around which various other elements may be found. In some places, the ground is covered with mosaics called punica pavement, sometimes using a characteristic red mortar.

Society and Local Economy

Punic culture and agricultural sciences, when arrived at Carthage from eastern Mediterranean, gradually adapted to the local African conditions. The merchant harbor at Carthage was developed after settlement of the nearby Punic town of Utica, and eventually the surrounding African countryside was brought into the orbit of the Punic urban centers, first commercially, then politically. Direct management over cultivation of neighbouring lands by Punic owners followed.[51] A 28-volume work on agriculture written in Punic by Mago, a retired army general (c. 300), was translated into Latin and later into Greek. The original and both translations have been lost; however, some of Mago's text has survived in other Latin works.[52] Olive trees (e.g., grafting), fruit trees (pomegranate, almond, fig, date palm), viniculture, bees, cattle, sheep, poultry, implements, and farm management were among the ancient topics which Mago discussed. As well, Mago addresses the wine-maker's art (here a type of sherry).[53][54][55]

In Punic farming society, according to Mago, the small estate owners were the chief producers. They were, two modern historians write, not absent landlords. Rather, the likely reader of Mago was "the master of a relatively modest estate, from which, by great personal exertion, he extracted the maximum yield." Mago counselled the rural landowner, for the sake of their own 'utilitarian' interests, to treat carefully and well their managers and farm workers, or their overseers and slaves.[56] Yet elsewhere these writers suggest that rural land ownership provided also a new power base among the city's nobility, for those resident in their country villas.[57][58] By many, farming was viewed as an alternative endeavour to an urban business. Another modern historian opines that more often it was the urban merchant of Carthage who owned rural farming land to some profit, and also to retire there during the heat of summer.[59] It may seem that Mago anticipated such an opinion, and instead issued this contrary advice (as quoted by the Roman writer Columella):

The man who acquires an estate must sell his house, lest he prefer to live in the town rather than in the country. Anyone who prefers to live in a town has no need of an estate in the country."[60] "One who has bought land should sell his town house, so that he will have no desire to worship the household gods of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes greater delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate.[61]

The issues involved in rural land management also reveal underlying features of Punic society, its structure and stratification. The hired workers might be considered 'rural proletariat', drawn from the local Berbers. Whether there remained Berber landowners next to Punic-run farms is unclear. Some Berbers became sharecroppers. Slaves acquired for farm work were often prisoners of war. In lands outside Punic political control, independent Berbers cultivated grain and raised horses on their lands. Yet within the Punic domain that surrounded the city-state of Carthage, there were ethnic divisions in addition to the usual quasi feudal distinctions between lord and peasant, or master and serf. This inherent instability in the countryside drew the unwanted attention of potential invaders.[62] Yet for long periods Carthage was able to manage these social difficulties.[63]

The many amphorae with Punic markings subsequently found about ancient Mediterranean coastal settlements testify to Carthaginian trade in locally made olive oil and wine.[64] Carthage's agricultural production was held in high regard by the ancients, and rivaled that of Rome—they were once competitors, e.g., over their olive harvests. Under Roman rule, however, grain production ([wheat] and barley) for export increased dramatically in 'Africa'; yet these later fell with the rise in Roman Egypt's grain exports. Thereafter olive groves and vineyards were re-established around Carthage. Visitors to the several growing regions that surrounded the city wrote admiringly of the lush green gardens, orchards, fields, irrigation channels, hedgerows (as boundaries), as well as the many prosperous farming towns located across the rural landscape.[65][66]

Accordingly, the Greek author and compiler Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC), who enjoyed access to ancient writings later lost, and on which he based most of his writings, described agricultural land near the city of Carthage circa 310 BC:

It was divided into market gardens and orchards of all sorts of fruit trees, with many streams of water flowing in channels irrigating every part. There were country homes everywhere, lavishly built and covered with stucco. ... Part of the land was planted with vines, part with olives and other productive trees. Beyond these, cattle and sheep were pastured on the plains, and there were meadows with grazing horses.[67][68]

Ancient history

Greek cities contested with Carthage for the Western Mediterranean culminating in the Sicilian Wars and the Pyrrhic War over Sicily, while the Romans fought three wars against Carthage, known as the Punic Wars,[69][70] "Punic" meaning "Phoenician" in Latin, as Carthage was a Phoenician colony grown into a kingdom.

Punic Republic

The Carthaginian republic was one of the longest-lived and largest states in the ancient Mediterranean. Reports relay several wars with Syracuse and finally, Rome, which eventually resulted in the defeat and destruction of Carthage in the Third Punic War. The Carthaginians were Phoenician settlers originating in the Mediterranean coast of the Near East. They spoke Canaanite, a Semitic language, and followed a local variety of the ancient Canaanite religion.

The fall of Carthage came at the end of the Third Punic War in 146 BC at the Battle of Carthage.[71] Despite initial devastating Roman naval losses and Rome's recovery from the brink of defeat after the terror of a 15-year occupation of much of Italy by Hannibal, the end of the series of wars resulted in the end of Carthaginian power and the complete destruction of the city by Scipio Aemilianus. The Romans pulled the Phoenician warships out into the harbor and burned them before the city, and went from house to house, capturing and enslaving the people. About 50,000 Carthaginians were sold into slavery.[72] The city was set ablaze and razed to the ground, leaving only ruins and rubble. After the fall of Carthage, Rome annexed the majority of the Carthaginian colonies, including other North African locations such as Volubilis, Lixus, Chellah.[73]

The legend that the city was sown with salt remains widely accepted despite a lack of evidence among ancient historical accounts;[74] According to R.T. Ridley, the earliest such claim is attributable to B.L. Hallward's chapter in Cambridge Ancient History, published in 1930. Ridley contended that Hallward's claim may have gained traction due to historical evidence of other salted-earth instances such as Abimelech's salting of Shechem in Judges 9:45.[75][76] B.H. Warmington admitted he had repeated Hallward's error, but posited that the legend precedes 1930 and inspired repetitions of the practice. He also suggested that it is useful to understand how subsequent historical narratives have been framed and that the symbolic value of the legend is so great and enduring that it mitigates a deficiency of concrete evidence.[74]

For many years but especially beginning in the 19th century,[77] various texts claim that after defeating the city of Carthage in the Third Punic War (146 BC), the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus Africanus ordered the city be sacked, forced its surviving inhabitants into slavery, plowed it over and sowed it with salt. However, no ancient sources exist documenting the salting itself. The element of salting is therefore probably a later invention modeled on the Biblical story of Shechem.[78] The ritual of symbolically drawing a plow over the site of a city is mentioned in ancient sources, but not in reference to Carthage specifically.[79] When Pope Boniface VIII destroyed Palestrina in 1299, he issued a papal bull that it be plowed "following the old example of Carthage in Africa" and also salted.[80] "I have run the plough over it, like the ancient Carthage of Africa, and I have had salt sown upon it...."[81]

Roman Carthage

When Carthage fell, its nearby rival Utica, a Roman ally, was made capital of the region and replaced Carthage as the leading center of Punic trade and leadership. It had the advantageous position of being situated on the outlet of the Medjerda River, Tunisia's only river that flowed all year long. However, grain cultivation in the Tunisian mountains caused large amounts of silt to erode into the river. This silt accumulated in the harbor until it became useless, and Rome was forced to rebuild Carthage.

