Landslide

The term landslide or less frequently, landslip,[1] refers to several forms of mass wasting that include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of environments, characterized by either steep or gentle slope gradients, from mountain ranges to coastal cliffs or even underwater, in which case they are called submarine landslides. Gravity is the primary driving force for a landslide to occur, but there are other factors affecting slope stability that produce specific conditions that make a slope prone to failure. In many cases, the landslide is triggered by a specific event (such as a heavy rainfall, an earthquake, a slope cut to build a road, and many others), although this is not always identifiable.

Causes

Landslides occur when the slope (or a portion of it) undergoes some processes that change its condition from stable to unstable. This is essentially due to a decrease in the shear strength of the slope material, to an increase in the shear stress borne by the material, or to a combination of the two. A change in the stability of a slope can be caused by a number of factors, acting together or alone. Natural causes of landslides include:

- saturation by rain water infiltration, snow melting, or glaciers melting;

- rising of groundwater or increase of pore water pressure (e.g. due to aquifer recharge in rainy seasons, or by rain water infiltration);[2]

- increase of hydrostatic pressure in cracks and fractures;[2][3]

- loss or absence of vertical vegetative structure, soil nutrients, and soil structure (e.g. after a wildfire – a fire in forests lasting for 3–4 days);

- erosion of the toe of a slope by rivers or ocean waves;

- physical and chemical weathering (e.g. by repeated freezing and thawing, heating and cooling, salt leaking in the groundwater or mineral dissolution);[4][5]

- ground shaking caused by earthquakes, which can destabilize the slope directly (e.g., by inducing soil liquefaction) or weaken the material and cause cracks that will eventually produce a landslide;[3][6][7]

- volcanic eruptions;

Landslides are aggravated by human activities, such as:

- deforestation, cultivation and construction;

- vibrations from machinery or traffic;

- blasting and mining;[8]

- earthwork (e.g. by altering the shape of a slope, or imposing new loads);

- in shallow soils, the removal of deep-rooted vegetation that binds colluvium to bedrock;

- agricultural or forestry activities (logging), and urbanization, which change the amount of water infiltrating the soil.

_1950%2C_2.jpg)

Types

Debris flow

Slope material that becomes saturated with water may develop into a debris flow or mud flow. The resulting slurry of rock and mud may pick up trees, houses and cars, thus blocking bridges and tributaries causing flooding along its path.

Debris flow is often mistaken for flash flood, but they are entirely different processes.

Muddy-debris flows in alpine areas cause severe damage to structures and infrastructure and often claim human lives. Muddy-debris flows can start as a result of slope-related factors and shallow landslides can dam stream beds, resulting in temporary water blockage. As the impoundments fail, a "domino effect" may be created, with a remarkable growth in the volume of the flowing mass, which takes up the debris in the stream channel. The solid–liquid mixture can reach densities of up to 2,000 kg/m3 (120 lb/cu ft) and velocities of up to 14 m/s (46 ft/s).[9][10] These processes normally cause the first severe road interruptions, due not only to deposits accumulated on the road (from several cubic metres to hundreds of cubic metres), but in some cases to the complete removal of bridges or roadways or railways crossing the stream channel. Damage usually derives from a common underestimation of mud-debris flows: in the alpine valleys, for example, bridges are frequently destroyed by the impact force of the flow because their span is usually calculated only for a water discharge. For a small basin in the Italian Alps (area 1.76 km2 (0.68 sq mi)) affected by a debris flow,[9] estimated a peak discharge of 750 m3/s (26,000 cu ft/s) for a section located in the middle stretch of the main channel. At the same cross section, the maximum foreseeable water discharge (by HEC-1), was 19 m3/s (670 cu ft/s), a value about 40 times lower than that calculated for the debris flow that occurred.

Earthflow

An earthflow is the downslope movement of mostly fine-grained material. Earthflows can move at speeds within a very wide range, from as low as 1 mm/yr (0.039 in/yr)[4][5] to 20 km/h (12.4 mph). Though these are a lot like mudflows, overall they are more slow moving and are covered with solid material carried along by flow from within. They are different from fluid flows which are more rapid. Clay, fine sand and silt, and fine-grained, pyroclastic material are all susceptible to earthflows. The velocity of the earthflow is all dependent on how much water content is in the flow itself: the higher the water content in the flow, the higher the velocity will be.

