Roman people

The Romans (Latin: Rōmānī, Classical Greek: Rhōmaîoi) were a cultural group, variously referred to as an ethnicity[3] or a nationality,[4] that in classical antiquity, from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD, came to rule large parts of Europe, the Near East and North Africa through conquests made during the Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire. The Romans themselves did not see being "Roman" as something based on shared language or inherited ethnicity, but saw it as something based on being part of the same larger religious or political community and sharing common customs, values, morals and ways of life.

Latin: Rōmānī Ancient Greek: Rhōmaîoi | |

|---|---|

Six of the Fayum mummy portraits, contemporary portraits of people in Roman Egypt from the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD. | |

| Total population | |

| 400.000 (114 BC)[n 1] 4 million (28 BC)[n 2] 6 million (47 AD)[n 3] 39.3 million (350 AD)[n 4] | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Imperial cult, Roman religion, Hellenistic religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Mediterranean Sea peoples, other Italic peoples, modern Romance peoples and Greeks |

The city of Rome is traditionally held to have been founded in 753 BC,[5] its early inhabitants constituting just one group of the many Italic peoples in the Italian peninsula. As the land under Roman dominion continued to increase, citizenship was gradually granted to the various peoples under Roman rule. The number of Romans rapidly increased due to the creation of colonies throughout the empire, through grants of citizenship to veterans of the Roman army, and through personal grants by the Roman emperors. In 212 AD, Emperor Caracalla extended citizenship rights to all the inhabitants of the Roman Empire through his Antonine Constitution.

Roman identity in Western Europe survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century as a diminished but still important political resource. It was only with the wars of the eastern Emperor Justinian I, aimed at restoring the western provinces to imperial control, that "Roman" began to fade as an identity in Western Europe, more or less disappearing in the 8th and 9th centuries and increasingly being applied by westerners only to the citizens of the city of Rome. The city itself continued to be important to Western Europeans but this importance stemmed from Rome being the seat of the Pope, not from it once having been the capital of a great empire. However, in the primarily Greek-speaking eastern empire, often called the Byzantine Empire by modern historians, Roman identity survived until its fall in 1453 and beyond, despite some interruption of the Empire's existence during the Frankokratia and ensuing rise of the Hellenic-Orthodox national consciousness against the Crusaders of Latin West, with the Roman identity in the east undergoing transition from an universal/multiethnical one to a precursor of a Greek nationalistic one.

Roman identity even survives today, though in a significantly reduced form. "Roman" is still used to refer to a citizen of the city itself and the term Romioi is sometimes (albeit rarely) used as their identity by modern Greeks. Additionally, the names and identities of some Romance peoples remain connected to their Roman roots especially in the Alps (such as the Romansh people and the Romands) and the Balkans (such as the Romanians, Aromanians and Istro-Romanians).

Meaning of "Roman"

The term "Roman" is typically used interchangeably to describe a historical timespan, a material culture, a geographical location and a personal identity. Though these concepts are obviously related, they are not identical. Although modern historians tend to have a preferred idea of what being Roman meant, so-called Romanitas (a term rarely used in Ancient Rome itself), the idea of "Romanness" was never static or unchanging.[6] What being Roman meant and what Rome itself was would have been viewed considerably different by a Roman under the Roman Republic in the 2nd century BC and a Roman living in Constantinople in the 6th century AD. Even then, some elements remained common throughout much of Roman history.[6]

Crucial to understanding Roman identity is that unlike other ancient peoples, such as the Greeks or Gauls, the Romans did not see their common identity as one necessarily based on shared language or inherited ethnicity. Instead, the important factors of being Roman were being part of the same larger religious or political community and sharing common customs, values, morals and ways of life.[7]

Roman Republic

Political history

One of the most important aspects of ancient Roman life was warfare; the Romans went on military campaigns almost every year, rituals marked the beginning and the end of the campaigning seasons and elections of chief magistrates (commanders of the army) generally took place on the Campus Martius ("Field of Mars", Mars being the Roman god of war). All Roman citizens were liable for military service, with most serving for several years during their youth. All soldiers could earn honors and rewards for valor in battle, though the highest military reward of all, the triumph, was reserved for commanders and generals.[8] Roman warfare was not overwhelmingly successful for the first few centuries of the city's history, with most campaigns being small engagements with the other Latin city-states in the immediate vicinity, but from the middle of the 4th century BC onwards, the Romans won a series of victories which saw them rise to rule all of Italy south of the Po river by 270 BC. Following the conquest of Italy, the Romans waged war against the great powers of their time; Carthage to the south and west and the various Hellenistic kingdoms to the east, and by the middle of the second century BC, all rivals had been defeated and Rome became recognized by other countries as the definite masters of the Mediterranean.[9]

Although Roman technological prowess and their ability to adopt strategies and technology from their enemies made their army among the most formidable in the ancient world, the Roman war machine was also made powerful by the vast pool of manpower available for the Roman legions. This manpower derived from the way in which the Romans had organized their conquered land in Italy. By the late 3rd century BC, about a third of the people in Italy south of the Po river had been made Roman citizens (meaning they were liable for military service) and the rest had been made allies, frequently called on to join Roman wars.[9] These allies were eventually made Roman citizens as well after refusal by the Roman government to make them so was met with the Social War (91–88 BC), after which Roman citizenship was extended to all the people south of the Po river.[10] In 49 BC, citizenship rights were also extended to the people of Cisalpine Gaul by Julius Caesar.[11]

Though Rome had throughout its history been continually generous with its granting of citizenship than other city states, granting significant rights to peoples of conquered territories, immigrants and their freed slaves, it was only with the Social War that a majority of the people in Italy became recognized as Romans, with the number of Romans rapidly increasing throughout the centuries that followed due to further extensions of citizenship.[11]

Roman citizenship

Though it could be explicitly granted by the Roman people to non-citizens, Roman citizenship (or civitas) was automatically granted to children whose parents consisted of either two Roman citizens or one citizen and one peregrinus ("foreigner") who possessed connubium (the right to a Roman marriage). Citizenship allowed for participation in Roman affairs, such as voting rights. By the time of the 3rd century BC, Romans of all social classes held nominally equal voting rights, though the value of your vote was tied to your personal wealth. In addition to voting rights, citizenship also made citizens eligible for military service and public office, both of these rights also tied to wealth and property qualifications.[12]