By 122 BC, Gaius Gracchus founded a short-lived colony, called Colonia Iunonia, after the Latin name for the Punic goddess Tanit, Iuno Caelestis. The purpose was to obtain arable lands for impoverished farmers. The Senate abolished the colony some time later, to undermine Gracchus' power.

After this ill-fated attempt, a new city of Carthage was built on the same land by Julius Caesar in the period from 49 to 44 BC, and by the first century, it had grown to be the second-largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire, with a peak population of 500,000.[82] It was the center of the province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the Empire. Among its major monuments was an amphitheater.

Carthage also became a center of early Christianity (see Carthage (episcopal see)). In the first of a string of rather poorly reported councils at Carthage a few years later, no fewer than 70 bishops attended. Tertullian later broke with the mainstream that was increasingly represented in the West by the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, which Augustine of Hippo spent much time and parchment arguing against. At the Council of Carthage (397), the biblical canon for the western Church was confirmed. The Christians at Carthage conducted persecutions against the pagans, during which the pagan temples, notably the famous Temple of Juno Caelesti, were destroyed.[83]

The political fallout from the deep disaffection of African Christians is supposedly a crucial factor in the ease with which Carthage and the other centers were captured in the fifth century by Gaiseric, king of the Vandals, who defeated the Roman general Bonifacius and made the city the capital of the Vandal Kingdom. Gaiseric was considered a heretic, too, an Arian, and though Arians commonly despised Catholic Christians, a mere promise of toleration might have caused the city's population to accept him.

The Vandals during their conquest are said to have destroyed parts of Carthage by Victor Vitensis in Historia Persecutionis Africanae Provincia including various buildings and churches.[84]

After a failed attempt to recapture the city in the fifth century, the Eastern Roman Empire finally subdued the Vandals in the Vandalic War in 533–534. Thereafter, the city became the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa, which was made into an exarchate during the emperor Maurice's reign, as was Ravenna on the Italian Peninsula. These two exarchates were the western bulwarks of the Byzantine Empire, all that remained of its power in the West. In the early seventh century Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Carthage, overthrew the Byzantine emperor Phocas, whereupon his son Heraclius succeeded to the imperial throne.

Islamic period

The Roman Exarchate of Africa was not able to withstand the seventh-century Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. The Umayyad Caliphate under Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan in 686 sent a force led by Zuhayr ibn Qays, who won a battle over the Romans and Berbers led by King Kusaila of the Kingdom of Altava on the plain of Kairouan, but he could not follow that up. In 695, Hassan ibn al-Nu'man captured Carthage and advanced into the Atlas Mountains. An imperial fleet arrived and retook Carthage, but in 698, Hasan ibn al-Nu'man returned and defeated Emperor Tiberios III at the 698 Battle of Carthage. Roman imperial forces withdrew from all of Africa except Ceuta. Fearing that the Byzantine Empire might reconquer it, they decided to destroy Roman Carthage in a scorched earth policy and establish their headquarters somewhere else. Its walls were torn down, the water supply from its aqueducts cut off, the agricultural land was ravaged and its harbors made unusable.[3]

The destruction of the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to the Byzantine Empire's influence in the region.

It is visible from archaeological evidence, that the town of Carthage continued to be occupied. The neighborhood of Bjordi Djedid continued to be occupied. The Baths of Antoninus continued to function in the Arab period and the historian Al-Bakri stated that they were still in good condition. They also had production centers nearby. It is difficult to determine whether the continued habitation of some other buildings belonged to Late Byzantine or Early Arab period. The Bir Ftouha church might have continued to remain in use though it is not clear when it became uninhabited.[4] Constantine the African was born in Carthage.[85]

The Medina of Tunis, originally a Berber settlement, was established as the new regional center under the Umayyad Caliphate in the early 8th century. Under the Aghlabids, the people of Tunis revolted numerous times, but the city profited from economic improvements and quickly became the second most important in the kingdom. It was briefly the national capital, from the end of the reign of Ibrahim II in 902, until 909, when the Shi'ite Berbers took over Ifriqiya and founded the Fatimid Caliphate.

Carthage remained a residential see until the high medieval period, mentioned in two letters of Pope Leo IX dated 1053,[86] written in reply to consultations regarding a conflict between the bishops of Carthage and Gummi. In each of the two letters, Pope Leo declares that, after the Bishop of Rome, the first archbishop and chief metropolitan of the whole of Africa is the bishop of Carthage. Later, an archbishop of Carthage named Cyriacus was imprisoned by the Arab rulers because of an accusation by some Christians. Pope Gregory VII wrote him a letter of consolation, repeating the hopeful assurances of the primacy of the Church of Carthage, "whether the Church of Carthage should still lie desolate or rise again in glory". By 1076, Cyriacus was set free, but there was only one other bishop in the province. These are the last of whom there is mention in that period of the history of the see.[87][88]

The fortress of Carthage was used by the Muslims until Hafsid era and was captured by the Crusaders during the Eighth Crusade. The inhabitants of Carthage were slaughtered by the Crusaders after they took it, and it was used as a base of operations against the Hafsids. After repelling them, Muhammad I al-Mustansir decided to destroy Cathage's defenses completely to prevent a repeat.[5]

Modern history

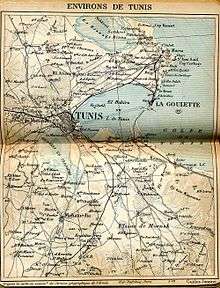

Carthage is some 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) east-northeast of Tunis; the settlements nearest to Carthage were the town of Sidi Bou Said to the north and the village of Le Kram to the south. Sidi Bou Said was a village which had grown around the tomb of the eponymous sufi saint (d. 1231), which had been developed into a town under Ottoman rule in the 18th century. Le Kram was developed in the late 19th century under French administration as a settlement close to the port of La Goulette.

In 1881, Tunisia became a French protectorate, and in the same year Charles Lavigerie, who was archbishop of Algiers, became apostolic administrator of the vicariate of Tunis. In the following year, Lavigerie became a cardinal. He "saw himself as the reviver of the ancient Christian Church of Africa, the Church of Cyprian of Carthage",[89] and, on 10 November 1884, was successful in his great ambition of having the metropolitan see of Carthage restored, with himself as its first archbishop.[90] In line with the declaration of Pope Leo IX in 1053, Pope Leo XIII acknowledged the revived Archdiocese of Carthage as the primatial see of Africa and Lavigerie as primate.[91][92]

The Acropolium of Carthage (Saint Louis Cathedral of Carthage) was erected on Byrsa hill in 1884.