These flows usually begin when the pore pressures in a fine-grained mass increase until enough of the weight of the material is supported by pore water to significantly decrease the internal shearing strength of the material. This thereby creates a bulging lobe which advances with a slow, rolling motion. As these lobes spread out, drainage of the mass increases and the margins dry out, thereby lowering the overall velocity of the flow. This process causes the flow to thicken. The bulbous variety of earthflows are not that spectacular, but they are much more common than their rapid counterparts. They develop a sag at their heads and are usually derived from the slumping at the source.

Earthflows occur much more during periods of high precipitation, which saturates the ground and adds water to the slope content. Fissures develop during the movement of clay-like material which creates the intrusion of water into the earthflows. Water then increases the pore-water pressure and reduces the shearing strength of the material.[11]

Debris slide

A debris slide is a type of slide characterized by the chaotic movement of rocks, soil, and debris mixed with water and/or ice. They are usually triggered by the saturation of thickly vegetated slopes which results in an incoherent mixture of broken timber, smaller vegetation and other debris.[11] Debris avalanches differ from debris slides because their movement is much more rapid. This is usually a result of lower cohesion or higher water content and commonly steeper slopes.

Steep coastal cliffs can be caused by catastrophic debris avalanches. These have been common on the submerged flanks of ocean island volcanos such as the Hawaiian Islands and the Cape Verde Islands.[12] Another slip of this type was Storegga landslide.

Debris slides generally start with big rocks that start at the top of the slide and begin to break apart as they slide towards the bottom. This is much slower than a debris avalanche. Debris avalanches are very fast and the entire mass seems to liquefy as it slides down the slope. This is caused by a combination of saturated material, and steep slopes. As the debris moves down the slope it generally follows stream channels leaving a v-shaped scar as it moves down the hill. This differs from the more U-shaped scar of a slump. Debris avalanches can also travel well past the foot of the slope due to their tremendous speed.[13]

Rock avalanche

A rock avalanche, sometimes referred to as sturzstrom, is a type of large and fast-moving landslide. It is rarer than other types of landslides and therefore poorly understood. It exhibits typically a long run-out, flowing very far over a low angle, flat, or even slightly uphill terrain. The mechanisms favoring the long runout can be different, but they typically result in the weakening of the sliding mass as the speed increases.[14][15][16]

Shallow landslide

A landslide in which the sliding surface is located within the soil mantle or weathered bedrock (typically to a depth from few decimeters to some meters) is called a shallow landslide. They usually include debris slides, debris flow, and failures of road cut-slopes. Landslides occurring as single large blocks of rock moving slowly down slope are sometimes called block glides.

Shallow landslides can often happen in areas that have slopes with high permeable soils on top of low permeable bottom soils. The low permeable, bottom soils trap the water in the shallower, high permeable soils creating high water pressure in the top soils. As the top soils are filled with water and become heavy, slopes can become very unstable and slide over the low permeable bottom soils. Say there is a slope with silt and sand as its top soil and bedrock as its bottom soil. During an intense rainstorm, the bedrock will keep the rain trapped in the top soils of silt and sand. As the topsoil becomes saturated and heavy, it can start to slide over the bedrock and become a shallow landslide. R. H. Campbell did a study on shallow landslides on Santa Cruz Island, California. He notes that if permeability decreases with depth, a perched water table may develop in soils at intense precipitation. When pore water pressures are sufficient to reduce effective normal stress to a critical level, failure occurs.[17]

Deep-seated landslide

Deep-seated landslides are those in which the sliding surface is mostly deeply located below the maximum rooting depth of trees (typically to depths greater than ten meters). They usually involve deep regolith, weathered rock, and/or bedrock and include large slope failure associated with translational, rotational, or complex movement. This type of landslide potentially occurs in an tectonic active region like Zagros Mountain in Iran. These typically move slowly, only several meters per year, but occasionally move faster. They tend to be larger than shallow landslides and form along a plane of weakness such as a fault or bedding plane. They can be visually identified by concave scarps at the top and steep areas at the toe.[18]

Causing tsunamis

Landslides that occur undersea, or have impact into water e.g. significant rockfall or volcanic collapse into the sea,[19] can generate tsunamis. Massive landslides can also generate megatsunamis, which are usually hundreds of meters high. In 1958, one such tsunami occurred in Lituya Bay in Alaska.[12][20]

Related phenomena

- An avalanche, similar in mechanism to a landslide, involves a large amount of ice, snow and rock falling quickly down the side of a mountain.