The Latin Rights, which originally encompassed Latium but was then extended to encompass most of Italy, ensured that most of the people in Italy enjoyed the benefits of Roman citizenship but lacked voting rights. Because they were bound to Rome and often called upon for military service but lacked the rights of the Roman citizens, Rome's Italian allies rebelled in the Social War, after which the Latin Rights in their traditional sense were more or less abolished in favor of a complete integration of the people in Italy as Romans.[12]

Typically, a non-citizen could acquire Roman citizenship through five different mechanisms:

- Non-citizens who served in the Roman army were typically granted citizenship.[13]

- Men without citizenship could obtain it through holding office in cities and other settlements with the Latin right.[13]

- Specific individuals could be granted citizenship directly.[13]

- Whole communities could receive "block grants", with all their inhabitants becoming citizens.[13]

- Slaves freed by Roman citizens became Roman citizens themselves.[13]

(Ancient/Classical) Roman Empire

Extensions of citizenship

The populace in the early Roman Empire was composed of several groups of distinct legal standing, including the Roman citizens themselves (cives romani), the provincials (provinciales), foreigners (peregrini) and free non-citizens such as freedmen (freed slaves) and slaves. Roman citizens were subject to the Roman legal system while provincials were subject to whatever laws and legal systems had been in place in their area at the time it was annexed by the Romans. Over time, Roman citizenship was gradually extended more and more and there was a regular "siphoning" of people from less privileged legal groups to more privileged groups, increasing the total percentage of subjects recognized as Roman citizens (e.g. Romans) though the incorporation of the provinciales and peregrini.[14]

The Roman Empire's capability to integrate peoples in this way was one of the key elements which ensured its success. In Antiquity, it was significantly easier to become a Roman than it was to become a member or citizen of any other contemporary state. This aspect of the Roman state was seen as important even by some of the emperors. For instance, Emperor Claudius pointed it out when questioned by the senate on admitting Gauls to join the senate:

What else proved fatal to Lacedaemon or Athens, in spite of their power in arms, but their policy of holding the conquered aloof as alien-born? But the sagacity of our own founder Romulus was such that several times he fought and naturalized a people in the course of the same day![15]

From the Principate onwards, "barbarians" (peoples from beyond Rome's borders) settled and integrated into the Roman world. Such settlers would have been granted certain legal rights simply by being within Roman territory, becoming provinciales and thus being eligible to serve as auxilia (auxiliary soldiers), which in turn made them eligible to become full cives Romani. Through this relatively rapid process, thousands of former barbarians could quickly become Romans. This tradition of straightforward integration eventually culminated in the Antonine Constitution, issued by Emperor Caracalla in 212, in which "all the people of the Roman world" (e.g. provinciales, peregrini and freedmen alike) were formally granted Roman citizenship.[16] At this point, Roman citizenship in the empire was not as significant as it had been in the republic, chiefly due to the change from a republican to an imperial government invalidating the need for voting rights and because service in the Roman military was no longer compulsory.[12] Caracalla's grant contributed to a vast increase in the number of people with the nomen (name indicating familial association) Aurelius (Caracalla was a nickname for the emperor, whose actual name was Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus).[17]

By the time of Caracalla's edict, there were already many people throughout the provinces who were considered (and considered themselves) Romans; through the centuries of Roman expansion large numbers of veterans and opportunists had settled in the provinces. Colonies founded by Julius Caesar and Augustus alone saw between 500.000 and a million people from Italy settled in Rome's provinces. Around the time of Augustus's death, four to seven percent of the free people in the provinces of the empire were Roman citizens.[11] In addition to colonists, many provincials had also become citizens through grants by emperors (who sometimes granted citizenship to individuals, families or cities), holding offices in certain cities or serving in the army.[18]

Romans in Late Antiquity

By Late Antiquity, many inhabitants of the Roman Empire had become Romani, with the term no longer simply being a civic designation for a citizen of the city of Rome, but referred to a citizen of the orbis Romanus, the Roman world. By this time, the city of Rome had lost its exceptional status in the empire. The historian Ammianus Marcellinus, definitely one of the Romani, hailing from modern-day Greece, wrote in the 4th century and refers to Rome almost as a foreign city, full of vice and corruption. Few of the Romani probably embodied all aspects of what the term had previously meant, many of them would have come from remote or less prestigious provinces and practiced religions and cults unheard of in Rome itself. Many of them would also have spoken "Barbarian" languages or Greek instead of Latin.[15]

The prelevant view of the Romans themselves was that the populus Romanus, Roman people, represented a "people by constitution" as opposed to Barbarian peoples such as the Franks or Goths, who were described as gentes ("people by descent"; ethnicities). To the people of the empire, "Roman" was just one layer of identification, in addition to local identities (similar to local and national identities today, a person from California can identify him/herself as a "Californian" within the context of the United States and an "American" in the context of the world).[15] If a person originated from one of the major imperial regions, such as Gaul or Britannia, one might have been viewed as a Roman, but still distinct from Romans of other major regions. It is clear from the writings of later historians, such as the Gallo-Roman Gregory of Tours, that such lower levels of identity, such as being the citizen of a particular region, province or city, were important within the empire. This importance, combined with there being clearly understood differences between local populations (the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus comments on the difference between "Gauls" and "Italians" for instance) illustrates that there were no fundamental differences between the local Roman identities and the gentes-identities applied to Barbarians, though the Romans themselves would not have seen the two as equivalent concepts. In the late Roman army, there were regiments named after Roman sub-identities (such as "Celts" and "Batavians") as well as regiments named after gentes, such as the Franks or Saxons.[19]

Religion had been an important aspect of Romanitas since Pagan times and as Christianity gradually became the dominant religion in the empire, Pagan aristocrats became aware that power was slipping from their hands as times changed. Some of them began to emphasize that they were the only "true Romans" because they preserved the traditional Roman literary culture and religion. This view enjoyed some support by poets and orators, such as the orator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, who saw these Pagan aristocrats as preserving the ancient Roman way of life, which would eventually allow Rome to triumph over all of its enemies, as it had before. This movement was met with strong opposition from the leaders of the church in Rome, with some church leaders, such as Ambrose, the Archbishop of Mediolanum, launching formal and vicious assaults on paganism and those members of the elite which defended it. Followers of paganism viewed Rome as the greatest city in the empire because of its glorious Pagan past, and though Christians accepted Rome as a great city, it was great because of its glorious Christian present, not its Pagan past. This gave Romanitas a new Christian element, which would become important in later centuries. Though the city would be important as the source of auctoritas and the self-perception of the imperial elite, it was not as important politically during the late empire as it had been before.[20]