Archaeological site

The Danish consul Christian Tuxen Falbe conducted a first survey of the topography of the archaeological site (published in 1833). Antiquarian interest was intensified following the publication of Flaubert's Salammbô in 1858. Charles Ernest Beulé performed some preliminary excavations of Roman remains on Byrsa hill in 1860.[93] A more systematic survey of both Punic and Roman-era remains is due to Alfred Louis Delattre, who was sent to Tunis by cardinal Charles Lavigerie in 1875 on both an apostolic and an archaeological mission.[94] Audollent (1901, p. 203) cites Delattre and Lavigerie to the effect that in the 1880s, locals still knew the area of the ancient city under the name of Cartagenna (i.e. reflecting the Latin n-stem Carthāgine).

Auguste Audollent divides the area of Roman Carthage into four quarters, Cartagenna, Dermèche, Byrsa and La Malga. Cartagenna and Dermèche correspond with the lower city, including the site of Punic Carthage; Byrsa is associated with the upper city, which in Punic times was a walled citadel above the harbour; and La Malga is linked with the more remote parts of the upper city in Roman times.

French-led excavations at Carthage began in 1921, and from 1923 reported finds of a large quantity of urns containing a mixture of animal and children's bones. René Dussaud identified a 4th-century BC stela found in Carthage as depicting a child sacrifice.[95]

A temple at Amman (1400–1250 BC) excavated and reported upon by J.B. Hennessy in 1966, shows the possibility of bestial and human sacrifice by fire. While evidence of child sacrifice in Canaan was the object of academic disagreement, with some scholars arguing that merely children's cemeteries had been unearthed in Carthage, the mixture of children's with animal bones as well as associated epigraphic evidence involving mention of mlk led some to believe that, at least in Carthage, child sacrifice was indeed common practice.[96] However, though the animals were surely sacrificed, this does not entirely indicate that the infants were, and in fact the bones indicate the opposite. Rather, the animal sacrifice was likely done to, in some way, honour the deceased.[97]

In 2016, an ancient Carthaginian individual, who was excavated from a Punic tomb in Byrsa Hill, was found to belong to the rare U5b2c1 maternal haplogroup. The Young Man of Byrsa specimen dates from the late 6th century BCE, and his lineage is believed to represent early gene flow from Iberia to the Maghreb.[98]

Commune

In 1920, the first seaplane base was built on the Lake of Tunis for the seaplanes of Compagnie Aéronavale.[99] The Tunis Airfield opened in 1938, serving around 5,800 passengers annually on the Paris-Tunis route.[100] During World War II, the airport was used by the United States Army Air Force Twelfth Air Force as a headquarters and command control base for the Italian Campaign of 1943. Construction on the Tunis-Carthage Airport, which was fully funded by France, began in 1944, and in 1948 the airport become the main hub for Tunisair.

In the 1950s the Lycée Français de Carthage was established to serve French families in Carthage. In 1961 it was given to the Tunisian government as part of the Independence of Tunisia, so the nearby Collège Maurice Cailloux in La Marsa, previously an annex of the Lycée Français de Carthage, was renamed to the Lycée Français de La Marsa and began serving the lycée level. It is currently the Lycée Gustave Flaubert.[101]

After Tunisian independence in 1956, the Tunis conurbation gradually extended around the airport, and Carthage (قرطاج Qarṭāj) is now a suburb of Tunis, covering the area between Sidi Bou Said and Le Kram.[102][103] Its population as of January 2013 was estimated at 21,276,[104] mostly attracting the more wealthy residents.[105] If Carthage is not the capital, it tends to be the political pole, a « place of emblematic power » according to Sophie Bessis,[106] leaving to Tunis the economic and administrative roles. The Carthage Palace (the Tunisian presidential palace) is located in the coast.[107]

The suburb has six train stations of the TGM line between Le Kram and Sidi Bou Said: Carthage Salammbo (named for Salambo, the fictional daughter of Hamilcar), Carthage Byrsa (named for Byrsa hill), Carthage Dermech (Dermèche), Carthage Hannibal (named for Hannibal), Carthage Présidence (named for the Presidential Palace) and Carthage Amilcar (named for Hamilcar).

In literature

The scant remains of what was once a great city are reflected upon in Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poem, Carthage, published in 1836 with quotes from Sir Grenville Temple's Journal.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Trade and business

The merchants of Carthage were in part heirs of the Mediterranean trade developed by Phoenicia, and so also heirs of the rivalry with Greek merchants. Business activity was accordingly both stimulated and challenged. Cyprus had been an early site of such commercial contests. The Phoenicians then had ventured into the western Mediterranean, founding trading posts, including Utica and Carthage. The Greeks followed, entering the western seas where the commercial rivalry continued. Eventually it would lead, especially in Sicily, to several centuries of intermittent war.[108][109] Although Greek-made merchandise was generally considered superior in design, Carthage also produced trade goods in abundance. That Carthage came to function as a manufacturing colossus was shown during the Third Punic War with Rome. Carthage, which had previously disarmed, then was made to face the fatal Roman siege. The city "suddenly organised the manufacture of arms" with great skill and effectiveness. According to Strabo (63 BC – AD 21) in his Geographica:

[Carthage] each day produced one hundred and forty finished shields, three hundred swords, five hundred spears, and one thousand missiles for the catapults... . Furthermore, [Carthage although surrounded by the Romans] built one hundred and twenty decked ships in two months... for old timber had been stored away in readiness, and a large number of skilled workmen, maintained at public expense.[110]

The textiles industry in Carthage probably started in private homes, but the existence of professional weavers indicates that a sort of factory system later developed. Products included embroidery, carpets, and use of the purple murex dye (for which the Carthaginian isle of Djerba was famous). Metalworkers developed specialized skills, i.e., making various weapons for the armed forces, as well as domestic articles, such as knives, forks, scissors, mirrors, and razors (all articles found in tombs). Artwork in metals included vases and lamps in bronze, also bowls, and plates. Other products came from such crafts as the potters, the glassmakers, and the goldsmiths. Inscriptions on votive stele indicate that many were not slaves but 'free citizens'.[111]

Phoenician and Punic merchant ventures were often run as a family enterprise, putting to work its members and its subordinate clients. Such family-run businesses might perform a variety of tasks: own and maintain the ships, providing the captain and crew; do the negotiations overseas, either by barter or buying and selling, of their own manufactured commodities and trade goods, and native products (metals, foodstuffs, etc.) to carry and trade elsewhere; and send their agents to stay at distant outposts in order to make lasting local contacts, and later to establish a warehouse of shipped goods for exchange, and eventually perhaps a settlement. Over generations, such activity might result in the creation of a wide-ranging network of trading operations. Ancillary would be the growth of reciprocity between different family firms, foreign and domestic.[112][113]

State protection was extended to its sea traders by the Phoenician city of Tyre and later likewise by the daughter city-state of Carthage.[114] Stéphane Gsell, the well-regarded French historian of ancient North Africa, summarized the major principles guiding the civic rulers of Carthage with regard to its policies for trade and commerce:

- to open and maintain markets for its merchants, whether by entering into direct contact with foreign peoples using either treaty negotiations or naval power, or by providing security for isolated trading stations

