Adeni Jews

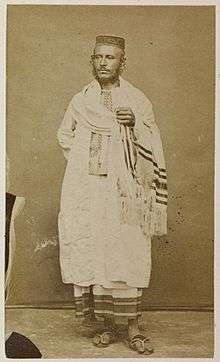

Adeni Jews (Hebrew: יהדות עדן), or Adenite Jews[1] are the historical Jewish community which resided in the port city of Aden.[2] Adenite culture became distinct from other Yemenite Jewish culture due to British control of the city and Indian-Iraqi influence as well as recent arrivals from Persia and Egypt.[3][4] Although they were separated, Adeni Jews depended on the greater Yemenite community for spiritual guidance, receiving their authorizations from Yemeni rabbis.[4] Virtually the entire population emigrated from Aden between June 1947 and September 1967.[5] As of 2004, there were 6,000 Adenites in Israel, and 1,500 in London.[6]

History

Early history

In 1489, Rabbi Obadiah di Bertinora encountered Jews in Jerusalem who had come from Aden, and who described for him their polity and settlement in the land of Yemen, as also knowledge about Moses' progeny who were settled some fifty-days' walking distance from their place as one journeys in the desert, and that they were encompassed by the river Sambation. He says that the Jews of Aden were only knowledgeable in the writings of Rabbi Alfasi and Maimonides, in the latter work of which they were especially well-versed.[7]

The Cairo Genizah (discovered in 1896) contains amazing letters from an earlier period of the sages which reveal connections between the Jewish communities of Egypt and Aden, and trade to India via Aden.[8] Some of the letters were sent by the heads of rabbinical academies to the Adeni and other communities seeking financial support for their institutions.

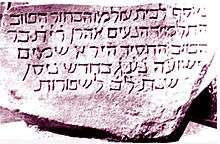

Digs at Beit She'arim in Israel provide proof that Jews were settled in Aden, Yemen during the mishnaic period (2nd and 3rd centuries CE). A hall was discovered there containing tombs of the Jews from Yemen. These Jews had been brought from Himyar for burial in the holy land. Tombstones were also found in Jewish cemeteries in Aden, dating as far back as the 12th century.

In the 10th century relations between the Jews of Yemen-Aden and of Babylonia became closer as evidenced by the adoption of upper pointing by the former, (sometimes called Babylonian pointing, in which the vocal marks are placed above instead of below the line as is the case today.) Although this did not last long, they retained this practice even after books began to be printed.

Adeni Jewry possessed Saadia Gaon's translations into Arabic of the Torah and the five megilloth. The prayers and liturgies composed by the Babylonian sages, such as the "Hosha'not" for Sukkoth, which is contained in Saadia Gaon's prayer book, were adopted by the Aden Jews and have been retained by them ever since. In one of the Cairo documents there appear instructions from Madmon Ben Yafter Ben Bendar, the ruler of Yemen and himself from Aden, to Halfon Ben Nethaniel Halevi from Fustat in Egypt, which indicates that already in the 10th century there was a small Jewish settlement in Aden.

From 1083–1173 Aden was ruled by an Arab dynasty called the Zura'ites. From this time onwards Aden served as an important community centre and became crucial as a port from the commercial sea lanes between the Mediterranean sea, India and further into the far east. The Jews became heavily involved in international trade and as a result they were able to support generously the yeshivoth of Babylonia, Egypt and the Land of Israel. From the 10th to the 13th centuries, Aden was the centre of Yemeni Jewish life. The "Yemeni governors" or the "ministers of the communities" sat in Aden and from there led the entire community, including Abu Ali Hasan in the late 11th century.[9] Their influence spread as far as Persia and Babylonia and throughout the Arabian Peninsula as far as the Hijaz in the north and Hadramout in the east.

Under the British Protectorate

The British Empire began to expand into the Middle East during the mid-19th century, and the Jews of Aden fared considerably better under the Aden Protectorate than under Muslim rule, which attracted Jewish immigrants from the rest of Yemen. After 1838, there were roughly 5,000 Jews in the city of Aden itself, and some 2,000 in the rest of what would become the Aden protectorate.

Adenite Diaspora

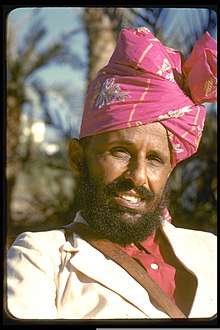

Jews from Aden established communities in Eritrea and Ethiopia. In 1935, sixty percent of Asmara's Jews were Adeni, while twenty percent were Yemeni.[4] Shoa Menahem Joseph, an Adeni Jew, was a leader of the Eritrean Jewish community from 1927 until his death in 1966.[4][10] Although the Adenim depended on them for religion, many Adenites wished to distance themselves from Yemeni Jews, worrying that associating with them would harm their status in Italian Eritrea's racial hierarchy.[3] As Adeni Jews were British subjects, they were considered members of the colonial group, while Yemeni Jews were considered indigenous subjects.[4] Attempts were made by Jewish leaders to equalize rights for all Eritrean Jews, however they were rejected by Italian authorities.[11]