Later history in Western Europe

Romans in the post-Roman west

The end of direct imperial control in Western Europe did not mean an end to the Roman identity, which remained somewhat prominent for centuries.[15] The predominant socio-political situation in Western Europe between the death of the last Western emperor, Julius Nepos, in 480 and the wars of Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century was a more or less completely Barbarian military but also a more or less completely Roman civil aristocracy and administration, a situation different, but clearly evolved, from the situation that existed in Late Antiquity. The Romans in Western Europe at the time appear to have been somewhat confused; they were well aware that the Western Roman Empire was no longer functioning but seem to have been unaware that it had ended.[19]

The Barbarian kings in Western Europe often assumed imperial powers and took over imperial institutions, this practice was especially prominent in Italy since it was the empire's ancient heartland.[21] The early Barbarian kings of Italy, first Odoacer and later Theoderic the Great, acted ostensibly as viceroys to the remaining Roman emperor in Constantinople. Like the Western Roman emperors had done before them, these Barbarian kings continued to appoint western consuls which would in turn be accepted by the emperors in the east and by other Barbarian kings throughout Western Europe.[22] Although the Romans detested kings, a holdover from the anti-monarchical sentiment that had led to the foundation of the Roman Republic almost a thousand years prior, the title of rex, assumed by the Barbarian kings, formed a useful basis of authority that Barbarian rulers could use in diplomacy with other kingdoms and with the surviving imperial court in Constantinople.[19]

Theoderic was careful to maintain the loyalty of his Roman subjects (which represented the majority of the people in his kingdom) and he deliberately likened himself to the old emperors, minting coins in much the same way, wearing purple clothing in public and during official ceremonies and maintained his court at Ravenna in imperial splendor. Theoderic's laws, the Edictum Theoderici, were also clearly connected to Roman law in both content and form.[20] Emperor Anastasius I returned the Western Roman imperial regalia, held in Constantinople since they had been sent there by Odoacer in 476, to Italy, then ruled by Theoderic.[21] These imperial regalia appear to have been worn by Theoderic and there are references by Roman senators to Theoderic as an emperor, indicating that the citizens of Rome itself viewed these Barbarian kings as taking on the traditional role of the emperor. An inscription by Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius (western consul in 486, Praetorian prefect of Italy 486–493) titles Theoderic as dominus noster gloriosissimus adque inclytus rex Theodericus victor ac triumfator semper Augustus, but Theoderic himself appears to have preferred to title himself simply as "king".[23] Theoderic's unwillingness to assume the imperial title may have been mainly due to being careful not to insult the emperors in Constantinople.[20]

Roman law continued to be in use and be important in Western Europe through the early Middle Ages. Both the Visigoths and the Franks issued law collections which either explicitly mention, or presuppose, the existence of a large population of Romans within their territories as Barbarian laws distinguish between the Barbarians who live by their own laws and the Romans, who live by Roman law.[15]

It was still possible to become a "Roman citizen" in the west in the 7th century, as indicated by Visigothic and Frankish works referencing the benefits of doing so. There is preserved letters from both East and West around this time which reference the act of freeing slaves and making them Roman citizens; Pope Gregory the Great is recorded as having freed slaves and made them cives Romanos and there is documentation in Bari, part of Byzantine Italy, on a slave who was freed and thus became a politēs Rōmaiōn. Roman status could also be conferred on people who weren't slaves, a 731 law by the Lombard king Liutprand specifies that if a "Roman" married a Lombard wife, that wife and all children of the couple would become Roman and the wife's relatives would no longer have the right to sue her, perhaps an idea which seemed attractive to Lombard women who wanted to escape the control of their relatives.[15]

Possibility of reunification and Justinian's wars

Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire was not destined to develop into what later historians have referred to as the Dark Ages. One of many possibilities for Europe's future at the time was reunification through military action. In 510, most of Western Europe was under the control of two Barbarian kings; Clovis I of the Franks and Theoderic of the Goths. Both of these kings were called by the title Augustus by their Roman subjects, though neither formally adopted the title, and they were poised to war against each other. To their contemporaries, the looming conflict between the Goths and Franks might have looked like the next, perhaps decisive war in the struggle between the Gallic and Italian factions which had dominated inter-imperial relations in the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century (such as the war between Emperor Honorius and the usurper Constantine III). Had the war happened, and been as decisive as other battles in this period typically were, it is likely that the victorious king would have re-established the Western Roman Empire under his own rule.[19]

The war between Theoderic and Clovis never transpired, but the idea that a powerful Barbarian king might restore the Western Roman Empire under Barbarian rule saw the court at Constantinople beginning to emphasize its exclusive Roman legitimacy. Through the remaining part of its thousand-year history, the eastern empire would repeatedly attempt to assert its right to govern the West through military campaigns. A key development was what later historians have termed the "Justiniaic ideological offensive"; a re-writing of 5th century history which portrayed the West as lost to barbarian invasions (rather than the true situation, that the Barbarian rulers had been gradually given power by the Western emperors themselves and worked within a fundamentally Roman framework). This ideology is prominently seen in Procopius's Wars and Marcellinus Comes's Chronicle.[19]

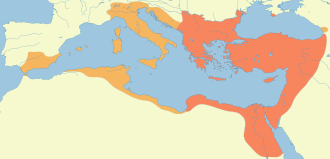

A fundamental turning point in what it meant to be Roman was the eastern emperor Justinian I's wars aimed at reconquering the lost provinces of the Western Roman Empire. By the end of his wars (533–555), the Justiniaic ideology that the west was no longer part of the Roman Empire had been asserted. Though Italy and North Africa were restored to imperial control, there could be no doubt in the aftermath of the wars that areas beyond Justinian's authority were no longer part of the Roman Empire and instead remained lost to Barbarians. This resulted in a dramatic decline in Roman identity beyond the regions controlled by the Byzantine Empire and led to the decisive end of the "Roman world" that had existed since the days of the Roman Republic.[19]

The Roman Senate continued to function during Gothic rule of Italy and senators dominated the politics within the city of Rome well into the Gothic Wars, during which the senate in the city eventually disappeared and most of its members moved to Constantinople instead. The Senate as an idea achieved a certain legacy in the west. In Gaul, members of the aristocracy were sometimes identified as "senators" from the 5th century to the 7th century and the Carolingian dynasty claimed to be descended from a former Roman senatorial family. In Spain, references to people of "senatorial stock" appear as late as the 7th century and in Lombard Italy, "Senator" became a personal name, with at least two people known to have had the name in the 8th century. The practice of representing themselves as "the Senate" was revived by the aristocracy within the city of Rome in the 8th century, though the institution itself was not revived.[15]

