Zaraï

Zaraï was a Berber, Carthaginian, and Roman town at the site of present-day Aïn Oulmene, Algeria. Under the Romans, it formed part of the province of Numidia.

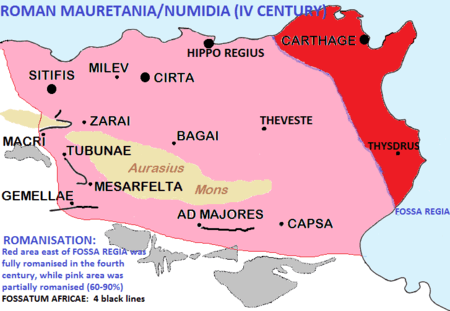

Zarai was near the Fossatum Africae, that marked the border between the Roman controlled Africa and the barbarian tribes. East of the Fossatum there was a partial Latinisation of the society | |

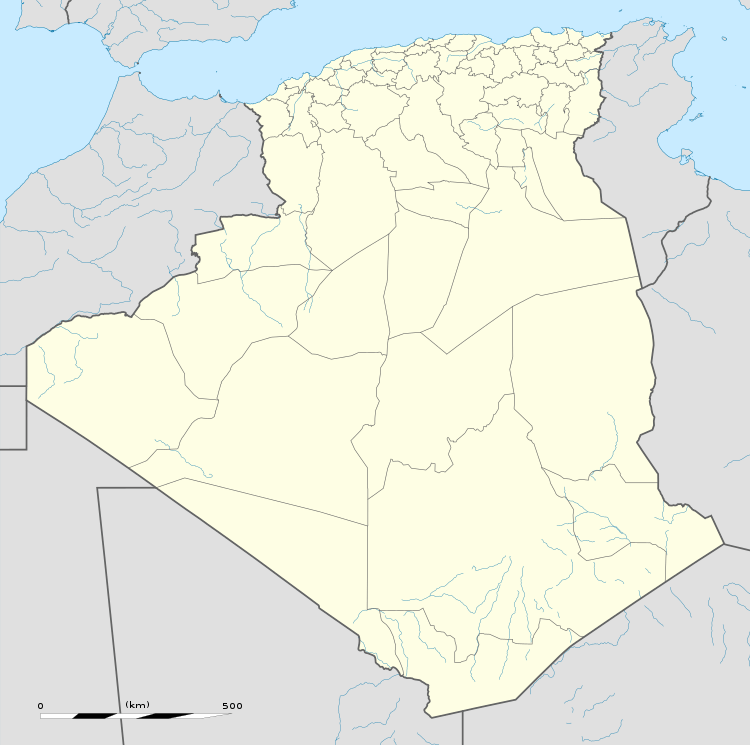

Shown within Algeria | |

| Location | Algeria |

|---|---|

| Region | Sétif Province |

| Coordinates | 35.800833°N 5.6775°E |

Name

The Punic name for the town was SRʾʿ (𐤎𐤓𐤀𐤏).[1]

Zarai is mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary[2] and in the Tabula Peutingeriana. Ptolemy calls it Zaratha[3] and wrongly places it in Mauretania Caesariensis. It is probably the Apuleius's Zaratha.[4] These two forms and the term "Zaraitani" found in an inscription[5] seem to indicate that the name Zaraï which appears on another inscription[6] must have lost a final letter.

Geography

The ruins of Zaraï are called "Henshir Zraïa" and are found inside the municipality of Ain Oulmene. They lie to the south-east of Setif in Algeria, crowning an eminence which overlooks all the country on the left bank of the Oued Taourlatent, known to the medieval Arabs as Oued Zaraoua.[7]

History

Zarai was protected after emperor Hadrian started the construction of a wall similar to the one with his name in Roman Britannia, by one of the sections of the Fossatum Africae: the Hodna or Bou Taleb section. This section begins near the north-east slopes of the Hodna Mountains, heads south following the foothills then east towards Zaraï, and doubles back westward to enclose the eastern end of the Hodna mountains, standing between them and the Roman settlements of Cellas and Macri. The length of this segment is about 100 km. It probably criss-crossed the ancient border between Numidia and Mauretania Sitifensis.

The frontier post stood at Zarai, the limit in this direction of the area for which the Third Augustan Legion was responsible. Zarai became a Roman town, of which considerable remains have survived. About 213 A.D. it ceased to be garrisoned, probably because the land round about had become peaceful, though it was still exposed to occasional raids from the desert. The district between Lambaesis and Zarai has preserved many traces of communities founded by veteran soldiers, who turned to agriculture after their service was over.... From Zarai two great routes ran into Mauretania, one proceeding in a north-westerly direction, and passing through the important city of Sitifis, the other taking a southerly line. Both roads met at Auzia (Aumale in Algeria). They ran through districts which were to a large extent occupied by estates of the emperors. -- James Reid

The Byzantines fortified the city as the western border town of their possessions in Africa. The small city of Zarai disappeared.

Ruins

Remains of a Byzantine citadel and of two Christian basilicas are still visible.[8]

Religion

Zarai was the seat of a Christian bishopric. It was one of the key cities of the Donatist controversy. The remains of a Byzantine citadel and of two basilicas are still visible.[7] Three bishops of Zaraï are known from antiquity. The see fell into abeyance after the Islamic conquest of the Maghreb but was later revived by the Roman Catholic Church as a titular see.

List of bishops

- Cresconius, present at the Conference of Carthage (411), where he had as a rival the Donatist Rogatus;[7]

- Adeodatus, one of the Catholic bishops whom Huneric summoned to a conference in Carthage in February 484 and then exiled.

- Edmond Alfred Dardel (23 Aug 1889 Appointed – 21 Mar 1890)

- Esteban Sánchez de las Heras (15 Jan 1895 Appointed – 21 Jun 1896)

- Jerome-Josse Van Aertselaer (7 May 1898 Appointed – 12 Jan 1924)

- Félix Bilbao y Ugarriza (23 Apr 1924 Appointed – 14 Dec 1925)

- Enrique María Dubuc Moreno (10 May 1926 Appointed – 26 Sep 1926)

- Jan Stavel (29 Apr 1927 Appointed – 6 Nov 1938)

- Vince Kovács (20 Jul 1940 Appointed – 15 Mar 1974)

- Benito Cocchi (12 Dec 1974 Appointed – 22 May 1982)

- José Sebastián Laboa Gallego (18 Dec 1982 Appointed – 24 Oct 2002)

- Assis Lopes (22 Jan 2003 Appointed – )

See also

References

Citations

- Head & al. (1911), p. 887.

- Ant. It., 35.

- Ptol., Geogr., IV. 2.

- Apuleius, Apologia, 23.

- Corp. Inscript. Lat. 4511.

- Corp. Inscript. 2532.

- Zarai at Catholic encyclopedia.org.

- "Zarai, on Catholic Encyclopaedia". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

Bibliography

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Zarai. |

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Numidia", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 884–887.

- Reid, James. The Municipalities of the Roman Empire. University of London. London, 1913 (reprint. ISBN 9781107683082)

- P. Trousset (2002). Les limites sud de la réoccupation Byzantine. Antiquité Tardive v. 10, p. 143–150.

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)