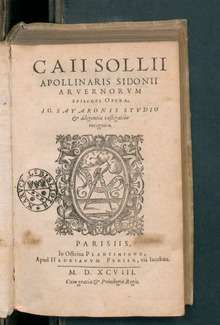

Sidonius Apollinaris

Gaius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius, better known as Saint Sidonius Apollinaris (5 November[1] of an unknown year, c. 430 – August 489 AD), was a poet, diplomat, and bishop. Sidonius is "the single most important surviving author from fifth-century Gaul" according to Eric Goldberg.[2] He was one of four Gallo-Roman aristocrats of the fifth- to sixth-century whose letters survive in quantity; the others are Ruricius, bishop of Limoges (died 507), Alcimus Ecdicius Avitus, bishop of Vienne (died 518) and Magnus Felix Ennodius of Arles, bishop of Ticinum (died 534). All of them were linked in the tightly bound aristocratic Gallo-Roman network that provided the bishops of Catholic Gaul.[3] His feast day is 21 August.

Saint Sidonius Apollinaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 430 Lugdunum, Gaul, Western Roman Empire |

| Died | c. 489 Kingdom of the Burgundians |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast | 21 August |

Life

Sidonius was born in Lugdunum (Lyon). His father (anonymous) was Prefect of Gaul under Valentinian III; he recalls with pride being present with his father at the installation of Astyrius as consul for the year 449.[4] Sidonius' grandfather was Praetorian Prefect of Gaul sometime prior to 409 and a friend of his successor Decimus Rusticus. Sidonius may be a descendant of another Apollinaris who was Prefect of Gaul under Constantine II between 337 and 340.

Sidonius married Papianilla, the daughter of Emperor Avitus, around 452.[5] This union produced one son, Apollinaris, and at least two daughters: Sidonius mentions in his letters Severina and Roscia, but a third, Alcima, is only mentioned much later by Gregory of Tours, and Theodor Mommsen has speculated that Alcima may be another name for one of his other daughters.[6] His known acquaintances include bishop Faustus of Riez and his theological adversary Claudianus Mamertus; his life and friendships put him in the center of 5th-century Roman affairs.

In 457 Majorian deprived Avitus of the empire and seized the city of Lyons; Sidonius fell into his hands. However, the reputation of Sidonius's learning led Majorian to treat him with the greatest respect. In return Sidonius composed a panegyric in his honour (as he had previously done for Avitus), which won for him a statue at Rome and the title of comes. In 467 or 468 the emperor Anthemius rewarded him for the panegyric which he had written in honour of him by raising him to the post of Urban Prefect of Rome, which he held until 469, and afterwards to the dignity of Patrician and Senator. In 470 or 472, he was elected to succeed Eparchius in the bishopric of Averna (Clermont).

When the Goths captured Clermont in 474 he was imprisoned, as he had taken an active part in its defense; but he was afterwards released from captivity by Euric, king of the Goths, and continued to shepherd his flock as he had done before; he did so until his death.

Sidonius's relations have been traced over several generations as a narrative of a family's fortunes, from the prominence of his paternal grandfather's time into later decline in the 6th century under the Franks. Sidonius's son Apollinaris, who was a correspondent of Ruricius of Limoges, commanded a unit raised in Auvergne on the losing side of the decisive Battle of Vouille, and also was bishop of Clermont for four months until he died.[7] Sidonius's grandson Arcadius, on hearing a rumor that the Frankish king Theuderic I had died, betrayed Clermont to Childebert I, only to abandon his wife and mother when Theuderic appeared; his other appearance in the history of Gregory of Tours is as a servant of king Childebert.[8]