Disappearance of the Romans

There is substantial evidence that the meaning of "Roman" changed significantly during the 6th century. In the East, being Roman became defined not only by loyalty to the emperor but also increasingly by religious orthodoxy (though what that explicitly meant also changed through the ages). The Gothic Wars in Italy had split the Roman elite unto those who supported the Goths and later enjoyed Lombard rule and those who supported the emperor and later withdrew to regions still governed by the empire. With this, Roman identity no longer provided a sense of social cohesion. This, combined with the abolition of the senate in Rome itself, removed groups of people who had previously always set the standard for what "Roman" was supposed to mean. Through the centuries that followed, the division between the non-Roman and Roman parts of the population faded in the west as Roman political unity collapsed.[15]

This decline in people identifying as Romans in the west can be prominently seen in northern Gaul. In the 6th century, the personnel of churches in northern Gaul had been dominated by people with Roman names, for instance only a handful of names of non-Roman and non-Biblical origin are recorded in the episcopal list of Metz from before the year 600, a situation that is reversed after 600 when bishops had predominantly Frankish names. The reason for this change in naming practices might be a change in naming practices in Gaul, that people entering church services no longer adopted Roman names or that the Roman families which had provided the church personnel dropped in status.[19]

In Salic law, produced under Clovis I around the year 500, the Romans and the Franks are two parallel major populations in the Frankish kingdom and although the Franks have somewhat of an advantage, both have well-defined legal statuses. A century later in the Lex Ripuaria, the Romani are just one of many smaller semi-free populations, restricted in their legal capacity. This legal arrangement would have been unthinkable during the rule of the Roman Empire, and even under the reign of Clovis.[19]

Through the early Middle Ages, the legal significance of having Roman status also faded away in Western Europe and spoken Latin fragmented and split into what would develop into the modern Romance languages. The unifying and sometimes contradictory Roman identity was replaced with local identities based on the region one was from (such as Provence or Aquitania). Where Romans had once been accepted as making up the majority of the population, such as in Hispania and Gaul, they quietly faded away as their descendants accepted other names and identities.[15] The benefit of abandoning the identity as Roman and reverting to more local identities was that local identities were not binary opposed to the identity as a "Frank" or "Goth" and could exist together with them, providing legal advantages that "Roman" no longer did.[19] Furthermore, it is possible that people who identified as "Romans" were victims of anti-Roman sentiments, as experienced by the 7th century Saint Goar of Aquitaine. Although Roman identity would linger on in Western Europe in some places, mostly being restricted to a few minorities in the alpine regions, some residual meanings of "Roman" would remain important through the Middle Ages, such as "Roman" as a citizen of the Byzantine Empire or "Roman" as a citizen of the city of Rome or representative of the Roman Catholic Church.[15]

The significance of being a Roman thus eventually completely disappeared in Western Europe, together with the Roman identity itself. 8th century sources from Salzburg still reference that there was a social group in the city called the Romani tributales but Romans at this time mostly merged with the wider tributales (tributary peoples) distinction rather than having a separate Roman distinction in Frankish documents. Throughout most of former Gaul, the Roman elite which had lingered for centuries merged with the Frankish elite and lost their previously distinct identity and though "Romans" continued to be a dominant identity in regional politics in southern Gaul for a while, the specific references to some individuals as "Romans" or "descendants of Romans" indicates that the Roman status of some people in Gaul was perhaps no longer being taken for granted and needed pointing out. The last groups of Romani in the Frankish realm lingered for some time, especially in Salzburg and Raetia, but seem to fade away in the early 9th century[15] (except for the Romansh people in southeastern Raetia).[24]

By 800, when Charlemagne was crowned as a new Roman emperor in Rome, the first time an emperor was crowned in Rome itself since antiquity, self-identification as a Roman was largely gone in Western Europe. Nevertheless, the name of Rome was to remain a source of power and prestige throughout history, becoming associated with two most powerful figures of the Catholic Western Europe(the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor) and also being invoked by later aristocratic medieval families who sometimes proclaimed and were proud of their alleged Roman origins.[15]

Reversion to association with the city of Rome

As the seat of the Pope, the city of Rome continued to hold significance despite the fall of the Western Roman Empire and sack of the city by both the Visigoths and the Vandals.[15] Although the glorious past of Rome was remembered in medieval times, whatever power Rome had once held was completely overshadowed by the city being the seat of the Papal see. In the 6th century writings of Gregory of Tours, Rome is always described as a Christian city, first being mentioned once St. Peter arrives there. The longest discussion on Rome is about the election of Pope Gregory the Great and Gregory of Tours appears indifferent to Rome at one point having been the capital of a great empire.[20]

Through the early Middle Ages, the term Romani became more and more heavily associated by authors in Western Europe with the population of the city itself, or the population of the larger Duchy of Rome. The change from an identity applied to people throughout Italy to an identity applied to the city itself can be pinpointed to the 6th century; Cassiodorus, who served the Gothic kings, use the term Romani to describe Roman people across Italy and Pope Gregory the Great, at the end of the 6th century, uses Romani almost exclusively for the people in the city. The Historia Langobardorum, written by Paul the Deacon in the 8th century, postulates that the term civis Romanus ("Roman citizen") is applied solely to someone who either lived in, or was born in, the city of Rome and it could for instance be applied to the Archbishop of Ravenna, Marinianus, only because he had originally been born in Rome. This indicates that the term at some point ceased to generally refer to all the Latin-speaking subjects of the Lombard kings and became restricted to the city itself.[15]

After the Byzantine Empire restored imperial control over Rome, the city had become a peripheral city within the empire. Its importance stemmed from being the seat of the Pope, the first in order among five foremost Patriarchs of the Church, and the city's population was not specially administered and lacked political participation in wider imperial affairs except for its interactions with the papacy.[25] Under Byzantine rule, the Popes often used the fact that they had the backing of the "people of Rome" as a legitimizing factor when clashing with the emperors. The political implications of the name and citizenry of Rome thus remained somewhat important, at least in the eyes of the westerners.[15]

.jpg)

When the temporal power of the popes was established through the foundation of the Papal States (established through the Frankish king Pepin granting control of former Byzantine provinces conquered from the Lombards to the Pope), the population of the city of Rome became a constitutional identity which accompanied and supported the sovereignty of the popes. In the minds of the contemporary popes, the sovereign of the Papal States was St. Peter, who delegated control to his vicars on Earth, the popes. However, the popes were too deeply rooted in the Roman imperial system to imagine a worldly government established only on religious relationships. As such, the "Romans" became the political body of this new state and the term, once used for all the inhabitants of Byzantine Italy, became increasingly used to exclusively refer to the inhabitants of the city. After Pepin's donations the Popes also revived the concept of respublica Romanorum as something associated with, but distinct from, the Church. In the new version of the idea, the Pope was the lord of the Romans but the Romans themselves, as citizens of Rome, had a share in the public rights connected to the sovereignty of the city.[25]