- A pyroclastic flow is caused by a collapsing cloud of hot ash, gas and rocks from a volcanic explosion that moves rapidly down an erupting volcano.

Landslide prediction mapping

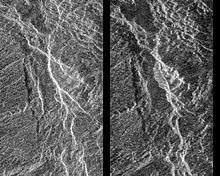

Landslide hazard analysis and mapping can provide useful information for catastrophic loss reduction, and assist in the development of guidelines for sustainable land-use planning. The analysis is used to identify the factors that are related to landslides, estimate the relative contribution of factors causing slope failures, establish a relation between the factors and landslides, and to predict the landslide hazard in the future based on such a relationship.[21] The factors that have been used for landslide hazard analysis can usually be grouped into geomorphology, geology, land use/land cover, and hydrogeology. Since many factors are considered for landslide hazard mapping, GIS is an appropriate tool because it has functions of collection, storage, manipulation, display, and analysis of large amounts of spatially referenced data which can be handled fast and effectively.[22] Cardenas reported evidence on the exhaustive use of GIS in conjunction of uncertainty modelling tools for landslide mapping.[23][24] Remote sensing techniques are also highly employed for landslide hazard assessment and analysis. Before and after aerial photographs and satellite imagery are used to gather landslide characteristics, like distribution and classification, and factors like slope, lithology, and land use/land cover to be used to help predict future events.[25] Before and after imagery also helps to reveal how the landscape changed after an event, what may have triggered the landslide, and shows the process of regeneration and recovery.[26]

Using satellite imagery in combination with GIS and on-the-ground studies, it is possible to generate maps of likely occurrences of future landslides.[27] Such maps should show the locations of previous events as well as clearly indicate the probable locations of future events. In general, to predict landslides, one must assume that their occurrence is determined by certain geologic factors, and that future landslides will occur under the same conditions as past events.[28] Therefore, it is necessary to establish a relationship between the geomorphologic conditions in which the past events took place and the expected future conditions.[29]

Natural disasters are a dramatic example of people living in conflict with the environment. Early predictions and warnings are essential for the reduction of property damage and loss of life. Because landslides occur frequently and can represent some of the most destructive forces on earth, it is imperative to have a good understanding as to what causes them and how people can either help prevent them from occurring or simply avoid them when they do occur. Sustainable land management and development is also an essential key to reducing the negative impacts felt by landslides.

GIS offers a superior method for landslide analysis because it allows one to capture, store, manipulate, analyze, and display large amounts of data quickly and effectively. Because so many variables are involved, it is important to be able to overlay the many layers of data to develop a full and accurate portrayal of what is taking place on the Earth's surface. Researchers need to know which variables are the most important factors that trigger landslides in any given location. Using GIS, extremely detailed maps can be generated to show past events and likely future events which have the potential to save lives, property, and money.

Global landslide risks

Global landslide risks Ferguson Slide on California State Route 140 in June 2006

Ferguson Slide on California State Route 140 in June 2006 Trackside rock slide detector on the UPRR Sierra grade near Colfax, CA

Trackside rock slide detector on the UPRR Sierra grade near Colfax, CA

Prehistoric landslides

- Storegga Slide, some 8,000 years ago off the western coast of Norway. Caused massive tsunamis in Doggerland and other countries connected to the North Sea. A total volume of 3,500 km3 (840 cu mi) debris was involved; comparable to a 34 m (112 ft) thick area the size of Iceland. The landslide is thought to be among the largest in history.

- Landslide which moved Heart Mountain to its current location, the largest continental landslide discovered so far. In the 48 million years since the slide occurred, erosion has removed most of the portion of the slide.