Works

His extant works are his Panegyrics on different emperors (in which he draws largely upon Statius, Ausonius and Claudian), which document several important political events. Carmen 7 is a panegyric to his father-in-law Avitus on his inauguration as emperor. Carmen 5 is a panegyric to Majorian, which offers evidence that Sidonius was able to overcome the natural suspicion and hostility towards the man who was responsible for the death of his father-in-law. Carmen 2 is a panegyric to the emperor Anthemius, part of Sidonius' efforts to be appointed Urban Prefect of Rome; several samples of occasional verse; and nine books of Letters, about which W.B. Anderson notes, "Whatever one may think about their style and diction, the letters of Sidonius are an invaluable source of information on many aspects of the life of his time."[9] While very stilted in diction, these Letters reveal Sidonius as a man of genial temper, fond of good living and of pleasure. A letter of Sidonius's addressed to Riothamus, "King of the Brittones" (c. 470) is of particular interest, since it provides evidence that a king or military leader with ties to Britain lived around the time frame of King Arthur. The best edition is that in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Berlin, 1887), which gives a survey of the manuscripts. An English translation of his poetry and letters by W.B. Anderson, with accompanying Latin text, have been published by the Loeb Classical Library (volume 1, containing his poems and books 1-2 of his letters, 1939 [10]; remainder of letters, 1965). Among his lost works, is the one on Apollonius of Tyana.[11]

Gregory of Tours speaks of Sidonius as a man who could celebrate Mass from memory (without a sacramentary) and give unprepared speeches without any hesitation.[12]

Notes

- Apollinaris alludes to the date of his birthday in a short poem addressed to his brother-in-law Ecdicius, Carmen 20.

- The Fall of the Roman Empire Revisited: Sidonius Apollinaris and His Crisis of Identity Archived September 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Ralph W. Mathisen, "Epistolography, Literary Circles and Family Ties in Late Roman Gaul" Transactions of the American Philological Association 111 (1981), pp. 95-109.

- Epistulae, VIII.6.5; translated by W.B. Anderson, Sidonius: Poems and Letters (Harvard: Loeb Classical Library, 1965), vol. 2 p. 423

- Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, 2.21. This is confirmed by the otherwise oblique allusion in Sidonius' own Epistuale 2.2.3.

- Severina, Epistulae II.12.2; Roscia, Epistulae V.16.5; Alcima, Gregory of Tours Decem Libri Historiarum, III.2

- Gregory of Tours, 2.37, 3.2

- Gregory of Tours, 3.9, 11

- In his introduction to Sidonius: Poems and Letters (Cambridge: Loeb, 1939), vol. 1, p. lxiv.

- https://archive.org/details/L296SidoniusI12PoemsLetters

- http://www.gnosis.org/library/grs-mead/apollonius/apollonius_mead_04.htm

- Gregory of Tours, 2.22

Sources and further reading

- C.E. Stevens, Sidonius Apollinaris and his Age. Oxford: University Press, 1933.

- K.F. Stroheker. Der senatorische Adel im spätantiken Gallien. Tübingen, 1948.

- Nora Chadwick, Poetry and Letters in Early Christian Gaul London: Bowes and Bowes, 1955.

- Jill Harries (1994). Sidonius Apollinaris and the Fall of Rome, AD 407-485. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814472-4.

- Sigrid Mratschek, "Identitätsstiftung aus der Vergangenheit: Zum Diskurs über die trajanische Bildungskultur im Kreis des Sidonius Apollinaris", in Therese Fuhrer (hg), Die christlich-philosophischen Diskurse der Spätantike: Texte, Personen, Institutionen: Akten der Tagung vom 22.-25. Februar 2006 am Zentrum für Antike und Moderne der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2008) (Philosophie der Antike, 28),

- Johannes A. van Waarden and Gavin Kelly (eds), New Approaches to Sidonius Apollinaris, with Indices on Helga Köhler, C. Sollius Apollinaris Sidonius: Briefe Buch I. Leuven: Peeters, 2013.

- M. P. Hanaghan, Reading Sidonius' Epistles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Gavin Kelly and Joop van Waarden (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sidonius Apollinaris |

- Apollinaris Sidonius (5 November c.430 - 21 August c.483) – Medieval Lectures. Lynn Harry Nelson.

- Biographical introduction to the Letters, O. M. Dalton (1915)

- Complete English translation of the Letters of Sidonius Apollinaris, O. M. Dalton (1915)

- Sidonius Apollinaris, dedicated site, with bibliography and complete Latin text of the correspondence and the poetry, maintained by Joop van Waarden since 2003, frequently updated

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Latina with analytical indexes

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.