- the reservation of markets exclusively for the merchants of Carthage, or where competition could not be eliminated, to regulate trade by state-sponsored agreements with its commercial rivals

- suppression of piracy, and promotion of Carthage's ability to freely navigate the seas[115]

Both the Phoenicians and the Cathaginians were well known in antiquity for their secrecy in general, and especially pertaining to commercial contacts and trade routes.[116][117][118] Both cultures excelled in commercial dealings. Strabo (63BC-AD21) the Greek geographer wrote that before its fall (in 146 BC) Carthage enjoyed a population of 700,000, and directed an alliance of 300 cities.[119] The Greek historian Polybius (c.203–120) referred to Carthage as "the wealthiest city in the world".[120]

Constitution of state

A "suffet" (possibly two) was elected by the citizens, and held office with no military power for a one-year term. Carthaginian generals marshalled mercenary armies and were separately elected. From about 550 to 450 the Magonid family monopolized the top military position; later the Barcid family acted similarly. Eventually it came to be that, after a war, the commanding general had to testify justifying his actions before a court of 104 judges.[121]

Aristotle (384–322) discusses Carthage in his work, Politica; he begins: "The Carthaginians are also considered to have an excellent form of government." He briefly describes the city as a "mixed constitution", a political arrangement with cohabiting elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, i.e., a king (Gk: basileus), a council of elders (Gk: gerusia), and the people (Gk: demos).[122] Later Polybius of Megalopolis (c.204–122, Greek) in his Histories would describe the Roman Republic in more detail as a mixed constitution in which the Consuls were the monarchy, the Senate the aristocracy, and the Assemblies the democracy.[123]

Evidently Carthage also had an institution of elders who advised the Suffets, similar to a Greek gerusia or the Roman Senate. We do not have a Punic name for this body. At times its members would travel with an army general on campaign. Members also formed permanent committees. The institution had several hundred members drawn from the wealthiest class who held office for life. Vacancies were probably filled by recruitment from among the elite, i.e., by co-option. From among its members were selected the 104 Judges mentioned above. Later the 104 would come to evaluate not only army generals but other office holders as well. Aristotle regarded the 104 as most important; he compared it to the ephorate of Sparta with regard to control over security. In Hannibal's time, such a Judge held office for life. At some stage there also came to be independent self-perpetuating boards of five who filled vacancies and supervised (non-military) government administration.[124]

Popular assemblies also existed at Carthage. When deadlocked the Suffets and the quasi-senatorial institution of elders might request the assembly to vote; also, assembly votes were requested in very crucial matters in order to achieve political consensus and popular coherence. The assembly members had no legal wealth or birth qualification. How its members were selected is unknown, e.g., whether by festival group or urban ward or another method.[125][126][127]

The Greeks were favourably impressed by the constitution of Carthage; Aristotle had a separate study of it made which unfortunately is lost. In his Politica he states: "The government of Carthage is oligarchical, but they successfully escape the evils of oligarchy by enriching one portion of the people after another by sending them to their colonies." "[T]heir policy is to send some [poorer citizens] to their dependent towns, where they grow rich."[128][129] Yet Aristotle continues, "[I]f any misfortune occurred, and the bulk of the subjects revolted, there would be no way of restoring peace by legal means." Aristotle remarked also:

Many of the Carthaginian institutions are excellent. The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal to the constitution; the Carthaginians have never had any rebellion worth speaking of, and have never been under the rule of a tyrant.[130]

Here one may remember that the city-state of Carthage, who citizens were mainly Libyphoenicians (of Phoenician ancestry born in Africa), dominated and exploited an agricultural countryside composed mainly of native Berber sharecroppers and farmworkers, whose affiliations to Carthage were open to divergent possibilities. Beyond these more settled Berbers and the Punic farming towns and rural manors, lived the independent Berber tribes, who were mostly pastoralists.

In the brief, uneven review of government at Carthage found in his Politica Aristotle mentions several faults. Thus, "that the same person should hold many offices, which is a favorite practice among the Carthaginians." Aristotle disapproves, mentioning the flute-player and the shoemaker. Also, that "magistrates should be chosen not only for their merit but for their wealth." Aristotle's opinion is that focus on pursuit of wealth will lead to oligarchy and its evils.

[S]urely it is a bad thing that the greatest offices... should be bought. The law which allows this abuse makes wealth of more account than virtue, and the whole state becomes avaricious. For, whenever the chiefs of the state deem anything honorable, the other citizens are sure to follow their example; and, where virtue has not the first place, their aristocracy cannot be firmly established.[131]

In Carthage the people seemed politically satisfied and submissive, according to the historian Warmington. They in their assemblies only rarely exercised the few opportunities given them to assent to state decisions. Popular influence over government appears not to have been an issue at Carthage. Being a commercial republic fielding a mercenary army, the people were not conscripted for military service, an experience which can foster the feel for popular political action. But perhaps this misunderstands the society; perhaps the people, whose values were based on small-group loyalty, felt themselves sufficiently connected to their city's leadership by the very integrity of the person-to-person linkage within their social fabric. Carthage was very stable; there were few openings for tyrants. Only after defeat by Rome devastated Punic imperial ambitions did the people of Carthage seem to question their governance and to show interest in political reform.[132]

In 196, following the Second Punic War (218–201), Hannibal Barca, still greatly admired as a Barcid military leader, was elected suffet. When his reforms were blocked by a financial official about to become a judge for life, Hannibal rallied the populace against the 104 judges. He proposed a one-year term for the 104, as part of a major civic overhaul. Additionally, the reform included a restructuring of the city's revenues, and the fostering of trade and agriculture. The changes rather quickly resulted in a noticeable increase in prosperity. Yet his incorrigible political opponents cravenly went to Rome, to charge Hannibal with conspiracy, namely, plotting war against Rome in league with Antiochus the Hellenic ruler of Syria. Although the Roman Scipio Africanus resisted such manoeuvre, eventually intervention by Rome forced Hannibal to leave Carthage. Thus, corrupt city officials efficiently blocked Hannibal Barca in his efforts to reform the government of Carthage.[133][134]

Mago (6th century) was King of Carthage; the head of state, war leader, and religious figurehead. His family was considered to possess a sacred quality. Mago's office was somewhat similar to that of a pharaoh, but although kept in a family it was not hereditary, it was limited by legal consent. Picard, accordingly, believes that the council of elders and the popular assembly are late institutions. Carthage was founded by the king of Tyre who had a royal monopoly on this trading venture. Thus it was the royal authority stemming from this traditional source of power that the King of Carthage possessed. Later, as other Phoenician ship companies entered the trading region, and so associated with the city-state, the King of Carthage had to keep order among a rich variety of powerful merchants in their negotiations among themselves and over risky commerce across the Mediterranean. Under these circumstance, the office of king began to be transformed. Yet it was not until the aristocrats of Carthage became wealthy owners of agricultural lands in Africa that a council of elders was institutionalized at Carthage.[135]

