Roman Carthage

After the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of Carthage (Latin Carthāgō) was built on the same land. By the 3rd century, Carthage developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empire, with a population of several hundred thousand.[1] It was the center of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the empire. Carthage briefly became the capital of a usurper, Domitius Alexander, in 308–311. Conquered by the Vandals in 439,[2] Carthage served as the capital of the Vandal Kingdom for a century. Re-conquered into the Eastern Roman Empire in 533/4, it continued to serve as an Eastern Roman regional center, as the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa (after 590 the Exarchate of Carthage). The city was sacked and destroyed by Arabs after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire.[3] It remained occupied by a garrison during the Muslim period[4] and was used as a fort by the Muslims until the Hafsid period when it was taken by Crusaders with its defenders killed during the Eighth Crusade. The Hafsids decided to destroy its defenses so it couldn't be used as a base by a hostile power again.[5] Roman Carthage was used as a source to provide building materials for Kairouan and Tunis in the 8th century.[6]

Foundation

By 120 - 130 BC, Gaius Gracchus founded a short-lived colony, called Colonia Iunonia, after the Latin name for the Punic goddess Tanit, Iuno Caelestis. The purpose was to obtain arable lands for impoverished farmers. The Senate abolished the colony some time later to undermine Gracchus' power.

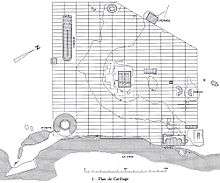

After this ill-fated attempt, a new city of Carthage was built on the same land by Julius Caesar in the period from 49 to 44 BC, and by the first century, it had grown to be the fourth largest city of the empire, with a population in excess of 100,000 people.[1] It was the center of the province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the Empire. Among its major monuments was an amphitheater, built in the 1st century, with a capacity of 30,000 seats.

Early Christianity

Carthage also became a center of early Christianity. Tertullian rhetorically addressed the Roman governor with the fact that the Christians of Carthage that just yesterday were few in number, now "have filled every place among you —cities, islands, fortresses, towns, market-places, the very camp, tribes, companies, palaces, senate, forum; we have left nothing to you but the temples of your gods." (Apologeticus written at Carthage, c. 197).

In the first of a string of rather poorly reported Councils at Carthage a few years later, no fewer than 70 bishops attended. Tertullian later broke with the mainstream that was represented more and more by the bishop of Rome, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, which Augustine of Hippo spent much time and parchment arguing against. In 397 at the Council of Carthage, the Biblical canon for the western Church was confirmed.

The Christians at Carthage conducted persecutions against the pagans, during which the pagan temples, sanctuaries and holy sites, notably the famous Temple of Juno Caelesti, were destroyed.[7]

Vandal period

The Vandals under their king Genseric crossed to Africa in 429,[8] either as a request of Bonifacius, a Roman general and the governor of the Diocese of Africa,[9] or as migrants in search of safety. They subsequently fought against the Roman forces there and by 435 had defeated the Roman forces in Africa and established the Vandal Kingdom. Genseric was considered a heretic, too, an Arian, and though Arians commonly despised Catholic Christians, a mere promise of toleration might have caused the city's population to accept him.

The Vandals during their conquest are said to have destroyed parts of Carthage by Victor Vitensis in Historia Persecutionis Africanae Provincia including various buildings and churches.[10]

Byzantine period

After two failed attempts(Majorian, Basiliscus) to recapture the city in the 5th century, the Empire finally subdued the Vandals in the Vandalic War of 533–534. Using Gaiseric's grandson's deposal by a distant cousin, Gelimer, as either a valid justification or pretext, the Romans dispatched an army to conquer the Vandal kingdom. On Sunday, October 15, 533, the Roman general Belisarius, accompanied by his wife Antonina, made his formal entry into Carthage, sparing it a sack and a massacre.

Thereafter, the city became the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa, which was made into an exarchate during the emperor Maurice's reign, as was Ravenna on the Italian Peninsula. These two exarchates were the western bulwarks of the Roman Empire, all that remained of its power in the West. In the early seventh century, the exarch of Carthage overthrew the Roman emperor, Phocas.

Islamic conquest

The Exarchate of Carthage was first assaulted by the Muslim expansion initiated from Egypt in 647, without lasting effect. A more protracted campaign lasted from 670 to 683. In 698, the Exarchate of Africa was finally overrun by Hassan Ibn al Numan and a force of 40,000 men.

Fearing that the Eastern Roman Empire might reconquer it, they decided to destroy Roman Carthage in a scorched earth policy and establish their headquarters somewhere else. Its walls were torn down, its water supply cut off, the agricultural land was ravaged and its harbors made unusable.[3]

The destruction of the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to Roman rule in the region since BCE 2nd century.

It is visible from archaeological evidence, that the town of Carthage continued to be occupied. The neighborhood of Bjordi Djedid continued to be occupied. The Baths of Antoninus continued to function in the Arab period and the historian Al-Bakri stated that they were still in good condition. They also had production centers nearby. It is difficult to determine whether the continued habitation of some other buildings belonged to Late Byzantine or Early Arab period. The Bir Ftouha church might have continued to remain in use though it is not clear when it became uninhabited.[4] Constantine the African was born in Carthage.[11]

The fortress of Carthage was used by the Muslims until Hafsid era and was captured by the Crusaders during the Eighth Crusade. After repulsing them, Muhammad I al-Mustansir decided to completely destroy Cathage's defenses to prevent a repeat.[5]

References

- Likely the fourth city in terms of population during the imperial period, following Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, in the 4th century also surpassed by Constantinople; also of comparable size were Ephesus, Smyrna and Pergamum. Stanley D. Brunn, Maureen Hays-Mitchell, Donald J. Zeigler (eds.), Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development, Rowman & Littlefield, 2012, p. 27

- p.402

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2008). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Brill Academic Press. p. 536. ISBN 978-9004153882.

- Anna Leone. Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. p. 179-186.

- Thomas F. Madden; James L. Naus; Vincent Ryan (eds.). Crusades – Medieval Worlds in Conflict. p. 113, 184.

- The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, Volume 1.

- Brent D. Shaw: Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine

- Collins, Roger (2000), "Vandal Africa, 429–533", XIV, Cambridge University Press, pp. 124

- Procopius Wars 3.5.23–24 in Collins 2004, p. 124

- Anna Leone. Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. p. 155.

- A Short History of Science to the Nineteenth Century.

- Raven, S. (2002), Rome in Africa, 3rd ed.

- Auguste Audollent, Carthage Romaine, 146 avant Jésus-Christ — 698 après Jésus-Christ, Paris (1901).

- Ernest Babelon, Carthage, Paris (1896).

See also

- History of Carthage

- Carthage (archaeological site)

- Baths of Antoninus

- Carthage National Museum

- Carthage Paleo-Christian Museum

- Bardo National Museum