Medieval sources on the "Romans" as the people living in Rome are generally quite hostile. The Romans are frequently described as being "as proud as they are helpless" and as speaking the ugliest of all the Italian dialects. Because they repeatedly attempted to take a position independent from the Papacy and/or the Holy Roman emperors (both of whom were considered as more universal rulers whose policies extended much further than the city itself), the Romans were often seen as intruders in affairs that exceeded their competence. The Romans people were in turn overwhelmingly negatively oriented towards the Franks, which they identified as "the Gauls". The Frankish emperors from Charlemagne onwards decreed that Frankish law could be used in the courts of their empire when demanded, which soured relations, and Frankish nobility which visited Italy and Rome would often speak in their own Frankish language when they did not want the Romans to understand them. Roman sources from this time typically describe "the Gauls" as vain, aggressive and insolent. The Roman dislike for the Franks sometimes turned into fear as the Franks would more and more frequently appear outside their gates with armies.[25]

Despite this fear, the population of Rome and people in most other parts of Italy (with the exception of southern Italy, still under Byzantine influence) saw Charlemagne and his successors as true Roman emperors.[26] The reasons for this were many. Although the Romans accepted that there was continuity between Rome and Constantinople, and saw the Carolingian emperors as having more to do with the Lombard kings of Italy than the ancient Roman emperors,[26] the Byzantines were often seen as Grieci ("Greeks") rather than Romans and were seen as having abandoned Rome, the seat of empire, and lost the Roman way of life and the Latin language; thus the empire ruling in Constantinople hadn't survived, but had fled from its responsibilities. This disconnect shows that the city of Rome and the Byzantines had grown very far apart from each other.[27] To the Romans and Italians of the 8th and 9th century, the original Roman Empire was a thing of the past. There definitely used to be an empire, such as during the time of Constantine the Great, but it had now transferred itself to the Eastern Mediterranean and ceased to be properly Roman, now inhabited by "Greeks". Rome was no longer a city of emperors, but was the city of St. Peter only. A real Roman Empire could have only one capital, Rome, and its possible existence rested on the man who ruled in Rome, the Pope. As such, the new emperors in the West (an office that eventually developed into the Holy Roman emperors) could be emperors only because they were crowned and anointed by the Pope.[26] The support of what was perceived by Western Europe as the populus Romanus was a highly important factor during Charlemagne's coronation. Charlemagne himself actively hoped to suppress the idea of Romani as an ethnicity in an effort to avoid that the imperial title could be bestowed by the population of Rome in the same way that the Franks could proclaim a rex Francorum (King of the Franks).[15]

Later history in the Eastern Mediterranean

Romans in the Byzantine Empire

In stark contrast to the catastrophic collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire (frequently called the Byzantine Empire by modern historians) survived the 5th century more or less intact and its predominantly Greek-speaking population continued to identify themselves as Romans (Rhomaioi), as they remained inhabitants of the Roman Empire. The name Romania ("land of the Romans"), a later popular designation by the people of the Byzantine Empire for their country, is attested as early as 582 when it was used by the inhabitants of the city of Sirmium for their country. Although rarely expressed as an idea before the 9th century, the earliest mention of the Byzantine Empire as being "Greek" is from the 6th century, written by Bishop Avitus of Vienne in the context of the Frankish king Clovis I's baptism; "Let Greece, to be sure, rejoice in having an orthodox ruler, but she is no longer the only one to deserve such a great gift".[15] To the early Byzantines (up until around the 11th century) the term "Greeks" or "Hellenes" was offensive as it downplayed their Roman nature and furthermore associated them with the ancient Pagan Greeks rather than the more recent Christian Romans.[28]

The idea of the res publica remained an important imperial concept for centuries. In the Frankish king Childebert II's letters to Emperor Maurice, the emperor is called the princeps Romanae reipublicae and through the 6th and 8th centuries, terms such as res publica and sancta res publica was still sometimes applied to the Byzantine Empire by authors in Western Europe. This practice only ceased as Byzantine control over Italy and Rome itself crumbled and "Roman" as a name and concept became more heavily associated by Western authors with the city itself. The use of the term Romani was somewhat similar, usually often used in reference to the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire by early Medieval western authors when not used for the population of the city itself. In Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, the term Romani refers to the Byzantine Empire and their remaining garrisons in Spain and the term is never applied to the population of the former western provinces.[15]

References to the Romans as a gens, like the Barbarian gentes, begin to appear around the time of Justinian's conquests. Priscian, a grammarian who was born in Roman North Africa and later lived in Constantinople during the late 5th century and early 6th century, refers in his work to the existence of a gens Romana. Letters written by the Frankish king Childebert II to Emperor Maurice in Constantinople in the 580s talk of the peace between the two "gentes of the Franks and the Romans". The 6th century historian Jordanes, himself identifying as a Roman, refers to the existence of a Roman gens in the title of his work on Roman history, De summa temporum vel de origine actibusque gentis Romanorum. The idea of Romans as a gens like any other didn't become generally accepted in the East until the 11th century.[15] For instance, Emperor Basil I (r. 867–886) still considered "Roman" to be an identity that was defined as an opposite to being of a Barbarian gens.[27] Before the 11th century, the "Romans" discussed in Byzantine texts usually refer to individuals loyal to the Byzantine emperor who followed Chalcedonian Christianity. As such, the Romans were all the Christian subjects of the emperor.[15]

In the 27th chapter of Emperor Constantine VII's 10th century political treatise De Administrando Imperio, the emperor expressed the idea that the Imperium had been transferred from Rome to Constantinople once Rome stopped being ruled by an emperor. The 12th century historian John Kinnamos expresses similar views, seeing the rights to the imperium as having disappeared from Rome and the west since power passed there from the last Western Roman emperors to Barbarian kings who had no claim to being Roman. As such, the ruler in Constantinople was the sole ruler in Europe who could claim to be a true Roman. As such, the transfer of power from Rome to Constantinople that had begun under Constantine the Great had been finished once the last few Western Roman emperors were dethroned or killed. This view was important in Byzantine ideology as it served as the basis for their idea of unbroken continuity between Rome and Constantinople.[29]

