Carthage National Museum

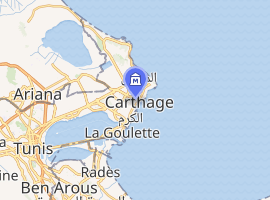

Carthage National Museum is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthage. Founded in 1875, it houses many archaeological items from the Punic era and other periods.

| |

| |

| Established | 1875 |

|---|---|

| Location | Carthage, Tunisia |

| Coordinates | 36.8533°N 10.324°E |

| Type | National museum |

| Website | The Carthage Museum |

The Carthage National Museum is located near the Cathedral of Saint-Louis of Carthage. It allows visitors to appreciate the magnitude of the city during the Punic and Roman eras. Some of the best pieces found in excavations are limestone/marble carvings, depicting animals, plants and even human sculptures. Of special note is a marble sarcophagus of a priest and priestess from the 3rd century BC, discovered in the necropolis of Carthage. The Museum also has a noted collection of masks and jewelry in cast glass, Roman mosaics including the famous "Lady of Carthage", a vast collection of Roman amphoras. It also contains numerous local items from the period of the Byzantine Empire. Also on display are objects of ivory.

History of the museum

The museum was founded in 1875 by Cardinal Charles Martial Lavigerie in the premises of the monastery; its name until 1956 was the Museum Lavigerie.

The museum is the product of excavations conducted by European archaeologists, in particular those made by Alfred Louis Delattre. The Annex was used at first to house the items found in searches in the necropolis of Carthage and excavations of the St. Louis hill but also Douimès, the hill of Juno, the Sainte-Monique Hill and also the Carthaginian Christian basilicas. However, many object unearthed were sold to tourists when the museum had a number of examples of similar objects.[1]

The museum received its present name in 1956 and opened for the first time as a national museum in 1963. It has undergone extensive restructuring in the 1990s, and has now been redesigned to accommodate new discoveries on the site of Carthage, especially the product of searches conducted as part of the international campaign of the UNESCO, from 1972-1995.

Punic collections

Phoenician

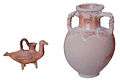

The various excavations at the site have uncovered numerous items characterizing the Phoenician civilization. The museum contains items which reveal a distinct connection with the Levant steeped in Egyptian and in particular Greek culture, and the ties of Carthage with Sicily during the Hellenistic period. Testimonies to these connections are many objects of pottery, oil lamps and amulet s discovered in excavating the necropolis.

The museum has a fine collection of Punic ceramics found from the late 19th century. A number of lamps were found during the excavation of pottery kilns dating back to the Third Punic War.[2]

The amulets of Egyptian deities (Isis, Osiris, Horus, and Bès) indicates the importance of ties between the Phoenicians and the Ancient Egypt, the first retaining these cultural elements once they arrived in the Western Mediterranean.

Funeral objects

Beautiful sarcophagi, which are dated to the end of the Punic era, have been found in the necropolis. Among these is the sarcophagus of the priest and the priestess, which is on display in the museum. The priest has the right hand raised in a gesture of blessing[3] The left hands of the two figures carry vases containing incense for liturgical purposes.[4]

Masks of glass also represent numerous deities, including objects which were intended to protect the deceased against the evil eye. There are also various items including razors made of bronze and richly decorated with cast patterns, illustrating Egyptian and Greek influences.[5] A number of Punic amulets are also on display.

Punic religion

The terracotta perfume-burner in the form of the head of Ba'al Hammon was discovered in a sanctuary in the Salammbô quarter unearthed by Dr Louis Carton shortly after World War I.; at the same time diverse other cultural objects came to light, including representations of Demeter[6]

The steles of the topheth are on the other the most important collection that is available. Although stelae were reported in the early research on the site of Carthage, especially during searches of Pricot of Mary (1874), most of which ran with the Magenta 'in 1875, many of the most interesting parts are deposited in the museum after the discovery of the sanctuary in 1921 in addition to the most common steles sandstone's El Haouaria, steles later limestone subject most often varied scenery: ships, palm trees, elephants and even elements portraits strong Hellenistic influence. Sometimes this is an inscription on the stele. Masks shaped in the form of the head of Ba'al Hammon are exposed, particularly a large mask discovered by Dr. Louis Carton in the early 20th century.

The content of the "chapel Cintas' discovery topheth by Pierre Cintas in 1947, is the subject of its own window. Two foundation deposits containing mostly ceramics were discovered, one located at the base of a wall and the other called "hideout" was under the floor of a small vaulted room.[7]

Punic architecture

There are some architectural elements of the Punic city on display, especially fragments of columns and pillars and structures.