Contemporary sources

Most ancient literature concerning Carthage comes from Greek and Roman sources as Carthage's own documents were destroyed by the Romans.[136][137] Apart from inscriptions, hardly any Punic literature has survived, and none in its own language and script.[138] A brief catalogue would include:[139]

- three short treaties with Rome (Latin translations);[140][141][142]

- several pages of Hanno the Navigator's log-book concerning his fifth century maritime exploration of the Atlantic coast of west Africa (Greek translation);[143]

- fragments quoted from Mago's fourth/third century 28-volume treatise on agriculture (Latin translations);[144][145]

- the Roman playwright Plautus (c. 250 – 184) in his Poenulus incorporates a few fictional speeches delivered in Punic, whose written lines are transcribed into Latin letters phonetically;[146][147]

- the thousands of inscriptions made in Punic script, thousands, but many extremely short, e.g., a dedication to a deity with the personal name(s) of the devotee(s).[148][149]

"[F]rom the Greek author Plutarch [(c. 46 – c. 120)] we learn of the 'sacred books' in Punic safeguarded by the city's temples. Few Punic texts survive, however."[150] Once "the City Archives, the Annals, and the scribal lists of suffets" existed, but evidently these were destroyed in the horrific fires during the Roman capture of the city in 146 BC.[151]

Yet some Punic books (Latin: libri punici) from the libraries of Carthage reportedly did survive the fires.[152] These works were apparently given by Roman authorities to the newly augmented Berber rulers.[153][154] Over a century after the fall of Carthage, the Roman politician-turned-author Gaius Sallustius Crispus or Sallust (86–34) reported his having seen volumes written in Punic, which books were said to be once possessed by the Berber king, Hiempsal II (r. 88–81).[155][156][157] By way of Berber informants and Punic translators, Sallust had used these surviving books to write his brief sketch of Berber affairs.[158][159]

Probably some of Hiempsal II's libri punici, that had escaped the fires that consumed Carthage in 146 BC, wound up later in the large royal library of his grandson Juba II (r.25 BC-AD 24).[160] Juba II not only was a Berber king, and husband of Cleopatra's daughter, but also a scholar and author in Greek of no less than nine works.[161] He wrote for the Mediterranean-wide audience then enjoying classical literature. The libri punici inherited from his grandfather surely became useful to him when composing his Libyka, a work on North Africa written in Greek. Unfortunately, only fragments of Libyka survive, mostly from quotations made by other ancient authors.[162] It may have been Juba II who 'discovered' the five-centuries-old 'log book' of Hanno the Navigator, called the Periplus, among library documents saved from fallen Carthage.[163][164][165]

In the end, however, most Punic writings that survived the destruction of Carthage "did not escape the immense wreckage in which so many of Antiquity's literary works perished."[166] Accordingly, the long and continuous interactions between Punic citizens of Carthage and the Berber communities that surrounded the city have no local historian. Their political arrangements and periodic crises, their economic and work life, the cultural ties and social relations established and nourished (infrequently as kin), are not known to us directly from ancient Punic authors in written accounts. Neither side has left us their stories about life in Punic-era Carthage.[167]

Regarding Phoenician writings, few remain and these seldom refer to Carthage. The more ancient and most informative are cuneiform tablets, ca. 1600–1185, from ancient Ugarit, located to the north of Phoenicia on the Syrian coast; it was a Canaanite city politically affiliated with the Hittites. The clay tablets tell of myths, epics, rituals, medical and administrative matters, and also correspondence.[168][169][170] The highly valued works of Sanchuniathon, an ancient priest of Beirut, who reportedly wrote on Phoenician religion and the origins of civilization, are themselves completely lost, but some little content endures twice removed.[171][172] Sanchuniathon was said to have lived in the 11th century, which is considered doubtful.[173][174] Much later a Phoenician History by Philo of Byblos (64–141) reportedly existed, written in Greek, but only fragments of this work survive.[175][176] An explanation proffered for why so few Phoenician works endured: early on (11th century) archives and records began to be kept on papyrus, which does not long survive in a moist coastal climate.[177] Also, both Phoenicians and Carthaginians were well known for their secrecy.[178][179]

Thus, of their ancient writings we have little of major interest left to us by Carthage, or by Phoenicia the country of origin of the city founders. "Of the various Phoenician and Punic compositions alluded to by the ancient classical authors, not a single work or even fragment has survived in its original idiom." "Indeed, not a single Phoenician manuscript has survived in the original [language] or in translation."[180] We cannot therefore access directly the line of thought or the contour of their worldview as expressed in their own words, in their own voice.[181] Ironically, it was the Phoenicians who "invented or at least perfected and transmitted a form of writing [the alphabet] that has influenced dozens of cultures including our own."[182][183][184]

As noted, the celebrated ancient books on agriculture written by Mago of Carthage survives only via quotations in Latin from several later Roman works.

References

- Hitchner, R.; R. Talbert; S. Gillies; J. Åhlfeldt; R. Warner; J. Becker; T. Elliott. "Places: 314921 (Carthago)". Pleiades. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- "F-LE Dido and the Foundation of Carthage". Illustrative Mathematics. Illustrative Mathematics. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2008). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Brill Academic Press. p. 536. ISBN 978-9004153882.

- Anna Leone (2007). Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. pp. 179–186. ISBN 9788872284988.

- Thomas F. Madden; James L. Naus; Vincent Ryan, eds. (2018). Crusades – Medieval Worlds in Conflict. pp. 113, 184. ISBN 9780198744320.

- Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants

- Ancient Carthaginians really did sacrifice their children. University of Oxford News

- c.f. Marlowes Dido, Queen of Carthage (c. 1590); Middle English still used the Latin form Carthago, e.g., John Trevisa, Polychronicon (1387) 1.169: That womman Dido that founded Carthago was comlynge.

- adjective qrt-ḥdty "Carthaginian"; compare Aramaic קרת חדתה, Qeret Ḥadatha, and Hebrew קרת חדשה, Qeret Ḥadašah. Wolfgang David Cirilo de Melo (ed), Amphitryon, Volume 4 of The Loeb Classical Library: Plautus, Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 210; D. Gary Miller, Ancient Greek Dialects and Early Authors: Introduction to the Dialect Mixture in Homer, with Notes on Lyric and Herodotus, Walter de Gruyter, 2014, p. 39.

- "Carthage: new excavations in a Mediterranean capital". ugent.be.

- Audollent (1901:203)

- Martin Percival Charlesworth; Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards; John Boardman; Frank William Walbank (2000). "Rome+was+larger" The Cambridge Ancient History: The fourth century B.C., 2nd ed., 1994. University Press. p. 813.

- Robert McQueen Grant (1 January 2004). Augustus to Constantine: The Rise and Triumph of Christianity in the Roman World. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-664-22772-2.

- Warmington, Carthage (1964) at 138–140, map at 139; at 273n.3, he cites the ancients: Appian, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, Polybius.

- Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963), text at 34, maps at 31 and 34. According to Harden, the outer walls ran several kilometres to the west of that indicated on the map here.

- Picard and Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 395–396.

- For an ample discussion of the ancient city: Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995, 1997) at 134–172, ancient harbours at 172–192; archaic Carthage at 38–77.

- Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 85 (limited area), at 88 (imported skills).

- e.g., the Greek writers: Appian, Diodorus Siculus, Polybius; and, the Latin: Livy, Strabo.

- Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992), as translated by A. Nevill (Oxford 1997), at 38–45 and 76–77 (archaic Carthage): maps of early city at 39 and 42; burial archaeology quote at 77; short quotes at 43, 38, 45, 39; clay masks at 60–62 (photographs); terracotta and ivory figurines at 64–66, 72–75 (photographs). Ancient coastline from Utica to Carthage: map at 18.

- Cf., B. H. Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; 2d ed. 1969) at 26–31.

- Virgil (70–19 BC), The Aeneid [19 BC], translated by Robert Fitzgerald [(New York: Random House 1983), p. 18–19 (Book I, 421–424). Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1997) p. 38. Here capitalized as prose.

- Virgil here, however, does innocently inject his own Roman cultural notions into his imagined description, e.g., Punic Carthage evidently built no theaters per se. Cf., Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968).

- The harbours, often mentioned by ancient authors, remain an archaeological problem due to the limited, fragmented evidence found. Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 172–192 (the two harbours).

- Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 32, 130–131.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 138.

- Sebkrit er Riana to the north, and El Bahira to the south [their modern names]. Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 31–32. Ships then could also be beached on the sand.

- Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 139–140, city map at 138.

- The lands immediately south of the hill is often also included by the term Byrsa.

- Serge Lancel, Carthage. A history (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 148–152; 151 and 149 map (leveling operations on the Byrsa, circa 25 BC, to prepare for new construction), 426 (Temple of Eshmun), 443 (Byrsa diagram, circa 1859). The Byrsa had been destroyed during the Third Punic War (149–146).

- Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (Paris 1958; London 1961, reprint Macmillan 1968) at 8 (city map showing the Temple of Eshmoun, on the eastern heights of the Byrsa).

- E. S. Bouchier, Life and Letters in Roman Africa (Oxford: B. H. Blackwell 1913) at 17, and 75. The Roman temple to Juno Caelestis is said to be later erected on the site of the ruined temple to Tanit.

- On the Byrsa some evidence remains of quality residential construction of 2nd century BC. Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 117.

- Jeffrey H. Schwartz, Frank Houghton, Roberto Macchiarelli, Luca Bondioli “Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants” http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0009177

- B. H. Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 15 (quote), 25, 141; (London: Robert Hale, 2d ed. 1969) at 27 (quote), 131–132, 133 (enclosure).

- See the section on Punic religion below.

- Xella, Paolo, et al. "Cemetery or sacrifice? Infant burials at the Carthage Tophet: Phoenician bones of contention." Antiquity 87.338 (2013): 1199-1207.

- Smith, Patricia, et al. "Cemetery or sacrifice? Infant burials at the Carthage Tophet: Age estimations attest to infant sacrifice at the Carthage Tophet." Antiquity 87.338 (2013): 1191-1199.

- Cf., Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 141.

- Modern archeologists on the site have not yet 'discovered' the ancient agora. Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 141.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 142.

- Appian of Alexandria (c.95 – c.160s), Pomaika known as the Roman History, at VII (Libyca), 128.

- Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 133 & 229n17 (Appian cited).

- Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 152–172, e.g., 163–165 (floorplans), 167–171 (neighborhood diagrams and photographs).

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 139 (map of city, re the tophet), 141.

- Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 138–140. These findings mostly relate to the 3rd century BC.

- Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris 1970; New York 1968) at 162–165 (carvings described), 176–178 (quote).

- Lancel, Carthage (1992; 1997) at 138 and 145 (city maps).

- This was especially so, later in the Roman era. E.g., Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 187–210.

- Serge Lancel and Jean-Paul Morel, "Byrsa. Punic vestiges"; To save Carthage. Exploration and conservation of the city Punic, Roman and Byzantine, Unesco / INAA, 1992, pp. 43–59

- Stéphanie Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord, volume four (Paris 1920).

- Serge Lancel, Carthage. A History (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 273–274 (Mago quoted by Columella), 278–279 (Mago and Cato's book), 358 (translations).

- Gilbert and Colette Picard, La vie quotidienne à Carthage au temps d'Hannibal (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1958), translated as Daily Life in Carthage (London: George Allen & Unwin 1961; reprint Macmillan, New York 1968) at 83–93: 88 (Mago as retired general), 89–91 (fruit trees), 90 (grafting), 89–90 (vineyards), 91–93 (livestock and bees), 148–149 (wine making). Elephants also, of course, were captured and reared for war (at 92).

- Sabatino Moscati, Il mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (London: Cardinal 1973) at 219–223. Hamilcar is named as another Carthaginian writing on agriculture (at 219).

- Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995), discussion of wine making and its 'marketing' at 273–276. Lancel says (at 274) that about wine making, Mago was silent. Punic agriculture and rural life are addressed at 269–302.

- G. and C. Charles-Picard, La vie quotidienne à Carthage au temps d'Hannibal (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1958) translated as Daily Life in Carthage (London: George Allen and Unwin 1961; reprint Macmillan 1968) at 83–93: 86 (quote); 86–87, 88, 93 (management); 88 (overseers).

- G. C. and C. Picard, Vie et mort de Carthage (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1970) translated (and first published) as The Life and Death of Carthage (New York: Taplinger 1968) at 86 and 129.

- Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 83–84: the development of a "landed nobility".

- B. H. Warmington, in his Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960; reprint Penguin 1964) at 155.

- Mago, quoted by Columella at I, i, 18; in Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 87, 101, n37.

- Mago, quoted by Columella at I, i, 18; in Moscati, The World of the Phoenicians (1966; 1973) at 220, 230, n5.

- Gilbert and Colette Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (1958; 1968) at 83–85 (invaders), 86–88 (rural proletariat).

- E.g., Gilbert Charles Picard and Colette Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris 1970; New York 1968) at 168–171, 172–173 (invasion of Agathocles in 310 BC). The mercenary revolt (240–237) following the First Punic War was also largely and actively, though unsuccessfully, supported by rural Berbers. Picard (1970; 1968) at 203–209.

- Plato (c. 427 – c. 347) in his Laws at 674, a-b, mentions regulations at Carthage restricting the consumption of wine in specified circumstances. Cf., Lancel, Carthage (1997) at 276.

- Warmington, Carthage (London: Robert Hale 1960, 2d ed. 1969) at 136–137.

- Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Arthème Fayard 1992) translated by Antonia Nevill (Oxford: Blackwell 1997) at 269–279: 274–277 (produce), 275–276 (amphora), 269–270 & 405 (Rome), 269–270 (yields), 270 & 277 (lands), 271–272 (towns).

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibleoteca, at XX, 8, 1–4, transl. as Library of History (Harvard University 1962), vol.10 [Loeb Classics, no.390); per Soren, Khader, Slim,, Carthage (1990) at 88.

- Lancel, Carthage (Paris 1992; Oxford 1997) at 277.