The population within the Byzantine Empire saw themselves as living within the Roman Empire but were aware that their empire was no longer as powerful as it once had been. The 7th century text Doctrina Jacobi, set in Carthage, states that the territory ruled by the Romans had once stretched from Spain in the west to Persia in the east and Africa in the south to Britain in the north, with all the people in it having been subordinated to the Romans by the will of God. Though the old borders were still visible through the presence of monuments erected by the ancient emperors, the author of the Doctrina Jacobi stated that one could now see that the present Roman realm (the Romania) had been humbled.[30]

The losses that the empire had experienced, in particular the loss of the Levant, Egypt, and Northwest Africa in the Muslim conquests in the 7th century, were typically blamed on the heresy of the emperors (e.g. iconoclasm) and the Christians who had once lived in these lost regions ceased to be recognized by the Byzantines as "Romans". This eventually led to "Roman" being applied more to the dominant Greek-speaking population of the remaining empire than to inhabitants of the empire in general. The late 7th century was the first time (in the writings of St. Anastasios the Persian) that Greek, rather than Latin, was referred to as the rhomaisti (Roman way of speaking).[30] In Leo the Deacon's 10th century histories, Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas is described as having settled communities of Armenians, Rhomaioi and other ethnicities on Crete, indicating that Romans by this time were just one of the groups within the empire (for instance alongside the Armenians).[31] By the late 11th century, the transformation of "Roman" to an identity by descent rather than political or religious affiliation was complete, with references to people as "Rhomaios by birth" beginning to appear in the writings of Byzantine historians. The label was now also applied to Greek-speakers outside of the empire's borders, such as the Greek-speaking Christians under Seljuk rule in Anatolia, who were referred to as Rhomaioi despite actively resisting attempts at re-integration by the Byzantine emperors.[32]

Late Byzantine identity

After the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople in 1204 and shattered the Byzantine view of unbroken continuity from Rome to Constantinople, new alternative sources were required for the legitimacy of the Byzantines as Romans. The Byzantine elite thus began to increasingly detach their self-identity from the Roman Empire as a unit and look to Greek cultural heritage and Orthodox Christianity as the markers of what Romans were, and connected the contemporary Romans to the ancient Greeks as the precursors who had once ruled the current homeland of the Romans. Ethnic Romanness became increasingly identified as someone who was ethno-culturally Hellenic, an idea which was taken a step further by Emperors John III and Theodore II (who ruled at Nicaea while the Crusaders and their descendants occupied Constantinople), who stated that the present Rhomaioi were Hellenes, descendants of the Ancient Greeks.[33]

This is not to say that the Byzantines stopped identifying as Romans. The Byzantine view changed from Constantine the Great bestowing the empire to Constantinople to Constantine the Great bestowing the empire to the Hellenes and as such a Roman and a Greek was the same thing. This in no way invalidated them as Romans; though the Nicaean emperors explicitly referred to their lands and subjects as Hellenic, they also identified themselves as the only true Roman emperors. "Greek" and "Roman" were not contrasting or distinct identities, but building blocks of the same identity as Rhomaioi. This double-identity lasted beyond the 1261 reconquest of the city under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos and remained the main view on the issue by the time of the last few Byzantine emperors. In the text Comparison of the Old and the New Rome by Manuel Chrysoloras, addressed to Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, Rome is presented as the mother of the daughter Constantinople, a city founded by the two most wise and powerful peoples in the world, the Romans and the Hellenes, who came together to create a city destined to rule the entire world.[34]

Romans in the Ottoman Empire

Rhomaioi survived the 1453 Fall of Constantinople, the end of the Byzantine Empire, as the primary self-designation for the Christian Greek-speaking inhabitants in the new Turkish Ottoman Empire. The popular historical memory of these Rhomaioi was not occupied with the glorious past of the Roman Empire of old or the Hellenism in the Byzantine Empire but by legends of the fall and loss of their Christian homeland and Constantinople, such as the myth that the last emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos (who had died fighting the Ottomans at Constantinople in 1453), would one day return from the dead to reconquer the city.[35]

In the early modern period, an educated, urban-dwelling Turkish-speaker who was not a member of the military-administrative class would often refer to himself neither as an Osmanlı ("Ottoman") nor as a Türk ("Turk"), but rather as a Rūmī (رومى), or "Roman", meaning an inhabitant of the territory of the former Byzantine Empire in the Balkans and Anatolia. The term Rūmī was also used to refer to Turkish-speakers by the other Muslim peoples of the empire and beyond.[36] As applied to Ottoman Turkish-speakers, this term began to fall out of use at the end of the seventeenth century, and instead the word increasingly became associated with the Greek population of the empire, a meaning that it still bears in Turkey today.[37]

As a modern identity

Greeks

For centuries following the Fall of Constantinople, the dominant self-identity of the Greeks remained "Roman" (Romioi or Rhomaioi). The 18th century Greek scholar and revolutionary Rigas Feraios called for the "Bulgars and Arvanites, Armenians and Romans" to rise in arms against the Ottomans.[38] The 19th century general Yannis Makriyannis, who served in the Greek War of Independence, recalled in his memoirs that a friend had asked him "What say you, is the Roman State far away from coming? Are we to sleep with the Turks and awaken with the Romans?".[39]

For the Greeks, the Roman identity only lost ground by the time of the Greek War of Independence in the 19th century, when multiple factors saw the name "Hellene" rise to replace it. Among these factors were that names such as "Hellene", "Hellas" or "Greece" were already in use for the country and its people by the other nations in Europe, the absence of the old Byzantine government to reinforce Roman identity, and the term Romioi becoming associated with those Greeks still under Ottoman rule rather than those actively fighting for independence. In the eyes of the independence movement, a Hellene was a brave and rebellious freedom fighter while a Roman was an idle slave under the Ottomans.[40][41] Though some parts of Byzantine identity were preserved (notably a desire to take Constantinople itself), the name Hellene fostered a fixation on more ancient (pre-Christian) Greek history and a negligence for other periods of the country's history (such as the Byzantine period).[42]

Many Greeks, particularly those outside the then newly founded Greek state, continued to refer to themselves as Romioi well into the 20th century. Peter Charanis, who was born on the island of Lemnos in 1908 and later became a professor of Byzantine history at Rutgers University, recounts that when the island was taken from the Ottomans by Greece in 1912, Greek soldiers were sent to each village and stationed themselves in the public squares. Some of the island children ran to see what Greek soldiers looked like. ‘‘What are you looking at?’’ one of the soldiers asked. ‘‘At Hellenes,’’ the children replied. ‘‘Are you not Hellenes yourselves?’’ the soldier retorted. ‘‘No, we are Romans’’ the children replied.[43] The modern Greek people still sometimes use Romioi to refer to themselves, as well as the term "Romaic" ("Roman") to refer to their Modern Greek language.[44]