Also outlined is a Phoenician inscription on black marble called "registration édilitaire", found in 1954.[8]

Limestone elephant stele

Limestone elephant stele Stele with palms

Stele with palms Mask and Punic steles

Mask and Punic steles Part of the furniture in the Cintas chapel, at the topheth

Part of the furniture in the Cintas chapel, at the topheth Grand marble sarcophagus

Grand marble sarcophagus Punic oil lamps

Punic oil lamps Punic oil lamps and ceramics

Punic oil lamps and ceramics Jewelry

Jewelry

Roman collections

Evidence of the 146 battle: The remains of the siege

The history of the Roman city of Carthage begins with a disaster, the will to destroy a rival dating from 146, which has some moving testimonies from the period on showcase. Common items on display are bullets, swords and stone catapults. A skeleton of one of fighters who died violently, is also exposed.

Roman art

Elements of the official Roman art were discovered on the Byrsa hill, including sculptures and bas reliefs depicting victory. These excavated items have been interpreted as a commemoration of the victory over the Parthians in 166, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and presented on a triumphal arch or monument portal.[9][10]

In addition, works from the reign of Augustus are presented including numerous busts. A remarkable representation of Auriga, holding a whip and a jug, a symbol of victory, is also exposed. This recent discovery is a valuable testimony to the attention of the Roman circus in the city, which was the second in size after the Circus Maximus in Rome.[11]

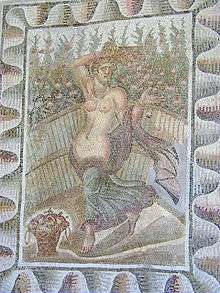

Mosaics

Although the collections of mosaics of the museum are not comparable to those of Bardo National Museum, the fact remains that genuine masterpieces are found in the museum. Among the recent discoveries, are from the panels found in a private spa located in Sidi Ghrib, near Tunis. It represents a topless woman running through a rose garden surrounded by water.[12] On the same site a panel of marble and limestone was discovered showing the activity of a matron at the end of the bath. It shows the individual seated on the toilet, surrounded by two servants, one of which holds a mirror and the other carrying a basket with various jewels. At the ends of the mosaic, the artist presents the bath accessories: a pair of sandals, a basket of laundry, a jug, etc.[13]

- Roman funerary statues

Roman amphora

Roman amphora Grand relief of the victory

Grand relief of the victory Roman Imperial statue

Roman Imperial statue Sidi Ghrib: Rosegarden mosaic

Sidi Ghrib: Rosegarden mosaic Sidi Ghrib:Matron on the toilet mosaic

Sidi Ghrib:Matron on the toilet mosaic

Christian and Byzantine Collections

Testimonies of Ancient Christianity

The mosaic of the four evangelists discovered in Carthage represents each of the four evangelists. In the center is a sphere in which integrates a cross. This work symbolizes the triumph of Christianity and its distribution to the four cardinal points by Liliane Ennabli.[14]

Features of African Christianity at the time, such as ceramic tiles decorated with religious motifs were also excavated and are on display. Many of them are relatively large with decorative details which were intended to depict of the themes of the Old Testament including Daniel and the Lion's Den.

A large number of funerary inscriptions discovered by Alfred Louis Delattre are displayed in the Carthage museum, found during his excavation of the main basilica.

Byzantine Civilisation

.jpg)

The famous "Lady of Carthage" mosaic dated back probably to the 6th century, is traditionally regarded as a portrait of a Byzantine empress.[15] The technique of alternating mosaic tiles and glass tiles, the fineness of the design and elegance of the subject makea it a major piece of art mosaic from the Late Antiquity.

See also

References

- Azedine Beschaouch,The Legend of Carthage, ed. Gallimard, Paris, 1993: 44

- Edward Lipinski [eds.],Dictionary of the Phoenician and Punic civilization, ed. Brepols, Paris, 1992 254

- André Parrot, Maurice H. Chéhab and Sabatino Moscati, Les Phéniciens, éd. Gallimard, coll. L’univers des formes, Paris, 2007, p. 214

- Hédi Slim et Nicolas Fauqué, La Tunisie antique. De Hannibal à saint Augustin, éd. Mengès, Paris, 2001, p. 73

- Hédi Dridi, Carthage et le monde punique, éd. Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 2006, pp. 221-222

- Hédi Slim and Nicolas Fauqué, op. cit., p. 61

- Fethi Chelbi, « La chapelle Cintas », La Méditerranée des Phéniciens. De Tyr à Carthage, éd. Somogy, Paris, 2007, p. 242

- M’hamed Hassine Fantar, « Architecture punique en Tunisie », La Tunisie, carrefour du monde antique, éd. Faton, Paris, 1995, p. 6

- Colette Picard, Carthage, éd. Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1951, p. 36

- Gilbert Charles-Picard, L’art romain, éd. Presses universitaires de France, Paris, 1962, p. 50

- Azedine Beschaouch, op. cit., pp. 107-108

- Hédi Slim et Nicolas Fauqué, op. cit., p. 230

- Mohamed Yacoub, Splendeurs des mosaïques de Tunisie, éd. Agence nationale du patrimoine, Tunis, 1995, p. 222

- Liliane Ennabli, Carthage, une métropole chrétienne, éd. CNRS, Paris, 1997

- Mohamed Yacoub, op. cit., p. 360

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carthage National Museum. |