- Herodotus, V2. 165–7

- Polybius, World History: 1.7–1.60

- Pellechia, Thomas (2006). Wine: The 8,000-Year-Old Story of the Wine Trade. London: Running Press. ISBN 1-56025-871-3.

- "Ancient History". infoplease.com.

- C. Michael Hogan (2007) Volubilis, The Megalithic Portal, ed. by A. Burnham

- Warmington, B. H. (1988). "The Destruction of Carthage : A Retractatio". Classical Philology. 83 (4): 308–310. doi:10.1086/367123.

- Ridley, R. T. (1986). "To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 81 (2): 140–146. doi:10.1086/366973.

- George Ripley; Charles Anderson Dana (1863). The new American encyclopaedia: a popular dictionary of general knowledge. D. Appleton and company. p. 497.

- Ripley, George; Charles Anderson Dana (1863). The New American Cyclopædia: a Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. 4. p. 39.

- Ridley, 1986

- Stevens, 1988, p. 39-40.

- Warmington, 1988

- Sedgwick, Henry Dwight (2005). Italy In The Thirteenth Century, Part Two. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-4179-6638-7.

- Bridges That Babble On: 15 Amazing Roman Aqueducts, Article by Steve, filed under Abandoned Places in the Architecture category

- Brent D. Shaw: Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine

- Anna Leone (2007). Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. p. 155. ISBN 9788872284988.

- Singer, Charles (2013-10-29). A Short History of Science to the Nineteenth Century. ISBN 9780486169286.

- Patrologia Latina vol. 143, coll. 727–731

- Bouchier, E.S. (1913). Life and Letters in Roman Africa. Oxford: Blackwells. p. 117. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- François Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa(James Clarke & Co, 2011) p200.

- Hastings, Adrian (2004) [1994]. "The Victorian Missionary". The Church in Africa, 1450–1950. history of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 255. doi:10.1093/0198263996.003.0007. ISBN 9780198263999.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Joseph Sollier, "Charles-Martial-Allemand Lavigerie" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1910) Jenkins, Philip (2011). The next christendom : the coming of global Christianity (3rd ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780199767465.

-

- Charles Ernest Beulé, Fouilles à Carthage, éd. Imprimerie impériale, Paris, 1861.

- Azedine Beschaouch, La légende de Carthage, éd. Découvertes Gallimard, Paris, 1993, p. 94.

- Dussaud, Bulletin Archéologique (1922), p. 245.

- J.B. Hennessey, Palestine Exploration Quarterly (1966)

- Schwartz, Jeffery H.; Houghton, Frank; Macchiarelli, Roberto; Bondioli, Luca (2010-02-17). "Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants". Retrieved 2020-02-26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Matisoo-Smith EA, Gosling AL, Boocock J, Kardailsky O, Kurumilian Y, Roudesli-Chebbi S, et al. (May 25, 2016). "A European Mitochondrial Haplotype Identified in Ancient Phoenician Remains from Carthage, North Africa". PLoS ONE. 11 (5): e0155046. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155046M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155046. PMC 4880306. PMID 27224451.

- Philippe Bonnichon; Pierre Gény; Jean Nemo (2012). Présences françaises outre-mer, XVIe-XXIe siècles. KARTHALA Editions. p. 453. ISBN 978-2-8111-0737-6.

- Encyclopedie Mensuelle d'Outre-mer staff (1954). Tunisia 54. Negro Universities Press. p. 166.

- "Qui sommes nous ?" (Archive). Lycée Gustave Flaubert (La Marsa). Retrieved on February 24, 2016.

- Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (January 1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. Taylor & Francis. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-884964-03-9.

- Illustrated Encyclopaedia of World History. Mittal Publications. p. 1615. GGKEY:C6Z1Y8ZWS0N.

- "Statistical Information: Population". National Institute of Statistics – Tunisia. Retrieved 3 January 2014.; up from 15,922 in 2004 ("Population, ménages et logements par unité administrative" (in French). National Institute of Statistics – Tunisia. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2014.)

- David Lambert, Notables des colonies. Une élite de circonstance en Tunisie et au Maroc (1881–1939), éd. Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2009, pp. 257–258

- (in French) Sophie Bessis, « Défendre Carthage, encore et toujours », Le Courrier de l'Unesco, September 1999

- "More Tunisia unrest: Presidential palace gunbattle". philSTAR.com. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Cf., Charles-Picard, Daily Life in Carthage (Paris 195; Oxford 1961, reprint Macmillan 1968) at 165, 171–177.

- Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 57–62 (Cyprus and Aegean), 62–65 (western Mediterranean); 157–170 (trade); 67–70, 84–85, 160–164 (the Greeks).

- Strabo, Geographica, XVII,3,15; as translated by H. L. Jones (Loeb Classic Library 1932) at VIII: 385.

- Sabatino Moscati, The World of the Phoenicians (1966; 1973) at 223–224.

- Richard J. Harrison, Spain at the Dawn of History (London: Thames and Hudson 1988), "Phoenician colonies in Spain" at 41–50, 42.

- Cf., Harden, The Phoenicians (1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 157–166.

- E.g., during the reign of Hiram (tenth century) of Tyre. Sabatino Moscati, Il Mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (1968, 1973) at 31–34.

- Stéphane Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1924) at volume IV: 113.

- Strabo (c.63 B.C. – A.D. 20s), Geographica at III, 5.11.

- Walter W. Hyde, Ancient Greek Mariners (Oxford Univ. 1947) at 45–46.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 81 (secretive), 87 (monopolizing).

- Strabo, Geographica, XVII,3,15; in the Loeb Classic Library edition of 1932, translated by H. L. Jones, at VIII: 385.

- Cf., Theodor Mommsen, Römische Geschicht (Leipzig: Reimer and Hirzel 1854–1856), translated as the History of Rome (London 1862–1866; reprinted by J. M. Dent 1911) at II: 17–18 (Mommsen's Book III, Chapter I).

- Warmington, B. H. (1964) [1960]. Carthage. Robert Hale, Pelican. pp. 144–147.

- Aristotle, Politica at Book II, Chapter 11, (1272b–1274b); in The Basic Works of Aristotle edited by R. McKeon, translated by B. Jowett (Random House 1941), Politica at pages 1113–1316, "Carthage" at 1171–1174.

- Polybius, Histories VI, 11–18, translated as The Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin 1979) at 311–318.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 147–148.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 148.

- Aristotle presents a slightly more expansive interpretation of the role of assemblies. Politica II, 11, (1273a/6–11); McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1172.

- Compare Roman assemblies.

- Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/17–20), and at VI, 5, (1320b/4–6) re colonies; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, and at 1272.

- "Aristotle said that the oligarchy was careful to treat the masses liberally and allow them a share in the profitable exploitation of the subject territories." Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 149, citing Aristotle's Politica as here.

- Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/23–24) re misfortune and revolt, (1272b/29–32) re constitution and loyalty; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, 1171.

- Aristotle, Politica at II, 11, (1273b/8–16) re one person many offices, and (1273a/22–1273b/7) re oligarchy; in McKeon, ed., Basic Works of Aristotle (1941) at 1173, 1172–1273.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 143–144, 148–150. "The fact is that compared to Greeks and Romans the Carthaginians were essentially non-political." Ibid. at 149.