- Flims Rockslide, ca. 12 km3 (2.9 cu mi), Switzerland, some 10000 years ago in post-glacial Pleistocene/Holocene, the largest so far described in the alps and on dry land that can be easily identified in a modestly eroded state.[31]

- The landslide around 200 BC which formed Lake Waikaremoana on the North Island of New Zealand, where a large block of the Ngamoko Range slid and dammed a gorge of Waikaretaheke River, forming a natural reservoir up to 256 metres (840 ft) deep.

- Cheekye Fan, British Columbia, Canada, ca. 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi), Late Pleistocene in age.

- The Manang-Braga rock avalanche/debris flow may have formed Marsyangdi Valley in the Annapurna Region, Nepal, during an interstadial period belonging to the last glacial period.[32] Over 15 km3 of material are estimated to have been moved in the single event, making it one of the largest continental landslides.

- A massive slope failure 60 km north of Kathmandu Nepal, involving an estimated 10–15 km3.[33] Prior to this landslide the mountain may have been the world's 15th mountain above 8000m.

Historical landslides

- The 1806 Goldau landslide on September 2, 1806

- The Cap Diamant Québec rockslide on September 19, 1889

- Frank Slide, Turtle Mountain, Alberta, Canada, on 29 April 1903

- Khait landslide, Khait, Tajikistan, Soviet Union, on July 10, 1949

- Monte Toc landslide (260 million cubic metres, 9.2 billion cubic feet) falling into the Vajont Dam basin in Italy, causing a megatsunami and about 2000 deaths, on October 9, 1963

- Hope Slide landslide (46 million cubic metres, 1.6 billion cubic feet) near Hope, British Columbia on January 9, 1965.[34]

- The 1966 Aberfan disaster

- Tuve landslide in Gothenburg, Sweden on November 30, 1977.

- The 1979 Abbotsford landslip, Dunedin, New Zealand on August 8, 1979.

- Val Pola landslide during Valtellina disaster (1987) Italy

- Thredbo landslide, Australia on 30 July 1997, destroyed hostel.

- Vargas mudslides, due to heavy rains in Vargas State, Venezuela, in December, 1999, causing tens of thousands of deaths.

- 2005 La Conchita landslide in Ventura, California causing 10 deaths.

- 2007 Chittagong mudslide, in Chittagong, Bangladesh, on June 11, 2007.

- 2008 Cairo landslide on September 6, 2008.

- The 2009 Peloritani Mountains disaster caused 37 deaths, on October 1.[35]

- The 2010 Uganda landslide caused over 100 deaths following heavy rain in Bududa region.

- Zhouqu county mudslide in Gansu, China on August 8, 2010.[36]

- Devil's Slide, an ongoing landslide in San Mateo County, California

- 2011 Rio de Janeiro landslide in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on January 11, 2011, causing 610 deaths.[37]

- 2014 Pune landslide, in Pune, India.

- 2014 Oso mudslide, in Oso, Washington

- 2017 Mocoa landslide, in Mocoa, Colombia

Extraterrestrial landslides

Evidence of past landslides has been detected on many bodies in the solar system, but since most observations are made by probes that only observe for a limited time and most bodies in the solar system appear to be geologically inactive not many landslides are known to have happened in recent times. Both Venus and Mars have been subject to long-term mapping by orbiting satellites, and examples of landslides have been observed on both planets.

Landslide mitigation

See also

References

- "Landslide synonyms". www.thesaurus.com. Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus. 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Hu, Wei; Scaringi, Gianvito; Xu, Qiang; Van Asch, Theo W. J. (2018-04-10). "Suction and rate-dependent behaviour of a shear-zone soil from a landslide in a gently-inclined mudstone-sandstone sequence in the Sichuan basin, China". Engineering Geology. 237: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2018.02.005. ISSN 0013-7952.

- Fan, Xuanmei; Xu, Qiang; Scaringi, Gianvito (2017-12-01). "Failure mechanism and kinematics of the deadly June 24th 2017 Xinmo landslide, Maoxian, Sichuan, China". Landslides. 14 (6): 2129–2146. doi:10.1007/s10346-017-0907-7. ISSN 1612-5118.