A Yemeni Jew from Sana'a named Hubbara reported that when he first got to Asmara, a local Adeni refused to walk beside him as he did not want to seem too friendly with an indigenous black person. Hubbara elaborates:

- The Italians divided people into two groups: whites and blacks. The Europeans were white and the Abyssinians and other Africans were black. As for the Jews, those who dressed in European fashion were considered white, while those dressed in oriental clothing would be despised and humiliated just like the blacks.[4]

Addis Ababa at one point had a prominent Adenite community.[12] Most of them left fairly quickly, however some stayed and established synagogues and Hebrew schools.[4]

In 1986, there were six Adeni families left in the city, and almost all of their property was seized by the Mengistu regime.[13]

Synagogues of Aden

Before the last World War there were seven synagogues in Aden, and the Jewish population numbered several thousand.

In 1858 the Grand synagogue of Aden called the "Shield of Avraham" or "al-Milama'l-kabira" was built. It was large enough to house over 2000 worshippers.

A yeshiva called "Torah ve Hamitzvah" was also built next to the synagogue. The "Shulchan Aruch", Zohar, "Tikkun Hatzot", psalms, "the law of Israel" and "Ein Ya'akov" (composed by Ya'akov Havib) was studied at the yeshiva.

While the great synagogue was the hub of the Jewish community, several smaller synagogues also existed. Most notable among these were the al-Farhi synagogue, which house the highly venerated Al-Farhi Torah scroll and the synagogue of "Shemuel Nissim" which served as the Talmud Torah for boys until the early 1940s.

Another Synagogue was referred to as "Mi'lamat Hanokh". It was established in Aden by a man named Moshe Hanokh Halevi. He had emigrated to Aden and made his livelihood by the importation of sacred books from Europe.

On the eve of rosh Hashanah in 1924 a new synagogue named "Sukkat Shalom", popularly known as "Mialamat Silim", was inaugurated and celebrations continued into the night.[14]

Anti-Jewish riots in Aden

In May 1932, a riot began when Muslims accused Jews of throwing excrement into a mosque courtyard.[15] Sixty persons, including 25 Jews, were injured but there were no fatalities.[16] The Farhi synagogue was desecrated.[15]

Much more serious events occurred in December 1947, in the wake of the United Nations' approval of the Partition Plan for Palestine. On 2 December, a three-day strike was called to protest the decision.[17] Demonstrations led to stone and bottle throwing between Jews and Muslims in the Jewish quarter of Aden.[18] Jewish houses and shops were looted, and military control was declared when the crisis exceeded the capacity of the small police force.[18] The main military force available was the 1,800 strong Aden Protectorate Levies who were locally recruited soldiers with British and Arab officers.[18] Assistance was also received from several British warships, which sent landing parties, and the equivalent of two companies of British infantry flown in from the Canal Zone.[17] Order was not restored until 6 December.[18]

The main violence occurred in three locations. In Aden town (also called Crater), an attempt to impose a curfew was largely unsuccessful.[18] Jewish schools and houses were looted and set alight.[18] On the second day rifle fire began.[18] The Levies proved unreliable and worse; some fired indiscriminately and probably contributed to the casualties.[18] In the port towns of Steamer Point and Tawahi, most of the Jews were evacuated but some whose presence was not known to the police were killed.[18] Several Arabs who were apparently innocent were shot accidentally.[18] In the Arab town of Sheikh Othman, which had a large Jewish compound, a military contingent arrived to evacuate the 750 Jews to safety. However, several declined to leave and were later found dead.[18]

The official casualty count was 76–82 Jews (6 persons were unidentified) and 38 Arabs killed, and 76 Jews wounded.[18] At least 87 Arabs were known to have been wounded but many others failed to report their condition.[18] The dead included one Indian Medical Officer and one Levy.[18] More than 100 Jewish shops were looted and 30 houses burned.[18] An official enquiry conducted by Sir Harry Trusted determined that many individual Levies were sympathetic to the rioters and did not act to control them.[18] Nine Levies were imprisoned for looting.[18] Trusted put most of the blame on Yemeni "coolies", workers temporarily in the country who "have a low standard of life, are illiterate, fanatical and, when excited, may be savage."[18] He did not find claims of Jewish sniping to be convincing, though the Governor Sir Reginald Champion secretly reported to the British government that the two military fatalities were killed "almost certainly by Jewish sniper".[17] Jewish leaders acknowledged "many instances of Arabs and Indians sheltering and otherwise befriending their Jewish neighbours."[18] The British government was severely embarrassed by the riots, noting privately that they were urging the Arab states to protect their Jews when they themselves were unable to.[17]

Remnants of Jewish community destroyed

In March 2020, it was reported that the Jewish cemetery in Aden was destroyed.[19]

Writings

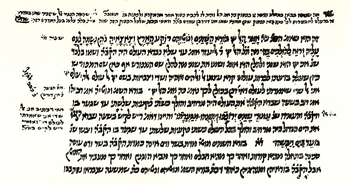

There never was a Hebrew printing press in Yemen, with the exception of Aden, and all the thousands of holy books used by the Jews there were handwritten.