Western Romance peoples

In addition to the Greeks, another group of people who have continually self-identified as Roman since Antiquity are the present day citizens of the city of Rome, though modern Romans identify nationally and ethnically as Italians, with "Roman" being a local identity within the larger scope of Italy. Today, Rome is the most populous city in Italy with the city proper having about 2.8 million citizens and the Rome metropolitan area is home to over four million people.[45] Governments inspired by the ancient Roman Republic have been revived in the city four times since its ancient collapse; as the Commune of Rome in the 12th century (an opposition to Papal temporal power), as the government of Cola di Rienzo (who used the titles "tribune" and "senator") in the 14th century, as a sister republic to revolutionary France in 1798–1799 (which briefly restored the office of Roman consul) and in 1849 with a government based on the ancient Roman triumvirates.[46][47][48]

Though most of the Romance peoples that descended from the Romans following the collapse of Roman political unity in the 5th century diverged into groups no longer identifying as Romans, the name of Rome has remained associated with some modern Romance peoples. Examples of this are the Romansh people (descended from the Romani recorded in the Alps in the 8th and 9th centuries) and the Romands.[49] Romands represent the French-speaking community of Switzerland, with French being the native language of 20% of the Swiss people. Their homeland is called Romandy, which covers the western part of the country. Originally, the majority of the Romands spoke the Arpitan language (also known as Franco-Provençal), but it has been almost completely extinguished in favor of French.[50]

On the other hand, the Romansh people are an ethnic group living in southeastern Switzerland. This region, anciently known as Raetia, was inhabited by the Rhaetian people, with the Celtic Helvetii at their west. The ethnicity of the Rhaetians is uncertain, but their language was probably Indo-European with Celtic and perhaps Etruscan influences. The Rhaetians were conquered by the Romans in 15 AD. They were seen by the Romans as excellent fighters and were included in several legions, where their usage of Latin would start. Over the centuries, Latin would replace indigenous languages in Raetia, with Roman culture only strongly consolidated in the province during the times of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. After this, Germanic tribes would settle in the province, where they would eventually assimilate most of this Romanized Rhaetian population. The ones that resisted the Germanic invasions evolved into the modern Romansh people, who call their language and themselves as rumantsch or romontsch, derived from the Latin word romanice, which means "Romance".[24]

Balkan Romance peoples

The Balkan Romance peoples have also maintained their Roman identity over the centuries, and it has remained especially prominent in the Romanians. One of the main principles of Romanian identity and nationalism is the theory of Daco-Roman continuity. This theory claims that Dacia, after its conquest by Trajan, was so extensively colonized that the indigenous Dacians mixed with the Roman settlers, thus creating a culture of Daco-Romans. These would resist the invasions of Slavs and other peoples by hiding in the Carpathians, eventually evolving into the modern day Romanians. This theory is not universally accepted, however.[51] One of the earliest records of the Romanians being referred to as Romans is given in the Nibelungenlied, a German epic poem written before 1200 in which a "Duke Ramunc from the land of Vlachs (Wallachia)" is mentioned. "Vlach" was an exonym (name employed by forgeiners) used almost exclusively for the Romanians during the Middle Ages. It has been argued that "Ramunc" was not the name of the duke, but a collective name that highlighted his ethnicity. Other documents, especially Byzantine or Hungarian ones, also mention the old Romanians as Romans or their descendants.[52] Today, Romanians call themselves români and their nation România.[53]

The Aromanians are another Balkan Romance ethnic group scattered in the Balkans. Their origins are highly uncertain. Romanians often say that they originally were Romanians who migrated from north to south of the Danube and that they are still Romanians. The Greeks, on the other hand, say that they descend from indigenous Greeks and Roman soldiers placed there to guard the passes of the Pindus (and that they are therefore ethnic Greeks who speak a Romance language). The debates of their origins have been widely discussed throughout recent history, and the opinions of the Aromanians themselves are divided. Regardless of where they come from, the Aromanians have a large number of names with which they identify, among which are arumani, armani, aromani and rumani, all of them derived from "Roman".[54] Another group related to the last two are the Istro-Romanians, with some of them still calling themselves rumeri or similar names, although this name has lost strength and the Istro-Romanians often prefer to use different terms.[55] The Megleno-Romanians, the last of the Balkan Romance peoples, identified in the past as rumâni, but this name was completely lost centuries ago mostly in favor of vlasi, derived from "Vlach".[56]

See also

Notes

- The Roman census of 114 BC records there being 400.000 Roman citizens, with other people within Roman territory belonging to less privileged legal classes, such as provinciales (provincials) and peregrini (foreigners).[1]

- The Roman census of 28 BC records there being just 4 million Roman citizens in the empire (representing about a tenth of the empire's total c. 40 million inhabitants). The sharp increase in recorded Roman citizens between 114 BC and 28 BC may be explained by either an undocumented switch from recording just adult male citizens to recording women and children of citizen status or by the grant of citizenship to all of Italy and people in the provinces.[1]

- The Roman census of 47 AD records there being just over 6 million Roman citizens in the empire. This accounts for just 9 % of the total population of the empire (c. 70 million).[1]

- The increase in the number of Romans by the 4th century has its basis in the Antonine Constitution of 212 AD, which granted Roman citizenship to all inhabitants of the empire. In 350 AD, there were about 39.3 million people living in the empire.[2]

References

Citations

- Scheidel 2006, p. 9.

- Russell 1958.

- Gruen 2014, p. 426.

- Darling Buck 1916, p. 51.

- Enyclopaedia Britannica – Ancient Rome.

- Revell 2009, p. x.

- Woolf 2000, p. 120.

- Rich & Shipley 1995, p. 1.

- Rich & Shipley 1995, p. 2.

- Rich & Shipley 1995, p. 3.

- Lavan 2016, p. 2.

- Britannica.

- Lavan 2016, p. 7.

- Mathisen 2015, p. 153.

- Pohl 2018.

- Mathisen 2015, p. 154.

- Lavan 2016, p. 5.

- Lavan 2016, p. 3.

- Halsall 2018.

- Hen 2018.

- Jones 1962, p. 127.

- Jones 1962, p. 126.

- Jones 1962, p. 128.

- Billigmeier 1979.

- Delogu 2018.