- Di Maio, Caterina; Vassallo, Roberto; Scaringi, Gianvito; De Rosa, Jacopo; Pontolillo, Dario Michele; Maria Grimaldi, Giuseppe (2017-11-01). "Monitoring and analysis of an earthflow in tectonized clay shales and study of a remedial intervention by KCl wells". Rivista Italiana di Geotecnica. 51 (3): 48–63. doi:10.19199/2017.3.0557-1405.048.

- Di Maio, Caterina; Scaringi, Gianvito; Vassallo, R (2014-01-01). "Residual strength and creep behaviour on the slip surface of specimens of a landslide in marine origin clay shales: influence of pore fluid composition". Landslides. 12 (4): 657–667. doi:10.1007/s10346-014-0511-z.

- Fan, Xuanmei; Scaringi, Gianvito; Domènech, Guillem; Yang, Fan; Guo, Xiaojun; Dai, Lanxin; He, Chaoyang; Xu, Qiang; Huang, Runqiu (2019-01-09). "Two multi-temporal datasets that track the enhanced landsliding after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake". Earth System Science Data. 11 (1): 35–55. Bibcode:2019ESSD...11...35F. doi:10.5194/essd-11-35-2019. ISSN 1866-3508.

- Fan, Xuanmei; Xu, Qiang; Scaringi, Gianvito (2018-01-26). "Brief communication: Post-seismic landslides, the tough lesson of a catastrophe". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 18 (1): 397–403. Bibcode:2018NHESS..18..397F. doi:10.5194/nhess-18-397-2018. ISSN 1561-8633.

- Fan, Xuanmei; Xu, Qiang; Scaringi, Gianvito (2018-10-24). "The "long" runout rock avalanche in Pusa, China, on August 28, 2017: a preliminary report". Landslides. 16: 139–154. doi:10.1007/s10346-018-1084-z. ISSN 1612-5118.

- Chiarle, Marta; Luino, Fabio (1998). "Colate detritiche torrentizie sul Monte Mottarone innescate dal nubifragio dell'8 luglio 1996". La prevenzione delle catastrofi idrogeologiche. Il contributo della ricerca scientifica (conference book). pp. 231–245.

- Arattano, Massimo (2003). "Monitoring the presence of the debris flow front and its velocity through ground vibration detectors". Third International Conference on Debris-flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction, and Assessment (debris flow): 719–730.

- Easterbrook, Don J. (1999). Surface Processes and Landforms. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-860958-0.

- Le Bas, T.P. (2007), "Slope Failures on the Flanks of Southern Cape Verde Islands", in Lykousis, Vasilios (ed.), Submarine mass movements and their consequences: 3rd international symposium, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-6511-8

- Schuster, R.L. & Krizek, R.J. (1978). Landslides: Analysis and Control. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences.

- Hu, Wei; Scaringi, Gianvito; Xu, Qiang; Huang, Runqiu (2018-06-05). "Internal erosion controls failure and runout of loose granular deposits: Evidence from flume tests and implications for post-seismic slope healing". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (11): 5518. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.5518H. doi:10.1029/2018GL078030.

- Hu, Wei; Xu, Qiang; Wang, Gonghui; Scaringi, Gianvito; McSaveney, Mauri; Hicher, Pierre-Yves (2017-10-31). "Shear Resistance Variations in Experimentally Sheared Mudstone Granules: A Possible Shear-Thinning and Thixotropic Mechanism". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (21): 11, 040. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..4411040H. doi:10.1002/2017GL075261.

- Scaringi, Gianvito; Hu, Wei; Xu, Qiang; Huang, Runqiu (2017-12-20). "Shear-Rate-Dependent Behavior of Clayey Bimaterial Interfaces at Landslide Stress Levels". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (2): 766. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45..766S. doi:10.1002/2017GL076214.

- Renwick, W.; Brumbaugh, R.; Loeher, L (1982). "Landslide Morphology and Processes on Santa Cruz Island California". Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Physical Geography. 64 (3/4): 149–159. doi:10.2307/520642. JSTOR 520642.

- Johnson, B.F. (June 2010). "Slippery slopes". Earth magazine. pp. 48–55.