The main Adeni synagogue in London was given the same name as the book Nahalat Yosef (1906). This book was written by Rabbi Shmuel Ben Yosef, grandson of the third dayan of the Aden rabbinical court Mori Yeshu'ah. This book covers all the religious practices of the Aden Jewish Community since the conclusions of the Jerusalem Talmud in the 5th century CE.

Midrash ha-Gadol written by David bar Amram al-Adani in the 13th century is a compilation of aggadic midrashim on the Pentateuch taken from the two Talmuds and earlier Midrashim. In addition, it borrows quotations from the Targums and Kabbalistic writings, and in this aspect is unique among the various midrashic collections.

See also

- Arab Jews

- Babylonian captivity

- Habbani Jews

- History of the Jews in Hadramaut

- History of the Jews in Saudi Arabia

- History of the Jews in the Arabian Peninsula

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Islamic–Jewish relations

- Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries

- List of Jews from the Arab world

- Mizrahi Jews

- Yemenite Jews

References

- Rosen-Koenigsbuch, Jacob (20 April 2018). "Resurrecting the Extinct Jewish Community of Port Said, Egypt". Haaretz.

- Sloam, Natalia (26 May 2015). "Passover traditions around the world". Fox.

- Dahlgren, Susanne (23 December 2010). Contesting Realities: The Public Sphere and Morality in Southern Yemen. Syracuse University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780815650935.

- Klorman, Bat-Zion (25 April 2014). Traditional Society in Transition: The Yemeni Jewish Experience. BRILL. pp. 72–86. ISBN 9789004272910.

- Ahroni, Reuben (1 June 1994). The Jews of the British Crown Colony of Aden. BRILL. pp. 28–31. ISBN 978-90-04-10110-4.

- "Jewish exile gets life". The Telegraph. 17 August 2004.

- Avraham Yari, Igros Eretz Yisroel (Letters of the Land of Israel), in the "Letter of Rabbi Obadiah di Bertinora from Jerusalem to his Brother," written in 1489, Tel-Aviv 1943, p. 140 (in PDF); See also Gedaliah ibn Jechia the Spaniard, Shalshelet Ha-Kabbalah, Venice 1585 (Hebrew), who testified in the name of Rabbi Obadiah di Bertinoro who had said that there came Jews in his days to Jerusalem, who had come from the southeastern hemisphere, along the sea of the [Indian] ocean, and who declared that they had no other book beside the Yad, belonging to Maimonides. Rabbi Yihya Saleh, speaking more distinctly about this episode, writes in his Questions & Responsa (Pe’ulath Sadiq, vol. ii, responsum 180) that he was referring there to the Jews of Yemen who had made a pilgrimage to the Land of Israel at that time.

- S.D. Goitein & M.A. Friedman, India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza ('India Book'). The Ben-Zvi Institute, Jerusalem & Brill, Leiden-Boston. xxix+918 pp. Bibliography, Indexes, 15 plates and 3 maps.

- "The Jewish Community of Aden". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- Tobi, Jacob (1994). West of Aden: A Survey of the Aden Jewish Community. p. 94.

- Greenfeld, Itzhak (1996). The History of the Jews of Aden and Yemen in Eritrea in the First Quarter of the Twentieth Century (Hebrew ed.). Te'uda. pp. 312–314.

- Amdur, Michael (1990). The Jewish Community in Aden 1900–1967 (Hebrew). pp. 24–32.

- Kapelyuk, Amnon (21 February 1986). "Why do you harass the Falashas? – Asked the Jews of Addis Ababa". Yedioth Ahronot: 7.

- Reuben Ahroni (1994). The Jews of the British Crown Colony of Aden: History, Culture, and Ethnic Relations. Leiden: BRILL. p. 113. ISBN 90-04-10110-1.

- Tudor Parfitt (1996). The Road to Redemption—The Jews of the Yemen 1900–1950. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 128–129.

- Secretary of State for India, House of Commons debates of May 30, 1932 and June 1, 1932. However, John Willis (1997). "Colonial Policing in Aden, 1937–1967". The Arab Studies Journal. 5 (1): 57–91. says there was one fatality.

- Tudor Parfitt (1996). The Road to Redemption—The Jews of the Yemen 1900–1950. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 165–168.

- Harry Trusted (1948). Report of the Commission of Enquiry into Disturbances in Aden, December 1947. Colonial No. 233. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

- See "Killing Jewish Dead...By Dr Cohan". Begin-Sadat Peace Ceneter. Retrieved 6 July 2020..