- H. H. Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753–146 BC (London: Methuen 1935, 4th ed. 1980; reprint Routledge 1991) at 306–307.

- Warmington, Carthage at 240–241, citing the Roman historian Livy.

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968) at 80–86

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 40–41 (Greeks), .

- Cf., Warmington, Carthage (1960; Penguin 1964) at 24–25 (Greeks), 259–260 (Romans).

- B.H.Warmington, "The Carthiginian Period" at 246–260, 246 ("No Carthaginian literature has survived."), in General History of Africa, volume III. Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990) Abridged Edition.

- R. Bosworth Smith, Carthage and the Carthaginians (London: Longmans, Green 1878, 1902) at 12. Smith's catalogue has not been appreciably augmented since, but for newly found inscriptions.

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 72–73: translation of Romano-Punic Treaty, 509 BC; at 72–78: discussion.

- Polybius (c. 200 – 118), Istorion at III, 22–25, selections translated as Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin 1979) at 199–203. Nota bene: Polybius died well over 70 years before the start of the Roman Empire.

- Cf., Arnold J. Toynbee, Hannibal's Legacy (1965) at I: 526, Appendix on the treaties.

- Hanno's log translated in full by Warmington, Carthage (1960) at 74–76.

- E.g., by Varro (116–27) in his De re rustica; by Columella (fl. AD 50–60) in his On trees and On agriculture, and by Pliny (23–79) in his Naturalis Historia. See below, paragraph on Mago's work.

- Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 122–123 (28 books), 140 (quotation of paragraph).

- Cf., H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Lanin Literature (London: Methuen 1930, 3d ed. 1954; reprint Dutton, New York 1960) at 51–52, where a plot summary of Poenulus (i.e., "The Man from Carthage") is given. Its main characters are Punic.

- Eighteen lines from Poenulus are spoken in Punic by the character Hanno in Act 5, scene 1, beginning "Hyth alonim vualonuth sicorathi si ma com sith... ." Plautus gives a Latin paraphrase in the next ten lines. The gist is a prayer seeking divine aid in his quest to find his lost kin. The Comedies of Plautus (London: G. Bell and Sons 1912), translated by Henry Thomas Riley. The scholar Bochart considered the first ten lines to be Punic, but the last eight to be 'Lybic'. Another scholar, Samuel Petit, translated the text as if it were Hebrew, a sister-language of Punic. This according to notes accompanying the above scene by H. T. Riley.

- Soren, Ben Khader, Slim, Carthage (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990) at 42 (over 6000 inscriptions found), at 139 (many very short, on religious stele).

- An example of a longer inscription (of about 279 Punic characters) exists at Thugga, Tunisia. It concerns the dedication of a temple to the late king Masinissa. A translated text appears in Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1997) at 39.

- Glenn E. Markoe, Carthage (2000) at 114.

- Picard and Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 30.

- Cf., Victor Matthews, "The libri punici of King Hiempsal" in American Journal of Philology 93: 330–335 (1972); and, Véronique Krings, "Les libri Punici de Sallust" in L'Africa Romana 7: 109–117 (1989). Cited by Roller (2003) at 27, n110.

- Pliny the Elder (23–79), Naturalis Historia at XVIII, 22–23.

- Serge Lancel, Carthage (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard 1992; Oxford: Blackwell 1995) at 358–360. Lancel here remarks that, following the fall of Carthage, there arose among the Romans there a popular reaction against the late Cato the Elder (234–149), the Roman censor who had notoriously lobbied for the destruction of the city. Lancel (1995) at 410.

- Ronald Syme, however, in his Sallust (University of California, 1964, 2002) at 152–153, discounts any unique value of the libri punici mentioned in his Bellum Iugurthinum.

- Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 359, raises questions concerning the provenance of these books.

- Hiempsal II was the great-grandson of Masinissa (r. 202–148), through Mastanabal (r. 148–140) and Gauda (r. 105–88). D. W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at 265.

- Sallust, Bellum Iugurthinum (ca. 42) at ¶17, translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963) at 54.

- R. Bosworth Smith, in his Carthage and the Carthaginians (London: Longmans, Green 1878, 1908) at 38, laments that Sallust declined to directly address the history of the city of Carthage.

- Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene. Royal scholarship on Rome's African frontier (New York: Routledge 2003), at 183, 191, in his Chapter 8: "Libyka" (183–211) [cf., 179]; also at 19, 27, 159 (Juba's library described), 177 (per his book on Hanno).

- Juba II's literary works are reviewed by D. W. Roller in The World of Jube II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at chapters 7, 8, and 10.

- Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker (Leiden 1923–), ed. Felix Jacoby, re "Juba II" at no. 275 (per Roller (2003) at xiii, 313).

- Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (2003) at 189, n22; cf., 177.

- Pliny the Elder (23–79), Naturalis Historia V, 8; II, 169.

- Cf., Picard and Picard, The Life and Death of Carthage (Paris: Hachette [1968]; New York: Taplinger 1969) at 93–98, 115–119.

- Serge Lancel, Carthage. A History (Paris 1992; Oxford 1995) at 358–360.

- See section herein on Berber relations. See Early History of Tunisia for both indigenous and foreign reports concerning the Berbers, both in pre-Punic and Punic times.

- Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (London: British Museum, Berkeley: University of California 2000) at 21–22 (affinity), 95–96 (economy), 115–119 (religion), 137 (funerals), 143 (art).

- David Diringer, Writing (London: Thames and Hudson 1962) at 115–116. The Ugarit tablet were discovered in 1929.

- Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids: 1987) at 1027–1028.

- Markoe, Phoenicians (2000) at 119. Eusebius of Caesarea (263–339), the Church Historian, quotes the Greek of Philo of Byblos whose source was the Phoenician writings of Sanchuniathon. Some doubt the existence of Sanchuniathon.

- Cf., Attridge & Oden, Philo of Byblos (1981); Baumgarten, Phoenician History of Philo of Byblos (1981). Cited by Markoe (2000).

- Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Praeger 1962, 2d ed. 1963) at 83–84.

- Sabatino Moscati, Il Mondo dei Fenici (1966), translated as The World of the Phoenicians (London: Cardinal 1973) at 55. Prof. Moscati offers the tablets found at ancient Ugarit as independent substantiation for what we know about Sanchuniathon's writings.

- Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 128–129.

- The ancient Romanized Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37–100s) also mentions a lost Phoenician work; he quotes from a Phoenician History of one "Dius". Josephus, Against Apion (c.100) at I:17; found in The Works of Josephus translated by Whiston (London 1736; reprinted by Hendrickson, Peabody, Massachusetts 1987) at 773–814, 780.

- Glenn E. Markoe, Phoenicians (Univ.of California 2002) at 11, 110. Of course, this also applies to Carthage. Cf., Markoe (2000) at 114.

- Strabo (c. 63 B.C. – A.D. 20s), Geographica at III, 5.11.