- "Ancient Volcano Collapse Caused A Tsunami With An 800-Foot Wave". Popular Science. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- Mitchell, N (2003). "Susceptibility of mid-ocean ridge volcanic islands and seamounts to large scale landsliding". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (B8): 1–23. Bibcode:2003JGRB..108.2397M. doi:10.1029/2002jb001997.

- Chen, Zhaohua; Wang, Jinfei (2007). "Landslide hazard mapping using logistic regression model in Mackenzie Valley, Canada". Natural Hazards. 42: 75–89. doi:10.1007/s11069-006-9061-6.

- Clerici, A; Perego, S; Tellini, C; Vescovi, P (2002). "A procedure for landslide susceptibility zonation by the conditional analysis method1". Geomorphology. 48 (4): 349–364. Bibcode:2002Geomo..48..349C. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00079-X.

- Cardenas, IC (2008). "Landslide susceptibility assessment using Fuzzy Sets, Possibility Theory and Theory of Evidence. Estimación de la susceptibilidad ante deslizamientos: aplicación de conjuntos difusos y las teorías de la posibilidad y de la evidencia". Ingenieria e Investigación. 28 (1).

- Cardenas, IC (2008). "Non-parametric modeling of rainfall in Manizales City (Colombia) using multinomial probability and imprecise probabilities. Modelación no paramétrica de lluvias para la ciudad de Manizales, Colombia: una aplicación de modelos multinomiales de probabilidad y de probabilidades imprecisas". Ingenieria e Investigación. 28 (2).

- Metternicht, G; Hurni, L; Gogu, R (2005). "Remote sensing of landslides: An analysis of the potential contribution to geo-spatial systems for hazard assessment in mountainous environments". Remote Sensing of Environment. 98 (2–3): 284–303. Bibcode:2005RSEnv..98..284M. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2005.08.004.

- De La Ville, Noemi; Chumaceiro Diaz, Alejandro; Ramirez, Denisse (2002). "Remote Sensing and GIS Technologies as Tools to Support Sustainable Management of Areas Devastated by Landslides" (PDF). Environment, Development and Sustainability. 4 (2): 221–229. doi:10.1023/A:1020835932757.

- Fabbri, Andrea G.; Chung, Chang-Jo F.; Cendrero, Antonio; Remondo, Juan (2003). "Is Prediction of Future Landslides Possible with a GIS?". Natural Hazards. 30 (3): 487–503. doi:10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000007282.62071.75.

- Lee, S; Talib, Jasmi Abdul (2005). "Probabilistic landslide susceptibility and factor effect analysis". Environmental Geology. 47 (7): 982–990. doi:10.1007/s00254-005-1228-z.

- Ohlmacher, G (2003). "Using multiple logistic regression and GIS technology to predict landslide hazard in northeast Kansas, USA". Engineering Geology. 69 (3–4): 331–343. doi:10.1016/S0013-7952(03)00069-3.

- Rose & Hunger, "Forecasting potential slope failure in open pit mines", Journal of Rock Mechanics & Mining Sciences, February 17, 2006. August 20, 2015.

- Weitere Erkenntnisse und weitere Fragen zum Flimser Bergsturz Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine A.v. Poschinger, Angewandte Geologie, Vol. 11/2, 2006

- Fort, Monique (2011). "Two large late quaternary rock slope failures and their geomorphic significance, Annapurna, Himalayas (Nepal)". Geografia Fisica e Dinamica Quaternaria. 34: 5–16.

- Weidinger, Johannes T.; Schramm, Josef-Michael; Nuschej, Friedrich (2002-12-30). "Ore mineralization causing slope failure in a high-altitude mountain crest—on the collapse of an 8000 m peak in Nepal". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 21 (3): 295–306. Bibcode:2002JAESc..21..295W. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00080-9.

- "Hope Slide". BC Geographical Names.

- Peres, D. J.; Cancelliere, A. (2016-10-01). "Estimating return period of landslide triggering by Monte Carlo simulation". Journal of Hydrology. Flash floods, hydro-geomorphic response and risk management. 541: 256–271. Bibcode:2016JHyd..541..256P. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.03.036.

- "Large landslide in Gansu Zhouqu August 7". Easyseosolution.com. August 19, 2010. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010.

- "Brazil mudslide death toll passes 450". Cbc.ca. January 13, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Landslide. |