- Granier 2018.

- West 2016.

- Cameron 2009, p. 7.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 72.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 74.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 79.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 80.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 85.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 86.

- Stouraitis 2017, p. 88.

- Kafadar 2007, p. 11.

- Greene 2015, p. 51.

- Rigas Feraios, Thurius, line 45.

- Makrygiannis 1849, p. 117.

- Ambrosius Phrantzes (Αμβρόσιος Φραντζής, 1778–1851). Επιτομή της Ιστορίας της Αναγεννηθείσης Ελλάδος (= "Abridged history of the Revived Greece"), vol. 1. Athens 1839, p. 398 ().

- Dionysius Pyrrhus, Cheiragogy, Venice 1810.

- Spyros Markezinis. Πολιτική Ιστορία της συγχρόνου Ελλάδος (= "Political History of Modern Greece"), book I. Athens 1920–2, p. 208 (in Greek).

- Kaldellis 2007, pp. 42–43.

- Merry 2004, p. 376; Institute for Neohellenic Research 2005, p. 8; Kakavas 2002, p. 29.

- World Population Review.

- Wilcox 2013.

- Vandiver Nicassio 2009, p. 21.

- Ridley 1976, p. 268.

- Minahan 2000, p. 776.

- Gess, Lyche & Meisenburg 2012, pp. 173–174.

- Light & Dumbraveanu Andone 1997.

- Drugaș 2016.

- Berciu Drăghicescu 2012.

- Ružica 2006.

- Burlacu 2010, pp. 15–22.

- Berciu Drăghicescu 2012, p. 311.

Cited bibliography

- Averil, Cameron (2009). The Byzantines. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- Berciu Drăghicescu, Adina (2012). "Aromâni, meglenoromâni, istroromâni: Aspecte identitare și culturale". Editura Universității Din București (in Romanian): 788.

- Billigmeier, Robert Henry (1979). A Crisis in Swiss pluralism: The Romansh and their relations with the German- and Italian-Swiss in the perspective of a millenium. Mouton Publishers. p. 450. ISBN 978-9-0279-7577-5.

- Burlacu, Mihai (2010). "Istro-Romanians: the legacy of a culture". Bulletin of the "Transilvania" University of Brașov. 3 (52): 15–22.

- Darling Buck, Carl (1916). "Language and the Sentiment of Nationality". American Political Science Review. 10 (1): 44–69. doi:10.2307/1946302. JSTOR 1946302.

- Delogu, Paolo (2018). "The post-imperial Romanness of the Romans". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Drugaș, Șerban George Paul (2016). "The Wallachians in the Nibelungenlied and their Connection with the Eastern Romance Population in the Early Middle Ages". Hiperboreea. 3 (1): 71–124. JSTOR 10.5325/hiperboreea.3.1.0071.

- Gess, Randall; Lyche, Chantal; Meisenburg, Trudel, eds. (2012). Phonological Variation in French: Illustrations from three continents. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 1–397. ISBN 9789027273185.

- Granier, Thomas (2018). "Rome and Romanness in Latin southern Italian sources, 8th - 10th centuries". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Greene, Molly (2015). The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, 1453 to 1768. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748693993.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2014). "Romans and Jews". In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.). A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444337341.

- Halsall, Guy (2018). "Transformations of Romanness: The northern Gallic case". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Hen, Yitzhak (2018). "Compelling and intense: the Christian transformation of Romanness". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Institute for Neohellenic Research (2005). The Historical Review. II. Athens: Institute for Neohellenic Research.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, A. H. M. (1962). "The Constitutional Position of Odoacer and Theoderic" (PDF). The Journal of Roman Studies. 52 (1–2): 126–130. doi:10.2307/297883. JSTOR 297883.

- Kafadar, Cemal (2007). "A Rome of One's Own: Cultural Geography and Identity in the Lands of Rum". Muqarnas. 24: 7–25. doi:10.1163/22118993_02401003.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2007). Hellenism in Byzantium: The Transformations of Greek Identity and the Reception of the Classical Tradition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87688-9.

- Kakavas, George (2002). Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance 15th–18th Century Treasures from the Byzantine & Christian Museum, Athens. Athens: Hellenic Ministry of Culture. ISBN 978-960-214-053-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lavan, Myles (2016). "The Spread of Roman Citizenship, 14–212 CE: Quantification in the Face of High Uncertainty" (PDF). Past & Present. 230 (1): 3–46. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtv043. hdl:10023/12646.

- Light, Duncan; Dumbraveanu Andone, Daniela (1997). "Heritage and national identity: Exploring the relationship in Romania". International Journal of Heritage Studies. 3 (1): 28–43. doi:10.1080/13527259708722185.

- Makrygiannis, Strategus (1849). Memoirs (book 1). Athens.

- Mathisen, Ralph W. (2015). "Barbarian Immigration and Integration in the Late Roman Empire: The Case of Barbarian Citizenship". In Sänger, Patrick (ed.). Minderheiten und Migration in der griechisch-römischen Welt. BRILL. ISBN 978-3-506-76635-9.

- Merry, Bruce (2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Greek Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313309841.

- Pohl, Walter (2018). "Introduction: Early medieval Romanness - a multiple identity". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Revell, Louise (2009). Roman Imperialism and Local Identities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88730-4.

- Rich, John; Shipley, Graham (1995). War and Society in the Roman World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415121675.

- Ridley, Jasper (1976). Garibaldi. Viking Press.

- Russell, J. C. (1958). "Late Ancient and Medieval Population". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 48 (3): 1–152. doi:10.2307/1005708. JSTOR 1005708.

- Ružica, Miroslav (2006). "The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians awakening, national policies, assimilation". Proceedings of the Globalization, Nationalism and Ethnic Conflicts in the Balkans and Its Regional Context: 28–30.

- Scheidel, Walter (2006). "Population and demography" (PDF). Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics.

- Stouraitis, Yannis (2017). "Reinventing Roman Ethnicity in High and Late Medieval Byzantium" (PDF). Medieval Worlds. 5: 70–94. doi:10.1553/medievalworlds_no5_2017s70.

- Vandiver Nicassio, Susan (2009). Imperial City: Rome under Napoleon. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226579733.

- Woolf, Greg (2000). Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521789820.

Cited web sources

- "Ancient Rome". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Civitas". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Rome Population 2020". World Population Review. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- West, Charles (2016). "Will the real Roman Emperor please stand up?". Turbulent Priests. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Wilcox, Charlie (2013). "Historical Oddities: The Roman Commune". The Time Stream. Retrieved 2016-12-18.